Inside the Belly of the Beast

Agnieszka Mróz

December 2020: the three-hour-long blockade of Amazon’s gate near Wrocław causes serious delays – tens of trucks don’t leave on time. November 2020: a hundred forklift drivers gather in one section of the warehouse. They protest using horns and chant: “2,000 PLN for everyone!”. March 2020: thousands of Amazon workers in Poland, USA, Germany, and France sign a petition demanding implementation of additional protective measures. June 2019: Five thousand workers in Poland vote to strike in a referendum. April 2018: crowds protest in Berlin as Jeff Bezos receives an award for his “visionary business model.” October 2018: trade unions lead to the suspension of Amazon’s draconian system of norms. April 2017: An International Meeting of Amazon Workers from five countries is held in Poznań. March 2016: a picket against job instability and “junk contracts” at the offices of Adecco, an agency that provides services to Amazon. June 2015: as a protest strike against compulsory overtime (11.5-hour shift) is underway at Amazon Germany, a hundred pickers slow down their work by picking one product at a time, bringing the shipping department to a halt. December 2014: at 5 a.m. in a parking lot outside of the Amazon’s warehouse in Sady, several warehouse workers establish the trade union, c [Workers’ Initiative].

In December 2020, Christian Krähling, a worker at Amazon’s Bad Hersfeld warehouse (near Frankfurt), dies suddenly and much too prematurely. Krähling was the co-founder of Amazon Workers International and an unrelenting Ver.di trade union activist. It’s a great loss for the global Amazon employees’ movement. On Black Friday, the 27th of November, he picketed outside Amazon’s warehouse with the #MakeAmazonPay banner. A few days before his death, he built a snowman in front of the entrance to Amazon and dressed it in the union’s vest; he also planned to publish an international newspaper written by workers for workers from different countries, beyond boundaries. He said: “I must admit that in 2011 in Bad Hersfeld, when we began to mobilize ourselves as a group of 15-20 people, we didn’t even dream of being where we are now. Today we have an enormous, active network: organized Amazon workers, trade unions, sympathizers, journalists and artists from all over the world who work with strong commitment”[1].

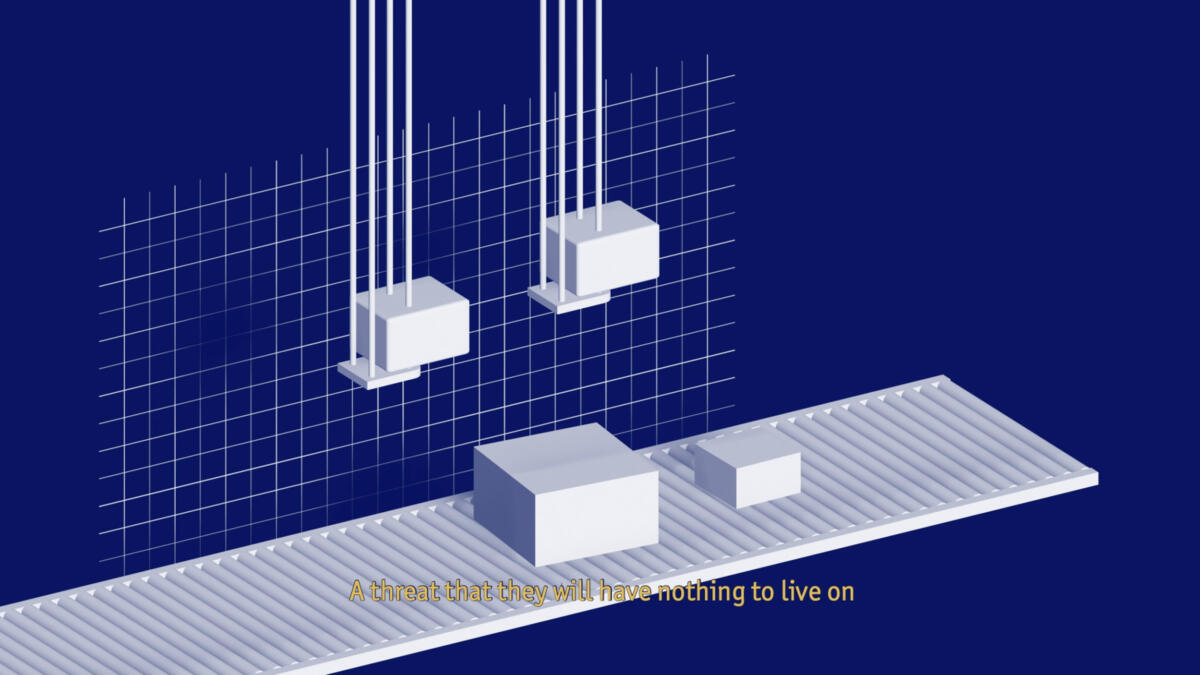

Thanks to this network – a part of which is Tytus Szabelski’s exhibition – Amazon is on everyone’s lips again. Interest I the company grew in 2020, when we – employees in the logistics sector, were classified as key workers. The public discovers that online orders are not packed by robots or sent by drones – it’s the labour of hundreds of thousands of people grouped in enormous logistic halls, who continue to work despite the COVID-19 pandemic. They carry on unloading trucks, unpacking pallets, counting cartons, pushing pallet jacks, shelving products, and packing parcels. On 16 December, 2020 Dave Clark – the right-hand man of the founder of Amazon and the wealthiest person in the world, Jeff Bezos – wrote an open letter to American institutions demanding earlier vaccination for heroes, as he calls Amazon workers. We witness the collapse of neoliberal myths about big factories and the figure of a blue-collar worker as a thing of the past.

Szabelski asks: “How to support people who fight for employee rights and, in a broader perspective, for equality and social justice?” As an organized part of the work environment our answer is as follows: portraying Amazon exclusively as a symbol of digital exploitation and workers as modern slaves doesn’t help us. We need something opposite: the recognition of power that lies in Amazon’s workforce and the support of international mobilization in warehouses. We’re convinced that unless the debates about risks of digitalization, faceless algorithms, surveillance technology, Amazon’s dominance in e-commerce, tax evasion practices, and monopolies taking over different sectors, etc. recognize the potential and strategic role played by Amazon’s workers, they will fail at bringing more justice to the world.

Amazon’s workers in warehouses in Poland, Germany, USA, Spain, Italy or France, cooperate beyond borders: they go on strike, picket, slow down their work, collect signatures for petitions, support each other on a day-to-day basis, fight for justice in courts. Despite differences in salaries, bonuses, work rate, and legal norms defining their right to strike, they are still able see the collective interest within Amazon Workers International. They look for a common, transnational platform for local struggles in logistics warehouses proliferating around the world. Workers from Poland are a part of this initiative. Since 2014, we have been members of a grassroots trade union Inicjatywa Pracownicza [Workers’ Initiative] that currently includes more than 700 workers from Szczecin, Poznań, Wrocław, Łódź, Legnica, and Sosnowiec.

We believe that Amazon’s warehouses are the key site of struggle, the results of which will not only improve our situation, but will also impact the relationship between business and labour, today and in the future. That’s why it’s such a fascinating undertaking. Amazon plays an increasingly significant part in global capital accumulation and workers from Central Europe are the key element of this process. It’s fair to say that the company itself opened new possibilities for us by becoming the hub for a truly international movement strengthened by the power of its strategic location. This movement needs many people that wish to be on the front line.

What can you do? Get a job at Amazon to build grassroots labour movement. The Covid-19 crisis has exposed our bargaining power and we have to make use of this. While employees in other sectors are losing their jobs, Amazon hails us as heroes and hires an army of people worldwide. In Poland, 18,000 people work directly for Amazon and a further few thousand are hired via employment agencies. It was impossible to replace us with robots, or relocate warehouses outside of Europe, because our job has to be done locally, near main population centres. Now is a good time to join in the action, right in the belly of the beast.

You only need to make one call to an employment agency (Adecco or Randstad) to be hired at one of Amazon’s Polish warehouses. The hiring process is conducted remotely. Free factory buses serve almost all regions of Central and Western Poland. It won’t be easy: at first, you will be offered a one-month agency contract, but if you’ll get sick or are too slow at work, it won’t be extended. It’s hard physical labour on 10.5-hour shifts, 4 days a week (or 2 days part-time), including nights. In our experience, working at Amazon (at least for a month) and organizing in a big warehouse, overcoming divisions and building relations with co-workers whom you’d probably never met otherwise, is an eye-opening, perspective-changing experience.

You can support us from the outside, but remember: Amazon workers don’t need pity, but strengthening the existing local and global initiatives. You can make financial donations, take part in blockades and protests, print and hand out flyers, engage in press and artistic activities aimed at strengthening workers’ agency, start organizing in other workplaces and share experiences.

Christian Krähling, who visited Poznań many times, used to say that when he started to organize in a small employee group in Germany a decade ago, he didn’t dream about the vocal, involved, transnational, network that we now have. We will expand and develop this network in order to win with Amazon. Get in touch and we will help you take part in the struggle.

OZZ Inicjatywa Pracownicza / Workers’ Initiative

mobile: 736 850 536 / ipamazon@wp.pl / www.ozzip.pl

[1] An interview with Christian Krähling: Common Strategy to Gain Power and Think Bigger, TSS Journal – Strike the Giant! Transnational Organization against Amazon, PDF: https://www.transnational-strike.info/wp-content/uploads/Strike-the-Giant_TSS-Journal.pdf

***

If capitalism is contagious, then an epidemic is just another business opportunity

Romuald Demidenko

One of Amazon’s leadership principles – ‘Customer obsession’ – can be reinterpreted in light of reports concerning forced efficiency and exploitation of employees who contributed to the record-breaking financial profit during the pandemic, risking their health and safety. Last year, Amazon’s logistics centres in Poland worked every day of the year. They operate according to equivalent working time, which means up to 60 working hours a week. Employees often spend many hours commuting to and from work.

Founded in 1995 as an online bookstore, Amazon is now a leading retailer setting high standards for its warehouse workers. Tytus Szabelski’s photos from the series Situational Approach, initiated in 2018, show walls of its virtually windowless logistics centres and the distinctive landscape of their surroundings. Warehouses are built on city outskirts, which sometimes means commuting is a challenge. Looking at Szabelski’s photos we can imagine the labour of thousands of people working inside throughout the pandemic, whose efforts contributed to Amazon’s record turnover while many other companies turned to working from home. Even though they agreed to work many hours without adequate protection at the height of COVID-19 infection rates, the American corporation’s employees aren’t giving up on their fight for an increase in wages. In an introduction to the AMZN project we read: “How to support people who fight for employee rights and, in a broader perspective, for equality and social justice?”.

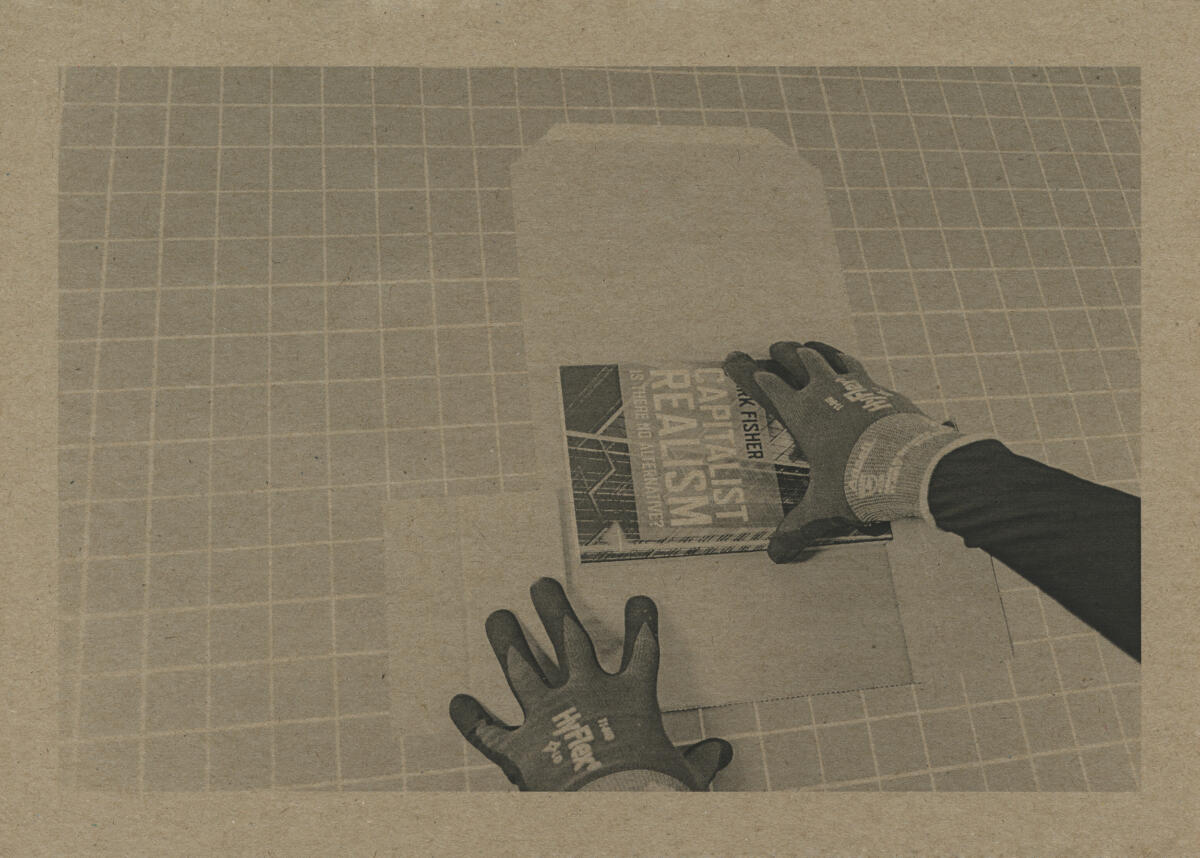

Szabelski mainly uses photography, but when it’s not enough, he seeks out different strategies and roles. To find out how work at Amazon’s warehouse really looks like, he went to work at the retailer’s logistics centre near Poznań for a month at the end of 2018, just before the peak in Christmas orders. The artist’s decision wasn’t dictated by a financial necessity, but a desire to look behind the scenes at the first Amazon warehouse established in Poland, where one of the most vocal trade unions, Inicjatywa Pracownicza [Workers’ Initiative], has been active since the beginning.

Szabelski is primarily interested in “the space of so-called ‘reality’, where it begins and ends, how we operate in it and shape it, how it shapes us.”[1] The artist’s words can be paraphrased and applied to how media coverage is shaped and how economic exploitation is normalized today. On the project’s website, alongside his interviews with workers, we can read managers’ statements. They openly say that longer workdays aimed at fulfilling more orders daily are a priority: “Like any other employer, we have our expectations of work efficiency.”[2] Szabelski rightly notes that the number of Amazon’s mentions seems to grow as fast as the company’s capital. He also reveals the secrets of a retailer that, despite facing growing criticism, maintains its positive image. Szabelski also focuses on the elements of the company’s philosophy that often remain unnoticed. The very fact that Amazon’s warehouses are called “fulfillment centers” is meaningful. Fulfilment as one of the promises made to employees features in the company’s leadership principles. Motivational quotes aiming at creating a sense of workers’ agency are displayed in common areas, corridors leading to the warehouse hall from the cloakrooms, and in the offices, from which managers supervise the packing process. They were an inspiration for the series entitled Leadership Principle, in which Szabelski creates alternative versions of corporate slogans. One of them reads: “If capitalism is like a virus, then the epidemic is just another business opportunity” (“Have an ownership attitude”, Amazon’s Leadership Principle, 2, 2020).

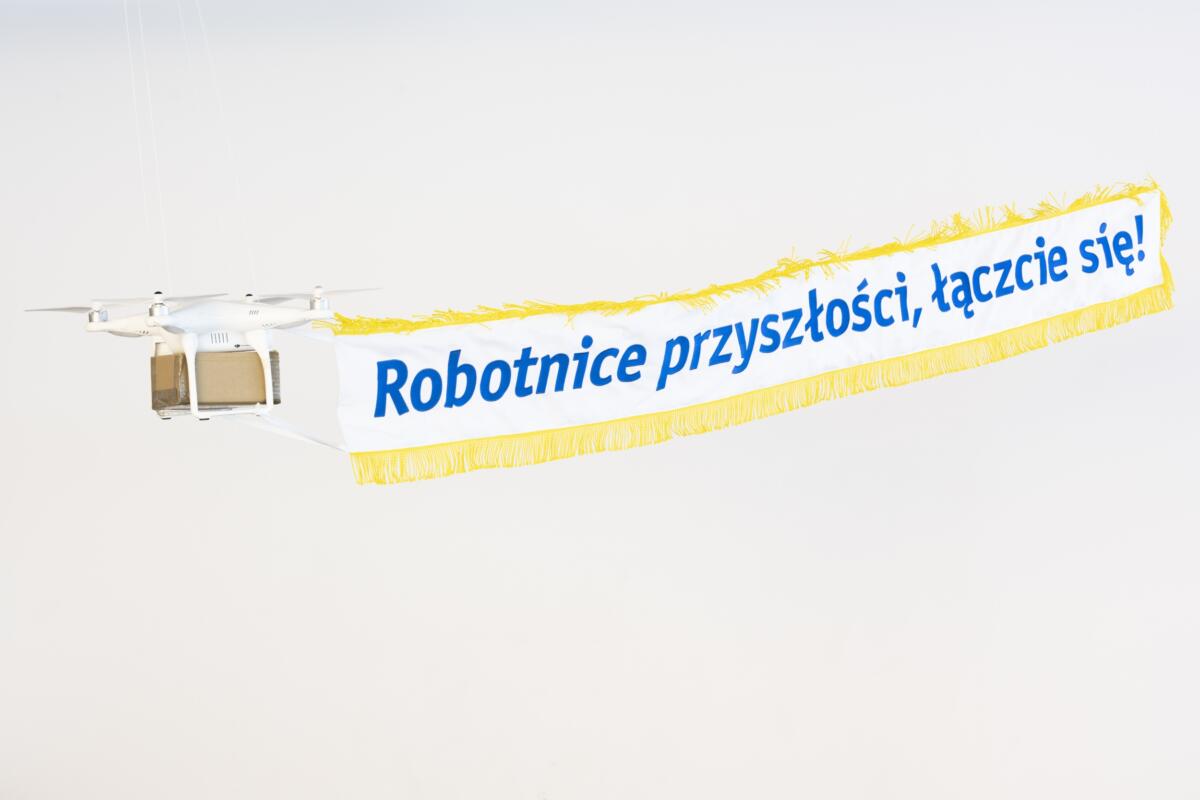

The artist shares the space of his solo show with Inicjatywa Pracownicza. This part of the project is accompanied by the famous line – “Workers of the future, unite!” embroidered on a ribbon hung from a drone in the hall that links the gallery rooms and is visible from the outside. Szabelski notices that the years-long dispute regarding malpractices could come to an end following the wave of strikes and rallies that have become especially noticeable in the past couple of months.

Another project in which Szabelski acts as an active observer is Protest Activities (2017), a series of photos from various protests, including a protest that took place in Warsaw on Polish Independence Day, which the artist attended while carrying an empty banner. As he said, it symbolized “all slogans possible to be written down or even thought about.”

The origins of the AMZN project can be traced back to Szabelski’s video entitled Television Factory (2018) set in a Special Economic Zone. We hear a voice saying: “For some time now, reality is no longer a possible type of experience.” It’s a part of the Über Fotografie essay by Bertolt Brecht, read out by a voice incorporated into a video showing a fragment of a building. The effect was achieved by holding a piece of foil removed from a television set of the same brand in front of the camera lens. The foil distorted the light and obscured the view. During the project’s presentation, the artist quoted fragments of press releases about the problems faced by employees. One of them reads: “Labour standards are strict, organization is poor, some managers use mobbing.”[3]

The artist’s work takes on the form of a photographic study, in which Szabelski exposes weaknesses of total concepts, social progress and automation. In the series entitled Forms of the Impossible (2016), he takes a closer look at architecture, for instance at the campus of Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń. He describes his observations of the campus, which is considered an icon of late Polish and European modernism. With time, its various parts have become monuments of their era. For the exhibition, Szabelski placed a fragment of a concrete wall resembling a prefabricated unit or a kind of autonomous statue in the project space. In another work, he focuses on the human impact on suburban landscape, for instance the artificial elevation of piles of rubble, dug out ground, a passage for animals above the highway that looks like a clearing or a lake whose shore was shaped as a natural beach (Reconstruction, 2014). The landscape of spaces organized and created by humans is a hallmark of late capitalism. It can be linked with the emergence of special economic zones in the suburbs.

The artist’s interests revolve around the notion of labour in late capitalism, lately a common theme of many exhibitions and publications. Here I would like to mention a newly published study Hyperemployment, concluding a last year cycle of debates and presentations in the Slovenian Aksioma Institute of Contemporary Art.[4] The term “hyperemployment” refers to the work of media theoretician Ian Bogost, who describes modern-day work and the screen as two interrelated phenomena. He provides examples of contracted work found online as part of bigger gig economy and crowdsourcing: wage labour reliant on platforms such as Uber, and inconspicuous apps that feed on our attention and impede our activities.

The AMZN project can also be interpreted as a negative image of artists’ professional life. For many years, they have been dependent on intermittent employment/precarious work (part of gig economy) that didn’t provide insurance. Their finances were contingent on on-demand commissions, they had to face the uncertainty of projects and sometimes take on paid work in different sectors. Another artistic project inspired by Amazon is worth noting here: last year’s exhibition The Fulfillment Center, organized by the nomadic Black Cube museum, which can be reported by comparisons. One reviewer suggested that artists and warehouse workers are not “on divergent paths.”[5] Izabela Pawlikowska who, during her studies at the Academy of Art in Szczecin went to work at one of the most highly automated Amazon’s warehouses, presents a different, more radical approach. This experience was the basis of her thesis at the Faculty of Painting and New Media: a series of paintings using colours typically used in the retailer’s branding. “Because of the 10.5-hour shifts and arduous commute, for most of the year we leave for work and come back when it’s dark outside, we spend our time in artificial light surrounded by yellow containers, shelves and structures,” Pawlikowska recalls.[6]

“Relentless” is a suitable word to describe Jeff Bezos, the owner of the company that not only didn’t lose much, but profited from the pandemic by using it as an opportunity to increase its turnover. It’s also a word that was initially meant to be the retailer’s original name in 1995, the year of Amazon’s founding. As it turns out, relentless.com still redirects to Amazon’s website. A decade after the company’s debut, Bezos launched the Amazon Mechanical Turk platform. Its name comes from an 18th century chess-playing device, Today AMT, referred to as “artificial artificial intelligence” by its creators, is one of the most popular websites visited by those looking for an additional job. Contractors, paid for delegated tasks they themselves find, earn approximately 2$ an hour,[7] although it’s the completion of a task rather than time that matters. Simple tasks like translating a text in Google Translate or saving photos in different file formats still require human intervention. Amazon claims that the majority of AMT’s contractors live in the US. We know that in reality they come from different countries. This could explain why they agree to work for the lowest pay, often paying the price of long hours spent in front of a computer screen and long-term depressive states.

It’s difficult to estimate how many people lost their job during the pandemic. There’s little data about a great number of small businesses operating within the informal sector, in the service industry in particular. Because of their low employment cost, employers prefer to offer workers zero hour contracts – they can terminate them at any given time and are not required to bear the costs of insurance. During the pandemic, we are witnessing a growing impact of the sectors of the economy fuelled by ghost workers working for Uber or food delivery services has become a necessity for many.

The end of the 8-hour workday has been discussed for a long time, and yet working less still doesn’t seem a possibility. We prolong our activity by sitting in confined spaces, seemingly enjoying leisure time in front of electronic devices. “Amazon is just one example, albeit very obvious and persuasive, of how our reality can soon look like”, writes Szabelski in the intro section of his project’s website. In an archival interview, Bezos unexpectedly quotes Thomas Edison: “Genius is one per cent inspiration and ninety-nine per cent perspiration.”[8] He is probably suggesting that he is the one doing the hard work. And yet today – thinking about Amazon’s army of anonymous workers – we read those words as irony. The problem is not, however, limited to Amazon – one half, or even two-thirds of the low pay, long hours labour force in Polish warehouses is supplied by temp agencies. And, as the global protests against low wages #MakeAmazonPay have shown, this is not solely a Polish problem either. Parliamentarians, who are keen to force Bezos to pay taxes, share the postulates of fair wages. The company has been evading taxes because it operates mainly as digital platform, despite the fact it employs blue-collar workers and owns delivery warehouses.

[1] Source: https://www.tytusszabelski.com, accessed: January 2021.

[2] Source: Marzena Więckowska, press secretary of Amazon Fulfillment Poland [2018], as quoted in: Adriana Rozwadowska, Znamy opinię biegłego o pracy w Amazonie: “Może powodować urazy psychologiczne i fizyczne”, „Gazeta Wyborcza”, 30.01.2018, wyborcza.pl/7,155287,22939723,krzeslo-laski-mamy-pierwszy-raport-bieglego-o-pracy-w-amazonie.html, accessed: January 2021.

[3] M. Oberlan, Firma UMC kupiła fabrykę Sharpa i ostro ruszyła z produkcją. Dla niektórych pracowników za ostro, “Nowości: Dziennik Toruński”, 29.05.2015, nowosci.com.pl/firma-umc-kupila-fabryke-sharpa-i-ostro-ruszyla-z-produkcja-dla-niektorych-pracownikow-za-ostro/ar/10843124, accessed: January 2021.

[4] Hyperemployment – Post-work, Online Labour and Automation, Aksioma Institute for Contemporary Art, Ljubljana, October 2019-October 2020, aksioma.org/hyperemployment, accessed: January 2021.

[5] Source: hyperallergic.com/539386/where-artists-and-amazon-workers-align/, accessed: January 2021.

[6] Source: I. Pawlikowska, Amazon: czy będzie strajk przeciw rządom algorytmów?, “Krytyka Polityczna”, 17.07.2019, https://krytykapolityczna.pl/kraj/w-amazonie-rzadza-algortymy/, accessed: January 2021.

[7] In a 2018 study, 3.8 million tasks performed by 2676 AMT users were analyzed. It was concluded that average earnings on the platform were 2$ an hour. Only 4% of contractors earned 7.25$, cf. A Data-Driven Analysis of Workers’’ Earnings on Amazon Mechanical Turk, arxiv.org/pdf/1712.05796.pdf, accessed: January 2021.

[8] Amazon Empire: The Rise and Reign of Jeff Bezos, directed by James Jacoby, prod. PBS, 2020, source: youtube.com/watch?v=RVVfJVj5z8s, accessed: January 2021.

Imprint

| Artist | Tytus Szabelski |

| Exhibition | AMZN |

| Place / venue | Arsenał Municipal Gallery in Poznań, Poland |

| Dates | 29 January – 28 March 2020 |

| Photos | Tytus Szabelski |

| Website | www.arsenal.art.pl |

| Index | Agnieszka Mróz Arsenal Municipal Gallery in Poznań Romuald Demidenko Tytus Szabelski |