In the summer of 2023, the exhibition How Are You?, which aimed to represent the Wartime Art Archive, took place in the Ukrainian House, a five-story venue in the heart of Kyiv.

Today, art provides another example of the persistence of the Ukrainian struggle and becomes a mirror that reflects the destruction and dehumanization that Russia has imposed on Ukraine. The artists’ visions, shaped by this war, have merged into a collective sharing of personal and common wartime experiences, which are contributing to the recording of Ukrainian history and preventing it from being falsified or forgotten.

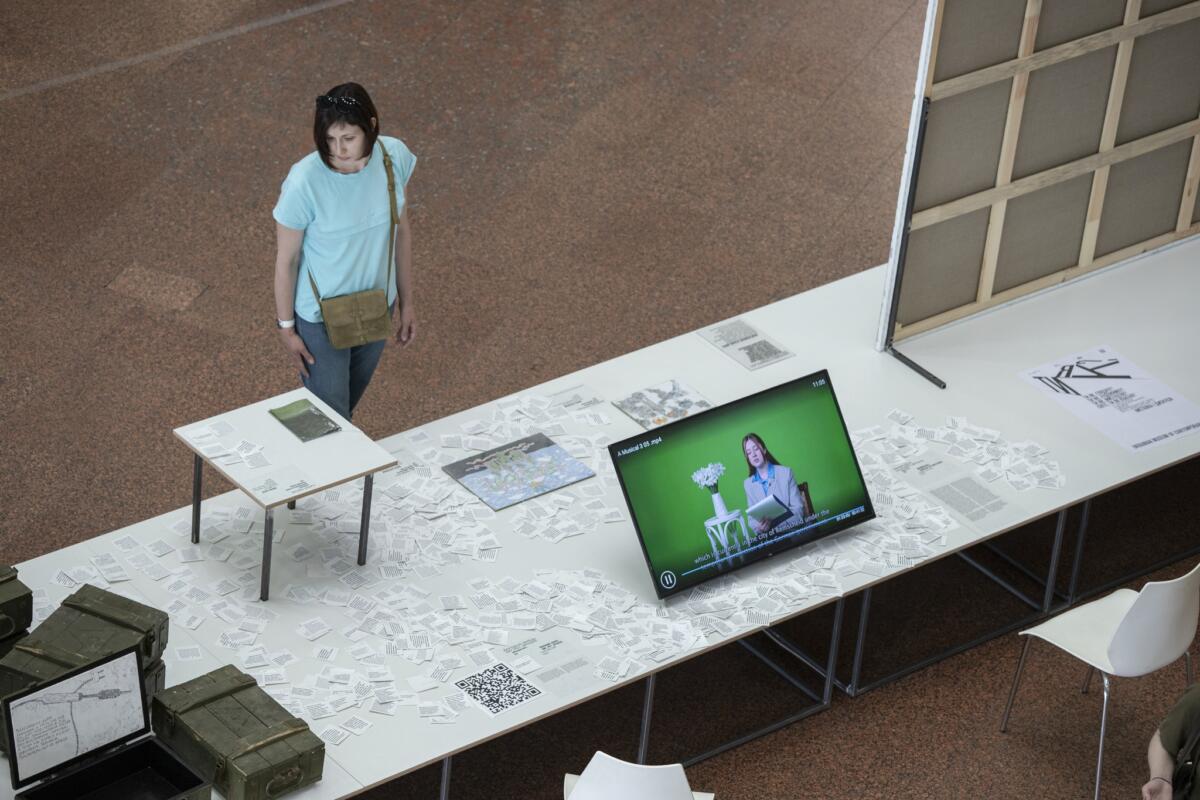

The extensive group exhibition How Are You? took place in Kyiv in summer of 2023, representing the Wartime Art Archive (WAA).[1] The collective of eight curators brought together more than 500 works of more than 100 Ukrainian artists of different generations and positions – from established to emerging, including non-traditional artists, such as patients of psycho-neurological clinics – to reflect the period of the full-scale Russian invasion in Ukraine from 2022-2023, in the context of the war that started in 2014.

The non-hierarchical approach in the selection of works is truly remarkable and resonates with the widespread involvement of Ukrainians in defending their country including through volunteering and raising funds for the army. One of my friends, Serhiy, who is an artist himself, voluntarily joined the Ukrainian Army Forces in March 2022. Serhiy is 54 now; he had undergone mandatory military training during the late Soviet era as a young man. Serhiy shared with me that, while there are certainly challenges within the military unit in present-day Ukraine, there is a significant difference from his earlier Soviet military experience. The absence of an internal hierarchy and the notorious “dedovshchina”, a practice of hazing junior soldiers, sets this experience apart. “We have a diversity in age, language, and ethnicity in our military unit”, Serhiy said, “but we, soldiers, treat each other as equal.”

The inclusivity of How Are You? aligns with this same trend. One of its organizers, the Ukrainian Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA NGO), an institution without a physical space thus far, believes that the “public dialogue in Ukraine is possible only if representatives of different regions and social groups participate in it. Therefore, we do not limit ourselves to the professional community, but seek to involve as many actors as possible — from the government to local communities, especially in the de-occupied territories.”[2] This has resulted in an exhibition that has made a rich diversity of voices accessible.

The concept of the Wartime Art Archive (WAA) is to contribute to the future ways of commemoration and to preserve the memory of ongoing traumatic events through art. The term “archive” traditionally pertains to the past, yet looking to the future from today, we wonder, what kind of past will our present be? What might be lost? And what should we do to prevent it from being lost? And, what does an archive emerging from ongoing, everyday shifting reality actually look like? One such example is by Volodymyr Nevidomyi (whose second name translates to “unknown”). It states that “Volodymyr Nevidomyi lives in a psychoneurological internat (center for disabled citizens) in Pushcha-Vodytsia.[3] Volodymyr is focused more on collecting, rather than creating art. He never leaves his archive, where one can find not only drawings but also medical prescriptions, someone’s awards, packages, a small book by Rilke, a beret, and parts of someone else’s diary. In such form, Volodymyr’s archive can be seen only once, as it moves and transforms all the time.”[4]

The dynamic collection of the works in How Are You? presents a curatorial choice to bring a multitude of anything they could find. The exposition was organized in chronological order: walking from one floor to another, viewers were exposed to the evidence of how Ukrainians have experienced the full-scale war from the first days until the summer of 2023. The exhibition’s abundance, on the one hand, aligns with the overwhelming reality of the ongoing war, and on the other hand, underscores the huge public effort to convey the experiences of trauma, in this case, expressed through art. It showed how art can also serve as a therapeutic tool during wartime, being able to talk about the shocks of the war. These possibilities of talking about traumatic experiences and being heard are crucial points in the theoretical research around trauma and healing.

War creates a high level of unbearable stress that results in various traumatic disorders. Battle fatigue, combat stress reaction, or traumatic war neurosis have been known since ancient times. Freud explored such conditions after his encounter with the World War I veterans in Europe. In the 1980s, the diagnosis of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) was identified after studies with Vietnam War veterans were conducted in the U.S. But how can we talk about our traumas? Some trauma theorists, such as Cate Caruth, identified the “unspeakable” qualities of trauma. According to Caruth, experiencing trauma is marked by amnesia and “crisis of truth” due to the overwhelming quality of the traumatic event and the lack of symbolic tools (language) to understand it. Caruth states that “in trauma the greatest confrontation with reality may also occur as an absolute numbing to it, that immediacy, paradoxically enough, may take the form of belatedness.”[5] This situation then creates the “collapse of witnessing,” as survivors don’t have direct access to their trauma but are possessed and haunted by it through symptoms such as flashbacks, hallucinations, dreams, and acquired behavioral strategies. However, trauma researcher Richard McNally has contested earlier theories, stating that “traumatic amnesia is a myth, and while victims may choose not to speak of their traumas, there is little evidence that they cannot.”[6] He provided much evidence that trauma can and should be described because the very idea of “unspeakability” can be harmful for survivors, and emphasized the need to provide a space and the possibility for creating trauma narratives, as they also have healing power.

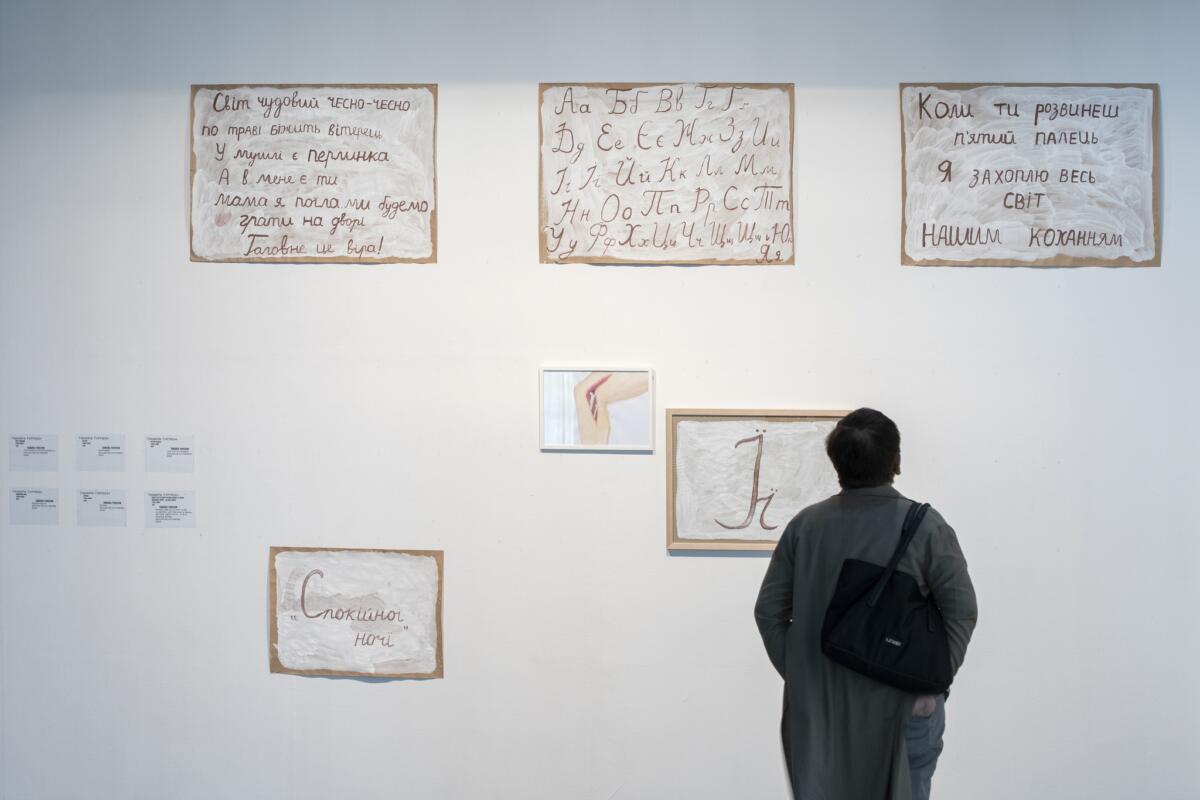

How Are You? has become such a space for the expression of wartime narratives and emotions, from flashback-like metaphors to coherent discourses. There were many texts on the walls as well as incorporated within artworks, there were diaries that brought together visual and text-based parts, or works that consisted solely of text, such as Yevhen Samborsky’s visual quote of folk wisdom: “Everything was divided into before and after.”

Joshua Pederson, recalling McNally’s book Remembering Trauma, states that the origin of trauma is rooted in stress, and stress actually strengthens memory. “Traumatic memories, then, are not elusive or absent; they are potentially more detailed and more powerful than normal ones”; “authors may record trauma with excessive detail and vibrant intensity” and “traumatic memory is often multisensory; victims may record not only visual cues, but aural, olfactory, tactile, and gustatory ones as well.”[7] Standing in the exhibition I felt as if I was surrounded by, in the words of Pederson, “excessive details and vibrant intensity,” which were difficult to process at once.

The exhibition presented many efforts to face the unspeakable. And it is not an easy task, because how can art address the tremendous loss of life of those who are fighting in the battlefields, the murdered civilians, the raped bodies torn to pieces, and the ravaged landscapes of destroyed towns and villages? Some artists try to represent this through symbolic images of anxiety, anger, sorrow, and pain, or hybrids of the ominous reality outside combined with inner dread. These images become symbols of the harsh reality of today’s Ukraine.

In the large-scale panoramic photograph Izyum Forest by Yana Kononova we see personnel at the site who carried out the exhumation of bodies in the mass graves in the city of Izyum in September 2022, after the Kharkiv region was de-occupied. Kononova was present as an accredited journalist. Her camera focuses on the figures and faces of the personnel, the bodies of the victims are beyond our gaze.

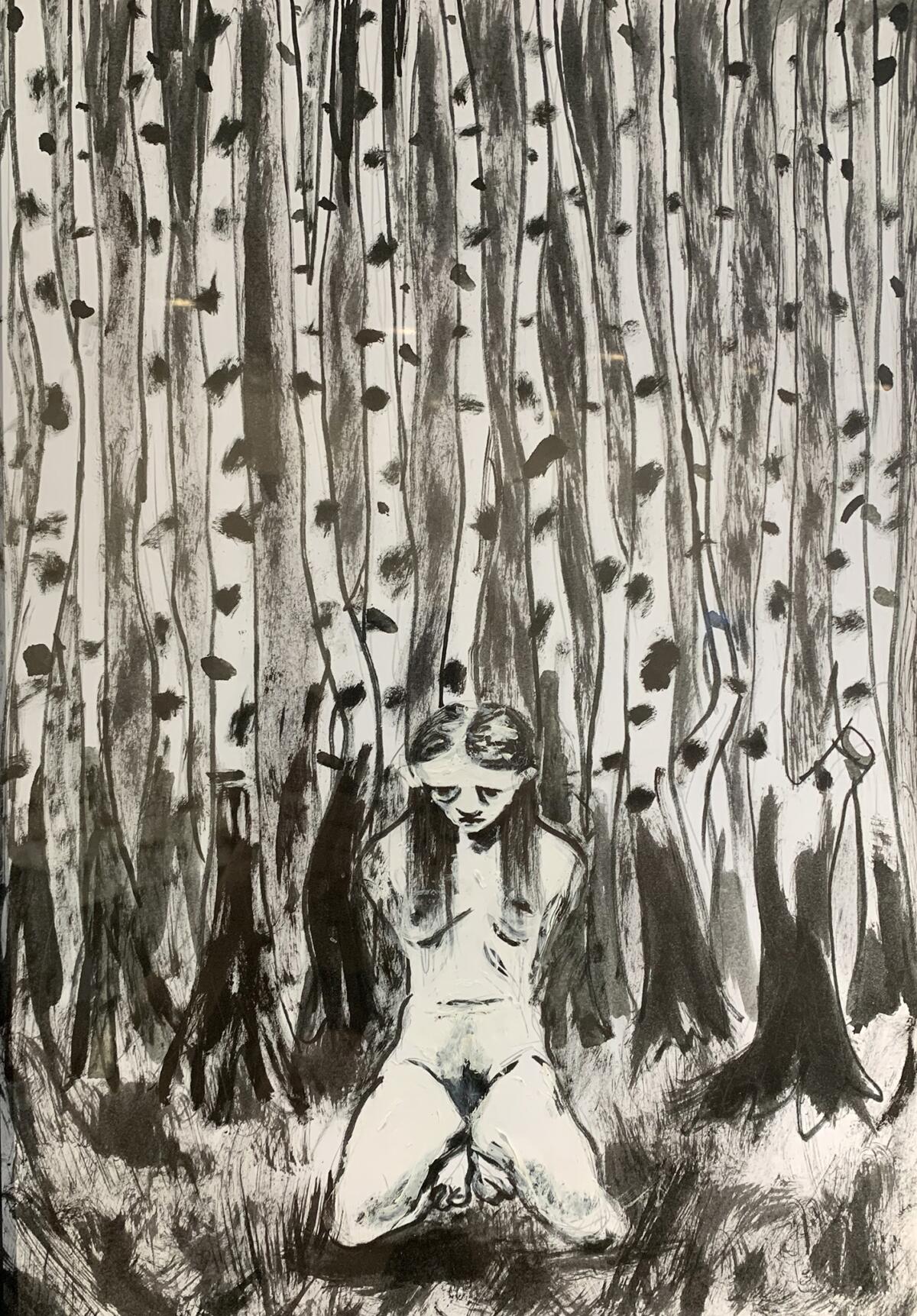

In two of Alina Yakubenko’s drawings we are confronted with a naked male and a naked female body, with hands tied behind their backs, kneeling in front of a birch grove. The landscape becomes a backdrop for the cruelty of war. The bodies are immobilized and static like the trees that stand behind them, both tainted by the actions of the perpetrator. Observing these exposed bodies directly from the front makes us think about the place of observation in which we find ourselves. Imagining the perpetrator, a Russian soldier, looking at them from this same place, is emotionally challenging, so we may also assume the role of a powerless invisible observer, which drives us to identify with the victim, a distressing experience as well.

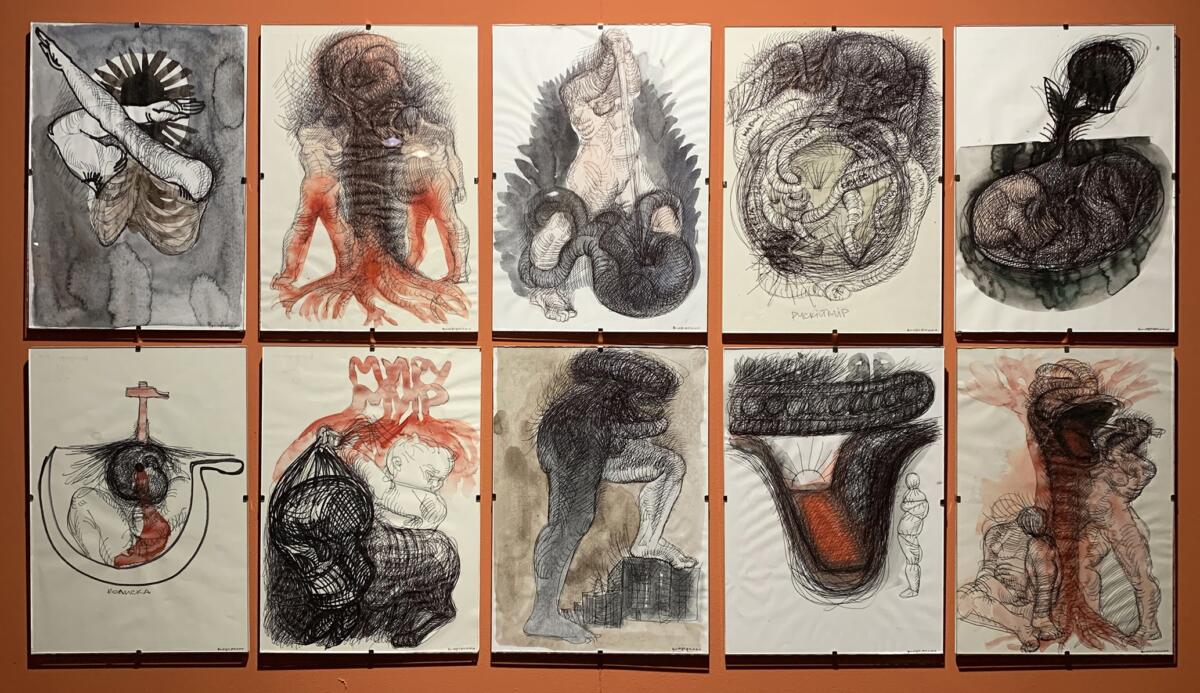

Vlada Ralko’s drawings are metaphors in which the corporal and political have merged together in a suffocating struggle. We see an ideological monster recognizable by a false Soviet anti-war slogan ripening in the cradle, turning into a horrifying poulpe of the “Russian World”, with its tentacles crushing the world and peace. There is the inevitable battle with this monster and its destructive power, the battle with a dragon which takes on a mythical form with the struggling naked bodies, and the use of red within the monochromatic graphics reminds us of blood. But this struggle is devoid of heroic connotations. Instead, the images exude a sense of fragmentation, hallucination, nightmares and horror; the feelings identified in battle fatigue syndrome.[8] The eerie images evoke the monstrous neighbor who not so long ago claimed to be an “elder brother.”[9]

In her painting Ukrainian Garden, Kateryna Aliinyk depicts the corruption of the fertile Ukrainian land; among the fruits and roots there are human bones and missile debris. The artist delves into what lies beneath, which can also symbolize the unconscious, the invisible. It makes me think about what memories about this war might become buried in our minds, what kind of potential dangers we may carry within ourselves, akin to the way the soil, while thriving each new season, will quietly retain toxins, remnants, and debris from wartime.

In Oleksiy Sai’s work Bombed, the texture of war is imposed on a map of the strike territory. The land in the frontlines resembles a sieve, riddled with countless holes and craters. For those who have died, new holes have been dug into the earth to bury them. My grandfather, who was a soldier wounded in the Second World War, had a deep hole in his arm. He survived and carried that hole with him for the rest of his life, though he never publicly brandished it. I observed it briefly when he changed his shirt. What he did share on some special occasions were his orders and medals, of which he had a few. The historical time in which he lived did not afford him the opportunity to speak about his traumas loudly or to display his wounds. The Soviet ideology and its wartime narratives were primarily centered around acts of valor and heroism, which were extensively represented through monuments, books, paintings, and films. My grandfather died and I never heard his personal story of war.

The stiffness of the moments of anxiety or violence in Vasyl Tkachenko’s large-scale paintings are depicted in a mostly monochrome palette. In these images, color appears to be fading and vanishing. This reminded me of the main character in Toni Morrison’s novel Home, featuring the character Frank Money, a Korean War veteran who grapples with a mental disorder that manifests itself in sudden, harrowing flashbacks. When these episodes occur, the world around Frank literally loses its colors. These moments become dissociated from reality.[10]

Through Tkachenko we observe moments that are dissociated from our ideas of normal reality before the war, belonging instead to the reality which is unfolding now. We see two male figures from behind, in casual clothes, focused on something near a door with glass panes. What are they doing there? Those who lived through air strikes on their cities can guess that maybe the men are strengthening window glass with a transparent tape so in case of an air strike the glass will remain strong. The two figures look so alike that we may think that this is one person splitting apart, like a twofold reality that consists of dreadful danger and ordinary routine. In another painting we see two figures, a man sitting and a woman lying down in the darkness. They are illuminated by a strange light. Their bodies as well as their gazes are frozen in waiting. The darkness around reminds us of a basement, maybe they are sheltered during an air attack. Two other paintings depict immobilized bodies on the ground. In one of the images, the crowd is running away stepping over the body, and in another the dog is licking the body, sniffing death. We don’t see any blood or wounds there, so we are not convinced of what is going on. This uncertainty increases the viewer’s anxiety about the depicted reality, like if we don’t know for sure but are guessing the worst. The artist gives us room for interpretation by eliminating all additional details from the paintings and naming works only with dates when these events occurred.

This was my blind reading of Tkachenko’s paintings. Later I found out about the artist’s process, which consists of several stages. A filmmaker from Mariupol, Vasyl Tkachenko stayed in Lviv in 2022 while his family remained in the occupied city of Mariupol. Vasyl didn’t hear from his family for a month and half while the Russian atrocities took place in the city. He started a series of paintings, preliminarily staging the scenes from stories heard from people he knows or that he found on the Internet, some of them were based on what had happened to his family members in Mariupol. The people who performed the reenactments were the artist’s friends or sometimes the artist himself. Photos of the scenes were taken and were then translated into paintings. Tkachenko notes, “The process of creating a painting and its performative aspect is no less important for me, as a final result. Through this action, which I might call performative painting, I imagine my personal body as collective, and the narrative I construct as an archival document, a recording of a moment in history that can be read both personally and collectively.”[11] This remark refers to the collective nature of war trauma, and the way in which individuals, including artists, are involved in that experience. In his analysis of collective trauma, Gilad Hirschberger says that “…identification with this symbolic collective entity is, therefore, vital to the management of the terror of death, to the extent that the memory of the collective becomes one’s own memory; the aspirations of the collective become one’s own aspirations; and the pains and woes of this collective are experienced as genuine personal suffering.[12]

In many works, the intensity of the content existed alongside the constraints and simplicity of the materials used for their creation. When you are required to go to a shelter, or are waiting to be evacuated, you must think about the most important things you can take with you if you might have to leave your previous life behind. You might only bring documents, bank cards and some cash, a phone and laptop, chargers, medicine, some clothes and underwear. If you are an artist, you may also pack a few art supplies in your bag; paper and markers, maybe a small watercolor set or a few tubes of acrylic paints. Such simple materials possess the ethical equivalent of that which is valuable, and this criteria is a part of the difficult decisions that have influenced the aesthetics of many of the included artists’ works.

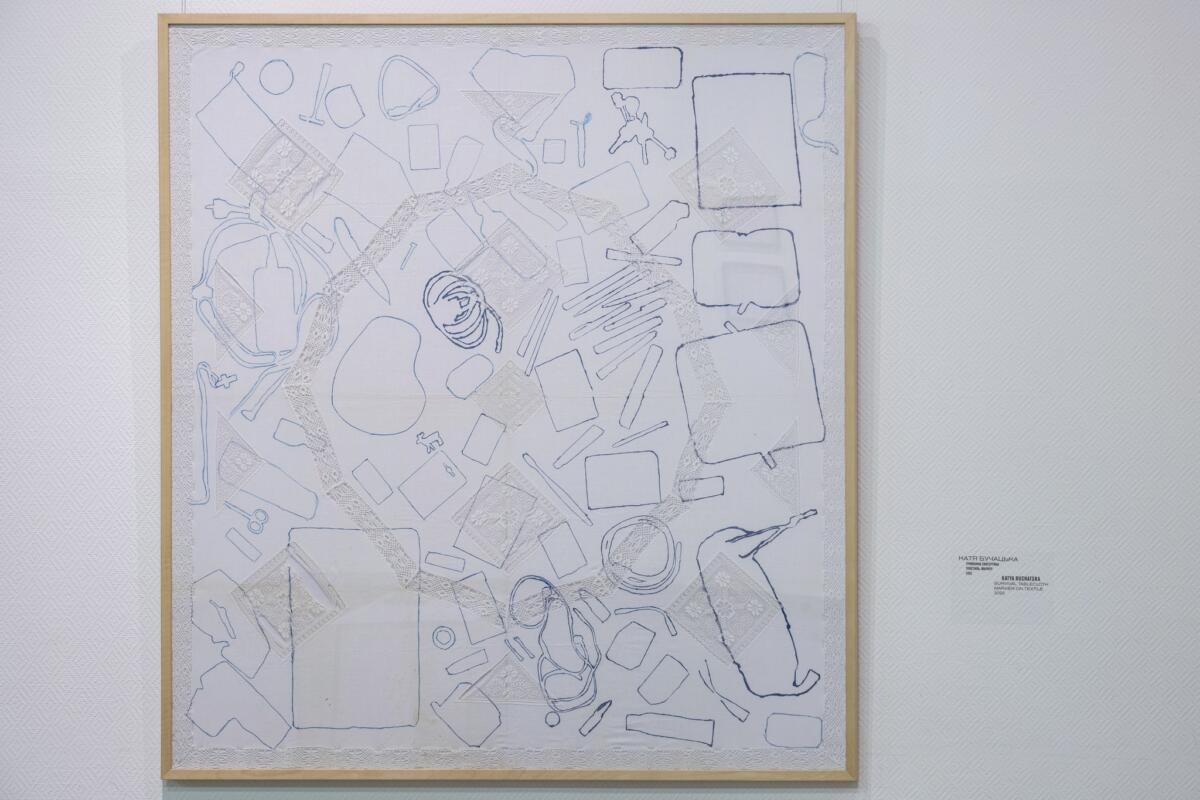

In Katia Buchatska’s Survival Tablecloth, the artist meticulously outlined with a marker, each object she put on the tablecloth. These objects are the essential items that would be packed in an “emergency backpack,” a “survival backpack,” or an “alert backpack”—all potential translations of the Ukrainian term used to describe the bag you grab when you have to flee immediately.

Polina Polikarpova’s self portrait offers another possible translation: “disturbing suitcases”. “Air alert” literally translates from Ukrainian повітряна тривога as “air anxiety” or “air disturbing.” So the Ukrainian title of Buchatska’s work translates literally to “disturbing tablecloth.” In her photos, Polikarpova is seated in an armchair with the bags in the next chair, into which all the essential items fit. Her self-portraits shared similarities with the selfies that some of my friends were posting on social media at the onset of the full-scale Russian invasion: non-smiling, fatigued, gaze directed straight into the lens. Polikarpova also includes interiors which hold significant meaning: the living room with its decorations that bear the imprints of the past and generations that might have to be left behind at any moment, or the corridor, the safest place in the apartment during air strikes, due to its load-bearing walls and absence of windows.

The description of Mykhailo Alekseienko’s work tells us that the artist entered a building destroyed by a Russian rocket and met a man who lived there. In this apartment, the artist discovered shattered crystal glasses, once decorative objects often found within the sideboards of the older generation. The man allowed him to take these remnants. Alekseienko depicted them in watercolor and exhibited the drawings on a piece of wall paper that likely matched the interior of the ruined apartment.

In these drawings, according to the artist, the glass shards cast shadows reminiscent of the debris of Russian shells. The artist captures a dialectic of destruction; the object that destroys also inevitably destroys itself. The artist, much like an archeologist, explores objects that just yesterday played a role in someone’s life only to become part of the ruins today. Life has been turned inside out, transformed into death. There’s no attempt at restoration; instead, the broken everyday objects serve as symbols of fragmented memory, constructed from the debris of a previous life.

There are a large number of people in Ukraine who are not on the battlefields and not in exile, but who continue to live in the country experiencing the tensions and uncertainty which has now become everyday. They live in a gray zone between abnormal and an unattainable normal. Even though they may not be actively involved in war physically, mentally it is inescapable. Art, such as the works included in this exhibition, creates a portrait of Ukrainian society today – people’s lives which are regularly interrupted by air strike alerts while trying to live “normal” lives.

On one of her paintings from the Am I? series, Nata Levitasova scratched, “Just try to act as you are normal.” In this series she attempts to adapt the body to the sharp lines of hedgehogs, or anti-tank barricades, which can be seen everywhere now in Ukrainian cities.

Though the sound of the air alerts have become commonplace for Ukrainians, it is still hard to get used to it. The painting of a woman driving by the artist Kinder Album is framed by the repetition of the Ukrainian letter “У,” which creates an onomatopoeic expression of a prolonged siren howling, “У-у-у-у-у-у”. The waves of its sound, visually written, also strangely resembles barbed wire. Barbed wire segregates territories and designates them as especially dangerous zones. One can drive to the border and right after crossing it, can embrace the ease and calmness of the sky beyond Ukraine. A friend of mine told me that only after finding herself abroad has she fully comprehended the harshness of the reality at home. The sharp forms of the anti-tank barricades contrast with the forms of human bodies and the barbed wire designed to mangle human flesh.

Zhanna Kadyrova appropriates hand-embroidered decorations for the home that she first found in a village in Zakarpattia, which she started collecting for her series Air Alert. This type of popular folk embroidery is usually performed by women and typically depicts nature or unpretentious scenes that include people, deer, swans, and other animals. It is associated with domestic coziness and the nostalgic idea of home. In the context of war it can also remind us about ordinary people, those who produce these embroideries in rural areas who don’t have resources to flee to foreign countries. At the top of these pieces, Kadyrova applies a kind of stamp executed with a sewing machine with the words “air alert” (повітряна тривога). This stamp signifies an interruption, a cancellation of the pieceful routine which now can be destroyed at a moment’s notice. Air alert is a foreign intrusion into this imagery, but what is remarkable in Kadyrova’s works is that the initial images remain undistorted. In the same way ordinary people keep living their lives even while there are air alerts.

Another work by Kinder Album that illustrates the “new normal” is a self-portrait from the blackout period. On that tiny drawing dated October 19, 2022, one can read, “When there is no electricity, no water, no internet, and no phone connection, but there is gas, I make myself a coffee.” This journal-like drawing reminds us that during challenging times, routine and small pleasures remain important and can somehow contribute to the meaning of being alive. I make coffee for myself as a way to keep going and to not give up. Kinder Album often incorporates nudity in her work, and many of her pre-war pieces explored themes of sexuality. However, during war, nudity has taken on a new meaning, representing not only extreme vulnerability and honesty but also, paradoxically, strength.

This exhibition, as well as other exhibitions that take place now in Ukraine, are in themselves gestures of courage. Can safety be ensured for both art and its viewers in Kyiv today? They are safe until a Russian missile hits the building. The probability of this is not that high since the air defense system works effectively in the Ukrainian capital, but such a chance is still real as air attacks on the city are regularly occurring. When I left the Ukrainian House after viewing the exhibition, the wailing siren drowned out all other sounds on the street.

What could feel more important than protection in a time when destruction is all around us? Archives are intended to preserve the stories of our lives for future times and generations, and contribute to the construction of the collective self. It’s common knowledge that art cannot combat invaders, and there’s nothing more urgent than actual weapons for defending our lives. But art does play a role in safeguarding. And in the case of collective trauma, such as war, the preserving of memory has, according to Gilad Hirschberger, several functions. “The memory of trauma, however, serves the needs of individuals and groups far beyond its contribution to survival; the memory of trauma and the existential threat that is inherent to it motivate a desire to construct meaning around the experience of extreme adversity. In this process of meaning-making, a transgenerational collective self is pieced together.”[13]

Edited by Katie Zazenski

[1] The curatorial team included Yehor Antsyhin, Olha Balashova, Halyna Hleba, Yuliia Karpets, Anna-Mariia Kucherenko, Katia Libkind, Tetiana Lysun, and Oleksandr Soloviov. The project took place as part of the Post-War Memory Culture in Ukraine program, implemented by the MOCA NGO in partnership with the Memory culture platform Past / Future / Art, with the support of Switzerland.” https://moca.org.ua/en/main/

[2] From MOCA’s facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/MOCAORGUA

[3] The neighborhood in Kyiv.

[4] From the description in the exhibition.

[5] Cathy Caruth. Introduction to Trauma: Explorations in Memory. The John Hopkins University Press. Baltimore and London. 1995. P. 6.

[6] Joshua Pederson, “Speak, Trauma: Toward a Revised Understanding of Literary Trauma Theory”. Narrative, Volume 22, Number 3, October 2014, Published by The Ohio State University Press. P. 334.

[7] Ibid. P. 33.

[8] Flashbacks of “battle fatigue syndrome” are described as “highly dissociated, dream- or fugue-like states, with little or no ability to communicate them in words.” Dori Laub, Nanette C. Auerhahn. Knowing and Not Knowing. Massive Psychic Trauma: Forms of Traumatic Memory. The International Journal of Psycho-Analysis; Apr 1, 1993. P. 292.

[9] In the Soviet ideological discourse, Russia asserted itself as the “elder brother” to all the “brotherly nations” within the other Soviet republics, openly emphasizing Russian dominance.

[10] Richard J. McNally describes “dissociative alterations in consciousness” that are often observed in traumatic memory: “Time may feel as if it’s slowing down. Spaces may loom. The world may feel unreal, or the victim may slip outside his or her own body.” Joshua Pederson, “Speak, Trauma: Toward a Revised Understanding of Literary Trauma Theory”. Narrative, Volume 22, Number 3, October 2014, Published by The Ohio State University Press. P. 339

[11] From Vasyl Tkachenko’s notes shared with me by the Ukrainian Museum of Contemporary Art / UMCA.

[12] Gilad Hirschberger. Collective Trauma and the Social Construction of Meaning. Frontiers in Psychology. August 2018, Volume 9.

[13] Gilad Hirschberger. Collective Trauma and the Social Construction of Meaning. Frontiers in Psychology. August 2018, Volume 9.

Imprint

| Exhibition | How Are You? Exhibition and Discussion |

| Place / venue | Ukrainian Museum of Contemporary Art / UMCA |

| Dates | 1-25.06.2023 |

| Curated by | Yehor Antsyhin, Olha Balashova, Halyna Hleba, Yuliia Karpets, Anna-Mariia Kucherenko, Katia Libkind, Tetiana Lysun, Oleksandr Soloviov |

| Index | Anna-Mariia Kucherenko Halyna Hleba Katia Libkind Oksana Briukhovetska Oleksandr Soloviov Olha Balashova Tetiana Lysun Ukrainian Museum of Contemporary Art Yehor Antsyhin Yuliia Karpets |