Diversify revenue streams; Build a loyal community; Collaborate with artists and

galleries; Offer advertising and sponsorship packages; Explore digital opportunities,

Seek grants and sponsorships, Establish strategic partnerships, Monitor and adapt.

–ChatGPT when asked how one should start an art magazine

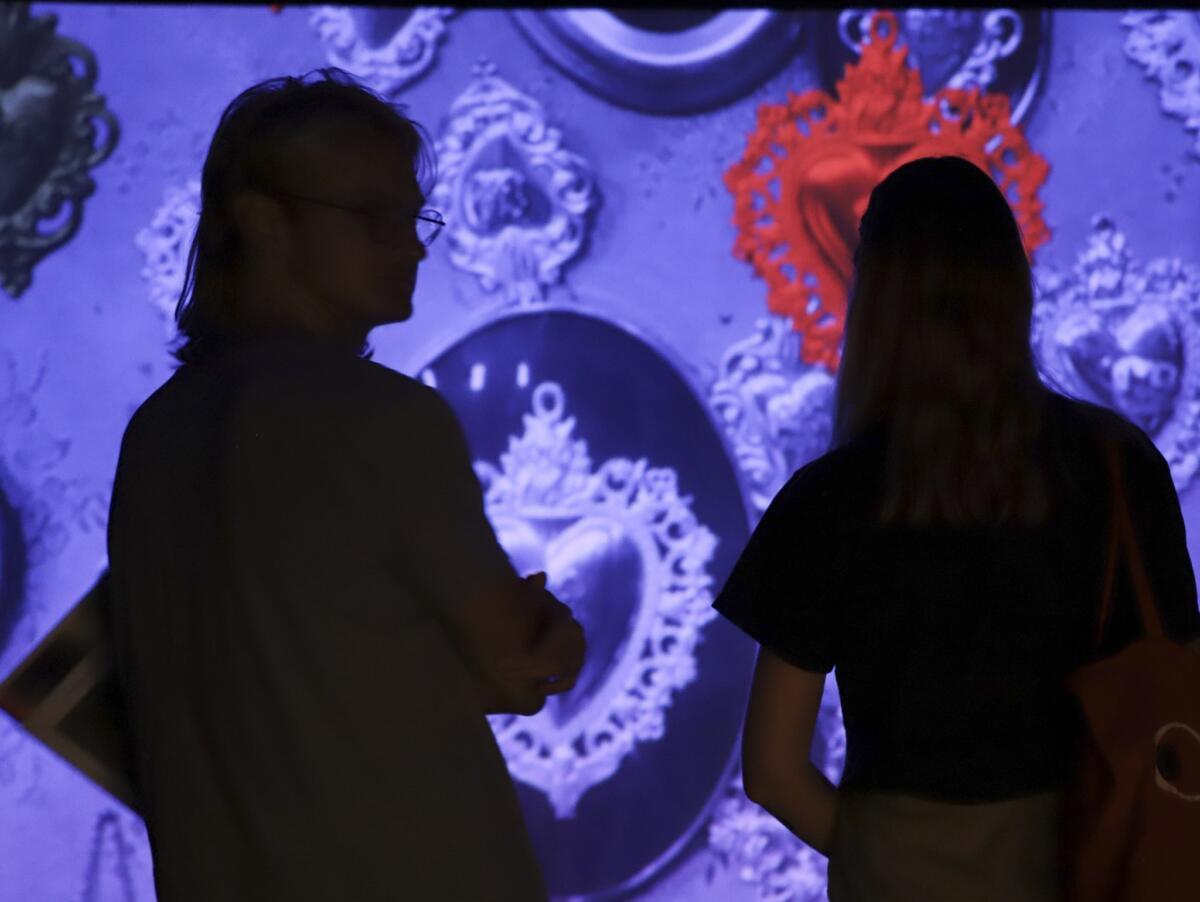

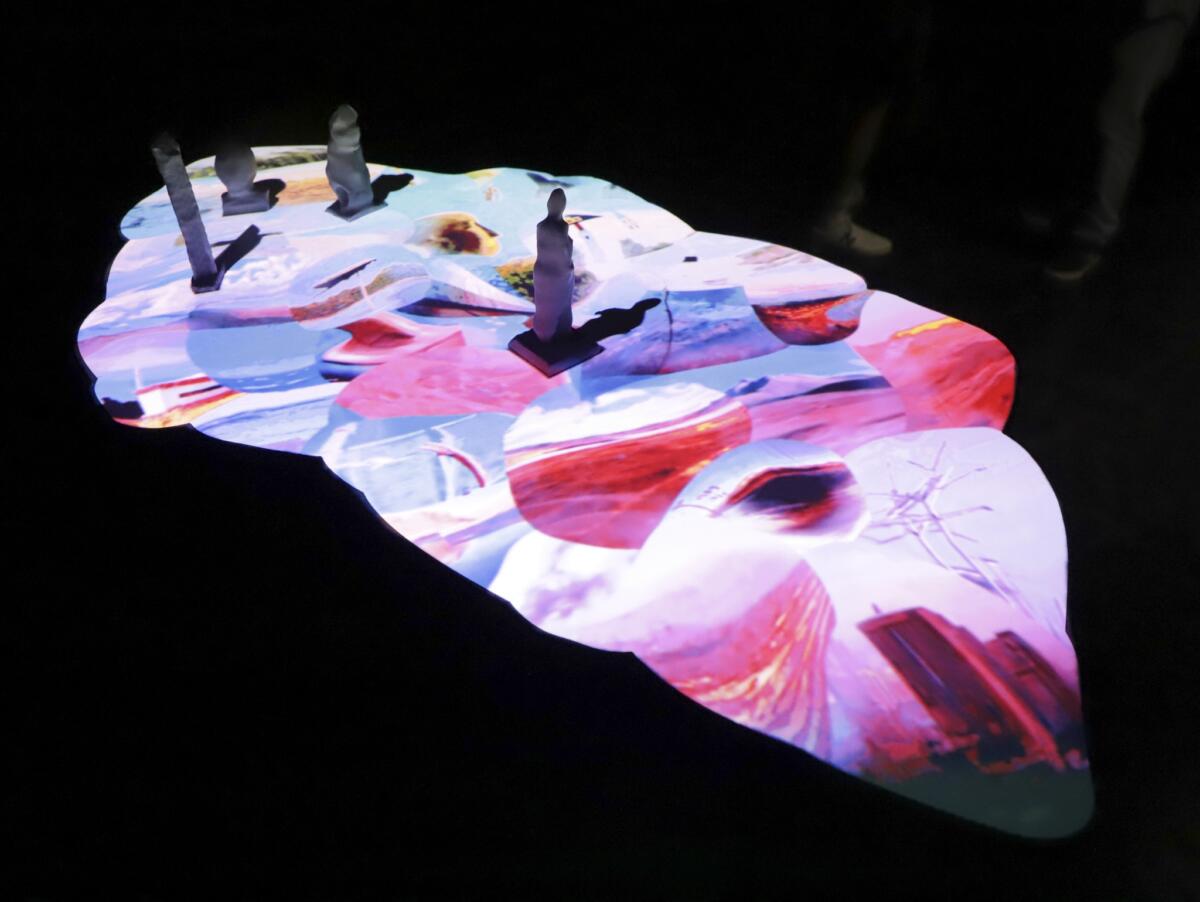

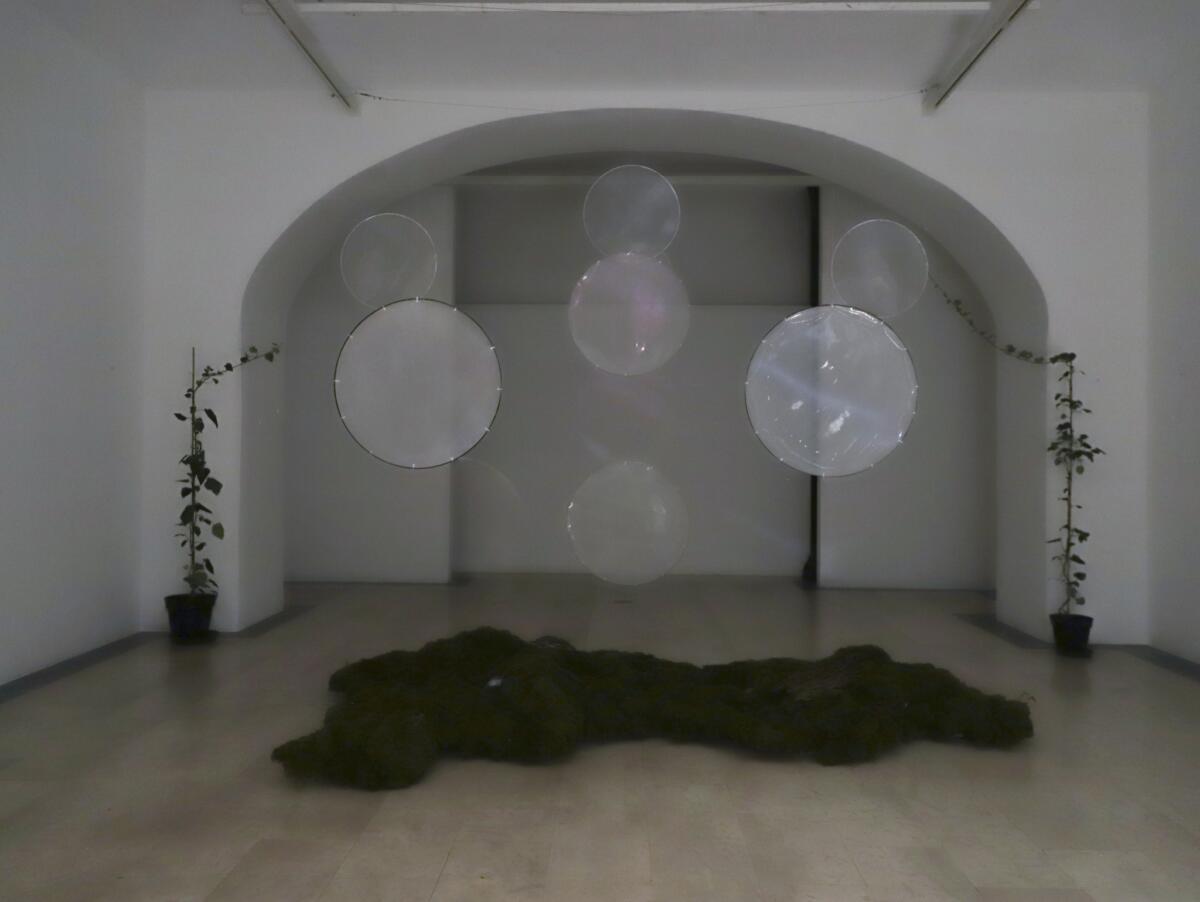

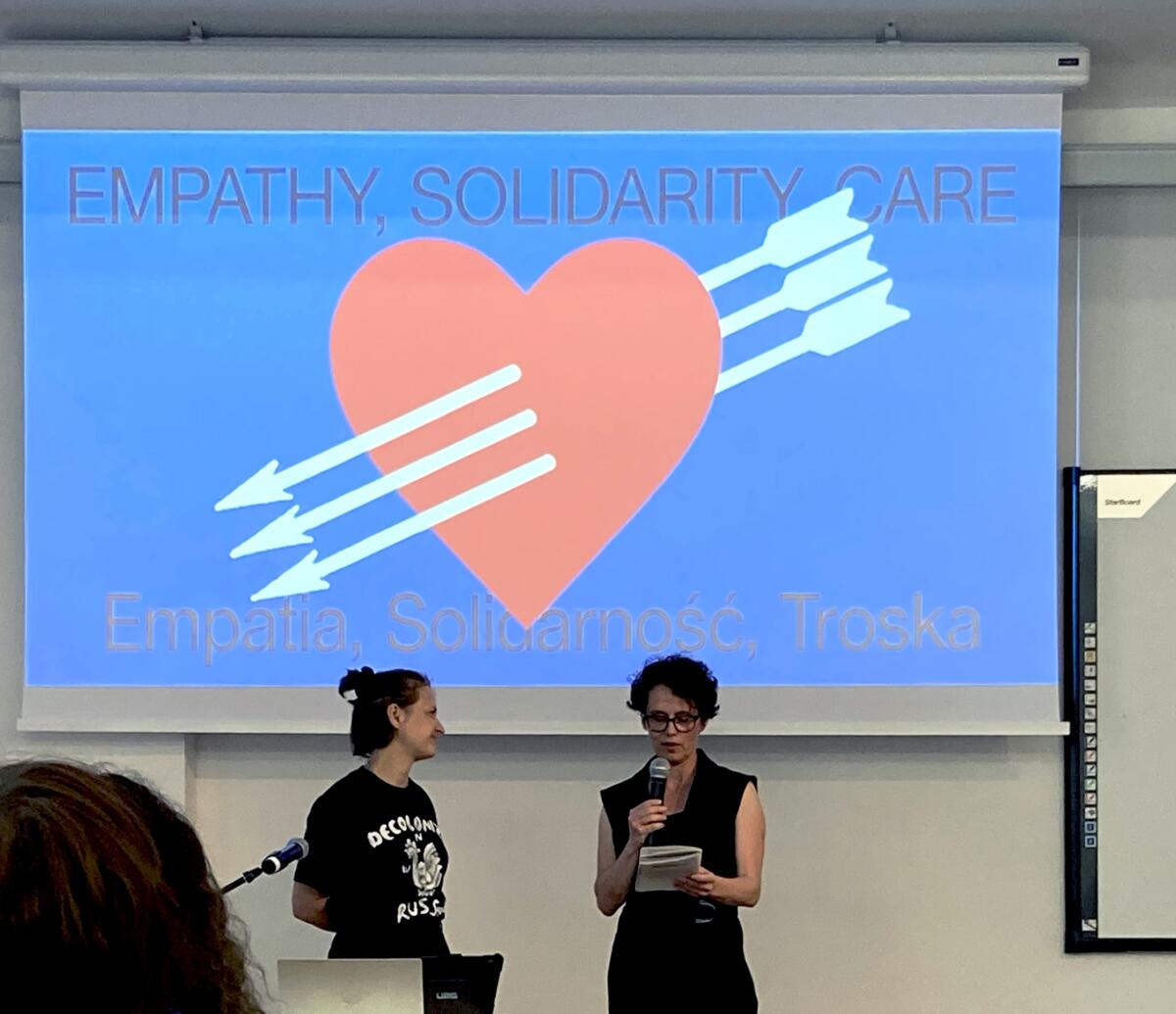

This is how moderator Manca G. Renko opened our roundtable Art Magazines for the 21st Century: Amid Challenge and Perspective, which was hosted by Cukrarna Gallery during the opening evening of Ljubljana Art Weekend. Now you’re sitting here reading this text, expecting something of value. And perhaps unexpectedly, value, the production of an art magazine, and the state of contemporary art is the exact thing I’m going to hover over here, despite the more seductive options for what could have been written about Ljubljana Art Weekend. Not to mention that this is also coming quite long after the fact (Ljubljana Art Weekend was held from May 25-28, 2023), the reasons of which will become more clear a little further on… because the way that we (small publishers with no funding, or reliable funding) function is problematic, and this problem is a symptom of a much larger dysfunction, which is a default in the world of contemporary culture / cultural production, and in the practice of creative labor in general. This text is not a battle cry, but rather an attempt to shed some light on the blurriness of cultural work and cultural production, to talk a bit more openly about the things that we all talk about mostly privately: the (what some would name) privilege (and I believe there is a measure of truth to this but it does not in any way describe the full spectrum of context) and burdens and the imbalances and Sisyphean tasks that befall the typically underpaid, or more frequently not paid at all, that are the foundations of this sector and that which keeps it afloat.

Those of us sat up on stage, the us being both editors of Kajet – Petrică Mogoș and Laura Naum (RO), Hana Čeferin of ETC. (SI), Tjaša Pogačar of Šum (SI), me from BLOK (PL), and Kate Sutton of Artforum (international), were asked a lot about the structure of our magazines, where we also ended up revealing some of our most ethically challenging practices. The question was asked “What is your position on workers rights? Doesn’t it devalue the work if someone says they will work for free, do you struggle with this idea, or are there ways to work for other things than money?” There are certain circumstances where working for free is not considered suspect (such as in emergency situations or for relief organizations, or if you’re an intern). An art magazine is not one of them. Someone mentioned that these platforms “open doors” (aka provide social capital), and that this is a big part of not only what we do, but a lot of how things are done in the art world. But, and this probably won’t come as a shock if you’re also currently working in culture, this doesn’t only relate to the magazine world, but essentially all aspects of the worlds of contemporary art and culture. It is not an aberration to be underpaid or to not be paid at all, it is rather the norm and it is (embarrassingly) expected in some cases – and has been for centuries. And yet somehow in contemporary art, we’ve also now entered an era of “rejecting” capitalism and the imperial systems that buttress just about everything, and forming alternate systems of community and valuation and care, and still a stigma remains around working for “free”. Value and art is an incredibly long-debated subject that has no clear answer and of course relates deeply to how we use art and how it is perceived against fields like technology or finance, and also how we continue to view the role of the artist maybe because we are still holding onto this idea that The True Artist Helps the World by Revealing Mystic Truths (Bruce Nauman, 1967). And of course despite all this, we also can’t overlook a critical element to all of this, in that we (at least those of us who were on stage) do this because it’s what we’re passionate about. We believe in the work we do, its impact and import; we enjoy it and are grateful to have created platforms that are meaningful. But despite how good our hearts feel and how much better we might be able to sleep at night considering how soul-fulfilled we are, there’s still the matter of the material world and needing money to survive. The palace at 4 am is an anxiety-filled place.

There is very little desire (at least personally) to encourage the mythology of the “starving artist” (sub: cultural worker) but instead to question and start to really deeply examine this deeply held (and also warped) relation to performing cultural work because it must be done, which is entrenched with this notion of passion that of course makes it so easy to discount or to find excuses for not being able to properly quantify. And I would be remiss to not confront the fact of privilege, which was a sentiment stated clearly during our round table. Not everyone has the privilege of “working for free”, and by qualifying this with quotes, I am attempting to also point out the fact that no labor is in fact, free, even if it is unpaid. As writers, editors, and publishers, we are constantly confronted with ethical decisions but more and more we are forced to confront the ethics of our own working practices, which for some, there is no clear answer. Many of us are self taught, and have come into writing and publishing from different realms – as makers, curators, and otherwise consumers or producers of contemporary art. How do we continue to produce and disseminate critical work in a deeply dysfunctional, unstable, unfair and often toxic environment of the contemporary art world? Can we confront the relation of privilege, and visibility, even in these cases alone, of who can earn enough in other jobs to “work for free” in culture? Or who has the support to do this without worrying about when the fee will actually appear in the account? The art world has largely been bankrolled and paved by the elite, but that doesn’t mean those are the only ones who have a seat at the table.

More often than not, funding dictates content, which is also a big part of how things are shaped or viewed or made viewable to a broader audience. During our talk, Hana of ETC. referenced EastArt Mags, a (no longer functioning) consortium created through the Visegrad fund which excluded Slovenia simply because it was not a part of the Visegrad group, despite being so culturally enmeshed. These kinds of relations and networks have a direct effect on visibility and viability. Not to mention who is able to pay for ads or who has time to visit what exhibition and who knows which writer or gallerist or collector, etc. I thought about this and actually talked with and listened to others share a lot about it in my few days in Ljubljana. Reviewing the program I noted a strong emphasis on direct confrontation with the state of both production and viewing of contemporary art: what is working and what is not. The discussion before ours invited representatives from the city and the program manager of the European Capital of Culture 2025 to sit alongside artists to discuss Space for Work: The (In)accessibility of Studios. And, on the first afternoon of the art weekend there was a walk curated by Tjaša (of Šum) through alternative/independent and otherwise precarious working spaces of artists and cultural workers in the city. The strong presence of this sector, along with the blatant acknowledgement for how much does not in fact work, or contribute to the health and wellbeing of these workers, was to say the least, refreshing. Too often the independent sector is abused in its role as a springboard for more formal and private institutions.

The morning after our talk, a colloquium called Museums for the Future was held at the Museum of Contemporary Art Metelkova (MSUM), where we heard from individuals working in major regional institutions who shared first-hand experiences of both the “zombification” of museums and its effect on contemporary cultural production as well as the heroic efforts being made to rescue and resuscitate these institutions who have been used as pawns in a range of political situations. Many of these people are working with their hands tied; facing continued slashing of funding, the cancelation of programs without notice, often after deep time and monetary investment, or having to fight for the museum to simply remain and not have it bulldozed into a literal parking lot. And what happens when a generation who has learned that it cannot rely on institutions comes of age? When we’re no longer accustomed to having access to researched, nuanced, and high-quality exhibitions that in some cases, have been years in the making, bringing together voices and perspectives that are not readily accessible in the everyday? In every sector there is a break that needs to be mended.

Going back to the roundtable: in what felt like some kind of accidental confessional moment, one of us admitted that we’re really bad at responding to emails. Almost without hesitation the rest of us sheepishly echoed this “bad” practice, as if it made us appear less professional or serious about our work (I write this after discovering a few days ago that my email for the magazine stopped receiving new mail almost two months ago). But really what it revealed is that we’re all doing this primarily as a labor of love and because of a want to see this kind of work in the world. And of course I would be lying if I didn’t admit that it also comes with a certain amount of soft power. Do not misread this as a ploy for a pat on the back but rather as (at least personally) a desire to not be a part of what is contributing to global – and very, very local – fascism, to be a part of the resistance, which includes opportunities for criticism, for dialogue, for dissemination of information and for championing the people and work that is being done to challenge this slow and violent chokehold.

The closing question from the moderator was “If we could have all the money in the world, what would we do? …if we can work beyond money, can we think beyond money?” Almost without thinking, each of us kind of casually muttered something about getting paid, which somehow was interpreted as a lack of ability to even dream: we didn’t have some grand design for what we would do with unlimited funds. We would simply pay ourselves and all those that work with us a living wage. But this is in fact the dream. The dream (which also is a twisted net of both privilege and resistance) is to keep doing this work but with stability. With stability and the ability to employ better practices, to be more feminist, more anti-colonial, less ableist and more accessible.

So maybe next time we can challenge chatGPT to tell us instead of how to start an art magazine, how to actually get paid for running an existing one. How to make cultural work more equitable, and how, in fact, to value culture to begin with. Until then, I’ll keep dreaming.

Imprint

| Place / venue | Ljubljana Art Weekend |

| Dates | May 25-28, 2023 |

| Index | Artforum BLOK chatGPT Cukrarna Gallery EastArt Mags ETC. Hanna Serefin Kajet Kate Sutton Katie Zazenski Laura Naum Ljubljana Art Weekend Manca G. Renko Museum of Contemporary Art Metelkova (MSUM) Petre Mogoș Šum Tjaša Pogačar |