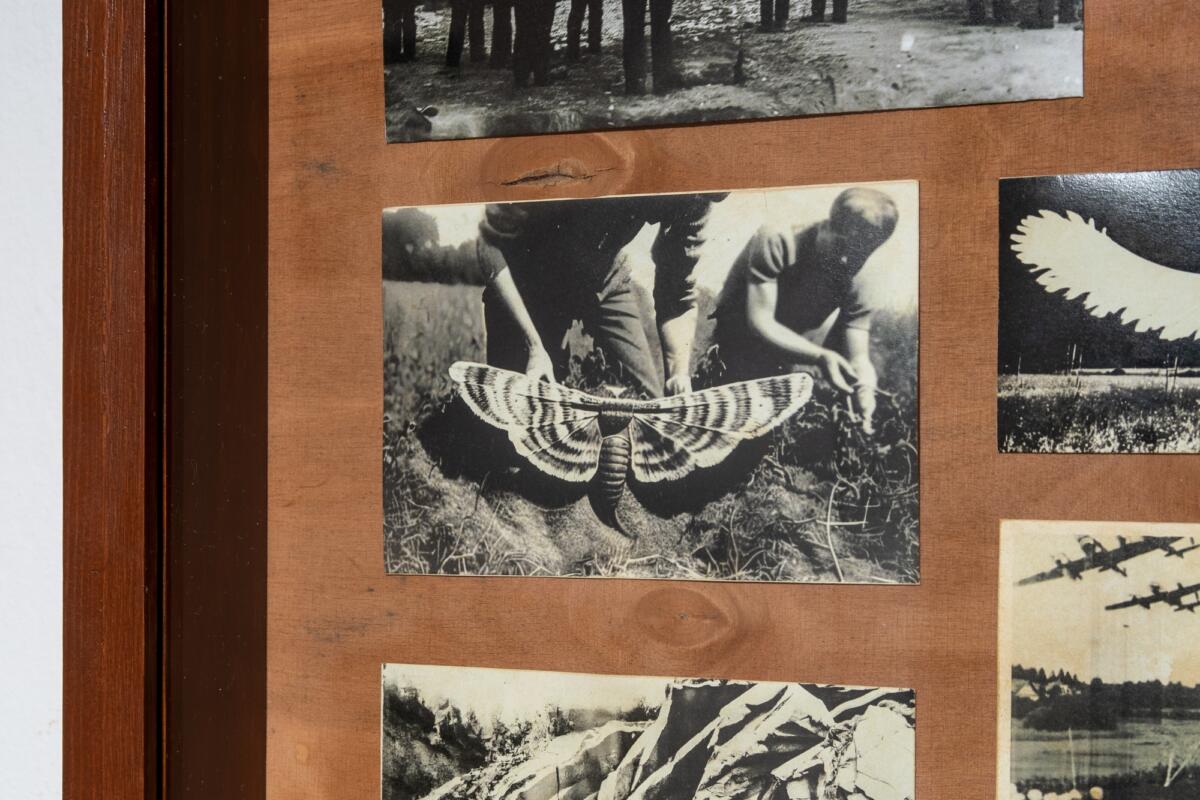

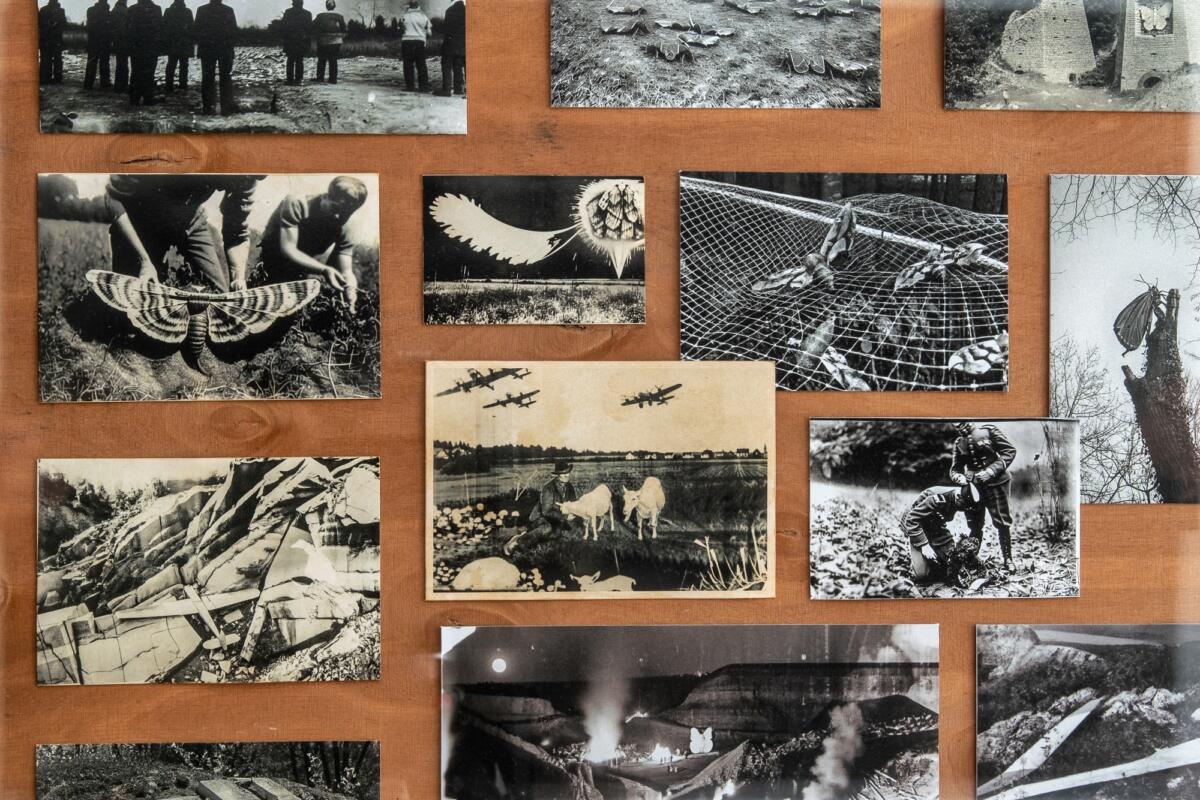

In a Warsaw neighborhood, behind some military barracks and the Geological Museum – two landmarks that turned out to be quite fitting for our subject – we walked past a man carrying a carton of milk up the stairs of a late socialist realist residential block, to the apartment-based gallery called Barbara Baryzewska, curated by Andrii Dostliev. The word “gallery” was scrawled subversively in marker on a piece of masking tape underneath Barbara’s name plate. We had no idea what was in store behind that door at Mateusz Piestrak’s exhibition Nieder Ellguth: The Flying Archive. We entered, or rather jumped, through time, space, and reality itself. The exhibition was presented in the former living room and at first sight, it was an archive alright, but quite an unusual one: it combined the pre- and post-war aeronautical history of the Silesian village, Nieder Ellguth, today called Ligota Dolna (or Lower Liberty – if we were to risk a tentative English translation), as well as the first ever homage to the marginalized history of the butterflies that once inhabited the region. A series of black-and-white archival images filled the room, but something was discomforting in this documentation: there was a certain disproportion in the images. Slowly, a fantastical element descended. Did I really just see a giant moth the size of a rabbit?

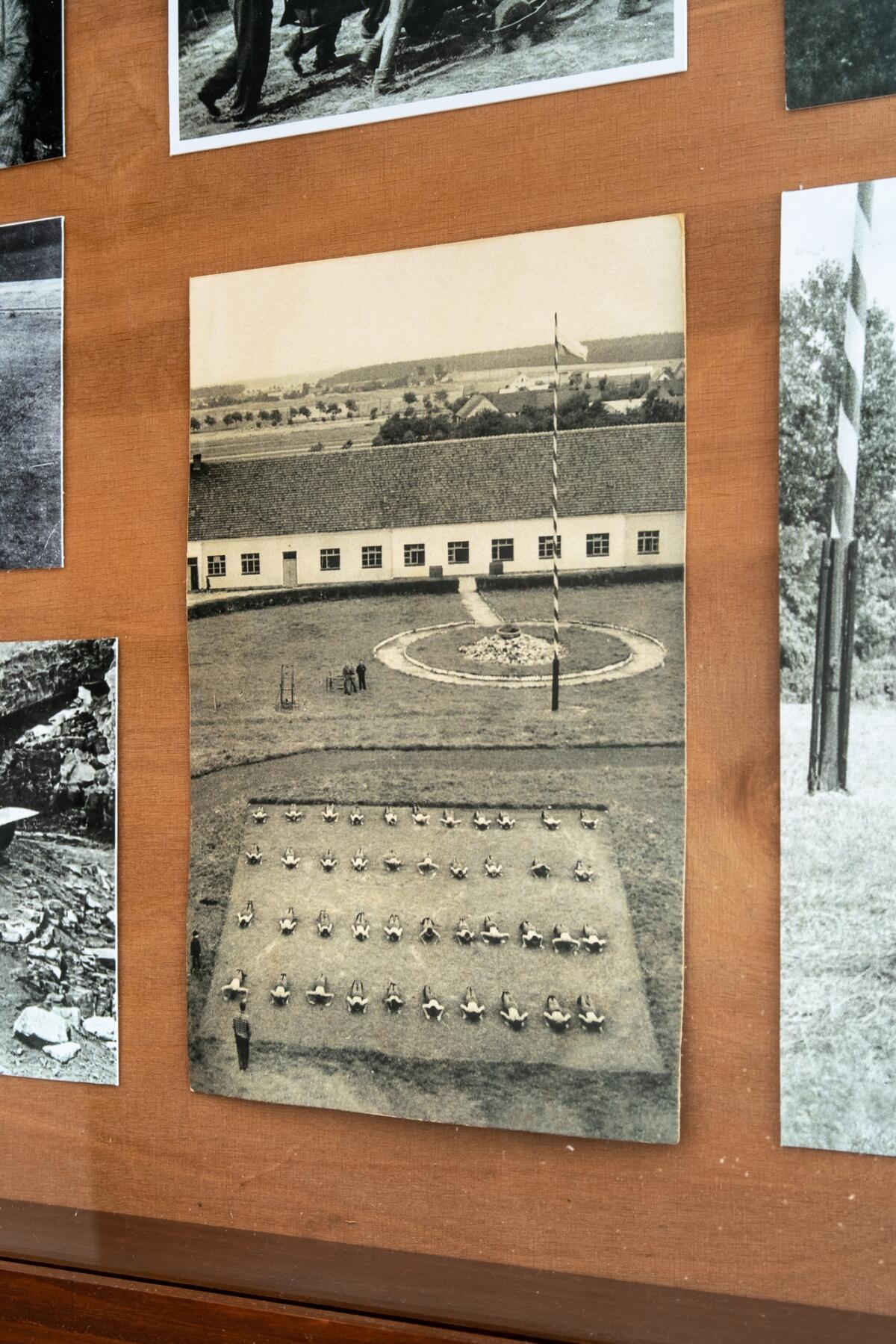

On the left wall were four shadow boxes composed mostly of neatly-arranged small photographs, and in the center of the room was a slideshow of some of the same images, enlarged and projected onto a screen by a carousel slide projector. On the opposite wall from the boxes were two images, one seemingly acrylic on canvas and the other a large format enigmatic map. Three of the four boxes displayed photographs, mostly brownish, seemingly old, black-and-whites, archiving the village’s past. The fourth box held 15 biological specimens of butterflies. The nature preserve of Ligota Dolna, we learned later, was home to 599 different species of moths and butterflies. A Polish-language paperback publication about butterflies of the area was haphazardly lying on a sofa nearby and supposedly served as proof of this. Although the placement of the book invited patrons to pick it up and engage with it, it was at risk of going unnoticed. The soundtrack that evening was the cyclical clicking and exchanging of slides as they fell into place, as well as the artist himself elaborating on his work in a constant loop of anecdotes that kept changing, just as the slides and the history, or reality, of the village itself. All of this seemed to be part of the installation and may have been, like the rest of the exhibit, part archive, and as it turned out, part fabrication.

The images within the shadow boxes showcased a rich and fanciful history. We saw pilots preparing for and dealing with the wreckage of war, homely women contributing to their households in domestic and social ways by gathering or decorating with butterflies, and nature full of moths and butterflies of unprecedented size. Although the rabbit-sized moths were still acceptable to a certain degree, the plane-sized UFOs were definitely calling into question the nature of truth in this particular archive, or potentially all archives. It was perhaps a reminder of the belief that photography as a medium for truth is questionable, a reference to Martha Rosler’s Decoys and Disruptions. There was also a still-standing stone monument with references to Icarus, once a lime kiln which later became a monument to the nazi pilots. The photographs also included images of village infrastructure that incorporated giant sculptures of moths and butterflies into their designs. The aeronautical images reflected in the daily life and architecture of the village nicely illustrated humanity’s desire to replicate or perhaps honor nature in flight.

Some images in the exhibition came from the archives directly, some began in the archives but were altered seamlessly by the artist, some come entirely from modern life, and others yet were generated using various AI tools. Because of the black and white photography we lost our ability to date the images and so too, lost track of time and even reality. The artist’s use of a slide projector rather than a digital projector casting images from a laptop, only added to the archive or museum-like feel of the place. The artist elaborated in great detail on his fabrication process, outlining which images were “real” and which ones were “transformed”, but without this narration, each of the images were presented as completely valid works of history. The installation gives the viewer a sense of anthropological exposure, highlighting a place, people, and culture that was previously at risk of being lost or forgotten. A type of misplaced nostalgia even emerges for how the world has changed since then, yet it never – as far as we know – existed, at least not in the form presented. It is a mélange of fact, fabrication and fantasy, but to quote the artist, “the history of this village is even stranger than what I was able to create.”

We found ourselves in a freefall of time and space. What was presented as true – quite literally in black and white – was called into question before our eyes. This playful blurring or suspension of reality is reminiscent of fairy tales where individual characters, like these butterflies, are larger than life. The images of pre-war pilots and airplane hangars hearken back to young boys playing with their toy planes, or running down hills with their arms stretched out like wings. This boyhood element was further amplified when we learned that the artist himself lived in this village as a kid. The archive thus became not just a history of the village but a chronicle of childhood, how a boy might view the community where he just moved, with all its mysteries and glories. The atmosphere of the exhibition, its playfulness, its transformative character and abundant imagination, also hints at a return to the obsessions of childhood or rites of passage. The making of the exhibition itself resembled a child-like sense of play, “generating the images with AI software was like a computer game,” as Piestrak commented.

To make this fabricated archive believable, the artist deployed an impressive amount of technology and research. Had his manipulations been made in a more rudimentary way, the believability of this fabrication would have been undermined. Instead, his careful and adept use of digital photography techniques and his astute eye for where adjustments would be both plausible and provocative created a true alternative world (but to what extent alternative?). The artist claimed he used AI to generate images mostly of settings for which there was no archival evidence, but which “likely took place,” he said. The irony of using computer-generated algorithms to depict common life seemed intriguing. AI was not used to make history more grandiose – generating images of Picasso or Hitler, for example, holding butterflies in the villagen (both of whom apparently visited). He used AI to generate a plausible, common-place reality, or to correct it. Without widespread use of cameras at that time or living residents remaining, there is almost no way to refute any edits made to this past.

The slide show was another impressive display of technical skill. In order to create the slides used in the exhibition, the artist first prepared digital images, printed them, took film-based photos, developed the negatives and used them to create individual slides. The precision of today’s technology had to be adjusted. The digital photographs he prepared and the clarity of the negatives he produced had to be blurred in order to seem old enough and thus increase the believability of the archive.

The projector really set the scene for an almost academic presentation and created the pretense by which the viewer was encouraged to surrender to the images. The set-up of the projector also rendered it more as a sculpture or installation, not just a means to an end. The stool for the projector was constructed specifically for the exhibit, the shape of which resembled the images of Icarus’s tower from Ligota Dolna, which the artist took the same liberty by visually demolishing it through a series of paintings a few years ago. On the one wing there is artistry and rehabilitation, but on the other, there is intervention and erasure. A sheet stretched over a string served as the projector screen but it also echoed an image of villagers using a sheet in the meadow to attract and catch moths. The cycle of images that went by drew us in. Each image stayed only for 10 seconds before disappearing again. This duration enabled us to look deeply into the world depicted and to piece together a narrative of this unusual village. It also allowed us enough time to inspect the image, looking for deficiencies of some kind that would confirm whether or not the image was real. But, as soon as we looked closely, the image was replaced by the next, never really allowing the viewer to confirm or deny the mystery that was unfolding. The projector also served as an interactive hook for participants as it stimulated comments from the artist and impromptu Q&A.

The curation was excellent, and not just related to what was on display in this apartment-gallery. Across town, the curator, Andrii Dostliev, – has an exhibition of his own work, Blood and Flowers at Biuro Wystaw. Dostilev tackles there the issue of photographic archives from a similar war-time period, but from a different perspective: looking at their commercialization and the use of watermarks and other visually-added interferences. The wartime imagery is reminiscent of our current environment. In the near future we will be dealing with the ramifications of today’s war and we might find know-how in processing those memories in exhibitions like this.

The thoroughness of displayed objects in The Flying Archive was extraordinary. Echoes of the exhibited works were everywhere: the small photographs in the shadow boxes were displayed in large format on a sheet screen. The digital print of a fantastic aerial landscape view of the village, altered to incorporate butterfly-shaped buildings, farmland, and surrounding streets, was mirrored in miniature on the pattern found on the wings of the Araschnia Levana ( Map Butterfly) on display. The Rorschach-esque painting done in black and white, of a Janus-faced Nazi officer-turned-moth, mirrored another encased specimen, the Papilio demodocus (Citrus Swallowtail). The color and beauty of the 15 butterfly specimens were so astounding that we started to doubt the legitimacy of these creatures as well. Were they fabricated? Maybe also the research publication on the sofa corroborating their existence was an artfully made counterfeit? We had lost all frames of reference for reality.

Despite the efforts to generate an archival feel with black and white images and the slide projector, a few photographs, including one from the artist’s own childhood, were displayed in color. Perhaps these images were an intentional spectrum-like transition to the rainbow of colors that followed in the case with the 15 butterflies, but they did seem slightly out-of-place. So too were the steel pins that were used to mount the butterflies in their case. Their colored, pearly tops distracting from the already-brilliant wings they pinned into place. But it was also proof that the work was assembled by a human.

The amount of time and energy that went into finding, accessing, reviewing, and restoring these archival images, and then their meticulous manipulation, is mind blowing. Seemingly believable yet somehow also incredible. There was also the effort of tracking down a working slide projector and to create modern day slides along with the research that went into understanding and then ordering 15 stunning butterflies and mating them for display. We even learned that the artist himself built the wooden frames of the shadow boxes, no surprise that it matched the perfectly-proportioned stand for the slide projector. Indeed, Piestrak’s own statement introducing the archive noted, “After years of work, I am happy to present my findings for the first time.” We attempted to congratulate this multi-dexterous artist-anthropologist on his labor-of-love that had clearly consumed his life for years like many peoples’ doctoral thesis, but he smirked and said it had been just a few months. In that moment we knew: we were flying through different realities.

Edited by Katie Zazenski

Imprint

| Artist | Mateusz Piestrak |

| Exhibition | Nieder Ellguth: The Flying Archive |

| Place / venue | Barbara Baryzewska gallery |

| Dates | 9-16.06.2023 |

| Curated by | Andrii Dostliev |

| Index | Andrii Dostliev Barbara Baryzewska gallery Basma Bamia Mateusz Piestrak Oett Redja |