What are the limitations or conflicts of the (co)existence of human and non-human entities? What tools can be employed to resist authority? The group exhibition, Horizons of Autonomy at Knoll Gallery, discusses the challenges of autonomy through a range of mediums and approaches, to address issues that have been relevant in the past and that continue to be significant today, not just within the Hungarian context but globally as well. By analyzing our relation to autonomy, we can gain insight into our fundamental psychological need for self-governance, comprehend the intricate dynamics of our social interactions, and recognize our ties to the state and how that affects our autonomous self. Some of the works on display in the exhibition reflect on the connection between individual needs and authority, for instance, when the autonomy of an institution (like a university) is compromised by the influence of an authoritarian state. Other pieces discuss acting against violence in the context of autocratic leadership or threats of individual autonomy in capitalistic systems. A need for sensitivity and empathy when it comes to authority, which is another major underlying topic of the show, is highlighted through vulnerability in a hospital environment, particularly for women during childbirth, or the demanding of empathy and representation for marginalized communities from authority figures. This dissonance and lack of understanding leads to necessary demonstrations, such as the protests in Hungary, Belarus, and Russia. It is crucial to bring attention to the parallels in the political landscapes of these countries, and to position Hungary within this context, and to emphasize the growing right-wing trend in the government. It is also important to note that there are not many art events reflecting on or criticizing this turn in Hungary. With hope for the slightest change, open discussions and a sense of community are essential. This exhibition encourages a collective approach, portraying important both group and individual resistance strategies.

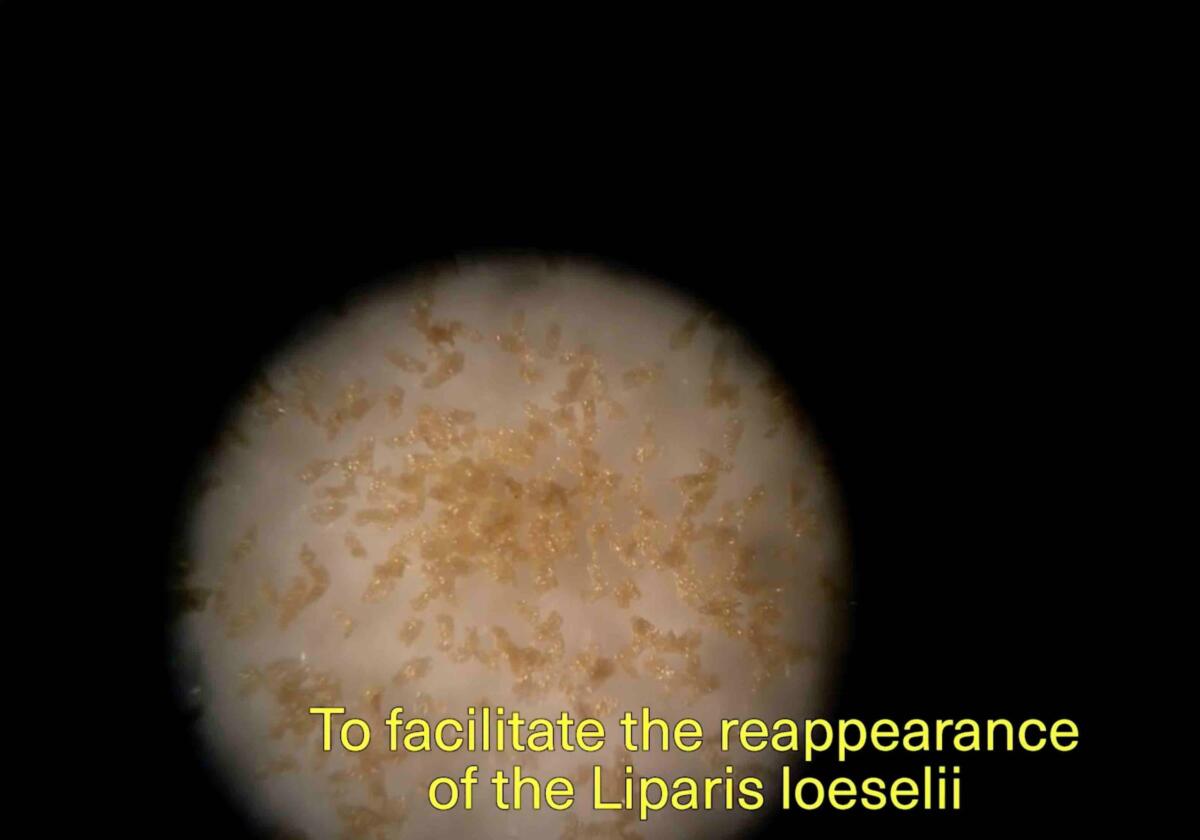

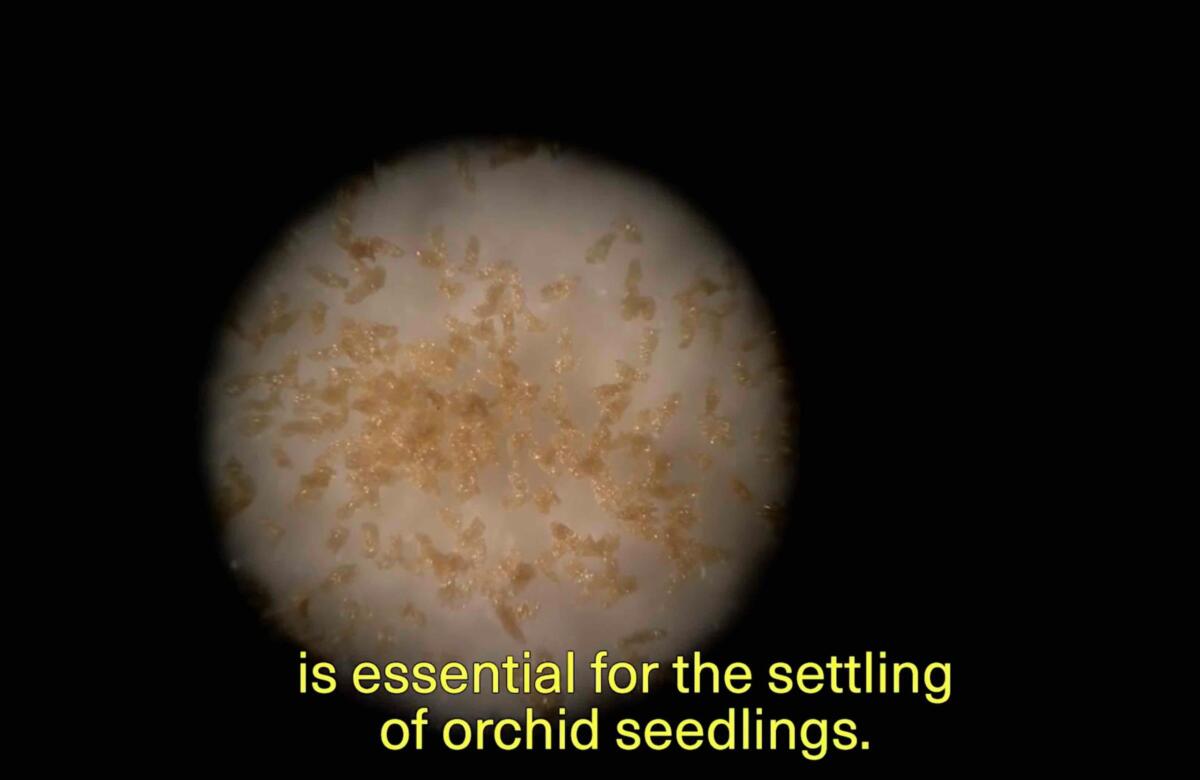

Entering the first room, we come across Hanna Rullmann (NL) and Faiza Ahmad Khan’s (IN) 16-minute video Habitat 2190, documenting the construction of the nature reserve Fort Vert, which was built on the site of the former migrant camp “The Jungle” in Calais, France. The short film explores how nature can be used as a tool for controlling borders, and addresses complexities when it comes to the co-existence of human and non-human life on certain land: the contrast of the protection of rare species and the disregard for humans seeking refuge through migration. What we find is that the possibility for living beings to coexist in a single territory is not given, but rather a consequence of agreements. South America, India, and New Zealand have taken steps to give entities of nature like rivers or lakes “environmental personhood”, providing these non-human entities with a new set of rights, making them harder to harm, and representable within the legal system. This topic still has some unresolved questions, like whether or not this could protect nature in reality, and who will be in charge of representing these entities, or the question of the clashing rights of human and non-human entities.

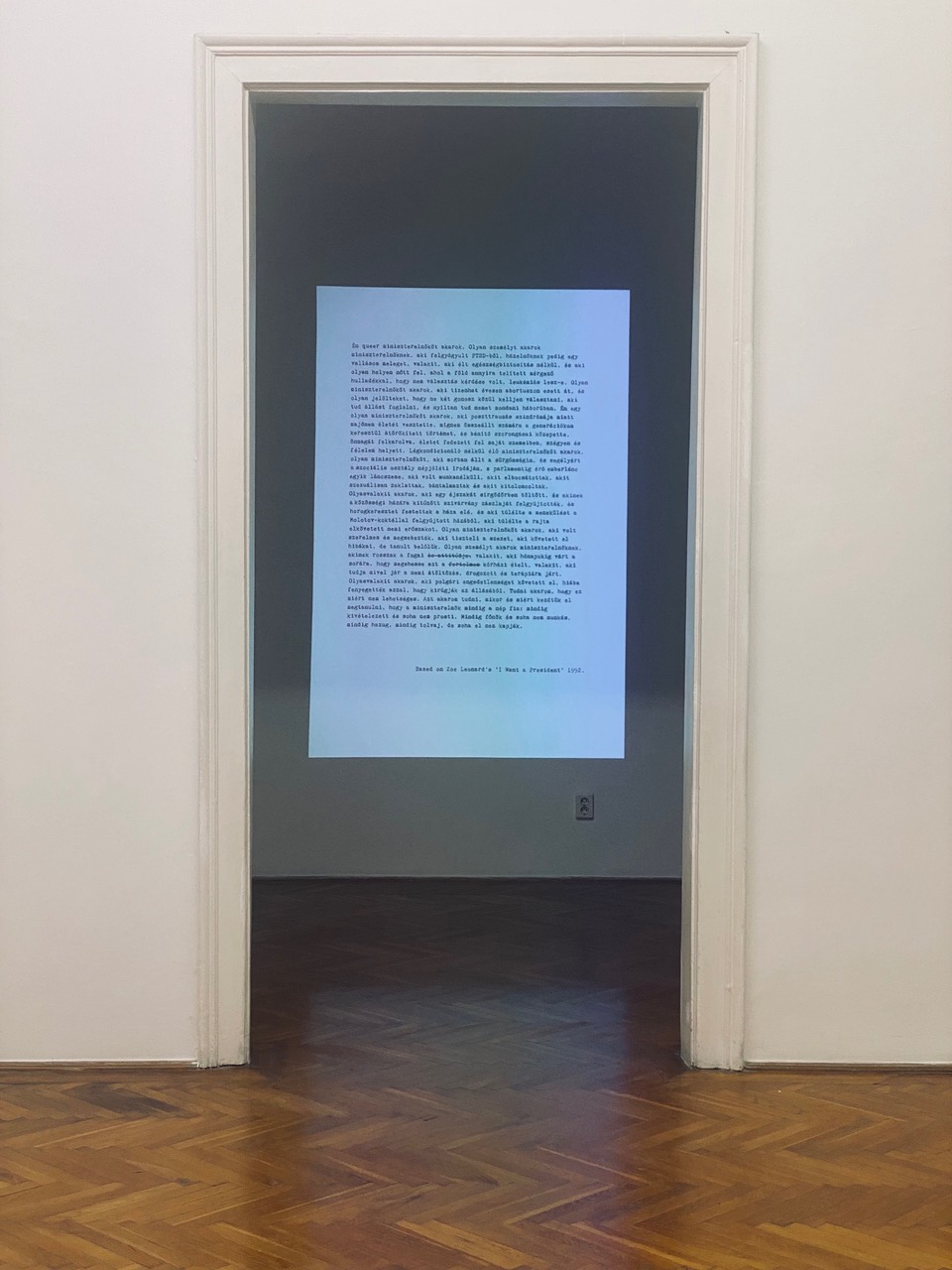

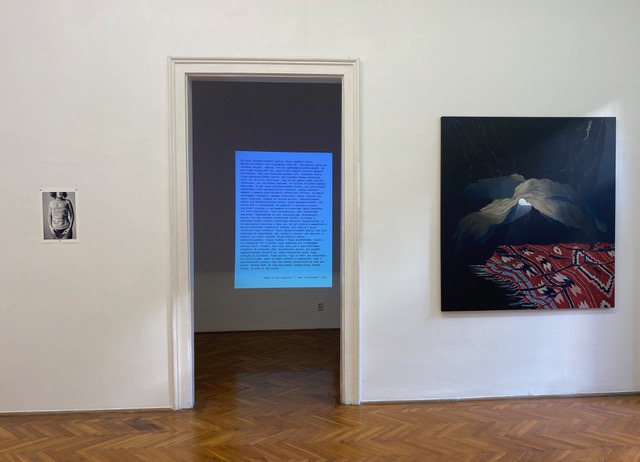

Zsuzsanna Szegedi-Varga’s (HU) adaptation of Zoe Leonard’s (US) I Want a President… (1992), discusses what we look for in leadership and who we want to advocate for our individual and collective interests. Since its origin, the work has been displayed, published in a variety of locations, and reimagined by other artists. The 1992 text has moved beyond its original form of being a political text to being present in popular culture, through social media and other everyday contexts. It has even been used as a spoken word piece. It was originally produced when the poet Eileen Myles ran for president, as an independent, alongside George H.W. Bush, Bill Clinton, and Ross Perot during the 1992 US presidential election. Since then it has resurfaced in more recent elections: a large-scale version of it was installed in New York during the 2016 cycle which is now famous for seating Donald Trump. But there is also relevance to it in the recent elections in Hungary and Turkey. Accompanied by an English translation and with printed versions for visitors, the work in this exhibition creates another level of connection between the artist and the audience, resulting in a nuanced and personal interpretation of the material.

Artists in the next room, Alice Hualice (RU) and Lázár Todoroff (HU) both tackle the topic of autonomy through their performative and demonstrative approaches reflecting on the impact of institutional and governmental pressure. According to the curator Erzsébet Pilinger, Hualice’s Name the Country (2020) is a visual representation of a question she was asked during an interview, “In which country would you like to live?” Her response is depicted in the artwork: Hualice appears in the Kremlin, multiplying herself wearing otherworldly textile masks bearing enlarged features, reflecting on her position of being present now in Russia. Her art focuses on creating an otherworldly realm, incorporating mystical elements, grotesque figures, and altered textiles. However, recently her platform has been used to address the war crimes perpetuated by Russia in Ukraine. In the past year, she demonstrated her response to the war through a performance where she walked through her hometown of Nizhny Tagil carrying a sign with the powerful message “No to war”, confidently declaring her stance. This statement resurfaced again in her artwork as she stitched the message onto a black coat, accentuated by blue tears on the back, and a split, bleeding heart on the front. The role of power and authority also emerges in Lázár Todoroff’s piece in which he documented the 2020 FreeSZFE movement in Budapest, where individuals protested against the institutional changes at the University of Theatre and Film Arts, which was placed under the governance of a private foundation and given a new board of trustees (which was founded directly by Fidesz). As a result, students and teachers occupied the institution to demonstrate their endorsement of self-governance and independence. The occupation became a symbol of resistance and a collective approach to university autonomy and intellectual freedom. Todoroff’s Tableaux Vivant – Delacroix: A Szabadság vezeti a népet (2020), acts as a solidarity action amongst the art historians who stood outside of the university building on Vas Street from which this image was taken.

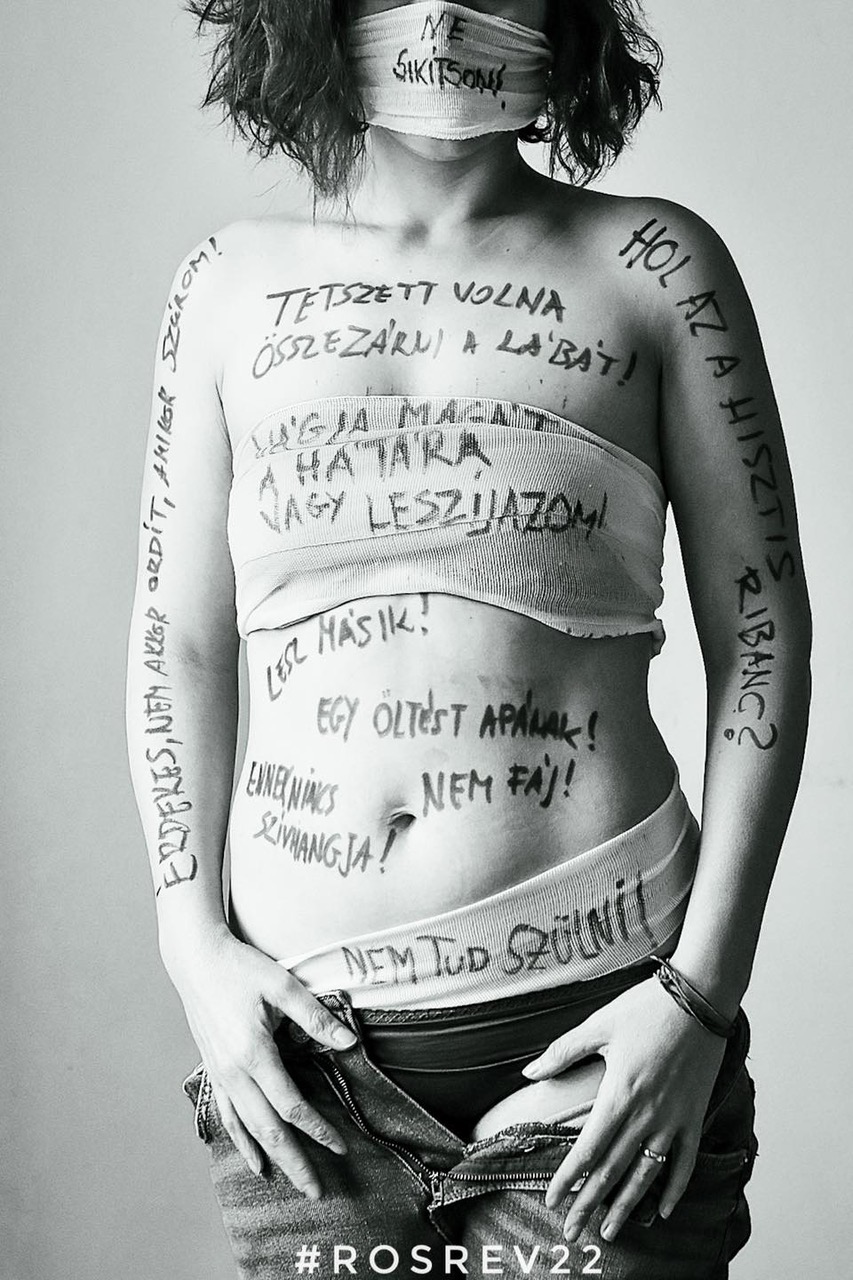

Gender norms and the instrumentalization of femininity or masculinity are other central themes we can find in the exhibition. Gabriella Tuboly-Vincze’s (HU) Rózsák forradalma (2022/2023) is a powerful commentary on obstetric violence. Tuboly-Vincze, an ethnographer researching trauma, used her own body as a platform for displaying the offensive phrases that her interviewees heard during their experiences of childbirth (“Do not shout!”, “You cannot give birth” or “It does not hurt”). The photograph can be interpreted as a call for women to speak up and express themselves, emphasizing the importance of women’s rights and the various threats to our autonomy: increased restrictions over reproductive health and rights and the threat of losing a job after maternity leave. Tuboly-Vincze’s work can be interpreted as a demonstration, providing space for discussion on this continuing public health crisis.

Attila Bagi’s (HU) series Big Boys Don’t Cry (2021) highlights the expectations of gender expression and how harmful that can be on our mental health. Bagi’s paintings move along the border of figuration and abstraction, mixing colorful motifs and figurative depictions inspired by elements from his childhood. The deliberate placement of Zsuzsanna Simon and Gabriella Tuboly-Vincze’s photographs in proximity to Bagi’s paintings initiates a discourse on the expectations of gender roles by exploring how autonomy over our bodies and personal identity can be distorted by external societal influences. Zsuzsanna Simon’s (HU) photograph in the third room of the gallery also deals with issues surrounding expectations placed on the female body, focusing on strict beauty standards which often lead to a distorted sense of self. Simon’s series Ugly or Beauty (2018) questions these societal expectations of women, and takes on the question of hair as the source of her scrutiny. She has been researching hirsutism, a condition that results in excessive body hair growth which affects many women. Many of Simon’s works aim to generate awareness and dismantle the established ideals surrounding women’s bodies. Her series features images of female body hair embellished in various ways. She also creates pre-made pieces for those who do not have body hair, which acts like “jewelry” and can be worn in different settings – to a party, to the beach, etc. She names the images according to the occasion to which the piece can be worn. Techno (2023), currently on display, showcases embellished armpit hair with glitter, crystals, and fake eyelashes. The pink frame, made specifically for this exhibit, reinforces the question of femininity, almost acting like a mirror, suggesting that this work is also a self-portrait. The artwork is a reflection of how societal expectations amplify the experience of living with the medical condition and how that can significantly impact how women feel in their own bodies. By exaggerating and emphasizing the body hair on her photographs, the artist challenges the traditional notions of femininity and highlights the diversity of women’s bodies, aiming to deconstruct insecurities and encouraging a reevaluation of their expectations.

Continuing with the topic of identity, the works of Rufina Bazlova (BY) address her views on autonomy and desire for democracy in a way that is both grounded in tradition and relevant in the contemporary context. Bazlova uses traditional Belarusian embroidery patterns to reflect on her country’s fight against the current government, and for freedom and democracy. Her embroidery first gained attention when the pro-democracy protests for free elections broke out in 2020. She reached back to a time when embroidery was a women’s only way of communicating their experiences, through unique, geometric symbols. This work acted as a way of coding the history of Belarus in a symbol set that was traditionally used only by women. The colors of the embroidery hold important symbolism as well, with red symbolizing blood and white symbolizing freedom, referring back to when the country gained a certain level of autonomy in the early 90s after the Soviet Union collapsed. These colors, also the colors of the Belarusian flag, became a symbol of an independent Belarus and a Belarusian identity that was distinct from Russia. The three embroidery prints showcase the ongoing political struggle in Belarus and document real stories of resistance. Bazlova’s works evoke questions such as to what extent can individual and collective identity be manipulated or limited? What are the possibilities of art being used as a tool in protests or resistance against oppressive systems?

This exhibition highlights the power of collective action towards change. The works included challenge harmful ideologies, prompting us to question contemporary authority and the inconsistencies that appear, especially related to gender. The exhibition goes beyond human entities and explores non-human bodies as well, examining their relationship to autonomy and what implications this holds for human entities, or vice versa. These works encourage us to reflect on the various threats that can compromise our autonomy in relation to institutional and governmental impact, problematic figures of authority, as well as our own connection with our bodies. The artworks also emphasize resistance against these violations, highlighting art’s presence as a form of protest, or the importance of community in standing up for something, even when the tangible impact may not be immediately apparent. Despite some negative connotations of previously failed attempts, there is an ongoing pursuit of collective resistance recognized, with the hope that its long-term impact and success lie in increasing visibility, raising awareness, and pressure enough to gradually shift public opinion and lead to policy-based change.

Edited by Katie Zazenski

Imprint

| Artist | Rufina Bazlova, Attila Bagi, Alice Hualice, Zoe Leonard/ Zsuzsanna Szegedi-Varga, Hanna Rullmann és Faiza Ahmad Khan, Zsuzsanna Simon, Lázár Todoroff, Gabriella Tuboly-Vincze |

| Exhibition | Horizons of Autonomy |

| Place / venue | Knoll Gallery, Budapest |

| Dates | 23.03 - 12.04.2023 |

| Curated by | Erzsébet Pilinger |

| Index | Alice Hualice Attila Bagi Erzsébet Pilinger Gabriella Tuboly-Vincze Hanna Rullmann és Faiza Ahmad Khan Knoll Gallery Budapest Lázár Todoroff Rufina Bazlova Zoe Leonard/ Zsuzsanna Szegedi-Varga Zsuzsanna Simon |