I Can’t Work Like This: A New Reader Exploring Recent Examples of Boycotting in the Art World(s)

As artists and curators, we often think about when and under what circumstances it becomes ethically necessary to boycott. This is the subject of a new book edited by Joanna Warsza, together with participants in her Salzburg International Summer Academy of Fine Arts seminar, entitled I Can’t Work Like This (2017). The book is packed with source materials written by artists, curators and critics, published by the venerable Sternberg Press. Coming in at over 300 pages, it presents four primary case studies: 13th Istanbul Biennale (2013), Manifesta 10 (2014) in St. Petersburg, 19th Biennale of Sydney (2014), and 31st São Paulo Biennale (2014). The book examines social issues that have been critical for artists in recent times, ranging from the marginalization of LGBTQ communities, to for-profit detention centers for migrants, to calls against gentrification within urban cities, presenting these as case studies destined to help artists and curators who are often forced to confront rapidly changing political developments, who sometimes must ask themselves: should I stay, or should I go?

The impetus behind the reader was borne from Warsza’s personal experience as curator of public programs during Manifesta 10 (M10), held in St. Petersburg in 2014. Notoriously censorious, the Russian government under Putin has time and again created difficult conditions for artists and journalists. However, when it was first announced by Kasper König that St. Petersburg was to serve as host location for M10, a petition was launched soon thereafter by curator and critic Noel Kelly, who asked organizers “to reconsider St. Petersburg as the next location” in response to recent bill that had been passed in Russia earlier that year, banning the propaganda of non-traditional sexual orientation towards minors, which critics had argued was a thinly veiled attempt at instituting official government-sanctioned homophobia into law. This new law was seen by many in the international press as unfairly targeting queers and sexual minorities. The petition to boycott M10 in response was signed by over 2,000 people. Yet following the petition a statement was released by organizers of M10, arguing that the m10 should not bear the brunt of the public outcry over this new legislation and that leaving or boycotting Russia would amount to a very slippery slope. In the end, Warsza and the Biennale considered it important to remain in Russia, rather than leave, with König stressing in a statement that it was the Manifesta’s responsibility to remain if for no other reason than to not isolate the country’s at risk LGBTQ.

The impetus behind the reader was borne from Warsza’s personal experience as curator of public programs during Manifesta 10 in St. Petersburg in 2014.

Soon thereafter, another crisis enveloped organizers of Manifesta 10, forcing them to respond: Russia’s annexation of Crimea, which eventually led the St Petersburg based collective Chto Delat to withdraw from the event in a very public way. Warsza, in response, started an internal mailing list for the public program to discuss whether to engage or disengage. The collective decision, she determined, was to stay. Situations like this—where political conditions change dramatically over the lifespan of a biennale, which often take years to plan—can be pivotal in shaping the career of participating artists and curators. As Warsza put it, “whether to go on, and if so, how?”

Another case examined in the book is that of the 13th Istanbul Biennial. When Fulya Erdemci (for many years director of SKOR | Foundation for Art and Public Domain in Amsterdam) announced her curatorial concept behind the Biennale in January 2013, the art world let out a collective gasp. In her initial statement, she said the Istanbul Biennial was to explore “the notion of the public domain as a political forum.” Yet nobody including the curator or anyone else could have predicted the prescience of this topic only a few months later, after protests erupted in Gezi Park and Taksim Square, largely a result of plans by Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan to develop an Ottoman-style mosque, military barracks, and shopping mall on the contested site.

Erdemci’s plan was to use the Biennial as a site for public and urban engagement in “rethinking freedom and equality […] in terms of spatio-economic justice.” The project was to make use of “public buildings left temporarily vacant by urban transformation,” notably Taksim and Gezi Park, which become the focus of mass demonstrations in May 2013 four months prior to the opening of the Biennial. The demonstrations that took place in Gezi touched on nationwide anti-government sentiment in response to the increasing Islamization of Turkish society, the forced displacement of millions of people as a result of the approximately 48 mega urban transformation projects in development, made any mention or activation of urban space in the country a potentially divisive and dangerous political act. At a public event held on May 10 2013, a protest by the Conceptual Art Laboratory created a public relations disaster for the Biennial team, when the group interrupted a performance by Brussels based duo Vermeir & Heiremans, repeatedly entering the stage and lying on the floor with a banner criticizing the Biennial.

This action was borne from the general disenfranchisement felt by many in the Turkish arts community, who saw her as an outsider unresponsive and unable to really grasp the complexities of urban transformation in the city. It was not long before public discontent began to mount against the Istanbul Biennial due to its funding structure, notably their close relationship to Koç Holding, an organization that was heavily criticized by local activists for their involvement in the manufacture of military supplies and significant real-estate holdings in the areas most acutely affected by gentrification in Istanbul. The subsequent protests led to waves of popular unrest, emanating from Gezi Park itself. In the end, a decision by Erdemci in August 2013 stated that the Biennial would withdraw from all planned use of public spaces—including Taksim and Gezi Park—due to the ongoing hostilities as a result of the protests.

The case of the 19th Biennale of Sydney validates the power of divestment campaigns as one possible strategy for artists in impeding large-scale art events with decidedly unethical funding structures.

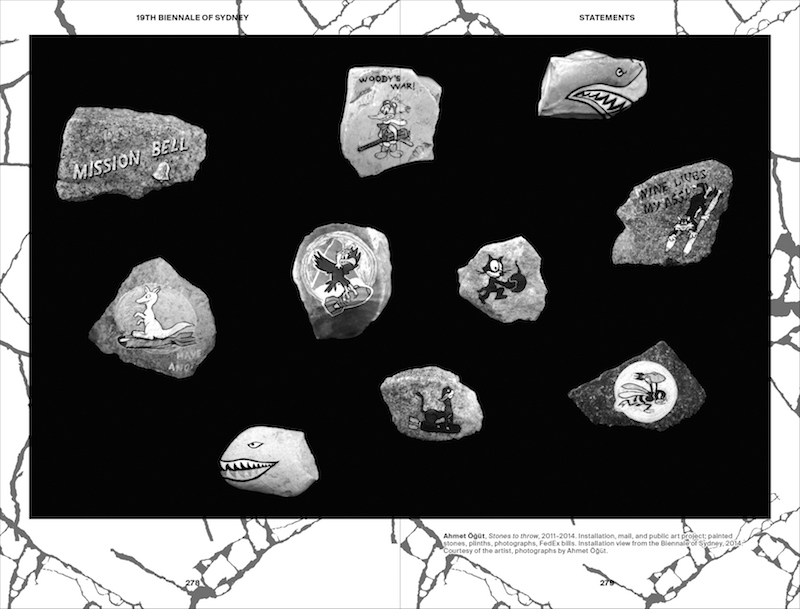

In Sydney in 2014, withdrawal became an active and “constructive” choice for five participating artists—Libia Castro, Ólafur Ólafsson, Charlie Sofo, Gabrielle de Vietri, and Ahmet Ögüt—who signed a letter in protest over Australia’s mandatory detention policy of migrants and refugees. The artists made a very public announcement that they demanded the revocation of their works and the relinquishing of their artist fees. Their letter was in response to one of the Biennale’s main sponsors, Transfield Holdings, and their contract with the Australian government to provide detention and security services for two asylum centers, one located on Manus Island in Papua New Guinea, the other in the Republic of Nauru. In response to their letter, four more artists decided to withdraw as well, including Agneiszka Polska, Sara van der Heide, Nicoline van Harskamp, and Nathan Gray. According to the letter, “We will not accept the mandatory detention of asylum seekers, because it is ethically indefensible and in breach of human rights; and […] as a network of artists, arts workers and a leading cultural organization, we do not want to be associated with these practices.” In response to the artists call for boycott, an Australian Senator, Lee Rhiannon, raised the issue in the Federal Parliament by putting forward a motion to support the artists calling for divestment from Transfield, a motion that was subsequently defeated. Nevertheless, the campaign forced the resignation of Chairman of the Sydney Biennale, Luca Belgiorno-Nettis, announcing in the process that the Biennale had also cut all ties with Transfield. After the resignation of Belgiorno-Nettis, seven of the nine boycotting artists decided to rejoin the show. The case of the 19th Biennale of Sydney validates the power of divestment campaigns as one possible strategy for artists in impeding large-scale art events with decidedly unethical funding structures.

Joanna Warsza (Ed.), I Can’t Work Like This. A Reader on Recent Boycotts and Contemporary Art. Published by Sternberg Press and Salzburg International Summer Academy of Fine Arts, 2017. Design by Krzysztof Pyda

Funding became another point of contention during the 31st São Paulo Biennale, “How to (…) things that don’t exist,” which took place between September 6 and December 7, 2014. For the first time in theSão Paulo Biennale’s history, it was to be curated by an international team that had never lived in Brazil, much less Latin America. These individuals—Charles Esche, Galit Eilat, Pablo Lafuente, Nuria Enguita Mayo and Oren Sagiv, together with two local curators brought in to bridge the local divide (Luiza Proença and Benjamin Seroussi)—advised the President of the Biennale, Luis Terepins, to not accept money from the State of Israel in response to the ongoing military occupation of Gaza and the Palestinian territories. However, in August 2014, the Biennale confirmed it had indeed received funding from Israel. In response, the curatorial team issued a statement in support of the artists after an open-letter was published addressed to the Biennale in the media, asking them to re-consider accepting funds from Israel. Ultimately, a concession was made after negotiations between the Biennale and the conscientious objectors, concluding that the funding provided by Israel would only be used to cover costs related to the projects of Israeli artists invited to participate. In this case, compromises were made through negotiations rather than an outright boycott.

I Can’t Work Like This offers an excellent, albeit brief history of recent art boycotts. It presents the recent history of activism and struggles for social justice in contemporary art in an easy to read, accessible manner, a compilation made for artists, curators and commissioning bodies interested in analyzing the sometimes toxic working conditions and unethical funding sources that can impede or even outright prevent participation in large-scale art events. The book is a must-read for anyone interested in questions around activism and art, preserving for posterity many of the primary documents detailing the political efficacy of boycotts in demanding, holding to account, literally creating a space for progressive goals and alternative, bottom up agendas in arts institutions and beyond.

Imprint

| Author | Joanna Warsza (Ed.) |

| Title | I Can’t Work Like This. A Reader on Recent Boycotts and Contemporary Art |

| Publisher | Sternberg Press, Salzburg International Summer Academy of Fine Arts |

| Published | 2017, Berlin-Salzubrg |

| Website | www.sternberg-press.com |

| Index | Joanna Warsza |