While I was working on this essay for the East Art Mags (EAM) network as part of an International Visegrad Fund grant project, I drew inspiration from Timothy Garton Ash. In an opinion piece entitled Europe Must Stop This Disgrace: Viktor Orbán Is Dismantling Democracy, published in a British daily newspaper, “The Guardian”, on 29th June 2019, Professor Ash turns a critical eye on what he terms the “hybrid regime” currently ruling Hungary.

To the astonishment of the protesting artistic community, Orbán’s government has dropped yet another series of reforms to the cultural sphere. The elimination of the Nemzeti Kulturális Alap / National Cultural Fund of Hungary has thus been brought to a halt and, at the same time, the brakes have been applied to the process of annihilating autonomy in the arts.

I was planning a week-long residency in Budapest, where I would meet up with Hungarian artists in order to gain a better understanding of the situation in the visual arts and Hungarian culture at present. Are things really as bad as they seem? How do socially and politically sensitive artists cope in an atmosphere which has been compared with authoritarian regimes? Do politics actually matter to them at all?

The EAM network is managed by two Hungarian visual arts professionals who are also friends. One is Gergely Nagy, the editor-in-chief of Artportal.hu, and the other is Barnabás Bencsik, the founder and owner of the Glassyard Gallery. Together, the three of us drew up the list of artists I would meet during my stay. It was important to me that they constituted as representative a group as possible, encompassing painters, performance artists and photographers, women and men, younger and older. While it is relatively easy to reach out to interesting contemporary artists who contest Orbán’s regime, divisions within the visual arts community mean that none who identify with their prime minister’s policies made their way onto the list. I chose to focus on Budapest, which dominates the Hungarian arts and throws a daunting shadow over smaller arts scenes like those in Pécs or Kecskmét, for instance.

***

The beginning of December 2019. I arrive in the city. To the astonishment of the protesting artistic community, Orbán’s government has dropped yet another series of reforms to the cultural sphere. The elimination of the Nemzeti Kulturális Alap / National Cultural Fund of Hungary has thus been brought to a halt and, at the same time, the brakes have been applied to the process of annihilating autonomy in the arts. Like the recent election of a little-known opposition politician, Gergely Karácsony, as mayor of Budapest, these successes have been received with incredulity and are hot topics of conversation. The change to the situation lends a lightness of heart to my meetings and the cheering effect blends with the mood of the final pre-Christmas exhibitions and gallery sales.

I will be meeting up not only with artists, but also with curators and administrators connected with visual arts institutions, as well as attending events like the Esterházy Art Award ceremony at the Ludwig Museum. Curator and critic Andi Soós attends some of the meetings with me and her help is invaluable, both in translating to and from Hungarian and in shining a light on countless details of the city’s artistic life. As it transpires, the artists’ perceptions strike me as being the most interesting, so they become the crux of my essay.

The Joy of Process

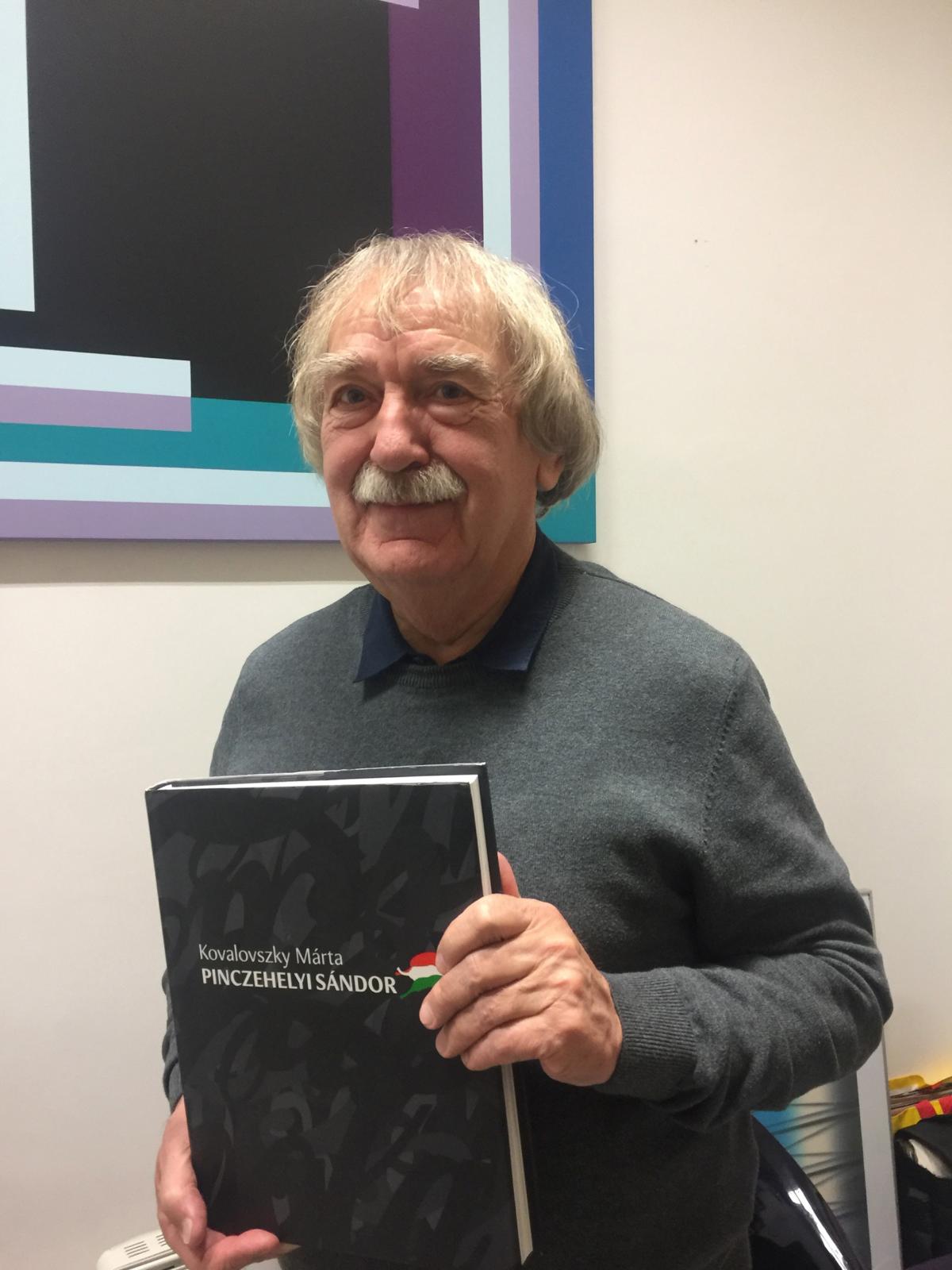

I meet up with Sándor Pinczehelyi at the acb Gallery, which is located in a gorgeous, albeit profoundly dilapidated, historical apartment building with a stunning patio worthy of a mansion. This is the most powerful private gallery in Hungary and our encounter takes place amidst the intense buzz of the festive season. The corridor is stacked with works packed up and waiting to be transported to customers. Paradoxically, those works may well prove to be the ones that survive.

Sándor Pinczehelyi has travelled into the capital from Pécs, where he lives and works. He will be exhibiting his newest works at the acb in the spring of 2020. He seems overawed and muted. This is surprising, given that he is a legend on the arts scene and one of the most distinctive artists of the post-war avant-garde. Once a courageous critic of the communist regime, he shuns politics these days. “Let the young people save the world. I’ve done my bit,” he says.

Pinczehelyi’s focus of artistic interest is mass production and the use of a variety of techniques. In essence, this gives rise to works which are akin to the pop art tradition. He returns to motifs and images from his childhood, reworking them and updating them. It is an art which is existential in its own way, with some of his works alluding to his early years. In comparison with the earlier hammer-and-sickle motifs and national colours of Hungary which often appeared in his iconic works, his new art is colourful, with a delight of its own. It is even decorative. Pinczehelyi is interested in the creative process and the joy of creating that goes hand in hand with it. It is an approach which might seem naïve or conservative, but, in the hands of a mature artist who has come through decades of communism and transformation, it is authentic and has to be respected.

“Is art important?” he asks rhetorically. “Is an artist’s work capable of changing anything?” He notes that the combination of art and politics is a Hungarian curse since, to an extent, political engagement can result in provincialism. His tools for opposing the Hungarian obsession with Hungarianness are lightness, irony and distance. On the other hand, he sets store by his older, political works, where national motifs and politics played an important role.

Gábor Erdélyi and Tóth Árpád

Soft Humour

For my meeting with Gábor Erdélyi, I make my way to the Neon Gallery which, as it happens, is hosting an exhibition of his latest paintings. Erdélyi works slowly. A painting a month; sometimes once every two months. I do the maths in my head. Say ten paintings a year; multiplied by fifty years spent working, that gives us a total of five hundred works. Erdélyi compares his paintings to children and their creation to giving birth. Not that he has a problem with parting from individual works, though. Completed, exhibited and sold, they go out into the world. His abstract, small-scale compositions are provided with Hungarian titles that appear to be amusing. In translation, at any rate. Like Soft Humour, for instance.

The Neon Gallery is an adapted flat in a historical apartment building. The paintings in the large exhibition room are hung symmetrically, in an arrangement reminiscent of a chapel. As we move from work to work, we talk about spirituality and even about religion. Erdélyi seems surprised and disconcerted by my question as to whether he believes in God. He is more engaged with himself, his thoughts and emotions and with his work with the history of painting. The work on display here is not so much the vestiges of painting as an exploration of the space in-between. He is, indeed, interested in the edges and corners, the support and the layers creating the painting, but his interest goes further. This is postmodernist art. Only, does postmodernism have any sense or meaning in the twenty-first century? Is it possible to evince an outlook on life through art of that kind? Without a doubt, yes.

Sándor Pinczehelyi seems overawed and muted. Once a courageous critic of the communist regime, he shuns politics these days. “Let the young people save the world. I’ve done my bit,” he says.

Erdélyi has no interest in politics. He is, however, interested in football. He enjoys playing it, but I completely forget to ask him which position he takes. He does not view his exhibition of abstract painting as a kind of political statement. Is it possible to create painting of that nature today? In times crazed and decadent from politics, it is difficult to maintain that kind of mindfulness and conviction towards what one is doing. Yet Erdélyi seems to be managing to do just that.

While I am talking to Erdélyi, I have the help of Tóth Árpád, the owner of both the Neon and an auction house. When asked about the market, he smiles and replies that business is booming and people are eager to buy art. It looks as if the taxi driver who took me to the meeting hit the nail on the head when he said that Viktor Orbán was in the right place at the right time; a period of prosperity. People are well-off and happy to forgive the populists their sins. Just as long as the money’s there.

Cul-de-Sac

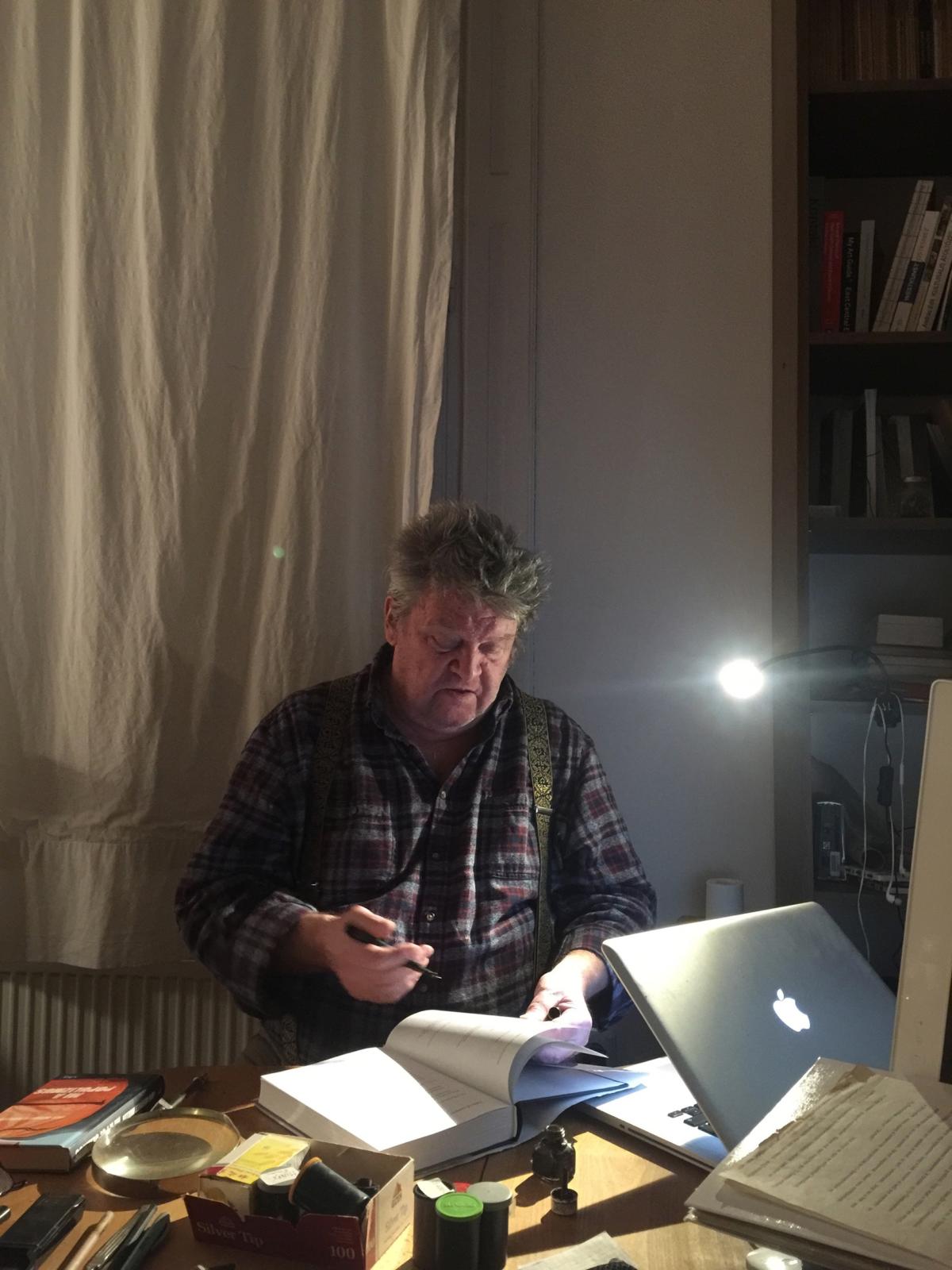

My meeting with the Little Warsaw duo takes me across the Danube to Buda and a studio in a historical townhouse. Our conversation lasts more than an hour and the dominant voice belongs to Bálint Havas. Although András Gálik, the other half of the duo, sits right alongside and listens intently, he only joins in at the end.

The discussion begins with a historical outline which underscores the collapse of the visual arts scene that took place after Victor Orbán came to power a decade ago. As the staff in the visual arts institutions changed and the new authorities’ appointees took over, the Little Warsaw duo, whose career had peaked in the noughties, began to sense what would become a growing void. The curators they were close to gradually went abroad. Purchases of Little Warsaw works for public collections dwindled away and invitations to exhibit became rarer and rarer, as did opportunities of showing their works at international events. To cap it all came generational change. Young artists and curators inevitably have little interest in former stars whose glitter has slightly dimmed. Bálint Havas reaches for a French expression to describe the situation they found themselves in. “A cul-de-sac,” he says. “In that case,” I ask, “when you’re faced with a wall, what’s to be done?” “Nothing,” Havas replies. “Or almost nothing.” On the other hand, the duo recognises a dead-end like that as something positive and inspiring, making it possible to take a step back and spend some time thinking their own work over. They refute the suggestion that this is typical Hungarian melancholia, if not to say depression. Nonetheless, being weary of the current, hopeless situation, they now want to look back on the history of the post-communist transformation and search for the sources of stagnation.

When I ask them to select a recent work of theirs which they consider to be important, they choose a substantial book or, to be absolutely precise, photo-comic. Entitled rebels, it is devoted to the situation at the Hungarian Academy of Fine Arts during the fall of communism. Screenshots of VHS recordings are provided, complete with speech bubbles, and complemented by essays and commentaries. This is research into an unsuccessful rebellion and the systemic change of 1989. The duo’s declared desire for topicality and wish to reach beyond the local scene seem to stand in opposition to this hermetic work. Hungarian art is apparently a problem, but more universal questions are of no interest to them.

Dominika Trapp’s courageous tackling of the Kulturkamf being waged in Hungary is actually the reason why she began to engage with folk art, which is held up in opposition to contemporary work by ideologists in circles close to Orbán.

Asked for a definition of art, Little Warsaw replies that art can be anything. It is the art of relating, the art of research. “In that case,” I ask, “what is art not?” To Havas, “it isn’t family and children, for example”. Separating the personal from the political and artistic evidently presents no problem for them when declaring their engagement. They have no interest in feminism and LGBTQ topics, although they do appreciate the work of Dominika Trapp, for instance. Another question, this time about young art, receives a truculent response; they themselves are young and they feel even younger than the most youthful generation of artists. At the end, the conversation shifts to Hungarian surnames. The two most common are ‘Nagy’ and ‘Kis’ or ‘Kiss’. The former translates as ‘big’ and the latter, as ‘small’.

Folk, Art & Prolapse

Everyone is talking about Dominika Trapp. Asked about the most interesting and on-trend young art, about ‘what’s hot and what’s not’, people invariably mention her. It turns out that the Kelet Café, on the Buda side of the river, is a favourite of hers, so I meet up with her there. She has just returned from New York and is preparing for an exhibition at the Trafo Gallery, one of the most interesting spots on Budapest’s visual arts map.

Trapp has previously been represented to me as a feminist, but I find myself face to face with an artist whose starting point for her own story about herself and her work is folk art and her doctoral research at the Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design in Budapest. She is endeavouring to cross not only the divisions that exist on the visual arts scene, but also the front line in the Hungarian-Hungarian ideological war. Her courageous tackling of the Kulturkamf being waged in Hungary is actually the reason why she began to engage with folk art, which is held up in opposition to contemporary work by ideologists in circles close to Orbán. The theory is that traditional folk art will counter the art ‘dragged in’ from the West by the liberal elites. It is to be the foundation and mainstay of Hungarianness.

So Trapp decided to combine climate activism and political engagement by appropriating the discourse of the pro-government ideologists. To present her counter-narrative, she set up a project entitled Peasants in Atmosphere and, as part of the project, founded what she has called a ‘conceptual-folk-music band’ of the same name. Through the lyrics of its songs, the band speaks out on topics utterly unlike traditional themes. In the face of planetary catastrophe, Orbán’s regime seems a trivial matter and Trapp is focused not so much on activism as on a kind of grief, of mourning, as if the end of the world has already come. As an academic at the Moholy-Nagy University, she cites the writings of theorists who claim that it is already too late to save the planet. Perhaps the ways of acting and thinking which lie dormant in traditional culture, along with long-forgotten technologies and tools, will make survival possible? She is an advocate of Jem Bendell’s ‘deep adaptation’. “Most probably only tribes, groups of people will survive, I’d say,” she remarks. “Maybe not only Hungarians,” I think.

Dominika Trapp, photo: Eva Szombat

The second part of our conversations covers Trapp’s new works. During her residency in New York, she was involved in choreography and reworking the patriarchal models of folk culture. For the Trafo exhibition, she is also preparing some works related to pornography. Her focus is on the normalisation of BDSM and how women function in the porn industry. One of the lesser-known aspects of Hungarian culture and the Budapest scene is, in fact, a submersion in pornography. Like Prague, the city is a global centre of the porn industry.

Trapp tells me that she is particularly interested in “prolapse”. I am forced to confess; “I’m not sure what you mean. You’ll have to explain it to me”. Rectal prolapse, where the rectum, located at the end of the large intestine, becomes displaced and slips downwards to protrude through the anus, creates a fairly specific iconography which converges with her folk-orientated work in an unexpected way.

It might be that, hidden within Trapp’s art is a solution to the problem of localness, of Hungarianness, which, in turn, conceals within itself an answer both to the universal problems that humanity is facing and to the existential questions torturing various people in some way. Not only Hungarians. It calls to mind Béla Bartók’s work on the borders of ethnography. Trapp provides me with a graphic description of the effects of a prolapse. As we part, I am swept by feelings of dread as I contemplate doing an Internet search in order to see what one looks like.

Timeless

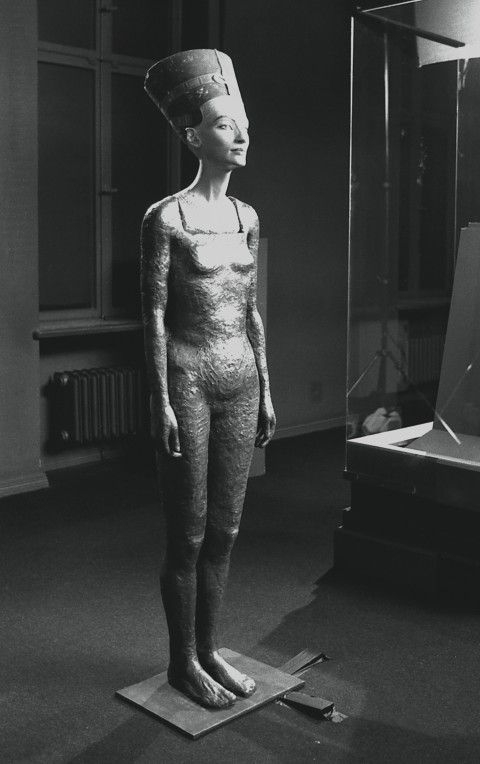

Imre Bak means the same to the Hungarian visual arts scene as Frank Stella does to its American counterpart, with one difference; the eighty-year-old Bak is still alive and in excellent form. To meet him, I return to the acb Gallery, which is currently holding an exhibition of his most recent paintings, bright, cheerful works that emanate life energy, engage the emotions and please the eye.

Bak begins with a story about the origins of his art. At my request, we shift to the present day. I am not concerned with recollections and the thinking of years ago, which is very well-known. What interests me is what he is thinking and creating today. He tells me that he follows the latest trends in painting and visual art on the Internet. As far as he can, he tries to see exhibitions both in Budapest and abroad. He endeavours to convey the spirit of the times and aims to establish a dialogue with the present day and, at the same time, to take his paintings beyond time. The situation in Hungary is of no particular interest to him.

The director of the acb Gallery, Orsolya Hegedüs, confesses that they have been very busy in recent years. This is not only because interest in contemporary art is growing and the prices of works are rising, but also because, like it or not, private galleries have stepped into the role of public institutions.

Bak recalls Béla Bartók, whose genius he sees in the fusion of the Hungarian element and the universal. In this, he reminds me of Dominika Trapp. What interests him in art is spirituality and conveying energy through his paintings. Metaphysics yields to an interest in abstraction, in geometry, in an idiosyncratic order of things and the harmony he seeks. My question about current politics is dismissed. He would rather talk about art. He cites Matisse. During the communist era, abstraction had political undertones because it was connected with the influences of Western art. “Might it also have some kind of political significance today?” I ask. “Certainly,” he replies. “As a space of artistic freedom, as a response to crisis and political dominance. In that context, art is a move beyond the here and now, beyond all the short-lived, hasty and temporal confines and problems.”

We visit the exhibition together. Bak speaks of his works as self-portraits and interior landscapes. He works not on an easel, but with the canvas lying flat on a table. The size of a picture is determined by the reach of his arm. His scale is human. Most of the paintings consist of several smaller ones. The other two exhibitions spaces hold some of his older works, particularly from the nineteen eighties. They are akin to figuration and come close to narrative. “That’s how things were back then and that’s how you painted,” he remarks. The works are for sale, of course. Years ago, the cost of the earlier works would have been unremarkable. Nowadays, every single one of them is worth a fortune. They come from his private collection. “The notion of saving some of my work for my old age… now, that was an excellent moment of intuition. I should have kept hold of even more of them,” he says with a smile.

Under Pressure

The director of the acb Gallery, Orsolya Hegedüs, is with us during my meeting with Bak. She confesses that they have been very busy in recent years. This is not only because interest in contemporary art is growing and the prices of works are rising, but also because, like it or not, private galleries have stepped into the role of public institutions. Bureaucratisation and politicisation mean that curators, critics and scholars home in on places like the acb, which have become the focal points for artistic life.

Hegedüs’ words are borne out by the bustle in the gallery. People are constantly to and froing, coming and going, chatting, greeting one another, arranging to get together… So, when the time comes for my meeting with Ágnes Eperjesi, she and I set off in search of a quiet nook where we can talk. We wind up in the acb’s spacious storeroom, giving me a chance to explore yet another space in this extraordinary ‘mansion of art’.

Eperjesi is an artist who focused on photography at the beginning of her career, specialising in photograms and abstraction. She has gradually became more and more involved in politics, taking part in protests against Orbán’s doings. Her art, too, has changed beyond all recognition, with photography giving way to performance art, installations and public appearances. She is critical of the mechanisms of power and the male domination which is discernable not only in conservative visual arts HEIs, but also throughout the contemporary visual arts world in Hungary. She reworks the present-day situation by turning to fairly recent history, particularly the nineteen eighties and that decisive turning point which was 1989. Like Little Warsaw, she is asking what went wrong. Why did the model adopted for transformation prove to be so conservative and, fundamentally, so misogynistic? She is clear-sighted as far as the weakness of the feminist movement in Hungary is concerned. As an academic teacher, she is aware that universities and other HEIs are one of the last bastions of freedom. “Mind you,” she remarks, “dominated as they are by men, they could do with something along the lines of #MeToo.”

Miklós Erhardt

While we are talking about the situation in Hungary, Eperjesi says: “I wouldn’t decide to emigrate, because of my bonds with the local scene and the artists I’m close to”. It is as if her personal career is less vital than responsibility and attesting to her attitude as regards other potential scenarios. Yet she seems to be under pressure, weary of activism and of fighting populist politics. “Like most artists, I take part in the protests and demonstrations,” she says, “but in my art, I’m at the stage where I’d like to be focusing on something else.” Hence her return to her earlier works, beautiful, abstract photograms which she has now compiled in book form. They are wonderful works which go beyond the divides of sex and politics to unite with the great tradition that goes back to the times of Laszlo Moholy-Nagy.

The Biggest Problem in Life

Miklós Erhardt is the only artist I meet up with who chose to emigrate. He works in Budapest, at the Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design, but lives with his family two hours away, in Vienna. “Vienna’s bourgeois and riddled with bigotry,” he tells me, “but it’s a convenient city, full of visual arts institutions and galleries of international stature.”

We are sitting in the Lumen Café and talking about politics and the entanglement of artists in the current situation. Erhardt is aware that, for many artists, Orbán’s government is not really all that bad. He is not only referring to conformists employed within the authorities’ apparatus and subordinated institutions. A great many artists live in a world of their own, seeking freedom in their studios and the HEIs. “Young artists, in particular,” he states, “completely ignore politics.” He considers that he himself was a more political artist in pre-Orbán times, and therefore before political engagement, at any rate declared, became ‘a thing’. He was interested in criticism of Neoliberalism and the cant of social democratic governments. It was the fiasco of the transformation and the failures of the parties concerned that elevated Orbán. Erhardt focused on social inequalities. He was involved in working with socially excluded groups and the homeless, acting both collectively and alone.

Like Little Warsaw, Ágnes Eperjesi is asking what went wrong. Why did the model adopted for transformation prove to be so conservative and, fundamentally, so misogynistic? She is aware that universities are one of the last bastions of freedom. “Mind you,” she remarks, “dominated as they are by men, they could do with something along the lines of #MeToo.”

Recent years have brought a change. First, as an HEI teacher, he tries to have an effect on upcoming generations of artists by making them aware of the mechanisms used for indoctrination purposes by the holders of power. Second, he is more reflective, or even existential, in his approach to visual art. I ask him what he considers to be representative of the current stage in his work. “The video that recreates the ten-minute monologue spoken by the Romani man who is the central character in István Dárday’s Princess in Rags and Tatters.” Dárday’s black-and-white documentary was made in 1974. Erhardt’s black-and-white video is a re-enactment where he identifies with the anonymous protagonist, stepping into his shoes, his situation and social condition. The Romani man and Erhardt talk about their lives, about their problems, about their daily routines and about the reasons why, rather than achieving success, they have suffered failure. Not some kind of spectacular defeat, but common-or-garden, human failure in life. After all, vegetating can also be failure, as can a lack of remarkable achievements, everyday monotony and the need to adapt to the surrounding world. On the other hand, if this is the greatest problem in the life of that Hungarian Romani and this Hungarian artist, then things are not actually all that bad.

Careerist

The day after the Esterházy Art Award ceremony, I head back to the Ludwig Museum to meet up with Peter Puklus. He is one of the three 2019 winners, but he missed the gala because he was running a class in Germany. A coincidence of sorts, but gestures of that kind assume symbolic proportions on the fairly narrow Hungarian visual arts scene. It is hardly surprising that, here and there, I hear critical comments about Puklus, who is recognised on the international scene. He himself is amused by this and takes it with a pinch of salt.

A handsome forty-year-old, Puklus has gone through a personal crisis and is emerging from it a new man. He is showing his latest works at the Ludwig exhibition. Already known as a photographer, he has also created installation and objects, but is now exhibiting as a painter for the first time… and, straight away, he has picked up an Esterházy, with five thousand euro as the prize. I ask him why he decided to start painting. “I always wanted to be a painter,” he replies. A showcase alongside his paintings holds notebooks of sketches. One sketch is a self-portrait entitled Careerist. He heard the epithet directed at him by jealous artist and drank it in.

Peter Puklus

We cross the river to Buda and the paintings, more expressive and rawer, but still a riot of colour and energy, in his studio, which is located in a former factory there. It has all kinds of spaces and Puklus is adapting them and transforming them into work spaces and storerooms. The paintings are the size of his bed and they have English titles. Puklus is also irritated by the situation in Hungary. As he describes it, the provincialism of the visual arts scene is driven by ‘who you know’, reinforced, in turn, by political connections. This determines who does what with whom and who is excluded. For artists who find themselves on the outside, the solution is a career abroad. The sky is the limit for Puklus’ generation and he readily seizes the opportunity this presents him, moving between Budapest, Dusseldorf, Warsaw, Paris and New York.

As an artist, Puklus is not especially interested in politics. Most of his work is concerned with his personal situation. He is his own central motif, along with his family. This is intimate art, but it is also persuasive because it addresses questions familiar to every representative of his generation and social class. He avoids monotony by introducing erotica. He is transforming himself from a predictable artist working on project after project into someone entirely different, an artist heedless of timing, of fully finishing works and of publishing successive books. His new paintings are stirring up controversies, but that accords with his thinking. Puklus is after everything… except predictability.

Presenting Nothing and Making It Visible

I arrive at Két Szerecsen, the wonderful bistro where I have arranged to meet Zsuzsa Magyari. Magyari, whose surname translates as ‘Hungarian’, has only recently graduated. She and a group of friends constitute the collective behind Pince, an artist-run, off-space. I was much surprised to discover that, although she is the youngest of all the artists I meet, she does not speak English. Thankfully, Andi Soós is with me and, with her help, the conversation flows.

Magyari is not a feminist and had no sense of male domination while she was a student. Well, with the possible exception of the entrance exams; with far higher numbers of women applying, men are favoured. I remark that it would be a challenge to find a woman artist in Poland who would renounce feminism. “One of my friends is a feminist,” she replies.

Zsuzsa Magyari

To an extent, Magyari confirms Erhardt’s comment about a young generation which takes no interest in the political situation. Even the off-space run by her and her friends is non-political in nature. Pince was founded for the practical consideration which remains its raison d’être. The young artists had nowhere to exhibit. So they made their own gallery and now formulate the programme collectively, clubbing together to create the exhibitions. Hanging around and waiting their turn at the Ludwig Museum is pointless, but so is counting on a career with a commercial gallery.

I delicately enquire about financial matters and the anxiety commonly felt by young artists coming to the end of their studies. “I work in a shop that sells toiletries for dogs,” Magyari tells me. “Art is a kind of additional activity. That way, I avoid frustration and create what I want to create. Art is part of life, a kind of lifestyle.” I ask her about her work. She shows me some photos of an installation composed of plastic bags and another formed from plastic sheeting balled-up to look like a crumpled quilt on a bed. “Beautiful. And poetic.” I say, “But not exactly ecological.” “When I use plastic in art, I’m sustaining a zero-waste lifestyle,” she retorts. I ask her what interests her in art. “Presenting nothing and making it visible,” says Magyari.

The Visual Aspect

Sunday. The Old Town. Another splendid, historical townhouse, this time right by the Danube. I am here to meet Gabor Ősz, who lives in a flat in the building. Because I know his wife, curator, writer and producer Claudia Kussel, things are going to be a bit less formal. I am invited to Sunday lunch. It was not so long ago that that Ősz and Claudia decided to return to Hungary after he had spent a quarter of a century in Amsterdam, where he met Claudia and where they started a family and raised their children. They decided to make the move for professional and family reasons.

Could there be two more diametrically opposed political and cultural contexts than the Netherlands and Hungary? Ősz is clearly irritated by both the Hungarian visual arts scene and the prevailing climate of aversion towards things Western, liberal and progressive. Not that the opposition to Orbán’s government is spared his dispassionate and critical gaze. As he sees it, apart from the desire to remove the Fidesz party from power, the opposition has not a single constructive idea for Hungary. What preceded Orbán might be considered as even worse than the present situation, like the fascists of the Jobbik party, for instance.

Ősz’s political views are one thing and his art is something else. As he talks, I sense a bitter misery in his tone, a homesickness for the Netherlands and a genuinely cosmopolitan culture free of nationalistic restraints. On the other hand, there is no surrender. He is standing fast and investing every effort in making the most of his international contacts and his position as an artist recognised in the West as he works on exhibitions in Budapest. He takes part in discussions on the condition of photography and the photographic image and is preparing an exhibition about photography where he intends to show not so much as a single photo.

Magyari is not a feminist and had no sense of male domination while she was a student. Well, with the possible exception of the entrance exams; with far higher numbers of women applying, men are favoured. I remark that it would be a challenge to find a woman artist in Poland who would renounce feminism. “One of my friends is a feminist,” she replies.

Our conversation turns to Ősz’s philosophy of photography, his photo books and his projects. He has returned to his works from the nineteen nineties, when he was mainly interested in rigid photographic conceptualism devoid of aesthetic values. Later on, he strove to combine the pictorial quality of the image with a concept that was gradually revealed to the viewer. He mentions Liquid Horizon, a series of photographs taken in former Nazi bunkers on the Atlantic coast in France, as a project that he considers both emblematic and satisfying.

We talk about Paul Virilio. About taking photos and pleasure. Liquid Horizon is a successful fusion of a conceptual approach to landscapes and the pleasure flowing from the image. Taking photographs of architecture and landscapes as a quest for beauty. Showing everything at once is pointless. Gradually revealing and zooming in. Photographing the beautiful body of a person unknown to us, but whom we admire.

Non-Artist

Tamás St. Auby, aka Szentjóby invites me into his flat in Polish. He has been to Poland several dozen times. The first visit was in 1960, when he was still a teenager. He knew Tadeusz Kantor. An annual, open-air event, the International Meeting of Artists, Arts Scholars and Art Theorists, was held every summer from 1963 to 1981 in the village of Osiecki on the Baltic coast. Szentjóby was there in 1967, when Kantor’s legendary Panoramiczny happeningu morski (Panoramic Sea Happening) took place. He was also in Poland on the night of 13th January 1981, when martial law was declared. He knows most of Poland’s arts theorists and historians, as well as the majority of the country’s Neo-Avant-Garde artists, and not only those of his own generation, either.

Szentjóby presents himself as a non-artist. “I’m interested not in art, but in theology,” he says, pouring us both a glass of palińka, a traditional, Hungarian fruit spirit. We discuss original sin and the consequences of the expulsion from Paradise. Keeping up with his stream of thoughts and associations is a challenge. He is in an excellent mood and laughs out loud every few minutes. I take this as a good sign, having been forewarned that he can be quick-tempered and is a past master at firing off stinging remarks. Before long, we move on from the Bible to Jesus Christ and something very important to Szentjóby’s art, namely, universal basic income. The concept is central to his work. At present, he is focused on building a basic income basilica, a kind of temple, a place for meditation and for running a residency programme for non-artists.

The question of talent or, rather, of its lack, interests Szentjóby. “Contemporary artists don’t have to create good art at all,” he says provocatively. “On the contrary, art should be bad today, so that it can be recognised as good tomorrow.” He tells me about his exhibition of thousands of bad drawings and shows me documentation of the event. “Everything’s going to the dogs, it’s getting worse and worse.” Yet Szentjóby is not bothered by this. If anything, it seems to please him, since more and more bad and talentless people will be able to operate as good, or even outstanding, artists. This is a perverse take on the notion that anyone can be an artist and that everything is art. Several times, I ask the same question. “Are you sure you’re not cynical in your attitude and activities?” He denies it, presenting himself as “a religious artist”.

The discussion turns to solipsism, to good and evil and to Swedenborg and Purgatory. Szentjóby reminds me that even the pope has admitted that hell does not exist. “And so we’re all in Purgatory and being tested,” he says. “Only what, in actual fact, is Purgatory?” I enquire. “And what exactly does the test consist of?” One thing which is important to Szentjóby is myth. Mythology, thanks to which, it is possible to break away from Purgatory and pass, conditionally, into Heaven.

When I ask about present-day politics, Szentjóby talks about the corruption of Orbán’s regime, about rising prices and about the impunity of officials who make life difficult for him in terms of running his foundation and building his Universal Basic Income basilica. Politics takes us to the concept of striking. “To me,” he says, “a strike is a fundamental artistic activity. It’s hard work that has to be carried out here and now, in our times, which are geared towards exploitation and productivity.”

Szentjóby is an artist of the international Neo-Avant-Garde, so questions about Hungary and the Hungarians seem inappropriate. “And yet,” I remark, “you’re building your basilica here, in Hungary.” “Of course,” he says. “Not far from the crater of an extinct volcano.” “I didn’t know there were volcanoes in Hungary,” I interject. “I hope that one erupts again some day and buries the whole of Hungary under its lava,” Szentjóby says, topping up my glass of palińka.

Translated from the Polish by Caryl Swift

This essay was written and published as part of the East Arts Mag programme and with the support of the International Visegrad Fund.