Ewa Borysiewicz: I’d like to start with the question about “Echoes of the Unseen”[1], your ongoing show at NOMUS in Gdańsk and your cooperation with the curator, Małgorzata Taraszkiewicz-Zwolicka. The exhibition includes a major survey of your projects to date, and I am curious about the selection process you opted for and whether you thought of this show as a kind of summary, a retrospective of sorts?

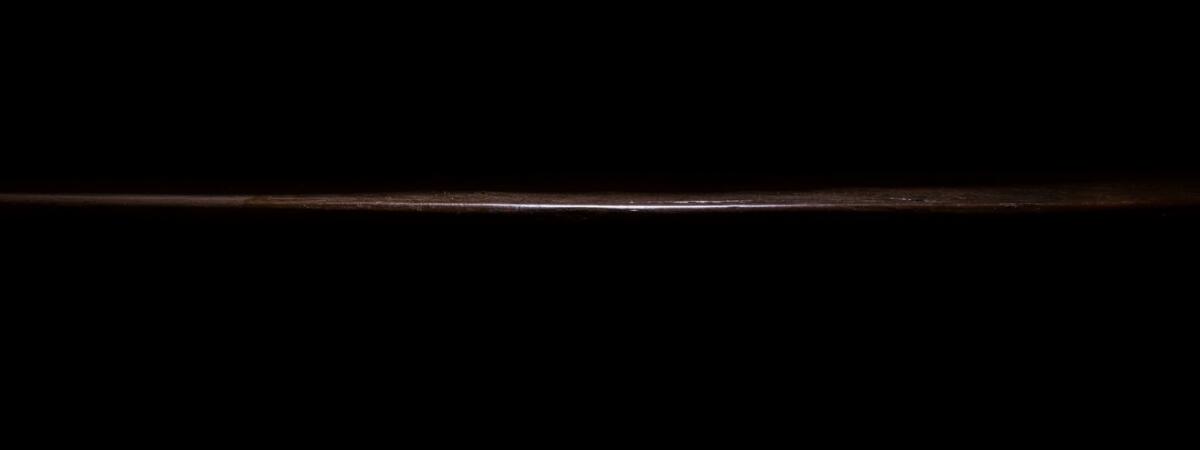

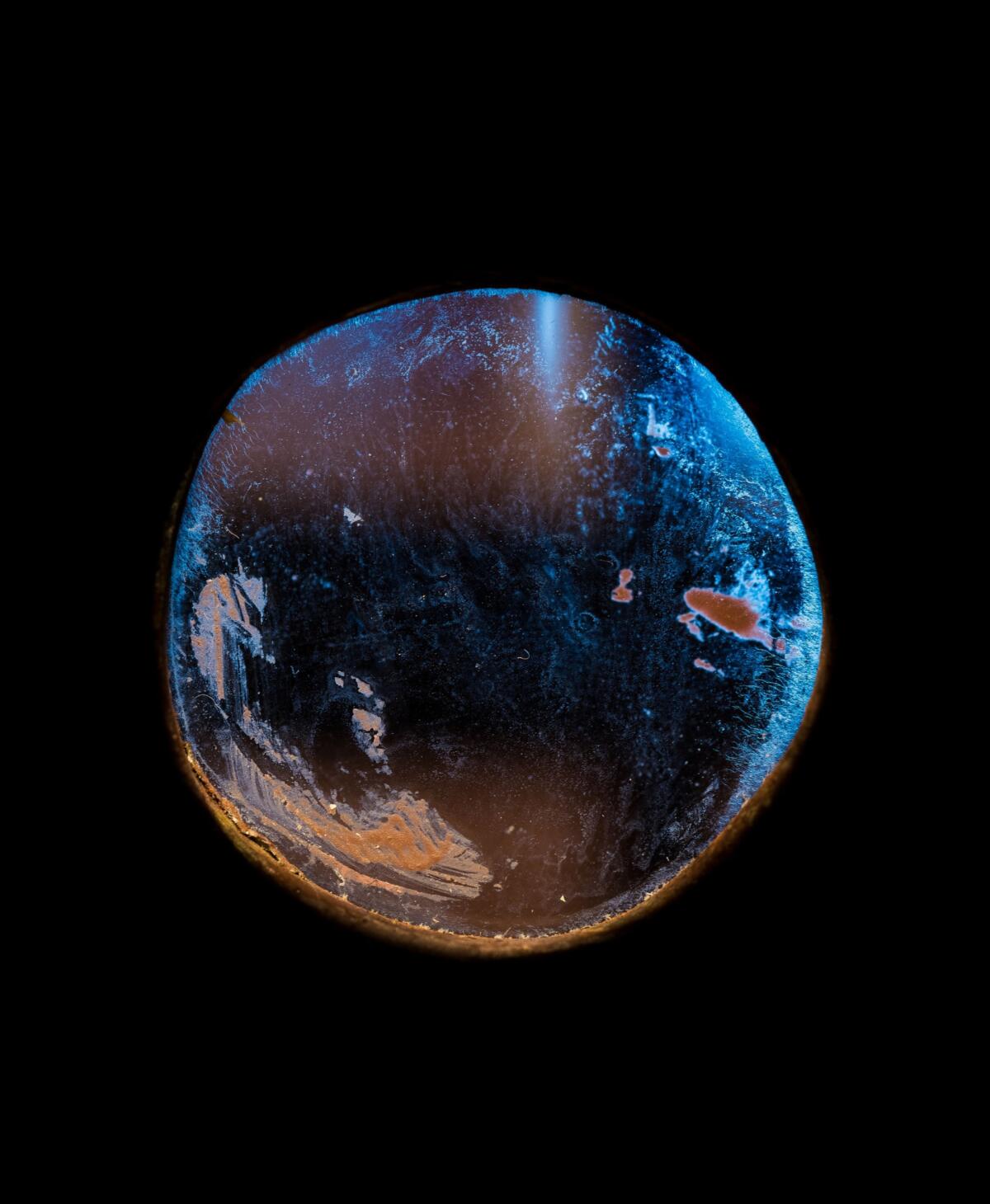

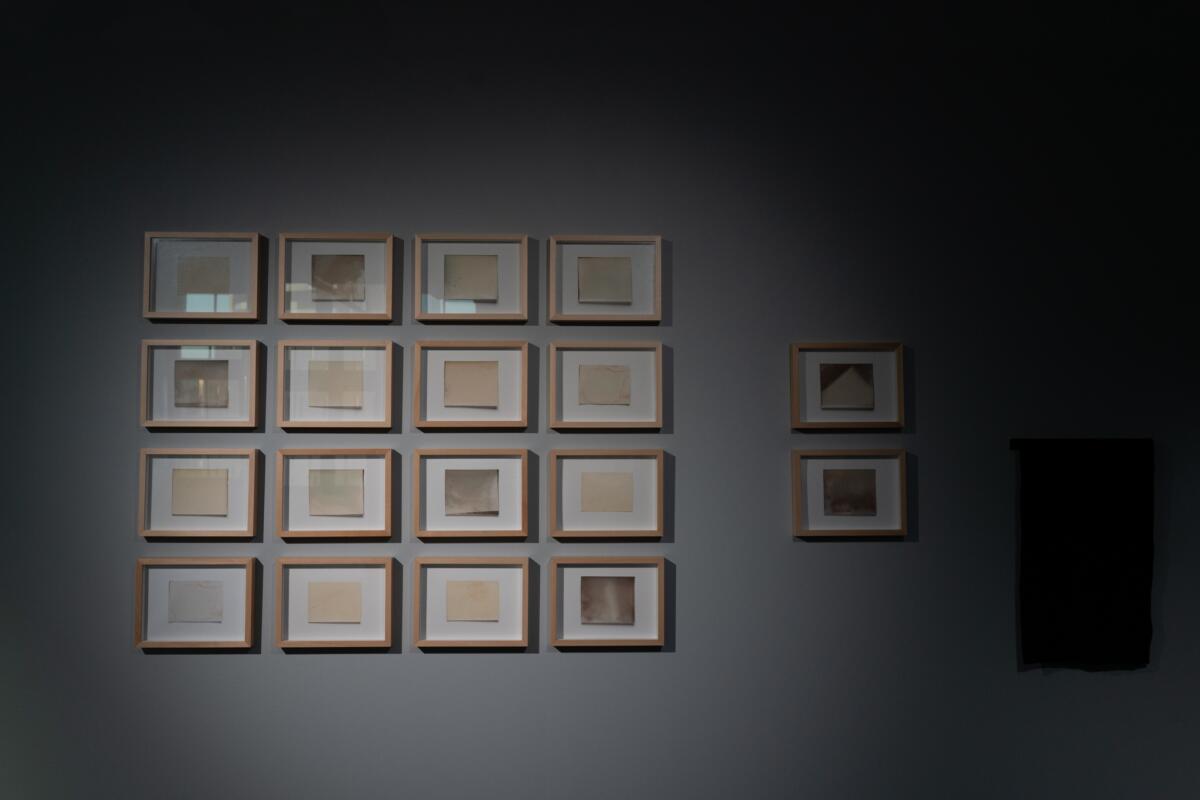

Valentyn Odnoviun: Yes, although I heard comments that it might be a bit too early for a retrospective… “Echoes of the Unseen ” contains almost all of my projects concerning oppressive regimes and socio-historical events in Eastern Europe and we decided on this subject at a very early stage of working on the curatorial concept for the exhibition. After that, together with Małgorzata, we made choices regarding the amount of work from each series we’re going to show. For example, the complete “Surveillance” (2016-2018) photography cycle depicting different prison cell door spyholes in former political prisons in the Baltic states, Ukraine, Poland, and Germany, consists of more than 60 images. For Gdańsk, we selected 15 works, as the most important aspect of this cycle is the concept itself, not the number of images. Some of the projects are presented in full, like “Horizons” (2018), where one can see grayish horizontal lines, set against an entirely black background, splitting the image in two. This series consists of only seven images, each depicting a stair-step leading to a basement used as a solitary cell in the former Gestapo, NKVD, and later communist secret police headquarters in different Polish cities. So the exhibition frames a large part of my work, but I am not sure what will come next, something entirely new or I’ll continue researching this subject further.

I wanted to ask you about your and Małgorzata’s method regarding the curatorial aspect of the show, since – in addition to working on artistic projects – you also have extensive experience in curating. You worked on the exhibition of Evgeniy Pavlov[2] and this year, you co-curated “Outsiders’ Look on Vilnius”[3]. I’m wondering how do you balance or manage that? Do you easily switch from one role – or field of competence – to another? Did you notice your curatorial expertise influencing your working relationship with Małgorzata?

I try to separate those fields of activity as clearly as possible and while I’m in one role, I try to suppress others for a period of time. I have a lot of respect for curators, designers, and architects approaching my work and it’s always interesting to see others interpret or think about how to present my work in a gallery context. Of course, I put some of my own thoughts into the whole process, but mainly I’m very open, so everybody can do their job.

Did Małgorzata propose an idea that revealed an aspect of your work you haven’t been conscious of?

We share a lot with Małgorzata and have a similar view on many things. We became friends pretty fast. So our work together was an efficient back and forth exchange. This does not mean it did not require significant effort from us both, but it was a very amiable and enjoyable journey together.

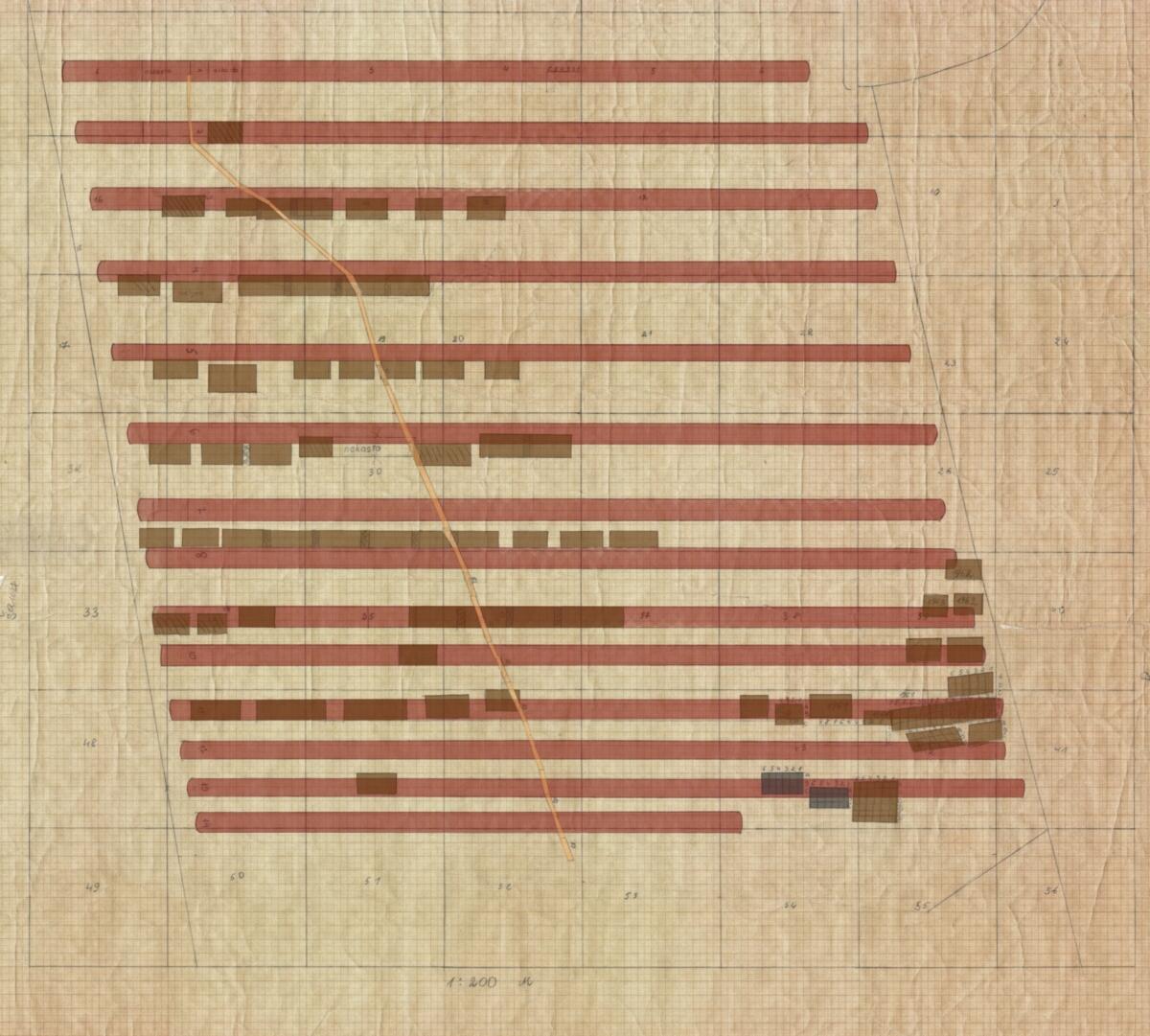

The preparations for the exhibition at NOMUS happened mainly online. Małgorzata shared some images of the space and a plan for the hang. Then I responded with my vision. And lastly, we figured out the final version in the gallery space. Our initial plan was realized in 80%, so you can say that the remaining 20% was a surprise for the both of us.

In addition to being an artist and curator, you work as an academic as well.

Right, this is another significant part of my working life. I’m writing my PhD on the topic of intersections and influences among Baltic and Ukrainian photographers and the creative impulses from Czechoslovakia and Poland between the 1960s and 1980s. And from time to time I’m curating exhibitions of some of the artists from this period, showcasing the photographers that were forgotten or are less recognized, like several Ukrainian photographers who moved to Lithuania whose works were previously not researched by Lithuanian art historians. I found out about their activity through conversations with Lithuanian photographers. In my work as an academic and curator – and this is also present in my work as an artist – I also use traces, scraps of information as a starting point and approach the subject in an investigative, evidence-based way. The most recent exhibition I worked on, the one at the National Art Gallery of Lithuania, featured two Ukrainian photographers, Jury Rupin from Kharkiv and Konstantin Kostiuk (Kostiukas) from the Volyn region. As I mentioned, very few art historians knew about them, but some artists and photographers did and they were my main source of information. So for “Outsiders’ Look on Vilnius”, I managed to locate Rupin’s and Kostiuk’s archives and selected a part of their oeuvre for the show.

Can you tell me what struck you in their work in particular?

I’d say that it’s a totally different kind of research if you compare it to my research as an artist. As an artist, I wouldn’t say that some of their ideas or aesthetics caught my attention. I used a contrasting, contextual approach, and focused on artistic exchange, cross-border cooperation and transnational influences. In my opinion, it’s very problematic that most countries research their heritage as isolated phenomena. In fact, there was a lot of collaboration, interactions, a flow of ideas that affected several republics or countries at once. Many photographers also had international contacts and an impact on one other, they were being featured in magazines distributed internationally. And my job is to try to reveal this network and to show a regional – rather than local – aspect of these processes. This moment in the history of photography is not that simple and you cannot solely reduce it to „national schools of photography”. Actually, it would be impossible to build them without an interaction with everything else that was happening around. So I’m not on a hunt for uncharted aesthetics or something like that, this is not exactly what I’m attempting to highlight in the shows I curate: the influences and intersections are in the spotlight instead.

Following up on this: are you at all interested in photographic technology? Do you have a preference regarding the equipment you use, or is the camera an efficient tool for you to achieve a desired effect?

Recently I bought a new camera with a higher resolution to have more possibilities to print large images, allowing me to present my object-subjects in 1:1 scale. I always try to preserve the original dimensions of the things I document, like in “The Process”, a series of photographs of discarded, blank photo paper used to produce standardized portraits of detainees, discovered in a photography darkroom of the “Patarei” prison in Tallinn. But answering your question: I think I relate more to the latter, my camera is a device that can help me explore a certain subject. It’s a very good tool for recording information, but what I also find fascinating is that photography is a trace in itself, a proof that I recorded something with it. And when I’m taking pictures of a spyhole or stair step, this also creates a trace and works as evidence of how those things were erased, repainted or scratched. I try to locate spaces in between those different types of trace-making and work in between them.

I wanted to ask about your audience. Your work – and as I understood from your previous interviews, where you stated that the work is welcoming a variety of interpretations, but retinal perception is only the first stage of getting acquainted with it[4] – is meant to be open-ended. Nevertheless, I’m curious whether you witnessed or heard of a reading that you weren’t expecting?

I believe that the strongest human desire is the desire to know. I leave it to the viewer to decide what they want to get from my artworks. I don’t mind if one prefers to stop at the visible qualities and rely only on visual perception. I have a very liberal approach to interpretations of my work. If the viewer wants to know more, then they need to explore the context, explaining what’s shown in the photos. And If they’re still curious, they may want to dig deeper and conduct some research of their own. It all depends on the person and I’m trying not to convince them to follow any concrete path.

So you never met with a reaction that surprised you?

Not quite: I remember showing “Surveillance”, the book containing the series with prison cell spyholes to a person from one of the institutions in Lithuania. The book contains 45 photographs, a very brief personal text, plus texts by art historians and curators. So the secretary asked me: “So what is it? There is not much text in this book! What is it about?”. And then we just started talking. Going through the images of the spy holes, she was reminded of her family story: her grandfather was sent to Siberia and went through the Gulag. Each of these images contains so many histories of both nations and individuals, and there’s much more to them aside for the visual layer and their context is very broad: the KGB, Stasi, what oppressive regimes did to people on these territories, what is happening now in the world and what will happen next.

The subject matter you work with is truly traumatic. How do you prepare to face those violent chapters of the region’s history? Did you adapt or refine your research methodology throughout the years?

The actual research part is very hard because at that stage I have to work with historical information I looked up in archives, memoirs, and notes made by people who were prisoners in these places. It’s not a thing I thought I’d do. It’s depressing and takes a huge emotional toll. But as time passed, I noticed that I’m less emotional and more pragmatic in my research. It’s a flaw in us humans, that we’re able to get used to almost everything.

In addition to my research, in my free time, when I walk around, I see different monuments with a list of names, doesn’t matter if it’s in Germany, Poland, Lithuania, or anywhere else, I’m reading all the names of people who died in this place, perished in a battle, or were tortured. Once, walking around Berlin, I found a small plaque with a list of ten women who worked in Berlin during World War II. All of them were Polish, but one name did not strike me as popular in the country. Coincidentally, it was the same surname of my tutor from the Łódź Academy of Art. I took a picture of this plaque. I made a screenshot of a pin on the map and built a digital replica of this scene using images from Google Street View and sent it to my tutor. And I was shocked when she answered that it’s a relative of hers who disappeared during the war and she and her family were not aware of what happened to her afterwards. I found out that she died during the bombing of Berlin, and finally they were able to learn the truth about her fate. This turned everything upside down in my head. You know, when you just kind of try to interpret or use some things and they respond with knowledge about another, unexpected part of reality, fact and consequential information about the world around you.

To build on what you said about facts: how do you define – again, working as both an academic and artist – the difference between artistic and academic research? Do both carry the same epistemological gravity?

I don’t have a good answer to that question, I approach the theoretical field with some ideas from my artistic practice and vice versa. I don’t think I would start to center my PhD around cross-border creative connections without acknowledging the influence coming from my work as an artist. I am not attached to this strict division between the objective and the subjective. In postmodernist deconstruction as explored by Derrida, if something is happening, for example a scientific text is published, it might be true, it might be false. Regardless, with time it becomes a platform for future things to happen. And for those future occurrences, it becomes a solid platform. Art historians write art history based on trusted sources from the past, mainly other art historians. They also talk with artists and receive some information through interviews. Some of their stories could be myths, obviously everybody has their own narrative – stemming from their individual biographies, worldview, and biases – around their own art practice. Take Robert Capa as an example. The fact that he had been photographing troops standing upright in the water, his back to the enemy’s machine guns, seems implausible. His story involving many of his images being damaged during the drying process at the “LIFE” magazine photography laboratory cannot withstand criticism as well: it was recently questioned by Allan Douglass Coleman. Still, this myth served as a platform of truth for a long time: later Steven Spielberg acknowledged the influence of Capa and his slightly out of focus, trembling images as an inspiration for the opening sequence in “Saving Private Ryan”, where he aimed to recreate the reality as depicted by Capa. Of course, when I interview artists, I try to cross-check their “testimonies” with art historians or other linked sources, but my point here is that it’s likely that everything is subjective rather than objective. And from those subjective observations we’re trying to construct an image as objective as possible.

So we assume that scientific research is also subjective.

Scientists are working in a subjective way as well. All calculations, numbers, are constructs invented and agreed upon. We believe a meter is a meter. It’s this length. Not shorter, nor longer. In the 1990s we estimated the size of the universe as 30 billion light-years in diameter. According to more recent assessments it’s 93 billion light-years. So again, a measurement is taken by subjective tools which we agree are objective. Same with academics building their theories based on texts written by their predecessors: sure, they might find and correct mistakes, rewrite, and comment, updating past views so they’re closer to this “objective” ideal. Documentary photography is not an objective recording of an event, actually, it’s infused with the subjectivity of the photographer. And what I like about art most is that it doesn’t pretend to be objective. It declares itself as subjective from the very beginning. I think that if we accept the fact that everything is subjective, it will bring us closer to objectivity.

If I understand you correctly, the only true image is an ambiguous, artistic image?

The thing with the photographic image – and there’s an irony to this – is that any photograph can become evidence now. This is not a very new thought, and it has already been used for more than ten years, in the practice of Forensic Architecture for instance. They source videos from smartphones and street cameras then combine the data into one huge piece of evidence. They gather as much subjective material as possible in order to integrate it into – not objective – but a more objective piece of information.

When I cooperated with police forensic investigators, they explained to me that for them photography is objective. It’s the actual investigation that can be unobjective, biased. And I even agree with this to some extent: philosophers – Roland Barthes being the most obvious example – have already discussed this years ago, stating that we are getting from images what we are putting into them. The favor is returned to the beholder. An image is essentially a trace of some event. It’s proof that the camera was there and then as well.

But what about AI-generated photography?

I don’t consider AI photography. Though I’m not saying it does not influence it, on the contrary, it does in a very significant way. Just this year, in November, Adobe Stock Images was accused of selling AI-generated images of a war zone posing as documentation of the Israeli-Hamas war. In reality, these images did not have any link to an existing place or a real-life situation. The status of images has changed dramatically; we have found ourselves in uncharted visual circumstances and we need to find totally new ways of interpreting them, understating them, and navigating them.

Again, coming back to this subjective-objective conundrum… We believe that photography is an objective thing since it’s a mechanical apparatus. But the person standing behind it is human, with a changing, unique perspective. They decide on the frame, angle, title… Like Roger Fenton documenting the Crimean War in 1855. He took pictures of cannonballs on the road. It was later revealed that the scene was staged, and the author moved the cannonballs from a nearby ditch for a more dramatic effect. And he titled the image as “Valley of the Shadow of Death”. The only „true” thing that the photo accounts for is that there was a man behind it at that place and moment.

You listed Derrida, Barthes, Flusser, Baudrillard as your references. Their writing is associated with postmodernism, and I was wondering if any more recent theoretical works or currents resonate with you as well.

Jacques Lacan was also an influence, but in an unexpected way: in Slovenia they applied some of his ideas to crime scene investigations. There’s a very interesting book by Henry Bond, “Lacan at the Scene” about Lacan and forensics[5]… But yes, I think that postmodernism is already outdated to some extent. Not so long ago, Object-Oriented-Ontology had a moment and I also found this thought trend stimulating. A Lithuanian theoretician and art historian, Tomas Pabedinskas, recently described my work as moving towards new materiality and sensual realism. I agree with that observation: the final outcome of my projects to date is always an “abstract” image, the stairs, tiles, plastered bullet holes are isolated, I purposefully left their context out of the frame. Nevertheless the photographs depict something very real and every time I try to highlight the material qualities of the objects documented. But yes, today we’re already post-postmodern and new theories will have to come to allow us a firmer grasp on contemporaneity.

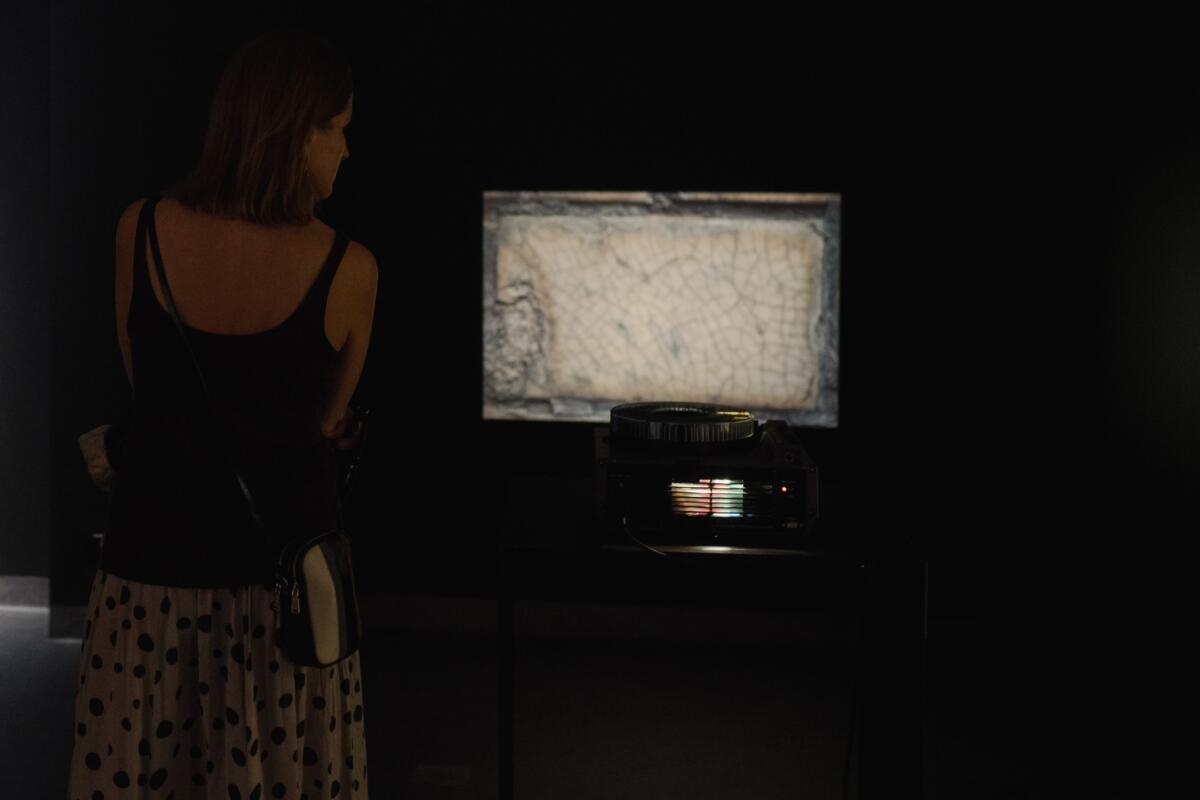

About materiality in your work: in addition to working in the medium of photography, you mentioned your installations. Could you tell me a bit more about them and how do you situate them in your practice? Your only non-photographic work I’m familiar with is “Imprint” (~2020), also on view in NOMUS. It’s an old, unplugged Samsung SyncMaster monitor, with burned out pixels visible on the screen. The barely detectable discolored patterns are images from 4 CCTV cameras placed in a shutdown detention center in Vilnius.

I rarely work with installations or ready-mades. For the show “Panoptikum” held at the walking yards of the Långholmen Prison, Stockholm, in 2021, I recreated a hopscotch field, where the final square was behind bars of the cell.

But the work you referenced also has an important photographic component: four life-sized photographic replicas of metal prison bunks. If you look closely enough you’ll notice the traces that the bodies of the detainees left on the surface of the bunks, a layer of paint has been worn out in the place the body occupied. I need to add that since “Imprint” – the actual monitor has been bought by one of the art institutions in Lithuania, so I now use its photographic 1:1 replica. So now it’s a trace mediated, an evidence of evidence.

And have you ever considered showing your work in public space?

Some festivals have shown a few of my works in larger format in the streets and the square in the park. But you know, usually people in those places are in a hurry… Maybe it’s not the best thing to place an artwork in a place where people don’t have time, will, or energy to contemplate them. And to notice the work in a non-gallery space, one has to be prepared or at least in a mood to appreciate it. There’s a lot of visual competition in public space and my works do not disclose what they actually are at first glance. Perhaps I will change my mind at some point, but now I’m not sure if it made much sense if you put one image from my series on a huge banner. Surely it would not make sense for our planet.

I’m really curious about how your practice will develop in the near future, how far you will take the notion of trace, reproduction, and mediation. Are you working on a new series at the moment?

VO: It’s a dangerous question, because if you’re working on something, maybe you shouldn’t mention it so as not to jinx it. Once, in late 2016, after I won the Debiutas 2016 Award with “Surveillance” and “PW44”, a series of photographs I made in Warsaw, showing walls of buildings with plastered holes from bullets fired during the Warsaw Uprising in 1944, I was asked where I am planning on going next to realize a new series. “The countries of former Yugoslavia” – I remember answering. I haven’t had a chance to go there yet.

But I’m starting to concretize a project linked to jewelry. This time I am not going to investigate the subjects of oppressive regimes or modes of surveillance and control, but artificial intelligence and AI-generated imagery. On December 17th in Gdańsk, during a conference accompanying my exhibition in NOMUS, I presented a paper “The Image and its Power: Interplay of Reality and Imagination in Photography”, where I spoke about Adobe Stock Images, the works of Robert Capa, Forensic Architecture, but also about rebuilding, reconstruction, and the very real, material consequences immaterial images have.

Editing: Katie Zazenski, Krzysztof Kościuczuk

[1] „ Valentyn Odnoviun. Echoes of the Unseen”, NOMUS, Gdańsk, Poland, 08.09.2023 – 28.01.2024, https://nomus.gda.pl/en/exhibitions/echoes-of-the-unseen.

[2] „Evgeniy Pavlov. Total Photography, 1990-1994.”, INTERPHOTO Festival, Białystok, Poland, 23.09.-18.10.2023, https://www.interphoto.pl/exhibitions/evgeniy-pavlov-en/.

[3] „Outsiders’s Look on Vilnius”, National Gallery of Art, Vilnius, Lithuania, 04.07. – 06.11.2023, http://www.ndg.lt/exhibitions/archive.aspx?year=2023&id=5256.

[4] „Valentyn Odnoviun. MON STUDIO SESSIONS”, Interview by Jan Gustav Fiedler, https://www.museum-of-now.com/studio-sessions-valentyn-odnoviun.

[5] Henry Bond, „Lacan at the Scene”, The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA 2012,

Imprint

| Artist | Valentyn Odnoviun |

| Exhibition | Echoes of the Unseen |

| Place / venue | NOMUS, Gdańsk |

| Dates | 08.09.2023 - 28.01.2024 |

| Curated by | Małgorzata Taraszkiewicz-Zwolicka |

| Photos | Anna Rezulak |

| Index | Ewa Borysiewicz Gdańsk Katie Zazenski Krzysztof Kościuczuk Małgorzata Taraszkiewicz-Zwolicka NOMUS Valentyn Odnoviun |