A few weeks before the full-scale military invasion of the territory of Ukraine by the Russian army, my social media feed was full of sunrises, sunsets, and landscapes. On February 24, the beauty of the sunrise was stolen from us.

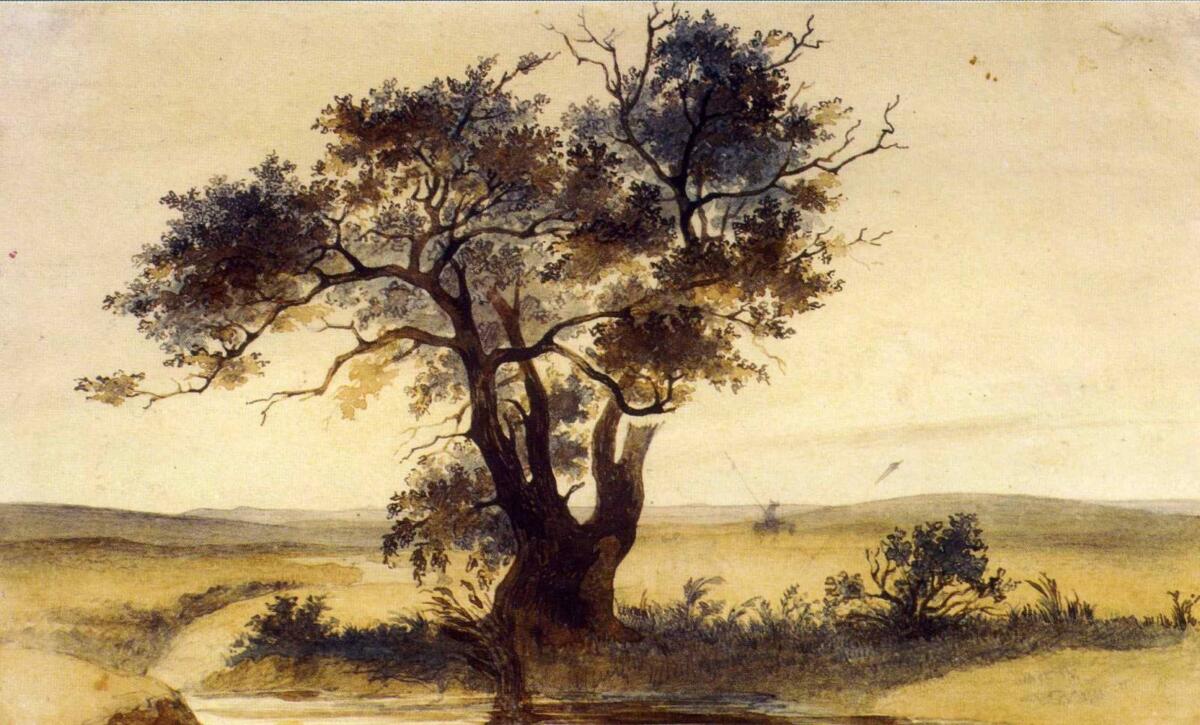

“Some drunken Cossack officer thought of cutting down and burning a tree for his own amusement. And this barbaric act went unpunished as if it were not a criminal or the most heinous crime,” said Alexei Maksheev, an officer in the General Staff of the Russian Empire. This episode took place during the Aral Sea Expedition (1848-1849), organized by the Ministry of War of the Russian Empire to “research the natural resources of the Aral Sea” in order to arrange future shipping routes and expand colonization by the Russian Empire. Taras Shevchenko, a Ukrainian artist and poet whose history symbolized the Ukrainian national revival and the struggle against enslavement, took part in that expedition. A serf by birth, he formed a canon in literature and art that remains intact. Like Maksheev, Shevchenko considered crimes against nature and environment identical to crimes against humanity. His numerous poems and drawings are evidenced, including his graphic notes made during the expedition. Shevchenko saw much in common in those landscapes with that which surrounded him as a child. And the horizon beyond which the sun fled reminded him of enslavement in his native land. His imagination and memories took the form of political imagination: Shevchenko dreamed that the day would come when his homeland would be free, and the landscape would no longer suffer from violence. As we do now.

Today, looking at the architecture of this war, ignited by the Russian Federation’s invasion of Ukraine, there is no doubt that these are the same Russian officers who commit acts of barbarism, destroying the environment and thus affecting the entire global ecosystem. To date, the most horrific and disturbing event of this nature was the capture of the Chernobyl nuclear power station by the Russian military, and the shelling of the Zaporizhzhya nuclear power station. Ukraine’s Energoatom (National Nuclear Energy Generating Company of Ukraine) warns that any intervention such as shelling and any other military action near the stations could lead to “violations of the nuclear and radiation safety of Europe’s largest nuclear facility, serious and tragic consequences for the world.” The Kyiv State Emergency Service has announced that explosions and shelling influence air quality conditions, increasing the level of pollution by 12 times.

Given the desire of contemporary Russia to build a strong connection with the history and ideology of the USSR, to conquer the land, not the people, is eloquent. For example, in the detailed history of Donbas, to which contemporary Russia so often refers, the landscape also occupies a special place. Thus, the Stalinist-era writer and poet Boris Gorbatov writes in his novel Donbas:

“Those blue mountains on the horizon were not created by God or geological upheaval. They were thrown out of the ground to the hill by a man and folded into pyramids, shovel after shovel. This glow over the steppe is not lightning, not the sun; this man fired a smelting from a blast furnace and swung imperiously at half the sky. […] The whole steppe lives and breathes human labor. It is all girdled with electric lights, the entire sky is in curly clouds of factory steam: and gentle and bluish smoke, agitated, rises from hundreds of pipes folded by human hands.”

This rhetoric of the landscape created by human hands erroneously leads to the wrong conclusion that these same hands have the right to change the environment. And we see how Russians try to show this in numerous Soviet movies about Donbas, as well as now with the military invasion of Ukraine.

However, the land, nature, and landscape are some of the most potent symbols that embody national pursuits, identity, and cultural issues for the Ukrainian tradition. And if for Gorbatov the land is first of all the subsoil or entrails, then in the Ukrainian cultural tradition, the land is first and foremost the foundation, that is, our roots. Hence, the close connection with the female image, which constantly experiences violence, especially as the “liberators” come to rape her. Symbolic in this context is a panel made in 1967 in Donetsk by two Ukrainian artists of the sixties, Ivan Lytovchenko and Volodymyr Priadka, entitled “The Land of Donetsk,” where the image of a woman is both an image of the land: she is depicted lying on her back. Thus her body shapes the landscape: her legs become hills, and her hair becomes wheat in the field. And today, looking through the tragic and horrifying photographs after the shelling of the maternity hospital in Mariupol, there is no doubt that this war has a female face, that war and violence are primarily aimed at destroying the female experience. Today, the Mariupol landscape is precisely these photographs of pregnant women under attack. Today, this exact picture represents the “land of Donetsk”.

As with art that reflects themes of occupation, migration, and war, the landscape always remembers the anxiety and devastation of people when they leave their homes. Thus, according to one of the first military photographers, Roger Fenton, who photographed the war in Crimea in March 1855, it is the devastated landscape that most endures the tragedy of the war. After all, the emptiness in the frame represents the emptiness that comes with war. It arises as a hole in peoples’ destinies.

For romantic Shevchenko, the natural environment always bears similarity to human beings through metaphors and descriptions. And any violence destroys subjectivity. In exile (1847-1850) for “writing poems in the Little Russian language” that “could be a possibility of Ukraine to exist as a separate state”, writing in his native language and even drawing, he especially understood the importance of resistance and struggle.

The history of the Donbas is also a history of constant resettlement; it is not only a narrative of the industry but also a narrative of survival, tragedy, and breakdown. For example, my fellow historian Kyrylo Tkachenko, who chose not to leave his native Kyiv, comprehends the experience of the life and resettlement of the Nogais[1], who lived in the territory of what is currently Donetsk and Luhansk from 1770-1860, thus destroying the myth of the existence of the Wild Field[2] and the historical monolith of Donbas. However, the story of the Nogais is only one episode of long regional history. Therefore, the phenomenon of the history of Donbas is ruined because the history of this region is much longer than just a period of industrialization.

Today’s Russian political imagination suggests seeing the Ukrainian landscape as desolate, paraphrasing Gorbatov, “it is all girdled with artillery lights.” However, the Ukrainian imagination is identical to Shevchenko’s romantic vision: it offers performative scenarios and scenarios for the emancipation of nature and the environment. He sees the landscape alive. As we are constantly seeing now.

Edited by Ewa Borysiewicz and Katie Zazenski

[1] The Nogais are a Turkic ethnic group who live in the North Caucasus region, as well as the territory of present-day Donetsk and Luhansk regions.

[2] The term the Wild Fields appeared in the 15th century and refers to the territory of present-day Eastern and Southern Ukraine and Western Russia, north of the Black Sea and Azov Sea.

Imprint

| Index | Kateryna Iakovlenko |