Adam Mazur: Where did your interest in art spring from?

Monika Szewczyk, director of Białystok’s[1] Arsenal Gallery: I have the impression that it didn’t ‘spring’ from anything, but that it’s a natural endowment. I come from an artistic family, so you could say I imbibed it with my mother’s milk. My parents[2] were artists, more so my father in the sense of activeness. He was a painter and a graphic artist at one and the same time and he was a real ‘aristocrat’ in both roles. One thing that certainly had a major influence on my aesthetic taste was my father’s painting… dense canvases saturated with colour in a bold, wide gesture that diminished towards the end of his life, when his heart slowed down a bit. A relish for that kind of painting has stayed with me to this day.

I grew up in my parents’ studio for the first five years of my life; we didn’t have anywhere else to live, so I had oil paints and turpentine instead of a playground. My mother painted, but she was primarily an interior designer… well, she was also extremely active in the Związek Polskich Artystów Plastyków[3]. Actually, they were both very socially active; they themselves organised and initiated all sorts of activities; for instance, they organised the Polish-Bulgarian and Polish-Hungarian open-air art gatherings in Ciechanowiec[4] and in Koprivshtitsa in Bulgaria for many years.

You can remember that?

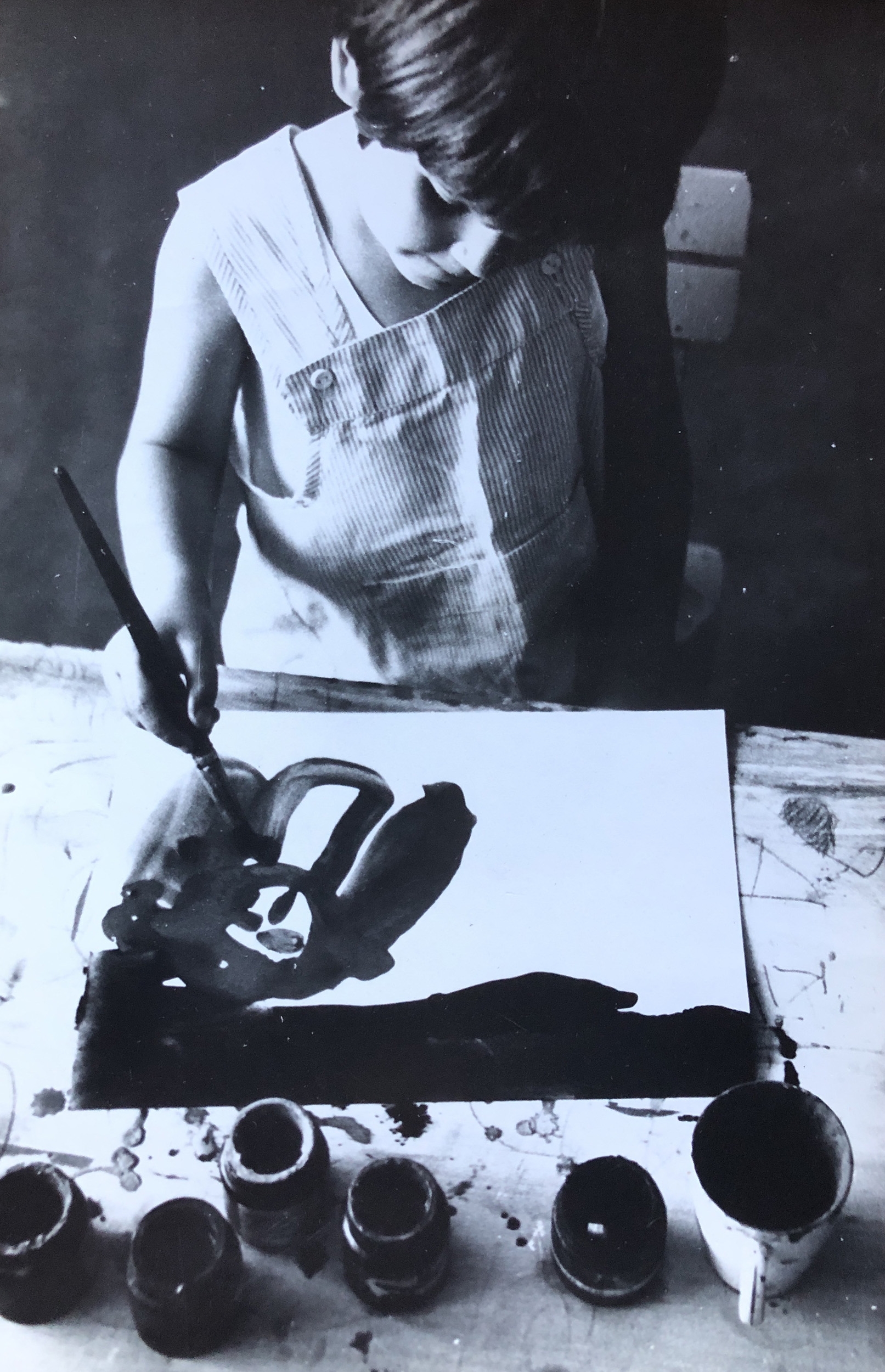

Yes, it was my childhood; my sister and I went to those gatherings. There was a family anecdote about a time in my father’s studio when he gave me a grown-up canvas and some grown-up paints, in other words, oils, and about how, as a two-year-old child ,I conquered that canvas in a way that was easily foreseen, which is to say, fairly compulsively. Because it was open house at the studio, at our home, all sorts of vernissages in Białystok ended up back at our place. The next time people from the art world congregated there, my father showed them my canvas, but presented it as his own. Oh my, those discussions about art!

At parents workshop, courtesy of Monika Szewczyk

Did you think about becoming an artist?

When I was at high school, I gave very serious thought to theatre history; I went to all sorts of theatrological talks and plays. When you have something at your fingertips, something you constantly experience as a natural part of your life, it doesn’t hold much attraction for you and you search for something more distant. If you’re a photographer’s child, you might be incapable of taking photos for ages because it seems too available to you. It wasn’t until the end, when I was in high school graduation class, that the penny suddenly dropped and I realised that I had to go for art after all. Włodzimierz Łajming[5] helped a bit with this enlightenment by persuading me to try for the Academy of Fine Arts in Gdańsk and, I started working feverishly for a brief while on ‘building a portfolio’. But if you’re a painter, then you don’t sit pondering over a portfolio. You just have one. If building a portfolio doesn’t happen out of necessity, out of a driving need to paint, but is only a condition for being accepted at an academy, then the situation becomes false. I withdrew from that very quickly.

How did your parents react to that?

My parents didn’t say a thing. Never in my life did they offer me suggestions. Once I was accepted to study history of art, my father cracked a joke; “Having our own art historian, a potential art critic in the house and about the place, now that’s a good investment!”

What did your mother do?

She was an interior architect so, fundamentally, she made a living by designing, but she also went to the open-air art gatherings; she painted a bit. Her painting was really great, but occasional, from time to time.

Did she exhibit, too?

It was a good profession. I mean, they didn’t support themselves from the sale of my father’s paintings. Let’s not delude ourselves. My father did all sorts of graphic work; he designed posters, books and other things of the sort, and Mum designed interiors for a wide range of public institutions like schools, banks and the Białystok library… In fact, that claimed a fairly major amount of her time because she was a good architect and received lots of commissions.

Have you been involved with your parents’ artistic oeuvres?

I held a posthumous exhibition for my father. When I began working at the Biuro Wystaw[6] as a junior member of the staff, he actually had a graphics exhibition there and I looked after it. There came a time after his death when we’d built a house and part of that house was a gallery space and my husband and I founded the Sławomir Chudzik Gallery, where I showed my father’s work for several years. His death was a quarter of a century ago and, since then, we’ve used his paintings once in Jakub Szczęsny’s Kolektor[7] installation, which stood in the park during our Journey to the East[8] exhibition. Jakub saw the paintings in our home and they inspired him to build the Kolektor; it was a kind of kaleidoscope, but instead of photos, you could see real paintings. Galeria Sleńdzińskich[9] in Białystok is preparing a Chudzik exhibition this year and we’re working with them on it in a family team.

What was Białystok’s artistic life like before you went off to university?

In the sixties and seventies, there was one of the many BWAs; it functioned very much like its counterparts in other cities and towns did. The stand-out features for Białystok were the Białowieża[10] open-air arts gatherings and the ones held in Hajnówka[11]. Hajnówka was focused on sculpture and furniture and Białowieża concentrated on painting and some genuinely brilliant artists attended them. We have several oil paintings by Panek[12] in the collection and oil paintings by Panek aren’t exactly a glut on the art market. He painted in oils mainly, if not solely, at the open-air gatherings in Białowieża. Nowosielski[13] also turned up at them and so did artists from abroad, because the gatherings were international. Sometimes they were very interesting and sometimes, less so. It was much the same with the exhibitions at the BWA, where the programme was both highly typical and comparable to other, similar institutions around the country. In the mid nineteen eighties, the Contemporary Art Gallery was set up; it was based on the collections of the BWA and the Białystok District Museum[14]. The gallery was a department of the museum and I was the first person to head it.

In Kyiv with Sylwia Narewska and Alvetina Kakchidze, working on ‘Our National Body’ exhibition, courtesy of Monika Szewczyk

As a young person, did you take part in that artistic life in your own right and no longer on account of your parents? Did it interest you?

Visiting galleries and museums, seeking out information about art, looking through albums, that’s nothing special, it’s normal behaviour for a person who’s into culture. I went to vernissages. A great many of them wound up at our place. There were periods when Panek lived with us for a whole week. Actually, it wasn’t just Panek; Ludwiński[15] once made himself at home at our place. For a week, he simply couldn’t leave Białystok. He set off to catch the train every day and every day he came back again. And when he returned, so did the conviviality around the table and the conversations got going again. As a child, I had a sense of the appeal of that sphere and, to be honest, that isolated me slightly from my peers. Being a child who continually spent time with adults, I often didn’t have anything to talk to other children about and encounters at school weren’t always simple because I was rather more interested in other things.

Do you think that anyone asked me a question about what I wanted to do? While I was still at the museum, I went to my director with a programme and told her that I wanted to set up a few solo exhibitions for particular names and what I heard was “All right, all right, but in five years’ time or thereabouts”. That was a clear signal that I was going to be waiting for a long time. Of course, when I moved to the Biuro Wystaw, I realised that I’d break through more quickly, that I’d be able to add my own ideas to the exercise book, that the time for change was approaching.

Did you travel to Warsaw to visit exhibitions?

Yes and in every place I visited, I searched for galleries. It was something so self-evident that it seemed to me that everybody did it… everyone goes vernissages and views exhibitions that they like to a greater or lesser extent, but which they’d never dream of missing.

It’s often the case that our own identities and interests are built in opposition to what our parents do.

We were very close. They were both fantastic and the bonds between us were extremely strong.

We’re talking about the nineteen seventies at the moment and that isn’t a period when painting was a major trend.

Right, but if you were to examine the life of a BWA in the provinces, that wasn’t necessarily terribly obvious. Jan Świdziński[16] put in an appearance here and the Znak gallery, run by Janusz Szczucki[17], was operating to a conceptual profile, but the truth is that if you were to examine the BWA’s programme, which was often based on random choices, it was painting that reigned supreme. The first director of the Białystok BWA was a painter, Mikołaj Wołkowycki; his successors sought a balance between the disciplines, which meant that fifty per cent of the exhibitions were painting and the other fifty per cent were everything else… prints, sculpture, fabrics, glass art… I’m joking… a bit… but the principles for building an exhibition plan in those days didn’t provide for profound reflection.

When did you leave to study the history of art and where did you go?

I graduated from high school and took the entrance exams to study the history of art in Lublin, at KUL[18].

Is that the only place you applied to or did you try Warsaw, as well?

Back then, you chose your HEI and went to take the entrance exams, which were held at the same time everywhere. I chose Lublin on account of my friend, Danuta Korolczuk, who was planning to study there at the Maria Curie-Skłodowska University, so that’s what dictated my choice… like most young people, I think, who don’t check what’s going on at particular HEIs. So, taking the line of least resistance and for sociable reasons, I went to Lublin to study the history of art.

Lublin’s a fairly specific environment.

The times were specific, too. It was 1980, so it was ‚Solidarity’[19] and complete change in the social space. Then came martial law[20]. At the time, KUL was an interesting university inasmuch as you met people there who couldn’t study anywhere else. It was an oasis for all the excluded, the ones who hadn’t been accepted by any other HEIs, which meant that people of very different ages, with a political background, showed up. In a sense, it was a highly interesting place. From the art history point of view, it was, perhaps, slightly on the weaker side, because I’d always known that it wasn’t the Middle Ages that would absorb me, but contemporary art… and the history of art at KUL ended with Stanisław August[21]. I hadn’t foreseen that. My thesis supervisor was Professor Ryszkiewicz[22] and when I suggested that I could write about the open-air art gatherings in Białowieża, he gave me filthy look and said, “That, young lady, is not the history of art”. He imagined I was going to write about Secession glass, which was what I’d initially intended, but we compromised and he gave me Pruszkowski’s ‘Warsaw School’[23] and the open air art gathering in Kazimierz Dolny[24] as my topic. The history of art with the emphasis on ‘history’.

In Arsenal Gallery with Andrzej Mroczek and Leon Tarasewicz, courtesy of Monika Szewczyk

Who did you meet in Lublin?

First and foremost in Lublin was Andrzej Mroczek[25]. His BWA was completely different, with a programme based on a vision primarily conceived by himself, with an awareness of the approaching changes in art, with a clear orientation towards conceptual art and a group of artists who had genuine bonds with the institution… and it made its presence felt after martial law, when all the other galleries were being boycotted by the artistic community. It was in Lublin that I became aware of the existence of Andrzej Partum[26], Gerhard Blum Kwiatkowski[27], Zbigniew Warpechowski[28] and Jurek Truszkowski[29].

How do you remember Mroczek?

When I started work at the BWA in Białystok, my boss sent me to a directors’ congress; against the backdrop of all the others, Mroczek was like an exotic animal. People were sitting around the table and talking about art as if they were discussing the potato trade. “I’ll do you a Tarasin[30], you do me a Kuskowski[31] and we’ll join forces on the transport, it’ll be easier and cheaper. Or… let’s do an exhibition that starts in Tarnów, tours to Krakow, Lublin, Białystok, Olsztyn and Gdańsk, then returns to Wałbrzych[32]”. That’s kind of how those conversations went, with everyone clustered together… and always, sitting to one side, semi-distanced, with the mysterious smile of the Cheshire Cat from Alice in Wonderland, was Mroczek. We quickly became friends.

As a student you went to galleries more than to vernissages. Didn’t you do work experience?

I went to vernissages when there was some kind of performative activity connected with them; I didn’t do work experience and I had no notion of the concept of volunteering.

Did you meet artists there? And talk to them?

I was really rather a shy person.

From an artistic family…

I was never one to make contact first.

That’s interesting, because you’re known for rapidly establishing contact with artists.

I’m determined in my commitment to work; when I make friends, it’s firmly and I don’t keep my distance, but that’s the second step and it’s the first one that I find difficult.

And your lecturers?

Contact with Woźniakowski[33], Juszczak[34] and Grabska-Wallis[35], via their monographic lectures. Małgorzata Kitowska-Łysiak[36] was Ryszkiewicz’s graduate assistant and she had classes with us for a semester, I think, or for two. She was great, an outgoing person.

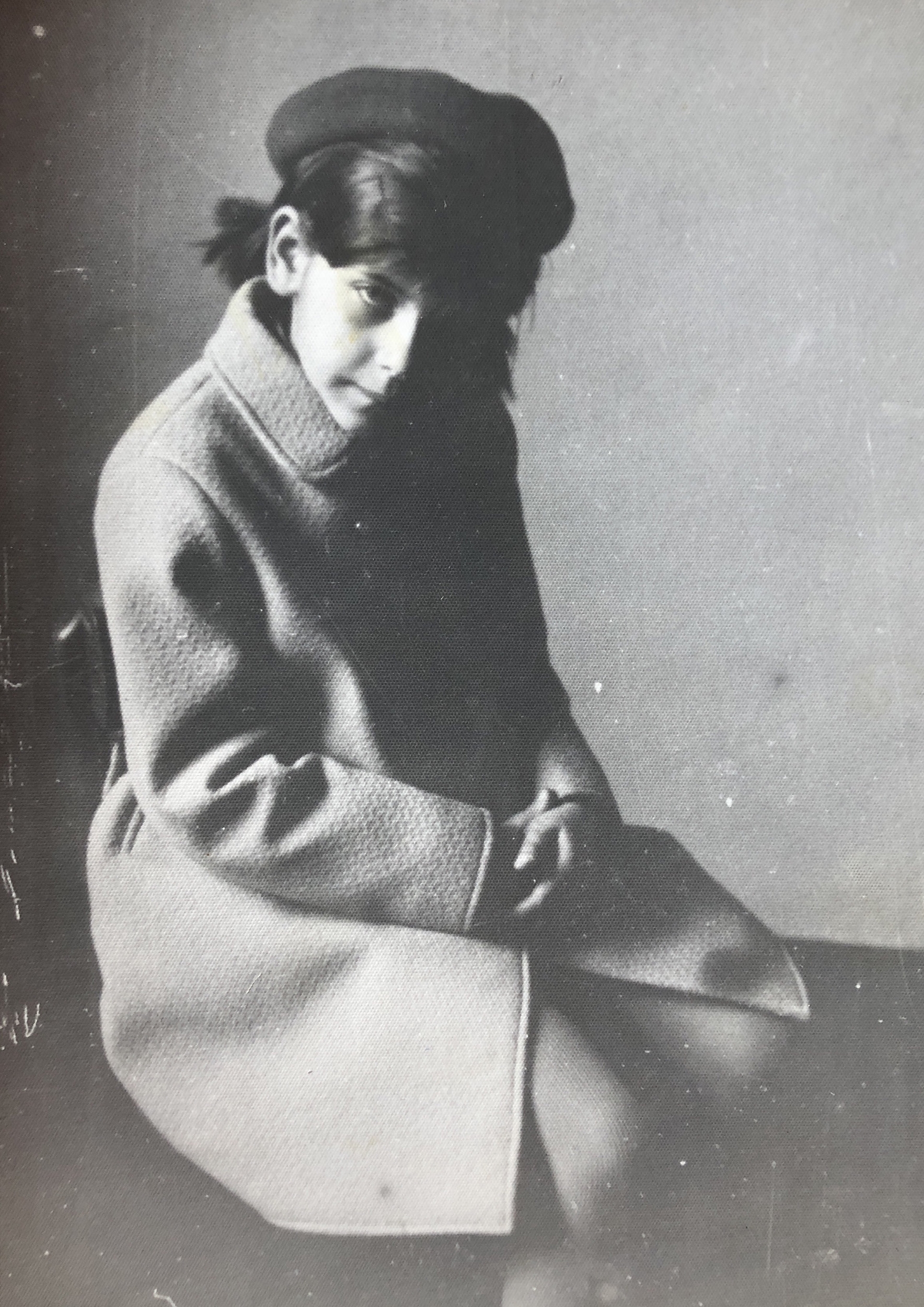

With father, Sławomir Chudzik, in Arsenal Gallery, courtesy of Monika Szewczyk

Did you also have some kind of classes about interesting art in Lublin? About ‘Zamek’? About Woźniakowski?

The curriculum didn’t step beyond the magical cut-off point of the interwar era. I don’t remember any allusions to the Zamek Group, even though it was created at the initiative of KUL students. But we knew at the time that university isn’t just about the curriculum and we were capable of finding our way to information that interested us.

You wanted to get involved with contemporary art, but how did you imagine that?

I didn’t do much imagining at all; I kind of went with the flow. Job offers appeared on the noticeboards at the university. If it had turned out that one of the offers was for a job in Książ Castle[37], I could have wound up there and got involved in I don’t know what… But somehow, I wanted to go back to Białystok, first and foremost on account of my wonderful family relationships. I was also thinking seriously about the Buiro Wystaw Artystycznych. However, an advert appeared at KUL; the Białystok District Museum was opening a contemporary art gallery as a department of the museum and was looking for someone to run it. For someone who was still a student, the proposition was a bit strange; these days, we’d be looking for a gallery director with at least five years management experience. No one would advertise a job offer like that in an HEI. But I didn’t give it a moment’s thought. It was Białystok, it was a contemporary art gallery… I went, I submitted my application and I was accepted.

Somewhere within the conversations, within the essays for the catalogue, a thread cropped up concerning playing with the exotic and the sense of being used that often accompanies curators from that region. That made me realise how crucial continuity is in terms of working together to build a partnership. Since then, there’s always been a place for art from the east in our plans; apart from numerous smaller projects, we’ve also carried out several large-scale ones like Deprivation, which was an exhibition about migration, and Attention! Border, which was crated in collaboration with Waldek Tatarczuk and Labirynt.

It’s interesting that they advertised that particular job offer in Lublin.

Although I think they advertised it everywhere they could; Gdańsk, Szczecin… Maybe there were other candidates. That I don’t know. I went to the culture department at the regional government offices. I reckon my family connections were of some significance because, after all, my parents were well-known in Białystok. On the other hand, I was straight out of university, so I had zero experience. I did a three-month internship in the museum’s art department and after those three months, I automatically became ‘Acting Head of the Contemporary Art Department’. At the time, it was located in what were dubbed ‘the saucers’, not far from Saint Roche’s Church; three rotundas, exhibition pavilions that had previously been used for harvest festivals. There was a fourth pavilion; that was a café and the other three housed exhibitions from the museum’s collection. The collection was established like this; the Biuro Wystaw handed over part of its collection, works it had purchased, to the museum so as to create a contemporary art gallery. It would’ve been really great if it weren’t for the fact that they didn’t let me do a thing. I was supposed to turn up at work for eight hours, act as a guide for tours and imagine what I might be allowed to do in the future. Finally, after a year, I ditched it.

Was it a kind of feudal structure, a matter of authority? Were they afraid you might show something too bold?

The thinking was this; ‘we’ve set up a new contemporary art gallery and it’s a beauty, let’s be glad of it and long may it be so and maybe we’ll hold an exhibition some day, but there’s no reason too at the moment…’ The choice of the works themselves was actually quite interesting; everything seemed rational apart from the fact that I spent a year reading books.

Do I understand correctly that, as a member of staff, you could formally occupy yourself with contemporary art?

I’d already done quite a lot of travelling around as a student. Andrzej Bonarski[38] held exhibitions at Norblin[39] at the time… I gave a lot of thought to whether it would be possible to hold exhibitions like that in Białystok. But the contemporary art gallery was a project that was done and dusted.

Late 1960s, courtesy of Monika Szewczyk

Did you follow the underground scene, the clandestine doings, back then?

Bonarski was a bit of a clandestine operator. When I started working at the Arsenal[40], I went from a well-paid position as a head of department to being a rank-and-file employee with a worse salary and worse terms and conditions, but with the chance of creating exhibitions. It quickly became apparent that the BWA did hold interesting exhibitions, but also that they were frequently uninteresting and that the predominant form of artist recruitment was the ‘exercise book’. An artist would come into the gallery and say “Please could you give me a date, because I’d like to have an exhibition here. I’m a professional artist, I’ve got a degree”. So you’d pull out the exercise book, see that you had a slot the following March and pencil that artist in for an exhibition. Stalemate in itself. You’d find yourself working with artists who’d come to you and you had no contact with those who might interest you, but who hadn’t turned up on the doorstep because it would never have occurred to them that they needed to get themselves pencilled into ‘a slot in the exercise book’. The real art was elsewhere, in independent galleries in Łódź, in Poznań and at the Norblin factory. That’s what I wanted for the BWA in Białystok.

Do you remember who was the director of the BWA at the time? Were there conversations about what you were going to do, about potential exhibitions?

When I signed the contract, Maria Maranda was the director. She was well-connected and she was actually in the throes of a transfer… she was moving from the BWA to become the director of the regional government’s culture department. That was in January 1987. The person Maranda had nominated to take her place was Ms Irena Dojlida, whose background had nothing at all in common with the art world; she could just as well have been appointed director of the theatre or culture centre. My direct boss, the head of programming, was a guy who was a chemical technician with party[41] backing.

Did you have a programme? Did you say that you wanted to do something?

Do you think that anyone asked me a question about what I wanted to do? While I was still at the museum, I went to my director with a programme and told her that I wanted to set up a few solo exhibitions for particular names and what I heard was “All right, all right, but in five years’ time or thereabouts”. That was a clear signal that I was going to be waiting for a long time. Of course, when I moved to the Biuro Wystaw, I realised that I’d break through more quickly, that I’d be able to add my own ideas to the exercise book, that the time for change was approaching.

What were the things you were interested in at the time?

For instance, back then, I arranged an exhibition for Iza Marcjan[42], a really interesting, local artist-weaver who’s dead now. A while ago, Michał Jachuła[43] curated an Iza Marcjan exhibition at the Arsenal, such a fine framing device… I held shows for Jacek Sempoliński[44] and Keine Neue Bieriemiennost[45] and a group exhibition, DOM, which Gruppa[46] and Małgosia Niedzielko[47] took part in. I worked on a Leon Tarasewicz[48] exhibition that had been contracted by Maranda.

Didn’t you think about leaving Lublin for somewhere other than Białystok?

I never thought that ‘elsewhere’ was essentially all that different, apart from the fact that I believe in change. But I remember a range of really interesting projects that happened in Białystok while I was still at school, like the Szajna[49] exhibition, for instance. I always found it odd that, in one and the same institution, you could hold a Szajna exhibition and then, a moment later, show painting which is obvious, of no particular calibre, has no energy whatsoever and brings nothing with it. And no one was bothered by that!

When I moved to the Biuro Wystaw, I knew that one small step at a time, I was gradually going to be able to change that institution slightly. Even without being a manager or the director, I could slowly break through with my ideas. I was never terribly assertive, I never felt all that self-assured, but I knew I could do it. During my first week at work, I suggested that the windows in the exhibition spaces shouldn’t be covered by curtains with paintings hung from them on wire, that this was a major divergence from the norm. The next exhibition was held in a clean, blank space with floor-to-ceiling partitions that covered the windows.

Neue Bieriemiennost was your first serious exhibition. How did your work with the artists shape up?

It was absolutely one of my first exhibitions. I remembered works by the group’s artists from the Norblin. At some stage, Mirek Filonik came to Białystok, which is where he hails from, and we started talking about an exhibition. I was working with artists who had totally different standards and expected something different from themselves. I was in the late stages of pregnancy at the time and that always slows a woman down a bit, but during that exhibition I was walking on air, supersonic, with the feeling that this was something fantastic, that I was recharging my batteries. The exhibition kicked me into gear workwise and gave me a sense of agency and greater independence and the motivation to accomplish more.

Opening of ‘Keine Neue Bieriemiennost’ exhibition, courtesy of Monika Szewczyk

What was shown at that exhibition?

There was Mirosław Bałka’s[50] Święty Wojciech[51], which was on display in the final room and consisted of a sculpture suspended against a paper background, a sheet of paper; beneath that, there was a pile of ash… and when the cleaning lady was doing her evening rounds, she cleaned it up… But, as you know, that ash of Mirek’s was no random accident, so things were tense at the beginning, but luckily we managed to salvage it. There was a work by Marek Kijewski[52] featuring King Zygmunt Wasa and works by Mirek Filonik[53] involving coypus in cages… his parents reared them and he happily reached for easily accessible resources.

I remember how my father came to the exhibition and couldn’t make himself leave… that’s how much he liked it. He came and he said that, to create an exhibition like that, you have to forget, to give up on everything you know about art. It was the first exhibition in Białystok that was so totally different.

You’ve also talked about how other visitors’ reactions weren’t quite as enthusiastic.

Of course, especially local artists. I suggested to the culture department that perhaps we could buy Mirosław Bałka’s Święty Wojciech… that was at the end of the nineteen eighties. Normally, it would have been the director of the BWA who made a decision like that, but we had a three-person committee that turned up from the culture department, fussed around the work and, in the end, pronounced that it couldn’t be purchased because it was already damaged… oh, that paper!… and where would that ash be kept?! It was rejected. After that exhibition, Mirek went to Berlin and when he returned he was a major artist with a flourishing career.

Now the situation’s reversed; we’ve taken a huge leap backwards and we have the feeling that our values and our achievements are under threat. The world we lived in is slowly ceasing to exist and, in the face of those changes, it’s becoming increasingly difficult to make the right decisions. We certainly have to reformat our way of working and forget about the solutions that have seemed safe and right so far. For me, superimposed on that is the kind of impotence connected with the power station, a sense of opportunities wasted. I’m finding confrontations that lack all sense harder and harder to tolerate. On the other hand, what doesn’t kill us makes us stronger […].

Was that when you had overcome yourself and go for complete contact with the artists?

Yes. That was the breakthrough moment. The artists played a pivotal role in the changes; Małgosia Niedzielko, Mirek Bałka, Filonik, Kijewski and, later on, Smoczyński[54], who took six months to answer my invitation. The natural process is for a young, junior member of staff to learn from their supervisors and older, more senior colleagues, but I wanted change in a particular sense; with the exception of the artists, I didn’t have anyone to learn from. It was in conversations with them that problems and doubts got solved, so yes, I had to overcome my shyness.

For yourself and for the institution? Did they see that things could be different?

A few things happened one after another; I was promoted, first to head of the programming department and then, on account of the fact that my boss, Ewa Cywińska, was coping with a long-term illness, I was made acting director just as the political transformation was beginning in Poland. For the regional government, the end of communism was synonymous with the end of funding for culture. There was a list of institutions destined to be closed down and we were at the top of it.

Was that when the museum pavilions were shut down?

No, the museum itself made that decision much later on. At the time of the list, the choice between two theatres, the orchestra, the museum and the BWA seemed simple; after all, exhibitions could always be held in the foyer of one of the theatres or the philharmonic building. The director was on sick leave… Despite my shyness, it was evident that I had the most determination when it came to trudging from one set of local government offices to the next and convincing them that, even in the depths of the most profound crisis and with a minimal budget, we would manage. And convince them I did, the consequences of which were perceptible for the next twenty years and, in fact, to this day… in terms of funding for institutions in Białystok, we always come more or less last.

Were your discussions with the new, democratically elected city and regional authorities based on the fact that you represented a new vision of art, a vision that corresponded to the era and the transformation?

No, absolutely not. No one was talking about programmes back then! In their minds, the BWA existed and pictures were hung on its walls and the visual arts community was happy.

Even the new authorities?

Too right. In general, I didn’t have to present any kind of programme at all… I was begging them just to permit us to operate.

In the crowd in front of the Arsenal Gallery, courtesy of Monika Szewczyk

They permitted you to operate. Was it the fact that you were bringing about change that infused you with a sense of mission and got you going on the process of educational activities?

Yes, but I didn’t discuss that with the authorities. The BWA was an organisation that was slated to disappear before long, so people weren’t exactly queuing up for the position of director and I was appointed by virtue of apathy… ‘a failing institution which certainly isn’t going to survive and, if needs must, then it’ll be easier to make a girl with no experience redundant because there’s nothing and no one behind her, she’s outside the organisational structures’. The fact that I was left in the position was the result of nothing more nor less than inertia. The support was in-house; it came from my colleagues. We were a team and even though I was the director, I felt like one of the group… I had really good, friendly relationships with everyone, I didn’t have to fight anyone for authority, they trusted me and that made the beginning easier for us.

You were the youngest person there?

Yes.

Were you in touch with Solidarity?

No.

But there were also local politics that you must have got involved in, like it or not, as part of your work on strengthening the institution. You had to somehow come to terms with all sorts of powers that be.

Luckily, the authorities displayed no interest in us. And, on the wave of the transformation, I felt that we simply had to give it everything we’d got so as to prove that we were worth investing in. That we had the ability to create a modern institution with a good programme and then everybody would understand us, accept us and start nurturing us.

Where did that powerful faith in the institution come from?

Naïvety.

What did your parents say?

They were fairly naïve people, too. It was an exceptional time. A moment of a certain social solidarity, of trust. You remember all those actors’ declarations, when they were saying ‘We’re going to be living in our own home! Join in and help!’[55] Do you think they were all acting? My parents were convinced that everything evil, everything wrong, was going to depart along with the system. Because, beyond communism, people are honest and good… back then, it didn’t sound so laughable.

The challenge was to run the Biuro Wystaw as if it were a gallery based primarily on a vision conceived by one person. Back then, we were all less focused on possessing and more on being and we were all searching for meaning in our work. Fortunately, at the gallery, there was always a powerful ethos of working with the artist and it was natural to take that as a foundation. I thought to myself that Białystok was as good a place as any other on the planet. Good art can be created and shown anywhere… and a viewing public can be found anywhere.

Now it’s difficult for me even to reconstruct the moment of such enthusiasm. But when you talk about Bonarski, for instance; at the time there were several people like that, people who took a slightly different line, who had a different idea. It may have been connected with art, but it could have followed a different course, not necessarily that of saving the BWA. A lot of the BWAs collapsed and not even a lame dog wept at their passing. Have you ever thought about how your life could have developed differently? Haven’t you had dilemmas of that kind?

I have had and I still do have, but I have them at moments when I’m very low. On the other hand, the decision to involve myself in art didn’t offer many opportunities for choice. The art market was non-existent, but even if it had existed, it’s never interested me. The challenge was to run the Biuro Wystaw as if it were a gallery based primarily on a vision conceived by one person. Back then, we were all less focused on possessing and more on being and we were all searching for meaning in our work. Fortunately, at the gallery, there was always a powerful ethos of working with the artist and it was natural to take that as a foundation. I thought to myself that Białystok was as good a place as any other on the planet. Good art can be created and shown anywhere… and a viewing public can be found anywhere.

‘Twas ever thus and thus will ever be?

My optimism faded a bit when I discovered that progress is infinite and the gallery-going public doesn’t grow geometrically relative to the efforts an institution invests in its programme, in education and in building relationships with its visitors. There comes a moment when you reach saturation point and from then on, it’s about the fight to hold onto your position.

The Arsenal Gallery’s profile is firmly bound up with the history of the art scene in Poland, with the new definition of contemporary art that emerged in the nineteen nineties. How did you absorb art at the time? Who was important to you during the watershed?

Leon Tarasewicz was a good link to reality. He has his requirements, he doesn’t negotiate. I talked to him a lot back then and he strengthened me in my conviction that there’s no room for compromise when you’re building a programme for a gallery. There’s no room for a situation where a couple of outstanding names are jumbled together with chance ones and, well, hey, that’s OK… I realised that really quickly and found myself in conflict with the local art community as a result. In no time at all, I was being censured because I was exhibiting my ‘mates’ instead of ‘genuine artists from the region’.

Mikołaj Smoczyński was another figure I saw as important and I chased him for ages. I wrote him a really painstakingly crafted letter to persuade him to come to Białystok at a time when it wasn’t a place that interested progressive artists like the BWA in Lublin did, for instance. Of course, Smoczyński didn’t reply to that letter for two years and he was one of the first people I invited. In the meantime, I held any number of exhibitions for other artists, including a major solo show for Rysiek Woźniak[56] and it seems he told Mikołaj that he’d had a brilliant exhibition in Białystok and that it’s a first-rate place. Finally, two years after my letter, Mikołaj wrote to me, apologising for his lack of response and explaining that he was now ready.

During Z. Kwiatkowski’s performance, with Buba (Małgosia Niedzielko i Ewa Zarzycka), courtesy of Monika Szewczyk

Bałka, Tarasewicz, Smoczyński. Foksal[57] contacts. Did you go to the Foksal a lot?

Of course. I went to the exhibitions. Warsaw’s an obvious destination, with all those important places. But I also went elsewhere… to the BWA in Sopot, for instance; back then, they held a performance art festival there. That’s where I met Andrzej Partum, Ewa Zarzycka[58] and Józef Robakowski[59].

When did you meet Leon Tarasewicz?

Much earlier; it was one of my first exhibitions during my first year at work. But there was also the fact that Leon was a young artist already on the threshold of a global career, but, at the same time, he was a Podlasian. My predecessor had held preliminary talks with him, but I worked on the exhibition itself. Those were my first steps.

How did you build the programme in the early nineteen nineties?

In terms of programming, I’d always wanted the BWA to be akin to independent galleries like the Wschodnia[60], for instance. I also looked for artists in that area to collaborate with. For the first twenty years of work at least, I was attached to the notion of a gallery based on a vision primarily conceived by one person and run by an iron hand, with a decidedly small horizontal hierarchy.

How did the art community in Białystok react to that?

Everyone remembered me as a little girl, as Sławek’s daughter. Some of them were my uncles or aunts. And all of a sudden, that little girl came back from Lublin and there she was deciding who’s going to have a show. The exercise book was destroyed and there was no getting yourself pencilled in any more. It was very painful. Upsetting. But not, perhaps as upsetting as people coming to the opening and seeing art that they didn’t accept, something which, to their sensibilities, was making a joke of art. Some people imagined that there’s some kind of standard for painting pictures and then, without warning, it turned out that someone’s exhibiting daubs on a huge piece of paper, a pile of ash, and calling it art?!

Of course, at the same time, that frustration and rejection is a matter of course for the avant-garde. But what you had was a municipal gallery that suddenly changed its programme dramatically and stopped being a place where locals could present their stuff. What’s more, there was nowhere else. In Warsaw, there was… still is… the Visual Artists’ Centre[61].

That was the breakthrough moment. The artists played a pivotal role in the changes; Małgosia Niedzielko, Mirek Bałka, Filonik, Kijewski and, later on, Smoczyński, who took six months to answer my invitation. The natural process is for a young, junior member of staff to learn from their supervisors and older, more senior colleagues, but I wanted change in a particular sense; with the exception of the artists, I didn’t have anyone to learn from. It was in conversations with them that problems and doubts got solved, so yes, I had to overcome my shyness.

In that respect, things are better today because there are galleries with totally different focuses in Białystok. Customs have changed, too; the top-down ‘recommendation’ to hold exhibitions of local artists, which was a kind of extortion, came to an end. I constantly thought that I’d manage to convince people that the gallery’s programme was of worth in itself. I’m not sure if I was convincing, but the resistance certainly abated. The situation of conflict persisted for a very long time and it was always rooted in the fact that local artists, or active local artists, never came to me directly with a question about compromising and introducing some kind of exception to the programme; they always went to the culture department, to the mayor, to the head of the regional government…

There was evident danger for a while, after local artists suggested that the head of the regional government placed the Arsenal Gallery and its staff at the disposal of the Związek Polskich Artystów Plastyków because they had the brilliant idea of turning the gallery into artists’ studios where they’d produce works and sell them. But in order to produce works, they needed money, so they’d like to budget to be left in place… The curious thing was this… the decision maker didn’t tell them it was an absurd, idiotic idea and then send them packing, but talked to them fairly seriously. Meetings were held; I was invited to one of them It was then that, in desperation, I took Paweł Jaskanis from the Ministry of Culture along. During the meeting, the activist presented his ideas; the head of the regional government listened patiently and I sat there like a pillar of salt because said head looked as if he was buying it. And then, without warning,, everything was decided by a few words casually uttered by Jaskanis; “Well, yes, that’s all very interesting, but it seems to me that the Arsenal Gallery has an excellent programme and it would be a pity to abandon it.”

Didn’t you enter into a comprise with the local art community?

In my opinion, I gave as much ground as I could without losing my sense of reality or ruining the programme. It didn’t seem to me that I was kind of fervently radical; it was a more a case of being afraid that I wasn’t radical enough. Nowadays, when I try to see it from a different perspective, I have the impression that maybe it was because of me that the Białystok branch of the union no longer exists and the local art community became scattered because it didn’t receive more support from the gallery as an institution. On the other hand, though, we were always more receptive to seeking out bonds with Białystok and emphasising localness.

From my point of view, you’re an exceedingly tough person who has accomplished an uncompromising programme. I see the compromises as I travel around Poland and observe exhibitions that aren’t publicised in the national media, but are simply a nod towards the local community. I don’t judge that; I simply see that it’s an attempt to work with that community. Your moment of stepping out with a programme based on the vision you conceived was important, though. The artists had to try and conquer the Arsenal. After all those agreeable open-air gatherings you mentioned earlier, the time had come for a real gallery.

Nonetheless, I felt a sense of relief when the city took it upon itself to find a new solution, something other than a shaky compromise. At a certain moment, the Sleńdzińskich Gallery appeared with a programme devoted primarily to the local art community… and it’s a municipal gallery with a budget that I think is actually higher than ours, so now the artists can’t say they haven’t got anywhere to exhibit. Our programmes don’t suck the energy out of one another, there’s an alternative, the Arsenal doesn’t have a monopoly; other institutions with their own specific character are emerging.

At home with Gerard Blum Kwiatkowski, courtesy of Monika Szewczyk

OK, so what’s the Arsenal’s specific character? What does your vision of contemporary art involve?

In my opinion, the key is extremely attentive observation. What suits me best is the obstetric curatorial model, where the curator is a companion who is focused on the artist, rather than someone trying to ‘give birth’ to the artist. Enormous mindfulness of what’s happening in art is of the essence, as is the conscious scrutiny of context and where we are. Once you decide to hold an exhibition, then it’s a very good thing to ask yourself three questions; “Why? For whom? And what do we want to achieve?” And, yes, a humble attitude, the awareness that every definition is subjected to reconstruction by art itself. Every time we think we know something about art, then art demonstrates that, actually, we don’t and that the direction it’s heading in is different from what we thought. I don’t like long-term thinking and planning… I try to ensure that our exhibition schedule changes dynamically from year to year and that it hasn’t dashed too far ahead. But the Arsenal is also shaped by its curators… or, more to the point, by its women curators.

Tell me about the major moments from the nineteen nineties, the moments that would define the Arsenal in the context of the critical art and contemporary art that emerged in Poland at that time. What, to you, was the most important event?

In the nineteen nineties, we were playing catch-up. For instance, the entire sphere of conceptual art didn’t actually appear at the BWA. It was in the nineteen nineties that Zbigniew Warpechowski[62], who was already the master for Oskar Dawicki[63], for instance, appeared on the Białystok art scene for the first time. But, at the same time, the ‚Poznań[64] installations school’, was well represented. In the early nineteen nineties, we took part in an exhibition at the Podewil[65] in Berlin; it was set up by Angelika Stepken[66]. She invited a range of Polish galleries to participate; they were mainly independent and based on visions primarily conceived by one person. The Wyspa[67] was there and there were galleries from Łódź, but I think we were the only BWA to show an exhibition of artists connected with us… Konrad Kuzyszyn[68], Leon Tarasewicz, Wojtek Łazarczyk[69], Agata Michowska[70]… That was our first exhibition abroad; there have been plenty since then, but the beginning were also crucial in terms of forging bonds with the artists. Wojtek Łazarczyk’s studio used to be dubbed ‘the travel bureau’ and we invested a great deal of effort in being that kind of bureau.

You like commissioned works. You were talking about playing catch-up, but that wasn’t about well-known stuff, it was about new works which made the programme interesting for people watching particular artists. What was most important to you in the nineteen nineties?

The nineteen nineties were also when we started shaping our collection, which I didn’t think of as a collection at all until the Arsenal’s jubilee in 2000, when I didn’t hold a new exhibition, but showed the works that I’d purchased because I had a feeling that they might vanish abroad, but ought to stay Poland. But I didn’t think of it in the category of a collection because I was programmed to a minimal programme. After that exhibition, two reviews unexpectedly came out; they were by Marek Wasilewski and Łukasz Gorczyca and what they made clear was firstly, that a collection has been established in Białystok and secondly, that it’s extremely interesting because it shows what’s actually happening in Polish art and it’s highly representative. That was a stimulus that made it possible to carry on collecting and I started thinking about it seriously. Work on it was a series of configurations of all descriptions. In total, I’ve held about thirty exhibitions of the collection. Most of them were my own work as a curator; some of them were by invited curators and artists. One outstanding example was the exhibition prepared in 2000 by Agnieszka Tarasiuk[71] for our fiftieth anniversary; another was the one created by Joanna Zielińska[72] and Daniel Rumiancew[73], which had a soupçon of irony in its view of the collection.

Only those were later exhibitions that define the moment, post-2000, when you turned towards the power station…

In my opinion, I gave as much ground as I could without losing my sense of reality or ruining the programme. It didn’t seem to me that I was kind of fervently radical; it was a more a case of being afraid that I wasn’t radical enough. Nowadays, when I try to see it from a different perspective, I have the impression that maybe it was because of me that the Białystok branch of the union no longer exists and the local art community became scattered because it didn’t receive more support from the gallery as an institution. On the other hand, though, we were always more receptive to seeking out bonds with Białystok and emphasising localness.

I’d never thought of the power station as a place where I’d hang the collection. I thought of it as a potential way of expanding the Arsenal, where we were stifling by then. There we were with any number of ideas, ready to do all sorts of things and we needed more space, a different quality. The moment came when we decided to devote one of the exhibition spaces to educational activities. That was the result of countless trips and conversations with Magda Godlewska, who was in charge of education at the Arsenal for many years. It was clear that we had to have a separate space. In effect, we weren’t holding twenty-five exhibitions a year any more… and there was a period when we did… because we necessarily had less space. The other side of the coin was our growing appetite for larger and more complex exhibitions. Then it turned out that the power company was able to assign half of its building to cultural activities, to a theatre or gallery. I found out about that during a completely chance conversation. At the time, we had a project for an Alexandre Perigot[74] exhibition which was really complex and impossible to mount at the Arsenal. He’d shown it at the Istanbul Biennial; it consisted of revolving stages where an exhibition could be mounted and thanks to the movement of the stages, which occurred as people used them by walking on them, the exhibition was mobile and, as the configurations between the works changed, so did the context. We decided to show it with works from our collection mounted on the stages, which struck me as being really interesting. Like every collection, it contains works which, together, form different collections. In Alex’s mobile installation, outwardly random juxtapositions revealed those relationships. It was a stupendously interesting exhibition and it was the first we held at the power station.

That was a period when everybody wanted to build, to extend museums. And there were European Union funds, as well…

Right, and everyone was building and we weren’t. First, I think the fervour we tried to spark in the authorities was insufficient. Second, there was too much competition from other quarters… first and foremost, from the Podlasie Opera and the Siberia Memorial Museum. Third, the building is a challenging one and the discussions with the power company are also very challenging…

Do you regret it?

I can’t. If I hadn’t decided to fight for the power station ten years ago, we wouldn’t have held exhibitions that have been pivotal for us, starting with Journey to the East. And I also think that the adaptation will occur some day; in all likelihood, not in my lifetime, though. Irrespective of our needs and expectations, the power station offers the opportunity of creating a genuinely stunning, state-of-the-art, progressive institution based on glorious, post-industrial architecture. There’s an outstanding design by WXCA[75]; it was chosen as the winner from a hundred and twenty-five entries submitted to the competition by architectural teams from all over the world. Bringing that to fruition would take us into a whole different space. The gallery genuinely needs that development, but even if it wasn’t about us, we’d still have a devastated building, off-putting, but with enormous potential, in the very centre of the city, right alongside the avenue that features in the plans for adapting Białystok. That conversion has to happen.

When did the Arsenal acquiring its collection?

From the outset; one of the first works, from 1991, I think, was a video cassette by Józef Robakowski. Back then, really, no one was buying videos for collections; in fact, no one bought them, full stop. Józef offered me eleven films on a video cassette. It was devotion to the object; if you have a four-hour video cassette, there’s no way you’re only going to store one twelve-minute film on it.

During ‘Signs of the Times’ symposium, Lwów, courtesy of Monika Szewczyk

So the programme was connected with building a collection from the very beginning and then, post-2000, it began to evolve?

In 2000, I realised that the collection of works purchased fairly spontaneously under the guidance of the heart rather than common sense, was a value that should be extended. The jubilee exhibition showed its potential. Throughout the nineteen nineties and that starvation-level budget, we’d buy two works over the course of a year and the artists were, let’s face it, very kind-hearted towards us. We always settled up with them, but they quite simply wanted some of their works to stay in Polish collections. Then there was 2005, in other words, Waldemar Dąbrowski and Signs of the Times[76], a moment we made the most of. A Zachęta association for the encouragement of fine arts was established in all the regional capitals and, in line with the Ministry of Culture’s provisions, they were separated from existing institutions. At the time, we had an excellent collection that toured the world; it would have been a crying shame not to take up the challenge. We set up a Zachęta at once in the form of an association, but as an extension of the gallery, with the participation of our staff, for a while as a personal union. I was the Chair for one or two terms of office and Kamil Kopania, a young art historian with emotional ties to the Arsenal, took over from me. From the outset, the statute and all the regulations made it clear that there is one collection being built jointly by the association and the gallery and that, ultimately, it would be owned by the Arsenal. That was one of the more sensible steps that we took. The appearance of the Signs of the Times programme meant that I could start talking to artists who had previously been beyond our financial means.

You promote a model institution… you’re active when it comes to participating in the community and networking with the directors of other institutions. That’s the impression I have. It’s the result of how you talk about exhibiting the collection, which does, after all, have to tour somewhere. It’s not entirely normal for someone that has a collection to want to show it and to be capable of persuading other people to do that, as well.

I thinks it’s very normal. Obvious. A collection is a beloved child. In its own way, it shows our entire history, it’s a reflection of our exhibition work, we don’t want to keep it in storage, from time to time it’s a real pleasure to be able to see if it still works and what other narratives can be constructed from it. It’s even more of a pleasure to bring it face to face with other people’s notions.

Do you have a purchasing committee?

Of course. But the truth is that I select the works for the collection; that’s a space I don’t share with anyone.

What would constitute the specific character of the Arsenal collection? Its relationship to the programme, the kind of narrative that would serve to show, in an institution like the power station, what the contemporary art of all those years was?

In the beginning, I approached the collection with the same flexibility that I had towards our programme, which shows certain trends in Polish art, extending, perhaps, into Eastern Europe. In my opinion, it shows the most important attitudes and phenomena. It was much the same with the collection… the works that made their way into it were those I selected because they seemed to me to be the most significant for a given time. Then we published a book about it; it was written by Iza Kopnia[77]. In the preface, she remarks that the collection is an open one, growing in various directions at one and the same time, that it has several narratives which sometimes overlap and that some of the works belong to several different thematic areas. They’re the themes that have appeared in the art of recent years… critical art, transformation, the human condition, art about art… and a crucial point here is that the art of recent years features a great many works from Central and Eastern Europe. Frequent exposition and constructing issue-oriented exhibitions on the basis of the collection means that the decisions are much easier to make when it comes to buying new works. Of course, it also contains works that were created in our gallery and works that are local in character.

In other words, you’ve never thought about the collection in the museum category or about handing it over to a museum?

No. Why can’t a gallery have a collection? We’re the Arsenal Gallery, which has a superb collection that’s always on tour and on display. We show it at the Arsenal, as well; not as a permanent exhibition, though, but in the form of issue-based exhibitions, which is more dynamic.

With Wojtek Kozłowski during the opening of ‘Bud’mo!’ exhibition in BWA Zielona Góra, courtesy of Monika Szewczyk

You mentioned education earlier… that’s your explicitly positivist feature. It’s not only about romantic work with artists, but it’s also an imperative which drives you to create a collection and show it in all kinds of configurations. What’s your thinking on education within the framework of the gallery’s programme.

It’s years of work by a wonderful team consisting of a handful of people, educators who are aware of the particular nature of the institution and are naturally inclined towards experimentation and undertaking pioneering tasks. The most recent of those is SEPPO[78] and, if I’m not mistaken we’re the only gallery in Poland using that platform. Our educational programme is based on our exhibition programme and on close collaboration with artists.

Tell me something about the toughest moments, about wavering, about the lows. How do you recall the critical moments in your long career?

I’ve talked about them on numerous occasions; I can’t stand the martyrological strand in our history.

You’re the longest serving director of a contemporary arts institution in Poland.

I’m obviously self-conscious about that fact and please put that statement in bold. The conflicts with the art community were a difficult moment for me. In general, I’m a gentle person; I don’t like causing hurt and I don’t have a critical facet. I don’t like telling someone that they’re doing something wrong; I like to be able to provide praise and support. But the Liga Polskich Rodzin[79] manipulations in connection with the Dog in Polish Art and WWW.KAŁUCKI exhibitions[80]… now that was a really powerful blow… the way art was utilised in a political battle with such premeditation and in such a fashion.

Nothing happened in the nineteen nineties, even when the programme was rather progressive?

It took me a long time to understand that it wasn’t about us at all, it wasn’t about art, it wasn’t about someone feeling affronted, it was simply that politicians need tools in order to conduct their squabbles and art lends itself to that perfectly. The truth is that art matters to a very narrow group of people; a great many people don’t know what it’s all about and not many want to give any thought to it. But at the same time, denying art the function of creating culture, society and national identity, well, that can’t be done… and we can go on playing that tune for all eternity. We were used… and extremely cynically, at that… and the people doing the using never batted an eyelid. We ought to forget it and never look back on it again, because it’s lamentable and unsavoury. And we could do that if it weren’t for the fact that the threat hasn’t disappeared… we know that a new situation will pop up before long and the politicians will start trying to use us as a football again.

If you’re a photographer’s child, you might be incapable of taking photos for ages because it seems too available to you. It wasn’t until the end, when I was in high school graduation class, that the penny suddenly dropped and I realised that I had to go for art after all.

But you survived it and, thanks to that, your position on the contemporary art scene in Poland became even more vital.

That doesn’t change the sense of utter embarrassment connected with those events.

In late 2019, your job hung by a thread for a while. You won the competition[81]. So what now?

It’s a tricky moment because these are difficult times; I think we all have a sense of an unavoidable ending, of the need for change both globally and locally. We’re all operating in a reality which we find seriously unsatisfactory. I have a feeling that things have been better. For instance, I miss the sense of a certain pride in the changes which have come about around contemporary art in Poland over the past twenty years. Really competent people started running the institutions. Polish art became visible in the international arena. But standards are changing and we’re discussing them. On the whole, we’re unhappy during these discussions, but we have to say that we’ve managed to do a lot. When I talked to people from institutions in the Czech Republic or in Eastern Europe, everyone was impressed by the changes that had come about here. Now the situation’s reversed; we’ve taken a huge leap backwards and we have the feeling that our values and our achievements are under threat. The world we lived in is slowly ceasing to exist and, in the face of those changes, it’s becoming increasingly difficult to make the right decisions. We certainly have to reformat our way of working and forget about the solutions that have seemed safe and right so far. For me, superimposed on that is the kind of impotence connected with the power station, a sense of opportunities wasted. I’m finding confrontations that lack all sense harder and harder to tolerate. On the other hand, what doesn’t kill us makes us stronger; I think it’s time for major changes, not only in our institutions, but changes in the world and we’re somehow going to have to embrace them and put a name to them. In military terminology… and we are, after all, always engaged in some kind of war… it’s called a change of order and that’s precisely what we’re preparing for.

After the opening of ‘Agent Absurd’ exhibition at GG in Belfast, with Agata Michowska i Tomek Mróz, courtesy of Monika Szewczyk

I think that a really important moment in your history was when the Arsenal Gallery went from being forgotten even in its immediate vicinity to being recognised on a nationwide scale. In my interpretation, the scandals that embarrass you somewhat strengthened the gallery’s position and yours, as the author of the programme. You’re expanding in ever-widening circles with your exhibitions and research into the field of art. How was the Arsenal’s specific international programme born?

Focusing on artists and on what’s needed in order to work with them and create the best possible conditions for them bore fruit in an interest in taking part in various exhibitions abroad. In the late nineteen eighties, an exhibition abroad was something most artists craved. In the early nineteen nineties, we were already organising exhibitions in the Netherlands and Germany, collaborating with the Polish Institutes[82] in various places and treating it as a broadening of the gallery’s activities and those of the artists connected to us. We strove to show Polish art abroad and we managed that really quite well, I think, because those exhibitions number in the dozens; there were some thirty or forty of them outside Poland and that includes some outside Europe.

However, points east definitely took shape for us during Journey to the East. That was a decisive moment… which is not to say that we hadn’t previously shown Ukrainian or Belarusian exhibitions; we had, but we hadn’t thought about it systemically. Journey to the East was an exhibition that was proposed to me by Kasia Wielga, who worked at the National Centre for Culture at the time. It was going to be a spectacular project with a massive budget, carried out as part of Poland’s presidency of the Council of the European Union. I started wondering how to emerge with face from a proposal that was, when all’s said and done, somewhat political, and I recognised that it would be only right to go beyond the EU. The basis was the Polish-Swedish Proposal in respect of the Eastern Partnership initiative and, pursuing that trail, I decided to invite artists from countries aspiring to become members of the EU. For me, it was the chance for a fantastic adventure… I did research in Armenia and Georgia, examining an area that hasn’t been particularly well studied; first and foremost, though, it was a wonderful collaboration with Anna Łazar[83].

When we received the contract from the National Centre for Culture, our accountant almost died. She said they’ll never let us out of prison, that the project was totally out of our league, we’d never, ever be able to see it through, we didn’t have the tools to carry to out… The budget for that project was exactly the same as our entire annual budget for the Arsenal… a million. It’s kind of my character flaw that, despite sensible advice, I don’t know how to withdraw. While we were working on it, I met masses of fantastic artists, curators and art theorists from points east, where, institutionally, everything’s ailing and failing , but the people are fabulous and have an outstanding awareness; they’re wonderful to work with. It was a combination of two processes, an exhibition and event in one; on the other hand, though, you simply meet those people and become friends with them. Somewhere within the conversations, within the essays for the catalogue, a thread cropped up concerning playing with the exotic and the sense of being used that often accompanies curators from that region. That made me realise how crucial continuity is in terms of working together to build a partnership. Since then, there’s always been a place for art from the east in our plans; apart from numerous smaller projects, we’ve also carried out several large-scale ones like Deprivation, which was an exhibition about migration, and Attention! Border, which was crated in collaboration with Waldek Tatarczuk and Labirynt[84].

Of course, I’m never going to have the kind of budget that I did for Journey to the East, but you still have to think about continuing in an area. And I’ve been consistent about not abandoning it ever since. That was in 2011 and since then we’ve managed to hold a larger exhibition more or less every three years, presenting twenty to thirty artists. Deprivation, in 2014, was part of that sequence and it was in that context that we created Attention! Border with Waldek Tatarczuk and Labirynt.

What does collaborating with those artists involve these days?

It’s a really dynamic community, particularly Ukraine; unaffected, fresh and genuinely engaged. Working with them is a pleasure. The level of discourse that takes place there impresses me. I try to collaborate with them in a range of fields… not only exhibitions, but also residencies, educational projects, which I’ve carried out in Ukraine and Moldavia, and purchasing works. A few years ago, I was on the jury for the Malevich Award organised by the Polish Institute in Kiev. This year, the Polish Institute in Tbilisi established the Zygmunt Waliszewski[85] Award on the same principle, in order to bolster and strengthen the community of young artists in Georgia. I try to stay closely на связи.

With Anka Łazar, after the opening of ‘Places’ exhibition at the National Museum of Art in Kyiv, courtesy of Monika Szewczyk

Your strategic partner is Waldek and the BWA in Lublin. You’re a bit like astral twins.

Eastern understanding. Waldemar and I are oriented eastwards, we often work with the same artists and instead of depriving each other of energy, we share it. Generally speaking, it’s very nice that we operate on the basis of collaboration and not competition.

Tell me something about what you’ve so splendidly termed ‘the firm’. What’s the Arsenal team that you’ve formed like? What is ‘the firm’ to you?

As far as teamwork’s concerned, I’ve truly been very lucky in life. I worked at the museum first, so I know what workplace relations can be like, what they’re often like and how oppressive they can be. Things change, obviously; people come and go, there are various dynamic situations and good and bad moments, but all in all, it’s very good. People working in a cultural institution like ours are perpetually underfunded. The truth is that they have to be crazily available and they work incredibly hard. We often talk about whether it might be a good thing to slow down a bit, not hold every event that pops into our heads, cut down… sacrifice quantity in favour of longer exhibitions. We can’t compete with ourselves because the potential participating public has its limits, too. And then I hear “But it’s hard to refuse when someone asks for workshops”…

When we were working on Journey to the East, we processed that massive task like a factory… we worked terribly intensively, but everyone also had lashings of fun and tremendous satisfaction. They were tired out, of course, but they look back on those events to this day. Afterwards, we gave ourselves a holiday in the form of a trip to Kruszyniany[86], complete with campfires, horse riding, archery and hunting for wild mushrooms. They’re wonderful people, committed to their work and, just as important, we simply like each.

Where do you find them? There’s no arts HEI in Białystok…

It’s problematic. We’ve just advertised for curator… We’re searching throughout Poland, because there are no arts courses, there’s no art academy or art criticism. But there are creative, inventive people who want to learn something and set about learning it. We have plenty of major achievements in terms of encouraging people to get involved in art… there are several superb curators working in Poland and abroad who cut their teeth at the Arsenal.

How did you shape the team? What structure did you give it? As I understand it, it’s fairly horizontal; you’re author, director and curator. How do you settle on your curators?

For quite some time, I basically created seventy per cent of the exhibitions myself, but for several years now, I’ve really been trying to make it more horizontal. Now it’s not me confirming the exhibition programme, but us discussing it as a team. I have the last word, that’s obvious; I’m the director, but it’s very important to me that the staff have a sense of agency and authorship. I try not to dominate. The staff have to have some pleasure and I give them a sense of authorship. For instance, Małgosia Kowalczuk, who is usually my PA, and Magda Wieremiejuk, who’s normally involved with PR, dreamed up a festival of artistic books for children and they’re working to bring it to fruition because they’re interested in it and it’s what they need.

Translated from the Polish by Caryl Swift

[1] The largest city in north-east Poland, Białystok is the capital of the Polesia region – trans.

[2] Sławomir and Cecylia Chudzik – ed.

[3] Związek Polskich Artystów Plastyków: the Polish Visual Artists’ Union – trans.

[4] A town in north-east Poland, situated around eighty-four kilometres/fifty-two miles south-west of Białystok – trans.

[5] Włodzimierz Łajming (born 7.02.1933), painter, drawer and professor of fine arts – trans.

[6] Biuro Wystaw Artystcznych (BWA; Artistic Exhibitions Bureau). Established in the post-war era, the Warsaw-based Central Artistic Exhibitions Bureau (CBWA) not only held exhibitions, but also coordinated the work of a steadily growing national network of regional BWA branches. After the fall of communism, the CBWA was closed. However, a number of towns and cities across Poland have a functioning BWA to this day.

The Białystok BWA, which was set up in 1965, became the Arsenal Gallery at the beginning of the nineteen nineties – trans.

[7] Collector – trans.

[8] The exhibition ran from 05.08. to 30.09.2011 – ed.

[9] The Slendzińskich Gallery – trans.

[10] Białowieża, a village located in north-east Poland, some ninety or so kilometres/fifty-six miles south-east of Białystok. The village lies on the border with Belarus, at the heart of the primaeval Białowieża Forest – trans.

[11] Hajnówka, a town in north-east Poland, situated close to the border with Belarus, around seventy kilometres/forty-three miles south-east of Białystok – trans.

[12] Jerzy Panek (11.12.1918 – 5.01.2001), graphic artist and painter – trans.

[13] Jerzy Nowosielski (7.01.1923 – 21.02.2011), painter, graphic artist, set designer and illustrator – trans.

[14] Now the Muzeum Podlaskie w Białymstoku (Podlasie Museum in Białystok) – trans.

[15] Jerzy Ludwiński (2.01.1930 – 16.12.2000), conceptual art theorist, art critic, journalist and professor of art history – trans.

[16] Jan Świdziński (25.05.23 – 9.02.2014), intermedia, conceptual and performance artist, art critic and philosopher – trans.

[17] Janusz Stock (born in 1953), photographer and video artist – trans.

[18] KUL; the Catholic University of Lublin, now the John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin – trans.

[19] The Independent and Self-Governing Trade Union ‘Solidarity’ was founded at the then Lenin Shipyard in Gdańsk in 1980 as a result of worker protests. For the next nine years, it continued to use civil resistance to press for workers’ rights and social change, eventually entering into the negotiations with the communist government which led to the first multi-party elections in Poland in more than forty years – trans.

[20] Martial law was introduced by the government of the communist People’s Republic of Poland on 13th December 1981. It was lifted on 22nd July 1983 – trans.

[21] Stanisław II August, also known as Stanisław August Poniatowski (17.01.1732 – 12.02.1798), was the last king of Poland. He abdicated shortly after the Third Partition of Poland, which eliminated the sovereign Polish state for one hundred and twenty-three years, was signed in October 1795. In the communist Poland of the nineteen eighties, the most conservative HEIs deemed the history of art to end either in the late eighteenth century or in 1939 – trans.

[22] Andrzej Ryszkiewicz (5.05.1922 – 13.09.2005), art historian, researcher into, and expert on, Polish painting, the history of collecting, Polish-French artistic relations and eighteenth and nineteenth-century artistic culture – trans.

[23] A group of painters who had studied under Professor Tadeusz Pruszkowski at what was then the Warsaw School of Fine Arts. The group was active from 1929 to 1939 – trans.

[24] Kazimierz Dolny, a town in central east Poland, around fifty-five kilometres/thirty-four miles north-west of Lublin. It has long been a favourite with artists – trans.

[25] Andrzej Mroczek (1941 – 24. 06.2009), art historian, curator and director of BWA/Galeria Labirnyt in Lublin – trans.

[26] Andrzej Partum (16.09.1938 – 1.03.2002), intermedia and performance artist, painter, poet and author of manifests and of theoretical and critical writings on contemporary art – trans.

[27] Gerhard Blum Kwiatkowski (22,10.1930 – 11.08.2015), painter, installation artist, art theorist and formulator of the concept of reductive art– trans.

[28] Zbigniew Warpechowski (born in 1938), visual and performance artist and poet – trans.

[29] Jerzy Truszkowski (born in 1961), painter, performance, installation, film and video artist, photographer and author of writings on the history of art, art theory and art criticism, is also known by a pseudonym, Max Hexer – trans.

[30] Jan Tarasin (11.09.1926 – 8.08.2009), painter, graphic artist, drawer, photographer, essayist, and visual arts professor – trans.

[31] Stanisław Kuskowski (29?.04.1941 – 24.02.1995), painter – trans.

[32] A route running from the south-west, close to the border with what was then Czechoslovakia, via central-south, central-east, north-east Poland and the Baltic coast in the north central region, before returning to the south-west – trans.

[33] Jacek Woźniakowski (23.04.1920 – 29.11.2012), art historian, writer, essayist, columnist, journalist, editor literary translator and professor – trans.

[34] Wiesław Juszczak (born 26.06.1932), art historian, theorist and philosopher, essayist and professor – trans.

[35] Elżbieta Grabska-Wallis (19.01.1931 – 11.06.2004), art historian and doctor of history – trans.

[36] Małgorzata Kitowska-Łysiak (28.12.1953 – 17.10.2012), art historian, theorist and critic – trans.

[37] Located in south-west Poland, near the border with what was then Czechoslovakia – trans.

[38] Andrzej Bonarski (born in 1935), writer, journalist, businessman, visual arts patron and collector – trans.

[39] A former metalworks in Warsaw – trans.

[40] At the time, the Arsenal Gallery was still the Białystok BWA – trans.

[41] The communist Polish Workers Party – trans.

[42] Izabela Marcjan (1934 – 2.01.2013) – trans.

[43] Michał Jachuła, art historian, author of writings and interviews, currently a curator at the Zachęta National Gallery of Art in Warsaw – trans.

[44] Jacek Sempoliński (27.03.1927 – 30.03.2012), painter, drawer, teacher, critic and essayist – trans.

[45] A group formed in late 1985 by three recent graduates of the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts, Mirosław Bałka, Marek Kijewski and Mirosław Filonik. The group, or ‘consciousness’, as they termed it, which was originally called Neue Bieriemiennost, made its debut in early 1986 and the artists continued to work together until 1989 – trans.

[46] Gruppa, an artistic group founded by a group of Warsaw Academy of Arts graduates interested in Neo-Expressionism. Gruppa ceased to operate in 1992 – trans.

[47] Małgorzata Niedzielko, sculpteress – trans.

[48] Leon Tarasewicz (born in 1957), painter, installation artist and visual arts professor – trans.

[49] Józef Szajna (13.03.1922 – 24.06.2008), painter, set designer, theatre director and professor at the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts – trans.

[50] Mirosław Bałka (born 16.12.1958), sculptor, drawer, experimental film- and sound maker, professor at the Warsaw Academy of Fine Art – trans.

[51] Saint Wojciech, also known as Saint Adalbert of Prague – trans.

[52] Marek Kijewski (1955 – 19.08.2007), sculptor – trans.

[53] Mirosław Filonik (born 11.05.1958), sculptor, object maker and installation artist – trans.

[54] Mirosław Smoczyński (22.03.1955 – 2.01.2009), painter, drawer, performance and installation artist – trans.

[55] In the sense that the Poles would be living in an independent Poland, free from Soviet rule – trans.

[56] Ryszard Woźniak (born on 13.06.1955), painter, performance and installations artist, art theorist and teacher – trans.

[57] The Foksal Gallery in Warsaw – trans.

[58] Ewa Zarzycka, drawer. performance and installations artist – trans.

[59] Józef Robakowski (born 20.02 1939), multimedia and installations artist, photographer, filmmaker and professor at the Łódź Film School – trans.

[60] A gallery in Łódź, in central Poland, the Wschodnia (Eastern) began operating in 1981 – trans.

[61] Run by the Warsaw branch of the Związek Polskich Artystów Plastyków (Polish Visual Artists’ Union) – trans.

[62] Zbigniew Warpechowski (born in 1938), poet, visual and performance artist – trans.

[63] Oskar Dawicki (born on 28.07.1971), multimedia, performance, video, and installations artist, photographer, documentarian and object maker – trans.

[64] A city in west-central Poland – trans.