Entry to Galerie Rudolfinum by a side door and service elevator misses the impact of its grand staircase, which usually has the effect of making me feel underdressed. It also disrupts the usual insistence that exhibitions here must be seen from beginning to end in an anticlockwise direction. I miss the beginning—Anetta Mona Chisa and Aleksandra Vajd’s curtains, which cover completely the first floor colonnade—and only get to see them from behind, emphasising that this exhibition is closed and I am here alone.

This seems perhaps how Compassion Fatigue is Over was intended to be seen, not as a blockbuster tourist conveyor belt that might have been here in past summers but a solitary experience to get you through the end of winter. Compassion fatigue is a psychological response to the exhaustion of caring for others, either because it’s our job or a role society demands of us. To protect ourselves we stop being able to care about anything. The exhibition sets itself up as therapeutic—or at least what the curator calls a “temporary solution”—with the hope that we might “function better” after we leave. The long-form films and videos tell stories we’re asked to connect with emotionally. It also wants to be a therapy for a more general attention fatigue. It’s prescription is to silence our phones—“temporarily mute the flow of notifications”—and relax into a different mode and speed of looking.

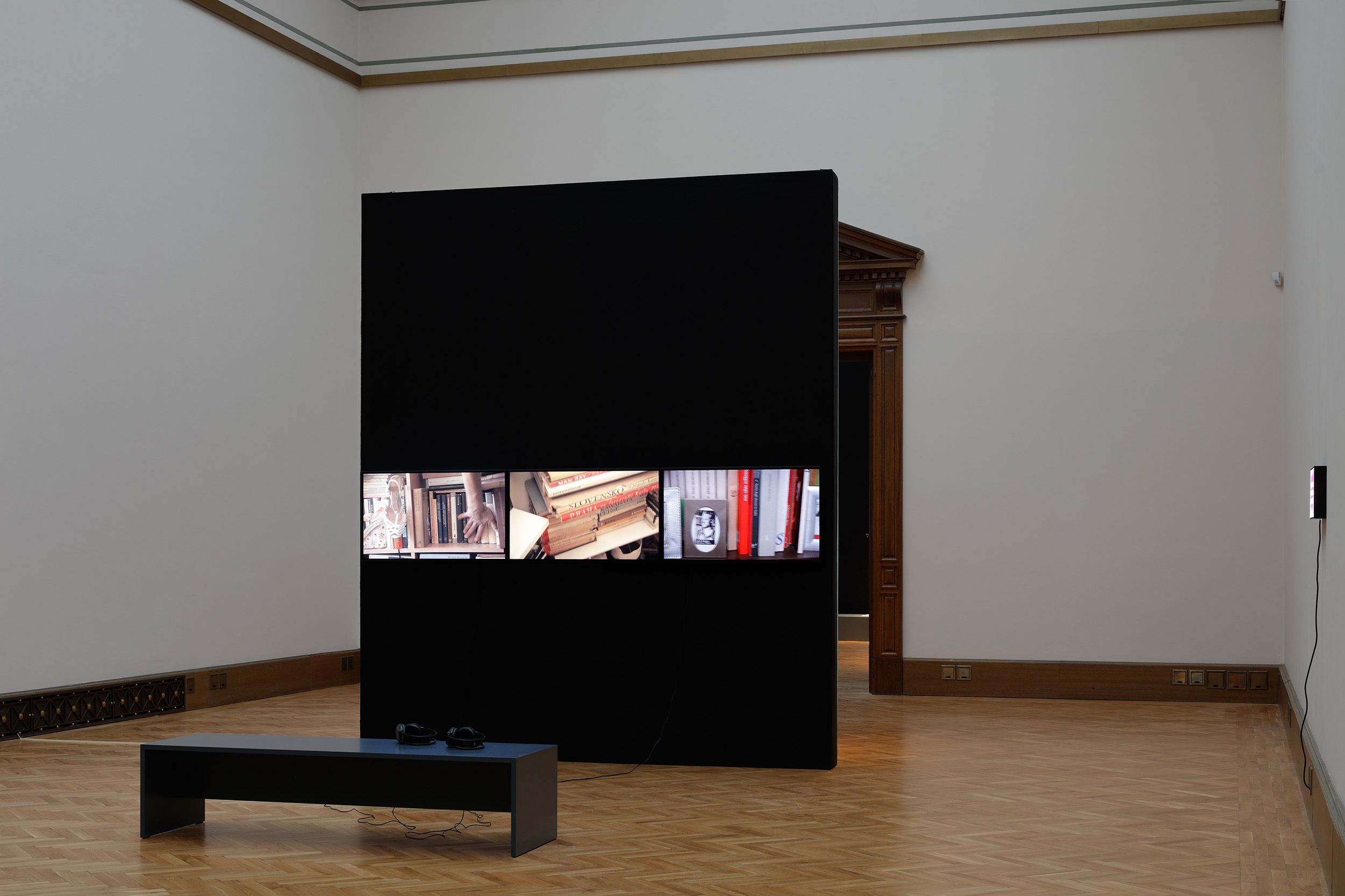

Anna Daučíková, ‘On Allomorphing’ (2017), installation view of ‘Compassion Fatigue Is Over’ © Galerie Rudolfinum, Photo Martin Polák

Individually, each of the works is well chosen to do this. As well as centring characters—some real, some not—who’s own capacities for care and empathy are stretched and sometimes broken, each artist uses the specificities of moving image to think about how the act of storytelling changes the way we process emotions and relations. In Candice Breitz’s Sweat (2018), members of the Sex Workers Education and Advocacy Taskforce tell their stories and advocating their politics with verbal precision and high definition, reading their own words with the camera locked tightly on their moving lips. Anna Daučíková’s biographies and autobiographies are told from behind the camera. In Thirty-three Situations (2015), scenes and dialogues from 1980s Moscow are typed and inserted into shots of contemporary Prague, memories of banal and petty brutalities and indignities intrude into, but do not interrupt, the present. For the three-channel On Allomorphing (2017), Daučíková narrates overlapping histories through collections of books, shoes and photographs.

Hito Steyerl’s two best-know works (November, 2004; Lovely Andrea, 2007) are the stories of images—pornography, propaganda, protest placards—that describe her relationship with her childhood friend Andrea Wolf—murdered and martyred by the Turkish army—and with her own younger self who posed under Wolf’s name. Trying to pin down the truth behind fictions is shown as an uncomfortable, and in the end futile, act. The vastness of Naeem Mohaiemen’s widescreens and the emptiness of the rooms they’re shown in reflect his films’ locations: an abandoned Athens airport of the fiction film Tripoli Cancelled (2017) and an empty UN assembly chamber for the documentary Two Meetings and a Funeral (2017). These are backdrops for characters and their stories of 20th century disappointment, both personal in a story loosely based on his father and geo-political in the account of failure of the Non-Aligned Movement. Jeremy Shaw’s I Can See Forever (2018) is most explicit in its play with formats. The third part of his Quantification Trilogy, this para-science-fiction starts within the conventions of television documentary, telling a historically unplaceable tale of human enhancement before the analogue video glitches into expressionist digital images and computer graphics as it loops around to its beginning.

Hito Steyerl, Lovely Andrea, 2007, single channel video; sound in English, Japanese and German with English subtitles; color. Duration 30 minutes. Courtesy the artist, Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York and Esther Schipper, Berlin. © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2020. Film still © Hito Steyerl

There are connections between each of these works. They’re all very good—international standard—exhibited in biennales and museums across the world. They all have something to say about both their subjects and their medium, with the fictionalising effect of moving image often centred. The exhibition guide gives Haris Epaminonda’s Chimera (2019) the task of cohering the other works, suggesting it as a key to how we might make connections between them. Her super-8 camera captures shopping channels, tigers, solar power plants and Konstantin Tsiolkovsky’s cosmist drawings. The grain of the film blends the subject matter while the camerawork makes each thing visually interesting, but the specificities of what we’re being shown are less important than the overall effect.

In a similar way, the exhibition invites you to drift through rooms, making your own connections between each work. The electronic signage on the walls encourages you to take breaks, come back later, view works in any order. The galleries are described as projection rooms or cinemas, but this is not quite the case. Even at its most art house, cinema is a collective, if anonymous, experience. Here you drop in and out of films in the middle, there are 30 minute works where you’re not even given a place to sit. As a result, there’s no chance of seeing the same thing as someone else. Each experience is individual. Only Vajd’s photograms—abstract geometric arrangements of photographic paper in flat tones and hues—will be seen by everyone. But, like her architectural collaborations in fabric with Mona Chisa, they are used as breathing space “for the projection of our own readings” rather than a chance to solidify any of the possible connections between works.

Aleksandra Vajd, ‘The Thirty-Six Dramatic Situations’ (2019), installation view of ‘Compassion Fatigue Is Over’ © Galerie Rudolfinum, Photo Martin Polák

The effect of this is deeply unsatisfying. My desire for the last year to visit a gallery was not, it turns out, caused by missing artworks themselves. The works by Breitz and Steyerl are freely available online, Epaminonda and Mohaiemen’s are too if you know where to look (I download Chimera, watching it while I write this and, unlike in the exhibition, see it from beginning to end). Instead, what I have missed is being in public, having the kind of shared experience that the gallery or cinema allows for. Without other people there, drifting through the gallery starts to feel the same as browsing a YouTube playlist, stopping for a while on something interesting, skipping forward to the next thing, knowing you can come back later. Though you can see exactly how many other people have viewed a video, only you will see it this way, a unique path through a shared cultural space. This feeling of isolation is heightened, of course, by the fact that almost no one will see this show, but in a different year, I wonder who would see it? How many people could take the eight hours—over one or many visits—necessary to watch everything from start to finish? The answer, I am sure, is none. Whether the gallery is open or closed, no one would ever or could ever see each of these works in their entirety. On our own we can have important emotional experiences with artwork, but they’ll be lonely ones. Galleries, like cinemas, are social spaces, though not in the sense that they’re a place we meet and talk. We don’t need to visit an exhibition together to share an experience of it, but we do need to see the same thing in order to develop a shared response, to see representations of ourselves and others and decide to accept or reject them. Public institutions socialise us; atomised experiences, online or off, make this impossible.

Naeem Mohaienem, ‘Tripoli Cancelled’, 2017, installation view of ‘Compassion Fatigue Is Over’ © Galerie Rudolfinum, photo: Martin Polák

After 12 months of isolation, we’re in desperate need of socialisation, of finding concrete spaces, objects and ideas we can share and respond to together. If so few people are going to see an exhibition, even in normal times, wouldn’t it make sense to think more clearly about who these people will actually be, what they might want and need, and what they might not find elsewhere? Galleries can do more than educate an undifferentiated public through examples of quality. If we know beforehand that it’s all ‘very good’, don’t we limit the range of responses, collective and individual, that are permissible? When galleries do reopen, drifting through them to make meanings that are unique to us will not be the therapy we need. Public institutions might have to care more about how we can share an experience of art, and demand a little more of us as viewers.

The text first appeared in Czech language as Únava z osamělosti není za námi in “Artalk.cz” magazine on 29.03.2021

Imprint

| Artist | Candice Breitz, Anna Daučíková, Haris Epaminonda, Naeem Mohaiemen, Jeremy Shaw, Hito Steyerl, Aleksandra Vajd & Anetta Mona Chisa |

| Exhibition | Compassion Fatigue Is Over |

| Place / venue | Galerie Rudolfinum, Prague, Czechia |

| Dates | 21 January – 18 April 2021 |

| Curated by | Jen Kratochvil, Petr Nedoma |

| Website | www.galerierudolfinum.cz |

| Index | Aleksandra Vajd Anetta Mona Chișa Anna Daučíková Artalk.cz Candice Breitz Galerie Rudolfinum Haris Epaminonda Hito Steyerl Jen Kratochvil Jeremy Shaw John Hill Naeem Mohaiemen Petr Nedoma |