This year Riga Photography Biennial 2020 like many other cultural events worldwide experienced unprecedented circumstances and due to pandemic, the biennials’ team together with the partners worked creatively in order to reschedule and extend the program. As a result already starting from the 29th of May Riga Photography Biennial 2020 came up with a diverse range of exhibitions, discussions, a symposium and masterclasses open to public, exploring the archaeology of reality by surveying the layers of the past, as well as the oeuvre of the contemporary digital era and its effects on our perception, cognition and image culture in general. The biennial reached its culmination in September when all the main activities took place and will continue until the 8th of November in Riga and Daugavpils. More than 60 biennial participants from 13 countries are involved, including internationally acclaimed and award-winning artists who have created work exclusively for the Riga Photography Biennial 2020. We ae offering a closer look to a few of the biennial’s exhibitions by Latvian art critic and researcher Santa Hirša.

Image as a dominant communication form of the modern day is analysed every two years by the Riga Photography Biennial, and this year its central event is the Screen Age II: Landscape international group exhibition at Riga Art Space. Exhibition curators Inga Brūvere and Marie Sjøvold have focused on digital landscapes, interpreting ‘landscape’ in a very broad sense as the material and biological environment around us and not in its narrowest sense as a panoramic view of nature that takes the viewer’s breath away and provides an aesthetic experience. The exhibition draws attention to how ever newer technologies and their availability, usage and aesthetics change our relationship with the world around us. Do changing external forms and devices also alter the potential mental image and its likely association with our sense of the world and aesthetic needs? Or perhaps this link works in the opposite direction?

Technology has greatly expanded the geography of the world, making it physically more accessible due to Westerners’ ability to travel as well as find documentary evidence about almost any corner of the globe in just a few clicks and without even leaving the house. While virtual accessibility has not diminished people’s desire to go outside, enjoy their surroundings and gain new impressions, the presence of screens has intensified this relationship, often acting as an important mediator between the landscape and our perception of it, or as a means of sharing it. Although it is probably too early to judge how this constant ‘living inside our phones’ has changed the way our senses perceive the environment, the image of landscape has become flatter in our minds, and this aesthetic of ‘flatness’ is also conveyed by the Screen Age II: Landscape exhibition.

The exhibition does not glorify technological progress, and, even more so, it does not pander to black-and-white evaluative categories. Instead, it seeks new ways to look at the technological encounters that we are accustomed to calling ‘natural’ and makes us rethink the essence of this distinction. The exhibition subjects the notions of image and landscape to self-reflection and tries to ascertain their interaction as well as capture the experience offered to viewers by the latest technological opportunities, because most of the time this is something we pay little attention to. Yet this search for new possibilities and the expansion of boundaries is not a self-serving demonstration of abilities and options, and the works of art exhibited in this exhibition have arisen from the need to identify the emergence of new artistic content in forms that have not been feasible before. For example, the witty work EXHIBIT_ONSCROLL (on view) by Estonian artist duo Kristina Õllek and Kert Viiart initially placed landscape in the time-space of Instagram and then applied this form to ‘real’ video objects, thus demonstrating how technology and social networks are more than just a ‘screen’ and a content delivery platform; they are also a man-made, somewhat autonomous landscape with its own rules and viewpoints.

The sound-landscape installation Person of Interest by Sveinn Fannar Jóhannsson, featuring his conversations with clairvoyants about found photographs, is completely different from all the other artwork in terms of its physical appearance. It comes across as an ironically profound return to analogue photography in which it is easy to list all the visible elements in an image and the associations elicited by them whilst ‘replacing’ the actual image with sound and compelling the viewer to visualise it instead. On the one hand, this work sets itself apart from the saturation of images in the digital age whilst simultaneously illustrating ways in which we think about and perceive images. At times, the clairvoyants’ remarks sound amusingly naïve, but at other times they would be a perfect match for any contemporary art exhibition guide (‘we use images to better understand the world around us’). The artist refers to this image-soundscape as the point zero of photography, and it signifies a return to the notion of image in its pure form, exclusive of materialisation. But perhaps such textual images or thought photographs could be the ultimate image form that will exist? Meanwhile, the amalgamation of opposites is apt – clairvoyants working with the ‘invisible’ and photography as an art form that makes the invisible visible.

Digital technologies tempt users to transmute image as a document or fixation of reality, and the Riga Art Space exhibition hall is filled with such transmutations, as is our everyday life, which we broadcast via Instagram filters, to name just one. Although Screen Age II: Landscape focuses on technologically more complex opportunities for transformation and tools for constructing artistic realities, reality has never truthfully existed in analogue images, painting or works of graphic art, because it has always been subject to the possibilities afforded by observation and presentation technologies. We are reminded of this by Eva Stenram’s work, in which pornographic photographs taken in the woods have been ‘retouched’ by removing the naked bodies and leaving behind vague marks of censorship that resemble scars on human skin.

In the digital screen age, we are no longer interested in the documentation of a realistic and authentic landscape, which has become so self-evidently simple to anyone who can handle a smartphone. Alienated sterility and frostiness permeate the interior and natural landscapes presented in this exhibition (it seems that at least three works depict mountain views or elevated clouds), and perhaps it is this sterility and apparent technological rationality that incites us as users to seek out elements of chance, something unauthorised and uncontrollable, even wild – such as, for example, involving clairvoyants in our image experience or transforming a traditional landscape into numeral animation. Tuomo Rainio’s work, which is based on binary codes, reduces landscape clichés to the basic elements of the digital world and focuses on what forms the basis of any image regardless of technology – all images are a collection of various visual forms, and each form is made up of small dots that create colours, lines and strokes.

If the exhibition were to be perceived as a symbolic portrait of the modern landscape, then it would be best described by the word ‘split’, and this split is emphasised by almost every work of art included in it. The prototype of the 21st-century landscape is not a panoramically wide and seamless view but a multi-channel flow of images on individual screens or a pixelated blur of visual forms. This fragmentation reminds me of my own hectic use of internet technologies, using multiple tabs and sites at the same time, scrolling up and down through the apps on my phone, going back and forth. I think that this polyphony, this parallelism, is familiar to all of us.

As an event, the exhibition focuses on topics and authors that usually reach the Latvian intellectual space with great delay and in a fragmentary manner. Even if viewers are not interested in the topics it offers, I recommend visiting the exhibition, if only to see work by world-renowned and sought-after artists and to widen one’s understanding about the possibilities of visual art in the post-medium age. The selection of works is well thought out, and they speak for themselves, forming a dialogue and seemingly reinforcing each other. For example, the digital romanticism of Mārtiņš Ratniks has been vividly highlighted by the concept of this exhibition, more so than if it were exhibited alone.

The topics covered in the exhibition may be too unfamiliar to most viewers, and, without the accompanying exhibition catalogue, they could be difficult to understand and fully appreciate. Here, however, it would have been useful to present the accompanying text as an annotation next to each work, because it is not convenient to leaf through the exhibition catalogue in a semi-dark room. And to anyone wishing to contend that a work of art should be effective even without a textual explanation, I would like to counter that, for many decades now, contemporary art has been closely connected to the intellectual space organised by ideas, theories and text-based knowledge. The programme of the Riga Photography Biennial is closely related to the analytical exploration of the surrounding world in art, and we are still desperately lacking in the development of intellectual (rather than decoratively impressive or emotionally moving) art traditions in Latvia.

Visibilities and invisibilities have been represented in other exhibitions of the Riga Photography Biennial, for example, in the (In)Visible Authors urban intervention curated by Šelda Puķīte. As part of this project, work by female photographers from the beginning of the 20th century, which has until now largely remained invisible to the public (and to the cultural environment), is exhibited at public transport stops in Riga. Not only is this an important attempt to actualise a hitherto undeservedly excluded episode in Latvian art history, but its format is also noteworthy, as it allows for the work to be encountered outside of exhibition halls and in places where female characters are usually presented only to sell something. A similar interplay between the ideas of feminism and space can be observed in another exhibition curated by Puķīte, namely, Postcards from Mooste by Ingrīda Pičukāne, which has been conspiratorially exhibited at the Bolderāja cultural bar. In this series, Pičukāne indulges in ironic body positivism as self-therapy whilst at the same time deconstructing the usual ways in which the female body is positioned and circulates in the imagery of mass culture.

Both projects curated by Puķīte playfully assess the relationship between women and public space by critically examining both art history, which has remained a hierarchically construed space, and advertising culture, which shapes our everyday image experience with its ‘sex sells’ message and continues to influence our self-awareness and relationship with our own body as well as the bodies of other people. These themes are still a recognised taboo in Latvian contemporary art and must prove their right to exist – addressing feminist perspectives in art is still often viewed with scepticism by professionals here, while elsewhere in the world it already risks becoming a thematic cliché. A conceptual interplay of image and space was also present in Puķīte’s Wunderkammer exhibition at the Latvian Museum of Photography, which focused on the multidimensionality of the phenomenon of collecting in contemporary art.

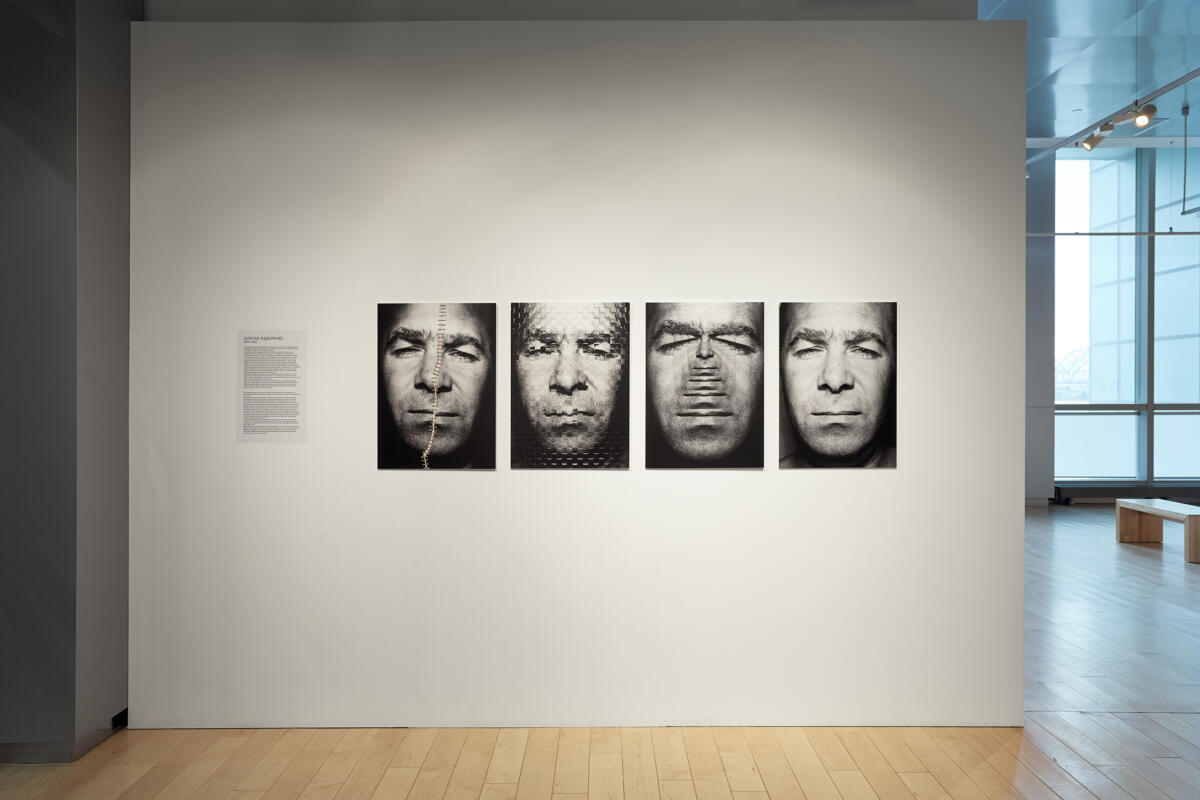

One of the conceptually most radical interpretations of the photographic image is presented in the On Photographic Beings exhibition (Latvian National Museum of Art) curated by Paulius Petraitis, which critically examines the assumption of the camera’s power over its depicted objects and the passivity of objects in front of the photographer. The objects on display can be defined as spatial photographs because they have been created in accordance with the basic principles of the technological process of photography and are formed around such traditional characteristics of photography as reflection, reproduction, documentation and duplicates. These features are applied to creating spatial objects, manifesting the idea of photography as an independent medium, a way of thinking that not only imitates other image-making practices but also with its own inner regularity acts as a starting point in the structure of works created in spatial media. This self-reflection of photography is a vital tool for navigating today’s increasingly complex world, where photography has long become more than just a passive tool for documentation.

***

The Riga Photography Biennial is an international contemporary art event focusing on the analysis of visual culture and artistic representation. The biennial covers issues ranging from cultural theory to current socio-political processes in the Baltics and the wider European region. Using the format of an art festival, the Riga Photography Biennial attempts to record changes taking place all over the world and invites us to collectively interpret them – something we not only need to see but also imagine whilst translating the complicated and oversaturated contemporary visual language into meaningful relationships between our daily reality, the camera lens, historical material, contemporary art, technologies and the future. The first Riga Photography Biennial took place in April 2016.

Imprint

| Artist | Evy Jokhova, Ode de Kort, Tom Lovelace, Andrés Galeano, Flo Kasearu, Margit Lõhmus, Visvaldas Morkevičius, Jaanus Samma, Joachim Schmid, Iiu Susiraja, Diāna Tamane, Rvīns Varde, Richard Alexandersson, Maren Dagny Juell, Santa France, Sveinn Fannar Jóhannsson, Kristina Ollek & Kert Viiart, Tuomo Rainio, Mārtiņš Ratniks, Eva Stenram, Emilija Škarnulytė, Antonija Heniņa, Minna Kaktiņa, Lūcija Alutis-Kreicberga, Emīlija Mergupe, Marta Pļaviņa, Ērika Zariņa |

| Exhibition | Riga Photography Biennial 2020 |

| Place / venue | Riga, Latvia |

| Website | www.rpbiennial.com |

| Index | Eva Stenram Inga Brūvere Ingrīda Pičukāne Kristina Õllek & Kert Viiart Marie Sjøvold Mārtiņš Ratniks Paulius Petraitis Riga Photography Biennial Santa Hirša Šelda Puķīte Sveinn Fannar Jóhannsson Tuomo Rainio |