The award has already happened. The four individuals and one group that are showing at the Moravian Gallery in Brno – Robert Gabris, Jakub Jansa, Valentýna Janů, Anna Ročňová and the non-collective björnsonova – are all winners. Their prize is the financial and institutional support to make the work on show. This model, adopted in 2020, was in response to both pressure by artists, international trends – both the UK’s Turner Prize and the Oskár Čepan Award, Chalupecký’s Slovak sister, have had joint winners in recent years – and a desire from the Jindřich Chalupecký Society to better support more artists through longer-term relationships. The range of works from this year’s award – the differences and the overlaps – should still be able to tell us something about the current state of Czech art, however, even if it won’t tell us who is the best.

Who an artwork is for, or who it speaks to, might not be the most important question you can ask, but with an exhibition of new commissions, where there’s no explicit connection other than these artists are under 36 and working in the Czech Republic, it feels like it might help to draw out the distinctions, and the commonalities between the five presentations that make up this year’s Jindřich Chalupecký Award. More specifically we can ask which, if any, are addressed to the exhibition’s visitors and which might imagine and speak to a more specific audience; who is invited into the work and who is kept out.

Of the four works that use written or spoken language, three use English. For björnsonova, this might be pragmatic. Not every member in the particular grouping – six people are listed as contributors, with 27 additional collaborators – are native Czech or Slovak speakers. Their specific contributions to this installation are not made clear, but can be guessed at by comparing component parts to their other work. The book Communist Dream Glossary – of which there are several copies for visitors to read – doesn’t feel collectively authored, though it does contain multiple voices. It describes it’s process as “softwriting” – which I’d guess means working in a shared Google doc – and is a combination of very specific personal memories – descriptions of dreams, reproduced email chains and a poetic list of complaints about working in Berlin theatre – as well as cultural and political observation that draw on a specific set of theory references that would be familiar to many anglophone graduate students in the arts. The book also contains descriptions of the drawings that the installation is built around. These take the form of large pastel drawing that make up an ongoing series of Čosity (chastity) Cards. They reference, but don’t reproduce, a tarot deck: Endometriosis may be the Empress; Kathy Hacker, is described as being between the Hanged Man and Death. Visually, they reference an internationalised visual pop culture as much as the esoteric – high school notebooks and graffitied desks more than Pamela Colman Smith or Lady Frieda Harris – but its their scale and extent rather than their content that elevates the work above the adolescent. Even having 12 of a the proposed 78 cards is impressive, as is the attention to detail in the rest of the installation: the lighting, the carpentry, the coke bottles. It might be that this work is for whoever recognises their own drawings, past or present, in the cards and there’s an implicit statement, I think, that art doesn’t have to grow up. Key to this is björnsonova’s approach to non-collectivity, which might be best described as “friendship”. Friendship groups can be exclusive, of course, but there’s a sense that, for those that this work speaks to, there’s also an invitation to join.

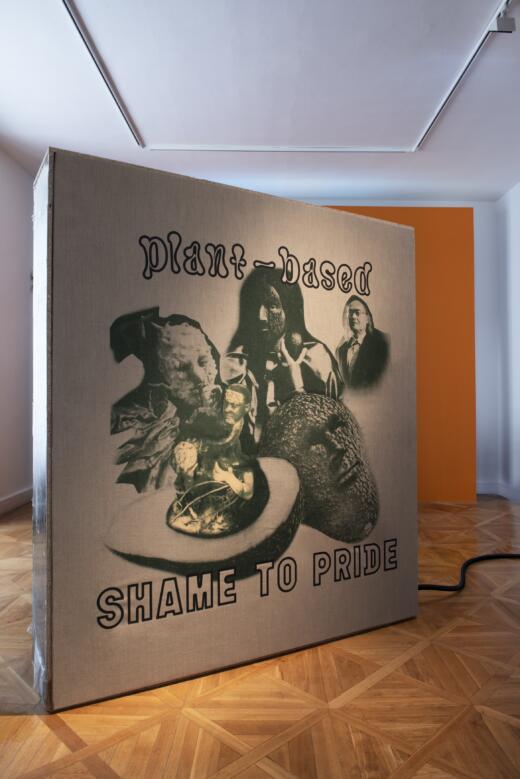

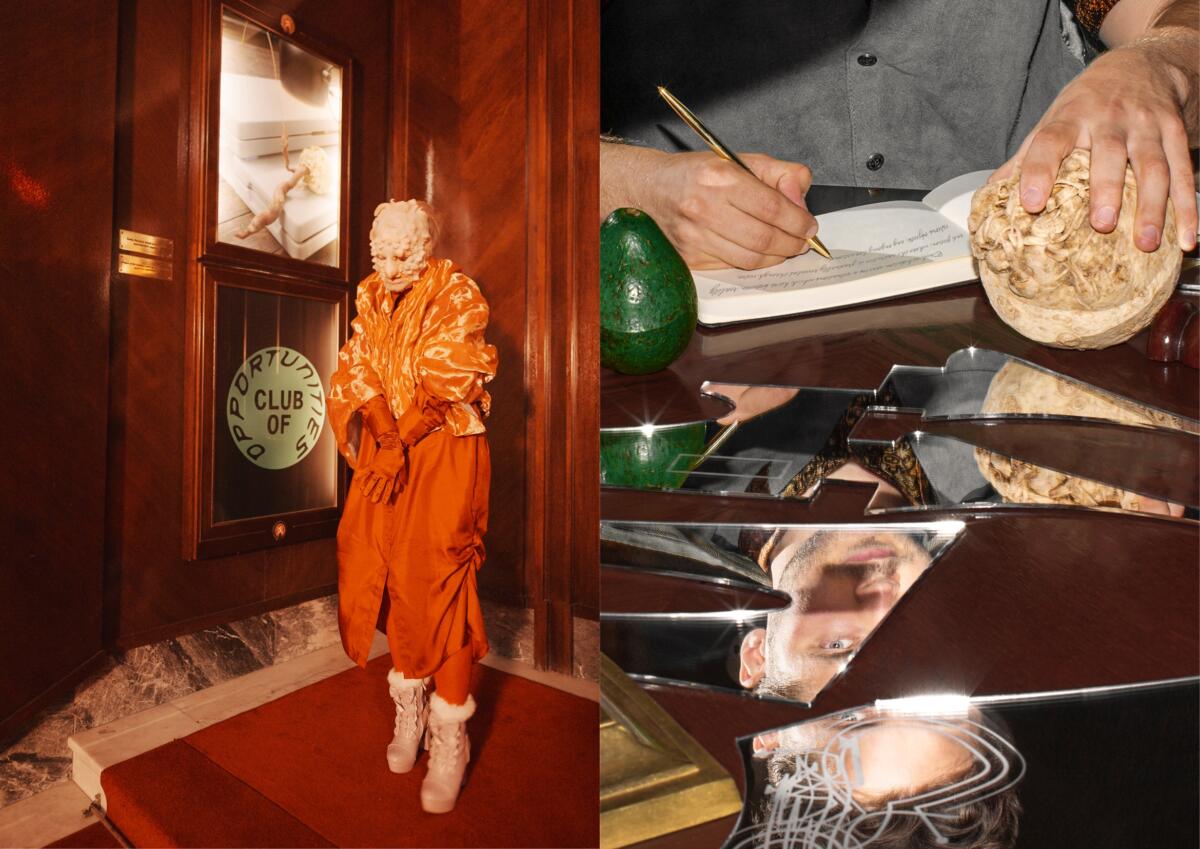

Jakub Jansa: CLUB OF OPPORTUNITIES: Episode #7 – Shame to Pride, multichannel video installation, 2021

For Jakub Jansa the choice of English as the spoken language of the film, even though he’s working with Czech actors and a script translated from Czech, seems designed to address a different audience from the one who will visit the exhibition for this work’s first outing. The video projection Shame to Pride is part seven of his Club of Opportunities series that has been exhibited in the Czech Republic and across Central and Western Europe. It follows the character of Celeriac as he tries and fails to assimilate into upper-class Avocado society. Celeriac might be a stand-in for the artist – who at a certain stage of their career can often find themselves seated in restaurants where months earlier they were serving the drinks – or equally – in the scene where Celeriac removes his avocado-green makeup – an actor. Visually the video makes multiple references – some early 20th century spiritualism, the red drapes of the Black Lodge, low budget Czech television fairy tails and perhaps a bit of Star Trek Voyager – but the Celeriac’s story is told in the style of scripted reality television, staged conversations and voice-over exposition. While the paper-thin veiling of class antagonism and the occasional direct address to the view suggest something Brechtian, it does a disservice to subtlety and sophistication with which real reality TV depicts and reproduces class, reducing structural conflicts to interpersonal ones. Celeriac’s story of class interloping doesn’t have the self-destructive drama of a Ripley or a Gatsby, and while the message of not being ashamed of our true nature — after all, you can’t smash a celeriac like you smash an avocado – might seem liberating, it’s also quite conservative. What Celeriac, and Jansa, do with their newfound self-esteem is a question for the next episode, but pride without solidarity or structural understanding is identity politics at its most reactionary.

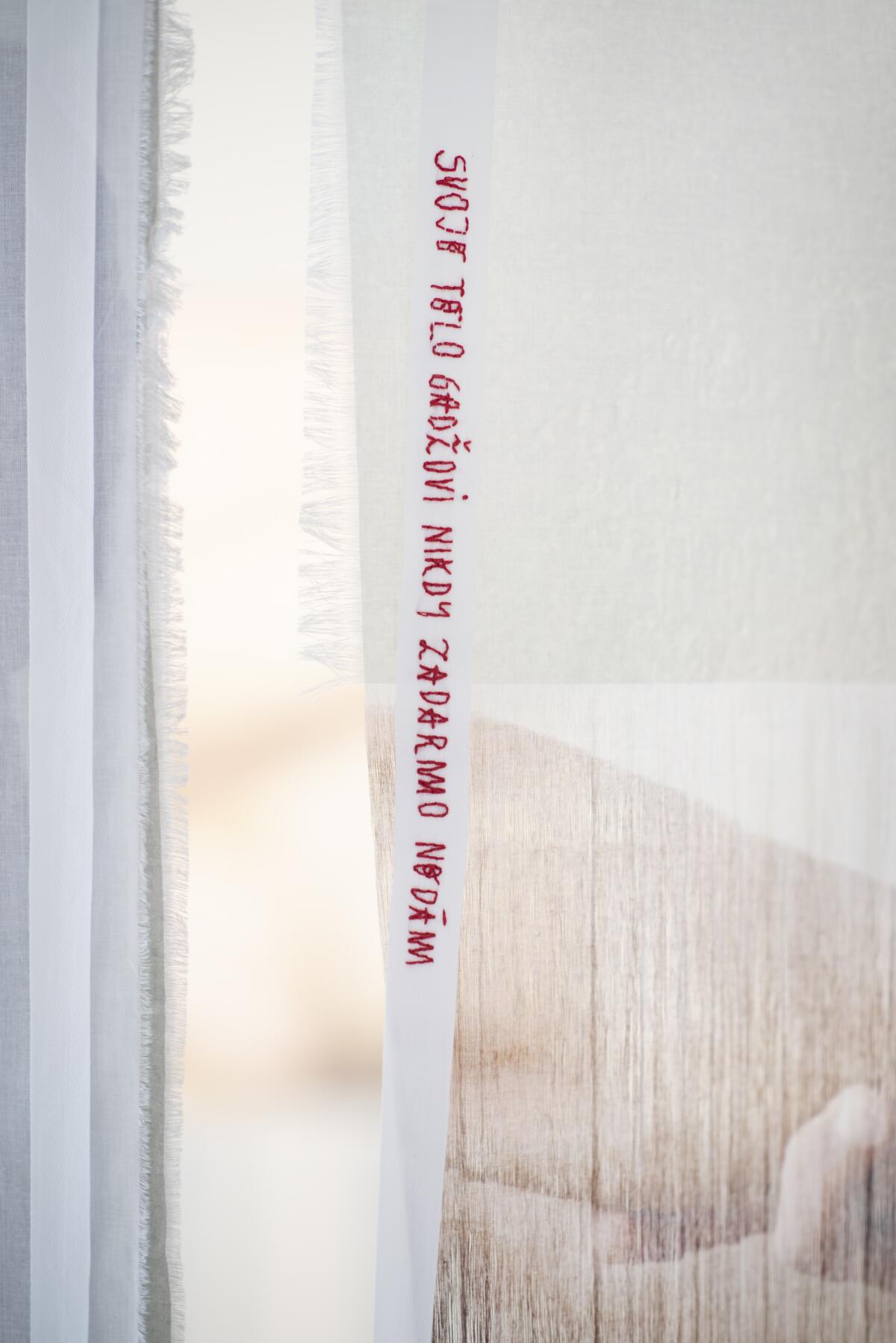

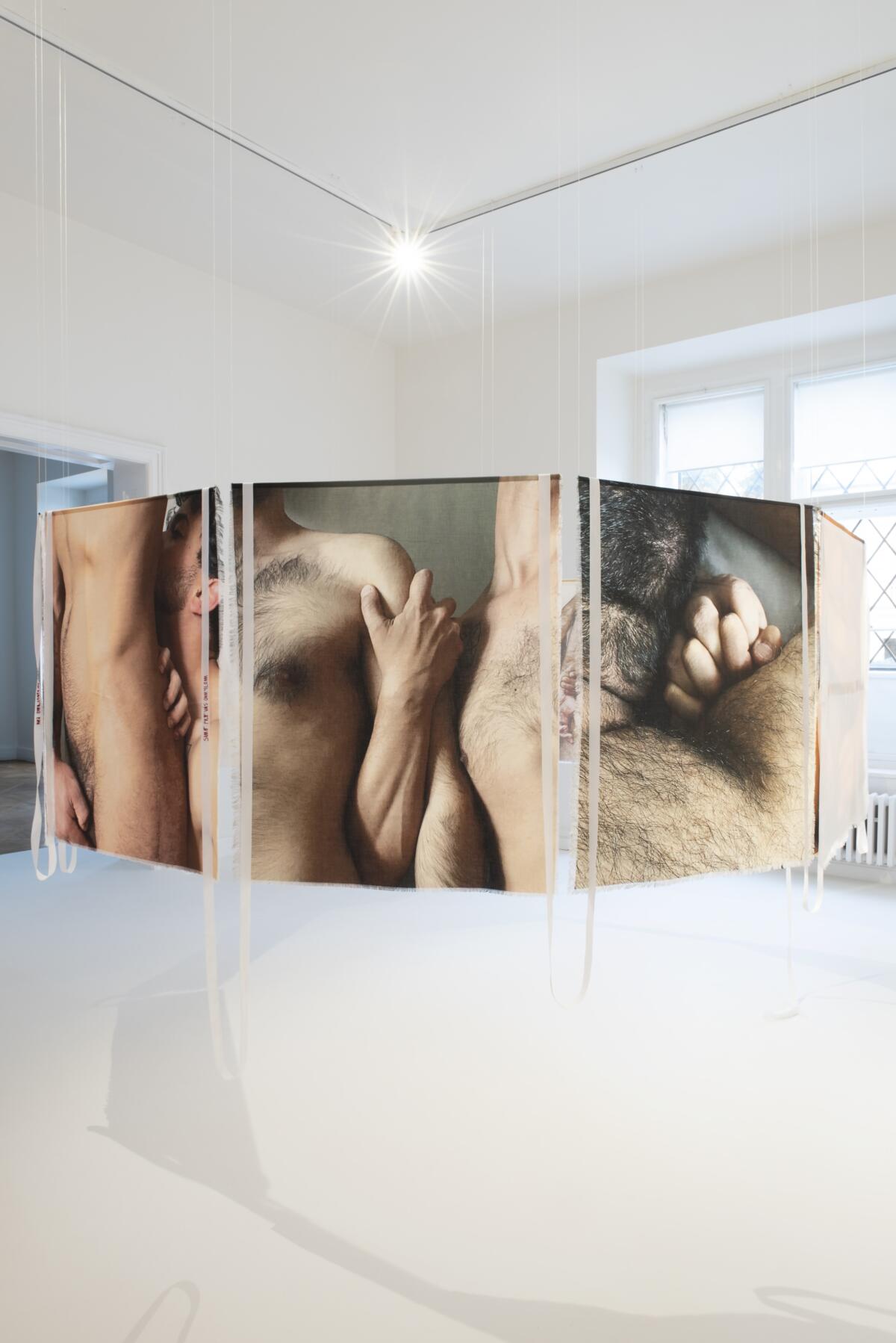

The works of Robert Gabris are the physical outcome of an ongoing project. Intimate and tender photographs are digitally printed onto fabric, then layered and unraveled, distorting and degrading the images so that they’re only partially visible to the viewer. This starting point of this work is a very specific image culture, gay dating a hookup apps that the artist use to find queer Roma men and non-binary people to participate in the project, which took place in Košice, Slovakia. While these technologies offer certain new kinds of freedom, they can also embed old prejudices, with bigotry excused as “preference”. Grindr only removed ethnicity as a filter category in 2020 “in solidarity with Black Lives Matter”. The result is a series of close-cropped double portraits that respect the subjects’ privacy, and statements, hand-embroidered and hung from the prints, that describe queer Roma experience. Here the voice is determinedly collective and confident enough that it remains untranslated from the specifically Roma Slovak language that it comes from, innovating with an almost untranslatable collective pronoun “my*” (we*). Gabris’ Vienna education perhaps provides enough distance to take the kind of pride in identity that Jansa’s work discusses, but one that is explicitly and actively disruptive to a society that denigrates and disappears it. There is translation, however, in the transition from what is an explicitly social artwork into a gallery show, and a tidiness to the works that makes me think we’re probably not being shown some of the complexity of the ongoing process. The works are a screen that selectively hide and reveal, and this is a process that Gabris has chosen to stay in full control of. Questions central to social practice – how much to show a secondary audience, how much to aestheticise what are often messy social connections, the line between participant and collaborator, how to respect privacy while giving proper credit and authorship – seem avoided by rather than resolved by the exhibited works.

Valentýna Janů’s large, single-screen video shares qualities with Jansa’s work – it’s spoken in English and subtitled in Czech, though the English here seems like the original; the space she constructs has a similar mind-palace quality – but it’s much harder to say what this video is about. A curtain pulls back to reveal a battered black disco-ball which the camera tracks across the floor in a skilfully constructed shot. What follows is a series of solo dances that could almost track a history of 20th century gender performance – cabaret, vogue, Vegas showgirl – and perhaps its sanitisation and commercialisation through pop culture; the film’s outro-music is, after all, Madonna. The words themselves are poetic and their meaning slippery – “sample sale sexy beasts salty liquid” – perhaps referring in places to a year of pandemic isolation. The narrator, who may be the moon, addresses the audience and their conditions of viewing, asking if the room we’re in should be called a cinema and the uncomfortable chairs we’re given to sit on also appear in the video, giving an expanded, more theatrical experience. In this way the film could be read – like with bjornsonova and Gabris – as an expression of the pleasure of doing and making things with other people. This is a show though, we’re here to watch, and as the credits roll we’re expected to leave.

Anna Ročnová’s is the only work in the show whose language is purely formal and material, rather than written or spoken. Natural elements – roots, branches, leaves and husks – are transformed through contact with paint, plaster, fire and synthetic fur. The question of who this work is for seems to have a more traditional answer for fine art, they are firstly for the artist herself. Material is taken from her garden and transformed by the artist alone in her studio. This doesn’t mean that they exclude a viewer, and in fact might make them the works in the show most open to personal reading. For me, it is the points of connection that are most exciting, seeing hoovered up dust grow like fungus from a log, or crude metal staples holding a dried leaf in shape. It is the human, or the cultural, details rather than the natural that grab my attention and I’m shocked looking at the catalogue images that from a distance I don’t recognise the forms at all. Ročnová’s interventions are primarily at the surface, and branches and roots remain branches and roots. Smaller, finely-crafted work hung from the wall are easier to grasp as a whole, but they also seem like they grow from the artist’s intuitive responses to the natural materials, and so the process is much more meaningful than the result. In the gallery’s courtyard, Ročnová’s cultural work is again returned to nature. Here it all but disappears, but the thread of spider’s silk between the sculptures does something that isn’t possible in the white-walled gallery; the connection of nature and culture becomes a little more reciprocal.

In previous years, there has also been an audience prize, voted for by exhibition visitors, but this year there isn’t. This is a shame, It would have been interesting to see which of the five very different ways of addressing them – open, direct, exclusive, elusive or distanced – this audience responds to best.

Czech language version of the text was originally published on artalk.cz

Imprint

| Artist | björnsonova, Robert Gabris, Jakub Jansa, Valentýna Janů, Anna Ročňová |

| Exhibition | Jindřich Chalupecký Award |

| Place / venue | Moravská galerie v Brně |

| Dates | 23. 9. 2021 – 30. 1. 2022 |

| Curated by | Jindřich Chalupecký Society Curatorial Collective (Barbora Ciprová, Veronika Čechová, Tereza Jindrová, Karina Kottová) |

| Website | www.sjch.cz/en/ |

| Index | Anna Ročňová Barbora Ciprová Björnsonova Jakub Jansa John Hill Karina Kottová Robert Gabris Tereza Jindrová Valentýna Janů Veronika Čechová |