Prologue and discussion with Albertina Viegas.

La’o Lemorai on the occasion of a residency at Municipal Gallery bwa Bydgoszcz, 6 November – 8 December 2020

John von Sturmer: You know that I hate the idea of artists having to explain their work – or intentions. I am not the least interested in anything that smacks of ‘justification’ – or the inquisition. And the notion of cause is, at the end of the day, pretty much bound to fall short of any useful contribution to the art work. The art work is free-standing – not that it stands alone but it is, yes, a lonely space, a space of aloneness. It is this that gives it a certain exemption… There are two central notions that apply to your situation: the notion of displaced person(s) and the issue of grief. The arrival of the DPs (non-British European migrants) in the aftermath of WWII does not represent a new moment in history except in the most narrow sense; Australia was in point of fact a society of displaced persons. Even the ‘timeless people of the timeless land’, its indigenous populations, are as often as not deemed to be displaced, disinherited, ‘removed’.

Speaking generally the reality of displacement threatens (threatens to threaten) – but may be liberating. Suddenly we discover ourselves in unfamiliar surroundings. We become the alien – but at the same time we may find ourselves in a sort of celebration of our otherness which suddenly may come to us as a boon and not as something to regret or to repudiate. It is the commitment to stasis – ‘unchange’– that is the problem – or so I think. The repudiation of history and historical circumstance may constitute the real killer blow – and the destruction of possibility … In reality there is no clambering back. The trick: how to be at home in the absence of home…

Lying in bed trying to think what and how I should write about you. About you? What a funny weird notion. I know you too well and not at all! My thinking such as it is is to think of a series of displacements. In my own case being displaced from my home town, a mid-sized city, turned out to be addictive: new start, new start, new start. The small town we were ‘ejected’ to came as such a surprise – and I loved it. My home town now appears as a backward, redneck land – dull and fading.

So how old were you when you were forced to flee Dili? What was the ‘ordinariness’ of your life up to that time? Children have a way of creating whatever environment they are in as the ordinary: the taken-for-granted – good and bad and indifferent…

Albertina Viegas: Displacement 1 – I was 8 years and nine months when we left for Oz [Australia]. We left our home in Faról, a seaside area of Dili, around brother Fern’s birthday. [East Timor declared independence from Portugal on the 28 November 1975. 9 days later the Indonesian military occupied the former colony.]

Dad came home that day from his workplace, the Portuguese Banco Nacional Ultramarino. He told us that he’d heard people were gathering at the big sheds at the wharf nearby us. We could go and seek refuge there for a few days. Maybe there was a way to leave Dili from there.

The night before, I remember sleeping on the ground under our dining table. A number of other family members like my godfather had fled his home and was with us. Perhaps our area was safer, even though there had been a lot of gunfire during the night. I remember a lot of noise and commotion.

Mum and Dad on their wedding day, Dili, c. 1957, photographer unknown, courtesy Viegas Family Archive

We left home carrying very little with us. One of my cousins came with us. My godfather had decided to go back to his house to find other members of his family. When we were at the wharf, my mother had instructed my eldest brother Vic to go back to our home to get some nappies and things for Bea who was a baby at the time. It was interesting what he finally decided to bring to the wharf – a whole suitcase of Mum’s kain-batik and kabaya (women’s clothes traditionally worn). He had also brought our cassette player/recorder with a tape of songs in English I still remember to this day.

My mother said, we had no idea where we were going to. We went to the wharf waiting to die.

The big shed at the wharf stored canned food and ceramic goods. I recall them being moved aside to make room for the big crowd that was now assembling at the wharf. We slept on the floor and had very strange food; I think I may have even been drinking from cans of condensed milk of which there was a plentiful supply. We remained there for a number of days. A cargo ship out at sea that was transporting goods from Bali to another island had picked up our distress signals and came to evacuate us. We were in the hundreds.

The scene on deck as 272 East Timor refugees (mainly Portuguese) arrive in Darwin aboard the ship MACDILI – NT, 1975, image courtesy of the National Archives of Australia. NAA: A6180, 18/8/75/23

Do you recall your thoughts on the boat? Did the boat have a name?

Displacement 2 – We were shunted from a small light boat at the wharf in Dili to the Norwegian freighter, the Lloyd Bakke which stood offshore further out to sea. The crew was Chinese. These scenes on the boat that day continue to give me grief even now.

At the edge of the wharf, there were men in army fatigues searching our bags before we were lowered onto the little boat. I recall Mum saying to one of them clearly, ‘Eh Anó, as if there’d be any artillery hidden in my child’s nappy bag’. He insisted on rummaging through everything. So many things were going on, a lot of noise and confusion. Artillery fire was going off left right and centre. Only women and children were allowed to leave. We had to leave Dad and Atoi behind. My brother Vic had to take control. I don’t know how he and Mum must have had to take that news. That was hard but we had to accept it there and then. Atoi had been part of our family for a long time. He was from the Atsabe region. He had helped Dad in all manners possible, delivering his lunches, errands, and doing many things around the house. He also helped Mum with all the cleaning. Sadly, he died in tragic circumstances a couple of years ago which I might have told you about. A tragedy that bears heavily on our family.

When we were hoisted up one by one to the ship, I remember looking down at the sea which seemed a long way down and really deep. I have that same fear when I can’t swim and tread water when I’m in a deeper part of any water. The boat journey was not easy. The Chinese crew were handing out bread rolls. My cousin was sea sick and she couldn’t help me. I was lining up a number of times for others in the family to get this bread. I do remember being hungry. I also remember, when I looked back, when the corner tip of the island started to get smaller until I couldn’t see it anymore. That’s the time we were thinking, we had left our home behind. Who knows when we would see our home and our families again.

I am of course intrigued by your response to the ‘new country’. Did you stop/stay in Darwin? How did you encounter it – and your response to Sydney, suburbia, school, learning English, whether you had any sense of having moved from the centre of Timorese society to the ‘fringes’ here, no longer at the centre …?

Displacement 3 – We were out at sea for many days, that’s how it seemed. When we arrived in Darwin, it took about 5 hours or so before we could get customs clearance and allowed to dock. It must be early morning before we could go on land. I remember listening to the soppy songs in English being played on my brother’s cassette player while we waited. Was it Neil Sedaka? Or maybe his contemporaries?

Darwin was bright. The light seemed very bright. I think we stayed in some tents out of town, perhaps on stretchers. Some were staying in rooms which I remember were all white. Maybe it was near Howard Springs. I remember seeing and meeting people from other families. We who became the 75ers. We chose to go to Sydney and could fly out in a matter of days. Flying on a Hercules was really something. The loudness and the size of it. And the smell and sickly sweetness of yellow banana-shaped lollies they gave us on board.

Sydney was freezing cold. I thought it was the coldest place on earth. They gave us these grey blankets to put around us as we got on buses to take us to Cabramatta Hostel. I attended Cabramatta West Primary School and was placed in English classes with all the others who had travelled with us. Some were much older including my brothers. I learnt really quickly. After only a few months they moved me to normal classes. I was put in 3rd class. All the others remained in that class for some time longer.

We were in Cabra for some months. We were moved to the Westbridge Hostel in Villawood. I attended Chester Hill North Primary School. I made friends easily. I had a friend called Cheryl Priest. She was very smart. I remember everything about her, what she wore, how she talked. I remember her saying, ‘Gaw’ blimey, he hit me in the eye’, as she pulled off her glasses to show me her face one time when a boy had accidentally struck her with a handball. Together with a Laotian boy named Khan, I remember being given the responsibility of setting up the PA public address system on the stage for weekly school assembly gatherings. We even had to adjust the mic and mic stand for individuals of varying heights when they came to present or address the assembly. Even when our family had moved to Yennora, at the primary school there I was asked to set up the mic and PA for school assemblies. Our family was one of the first to move out of the hostels into the community. We were more willing to be sociable outside of Timo [Timorese] networks and get in to the new Australian lifestyle. We embraced it where others didn’t. We each had many groups of friends. I loved school, especially when it became noticeable that home life was beginning to pose various challenges. I was really good at school. My first teacher at Yennora Primary School was an African American called Mr Childs. He was very encouraging and promoted me to 4th class after being in his class for not long. I apparently had good handwriting and often had to take my bookwork around to every teacher in the school to give me a stamp. I felt privileged and free. I did really well in my subjects and was good at art and sport. I played netball and softball and loved athletics. I was the sports captain for the Gold Team and partly responsible for making up its war cry which they still chant, apparently … Thunder thunder thunderation, we’re the best team in the nation. Gold is the colour that will beat, all the other teams we meet. G-O-L-D, yeaaaaay GOLD!

My family was into sports in a big way – cricket, soccer, football – rugby league and Australian Football League – volleyball, softball, basketball. Dad was keen on wrestling – but no cockfighting!

J.W.C.Adam, Asylum seekers protesting at the Villawood Detention Centre in Sydney, 22 April 2011, image courtesy of the photographer, license: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.5 Generic

That makes you a good Ozzie-bite, sports crazy! The sine qua non of Australianness! I remember you telling me about working as a cleaner – when in Dili I presume you had people to do that sort of work.

Yes, as I think I mentioned, Atoi cleaned, Bou Vicente ironed and Abí Maria washed our clothes. There were so many of us kids. We needed all the help we could get. They were like family members and helped look after us together with our aunties and uncles who raised us.

By the time I finished studying art at Penrith, besides waitressing jobs, I was cleaning 3 places in the city who had the same owner, including one venue close to your place at the Cross. An artist friend from the city – artist in reticence, she called herself – passed on this job to me as she was sick of cleaning. At that time, four of us had started Street Level ARI in Penrith in 1988 and we each needed to come up with money to pay the rent, electricity and other expenses. Katie Soady spearheaded our efforts and did an enormous amount to get us going. Luckily when we asked Con (as he was known then) and others in his last year to join us later on it brought our membership to 30 which made it much easier to pay the rent of 300 per month. In Aug 1988 I had the first show opening of the gallery with my domestic weapons installation in one room and a video projection of a performance at Paddington Markets in the second shop front window which you could see from the street…

And how did you make the transition to art? Were there any key influences? Were you a ‘rager’? Was there a sort of freedom in not really being a local – though part (an unconscious part) of the great migrant influx and the attendant de-anglicisation …Cabramatta as the ‘new land’ … the end at least temporarily of White Australia, as an official or unofficial doctrine…

I have a vague memory of playing some games in the yard at our place in Dili, including making mud cakes and mud roads and playing with our piglets, which gave me worms… We had white pebbles in our backyard which we would try and create sparks with, some flints – fun attempts at making fire. I also remember once doing a drawing/painting of some hens, a rooster, a dog (with poo coming out of its backside) and a tall tree with many branches with a bird’s nest. The animals were behind some fence or an enclosure. My teacher thought it was really good and asked me to make a bigger version of it for public display. I think I was 7. I remember often drawing on bits of paper and making little Mother’s Day and Father’s day cards (Para Mãezinha e Paizinho) with inscriptions and little drawings of flowers. I always remember the smell of pencils, colour pencils and paper when I was little, which gave me an indescribable pleasure.

In the schools I attended in Australia, I spent a lot of time in the art room. So much so that the teachers would often give me keys to be there whenever I felt like it. The art teachers were always supportive and encouraging of me and my work and going to see exhibitions was deemed necessary for our practice. I always had a close association with my art teachers. Whether I liked them individually or not, for the times I felt forced to learn things about myself or in developing art skills. They treated me with respect and thought I had something to offer. The art room was, after all, like a second home to me. I loved learning about everything and being at school. I learnt to make and paint large scale banners that hung in church for different occasions.

John von Sturmer & Christine Olsen, ‘Uma Lulik & Katupa Soldados, Tuba-rai Metin’, installation, Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, still from film recording Feeding the Katupa, 1996, courtesy John von Sturmer & Christine Olsen

And the decision to go to art school?

There was no question about that. Earlier on, I looked up to my brother Fern for his drawing skills, even after he chose music (and soccer) over art. When I was 13, I was asked to enter a Catholic School poster competition to do with St Benedict. I remember drawing and painting different scenes of St Benedict’s life. I often had to crouch on the ground to do homework late at night after all my domestic chores and duties. I may have been painting and doing homework in the dark at times. Anyway, my 2 year-old brother who I helped raise since he was born on my 10th birthday, managed to spill some black ink on the completed artwork. Drats. I had to make use of the ink blotches and rework the images and handed it in. To my surprise, I won first prize. And earned my first 50 bucks.

Tell me about your progression into the art scene, your tertiary training, group shows and exhibitions, student activism, your participation in the 1988 Sydney Biennale… Such a memorable year coinciding with the Bicentenary, the two hundred years of European colonisation… It was as I recall a year of historical triumphalism and fervid nationalism – but not without significant counter-movements of protest and critique and challenges to the historical record…

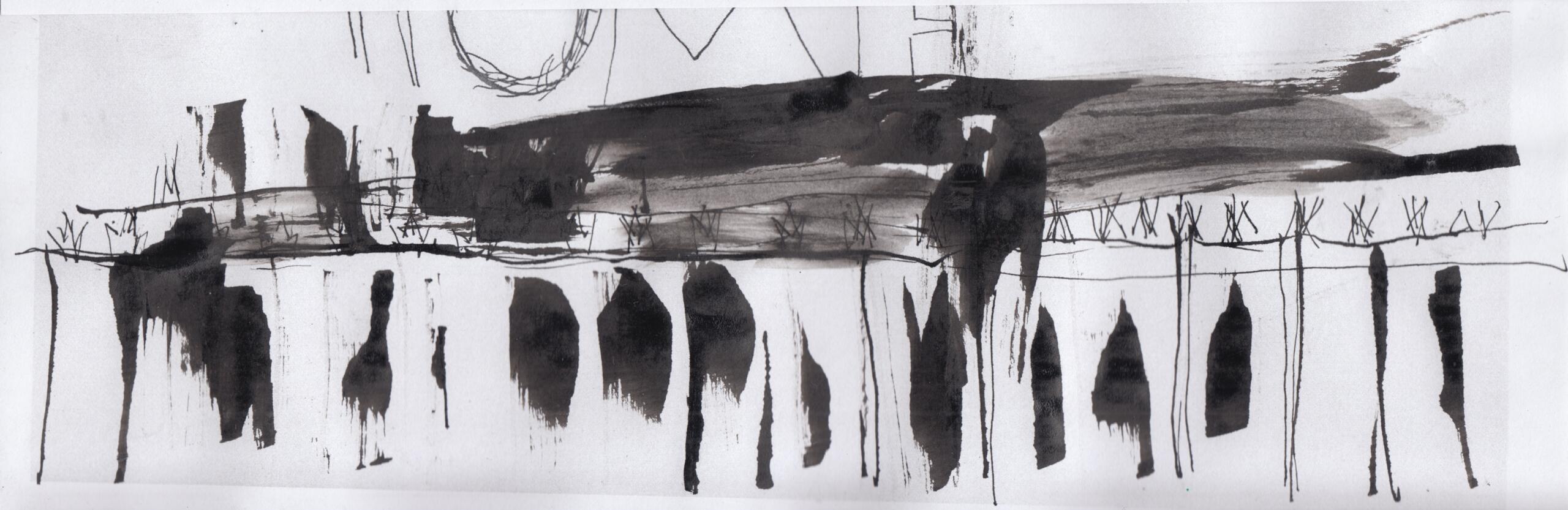

Yes… From 1985–87 I attended Nepean College of Advanced Education in the far west of Sydney. Later it would become the Western Sydney University. There was a conspicuous British presence in the Arts Faculty. I soon gravitated to sculpture in which I majored. Drawing and experimentation formed a strong foundation for everything we did and I especially enjoyed working on large scale stone axehead drawings. I engaged with many different media – bamboo, wood, metal, other and found materials, natural and unnatural.

Our sculpture group was a gang of 5 girls: 2 from rural NSW, one Italian from Merrylands, one Macedonian from Yagoona and me. Nothing came our way that we couldn’t handle. We gave a hard time to others – principally the painter crew. Studying women in art with Catriona Moore and women’s studies boosted our confidence, our self-regard. Our exposure to different art forms was also extended, for example, through an exposure to Islamic Art. In retrospect I’d have to say we were apt to throw our weight around. We truly believed our art-making was superior to that of the painters, certainly from a conceptual angle. We worked hard individually and formed a tight-knit group. Our sculpture lecturer Noelene Lucas instilled a strong work ethic and supported us in every way imaginable. We interviewed established artists and identified with them strongly. We also discovered Eva Hesse and Louise Bourgeois … When Noelene was on leave in our last year, Bonita Ely and Cheo Chai-Hiang kept our creative spirits strong.

We learnt to weld (oxy & arc) with the boys from Mount Druitt Tech. We made excursions to Transfield in Seven Hills where we were fortunate to be given offcuts of steel which we readily incorporated in our work. We forged working relations with fellow student sculptors from Prahran, in Melbourne and went on numerous field trips to make environmental art. During this time we had our first encounter with performance art and installation. The Arte Povera movement was an important motivation: poor art, poor students – that was us! Our studio was in a new industrial complex in Penrith. There was a second hand shop nearby with super cheap clothes and lots of suitable material for making sculpture, together with a supply of material sourced from Reverse Garbage. The pub around the corner was where we’d share a counter meal before heading straight back to work.

John von Sturmer & Christine Olsen, ‘Uma Lulik & Katupa Soldados, Tuba-rai Metin’, installation, Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, still from film recording Feeding the Katupa, 1996, courtesy John von Sturmer & Christine Olsen

My first real meeting with international artists came in my second year. In 1986 I volunteered for the Sydney Biennale and worked with the German painter-sculptor Norbert Prangenberg. Wolfgang Laib made his installation with yellow pollen in close proximity to Norbert’s work. I found this mesmerising! Miriam Cahn’s Wild Loving drawings made me hungry for such a passionate working with charcoal. Her talk with the late curator Nick Waterlow was equally spellbinding. I had been interviewing Hilarie Mais and was drawn to her ocular sculptures and able to experience it first-hand in a show and to talk to her about it. When I started to develop my own art practice, Nick came to be supportive and encouraging of my work at the Ivan Dougherty Gallery. I spakked, sanded and painted I don’t know how many walls at Pier 2/3 for the event.

The 1988 Biennale in the Bicentenary Year meant a further escalation of wonder and inspiration. I worked for Hermann Nitsch at one end of the wharf; at the other end there was Djon Mundine’s landmark assemblage of 200 painted hollow log coffins (dupun), marking 200 years of colonisation. Yes, 43 artists and Djon as curator/coordinator. When I took a break from the Nitsch space on the other end of the pier, I came to this forest of poles. I didn’t know Djon then but he asked me to count if there were indeed 200. Later this dazzling work would be placed on permanent display at the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra.

For the graduation exhibition I created an installation-performance entitled ‘There are more than [so many] ways of Overcrossing the Sleeping Crocodile’. In 1985–86 I curated a student show – my first exhibition – at the Upcake Art Gallery next to the Fairfield School of Arts. I had lefty journo friends who were running it as an arts/music/writers meeting place. We organised music gigs: a subculture of quasi-mods, rude boys, skinhead types, listening to ska music, punk-rock, new wave mod revival music of the 80s and into social change music and culture. We looked towards the UK for inspiration. I’m not sure anyone has done a study of Fairfield in the 1980s. We were a motley crew at times but an interesting little scene to be on the edge of things, all these different nationalities but becoming anglo in their interests.

Around the same time, I was heavily involved in political campaigns for East Timor – lobbying government and influential people, prominent supporters like Phillip Adams and Bob Brown, the Greens leader. I was not aligned with any partisan politics of ET and actively worked to support the ‘resistance’, working with both sides and later to support CNRT initiatives. My sister Cissy was also involved and brother Fern was an influential musician in the community; he was involved in the grassroots reggae scene. My brothers were all musicians and played at many Timorese gatherings; six of them were in a band at one stage and gigged also at the Fairfield School of Arts. I was invited to sit on committee meetings with UDT party heads in Sydney. They were grooming me to be their cultural attache. These were difficult and confusing times that tested our allegiances. There were splits even in the family. On a practical level my personal activism extended to film-making and photography. In 1990 I curated a photographic show in Fairfield entitled East Timor: A Photographic Perspective 1974–1990…

John von Sturmer & Christine Olsen, ‘Uma Lulik & Katupa Soldados, Tuba-rai Metin’, installation, Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, still from film recording Feeding the Katupa, 1996, courtesy John von Sturmer & Christine Olsen

Tell me about Street Level …

Yes, an early artist-run initiative. I was no doubt galvanised by the ‘underground’ experimental/free improvisation scene in Inner Sydney in the late ’80s. Around 1986–87 I organised a series of improvised music and performance workshops for the late Ryszard Ratajczak, Brett Nancarrow and Alan Schacher at Nepean. This served as a rehearsal for concerts and performances held later on at Street Level. Street Level was a mix of high energy, enthusiasm and trying out things for the first time. Susan Norrie was our first big name artist to have a show at the gallery during her artist’s residency at the university.

We showed ‘Minymalu Kanyirranytja’, an exhibition of Ngaanyatjarra women’s wooden and metal bowls and digging sticks from Warburton Ranges in Central Australia. Around this time, I met the Ngaanyatjarra ladies M. Lawson, Lalla West, Mintjaya Ward, tjitji kulurpa Minyma Lisa and senior custodian Mr S. Davies. M asked if I could come and work with the ladies at Ranges, whispering to me in that desert way of drawing the breath in as she spoke.

We campaigned and did artwork for East Timor, with a focus too on Aboriginal issues and local matters in Penrith. Later we moved to Blacktown where we pursued similar issues. And then there was Kon’s opposition to animal vivisection …

John von Sturmer & Christine Olsen, Albertina Viegas with Tia Veronica Pereira Maia, Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, still from film recording ‘Feeding the Katupa’, 1996, courtesy John von Sturmer & Christine Olsen

Is it reasonable to suggest that all this energy and commitment to political causes arose as a consequence of the Whitlam Revolution (Prime Minister 1972–1975)? We had of course before that the anti-apartheid movement which can easily be seen as a precursor or co-driver to the Aboriginal land rights movement… This was the era of self-determination which is where East Timor comes into the picture…

In 1989 Pope John Paul II said mass in Dili (see New York Times, 13 October). This was the first time there was an international focus on the Timor situation. But the real turning point for me and others in the struggle was the Santa Cruz massacre of 12 November 1991. I found the full footage of the video recorded and smuggled out by the journos who had witnessed the event shocking when I watched it for the first time a few days back. I’d only ever seen a short edit. Over 270 mostly young people mown down. Back in Australia it triggered the public art project, ‘Tuba-rai Metin: Firmly Gripping the Earth’. This travelled from Darwin to Circular Quay in central Sydney, on to Casula in Sydney’s west and then to Canberra and back to Sydney again at Customs House at the Australian Museum just before independence came in the form of a referendum. It made its long journey in a sea container – as though it too was escaping across the waves … An 8 metre uma lulik (sacred house, a scaled down replica), 21 katupa soldados (soldiers) woven from strips of lead and matched to my size. These were essential contents of the container along with the Tais Don (see below).

In my own art practice, I had long wanted to honour the lives of those who had died in East Timor since 1975 and had thought of learning to weave tais, the traditional Timorese woven textile, in order to record the names. The tais reminded me of woven war badges with insignia. I wanted to contribute to the struggle in my own way, not only through protest and active campaigning, but to try and make sense of it all, for my own purposes. I was one of the lucky ones living in the shade of Aboriginal country, rai nain sira. I had managed to get out alive. How could I make sense of this?

In the course of my research I joined Amnesty International and went through their reports and files in order to compile the names of people. In my first return trip to Timor around 1990 when we were allowed entry as visitors, I sourced my own weaving apparatus for a backstrap tension loom. I had insisted on learning and received demonstrations by the Atsabe ladies who were squatting on our family property behind my aunty’s house in Dili. I had travelled to my father’s country and learnt about the terracotta ceramic vessels made from local clay. I learned about the palm weaving basketry techniques of Maubara, a village in the Likisá district, speakers of Tokodede.

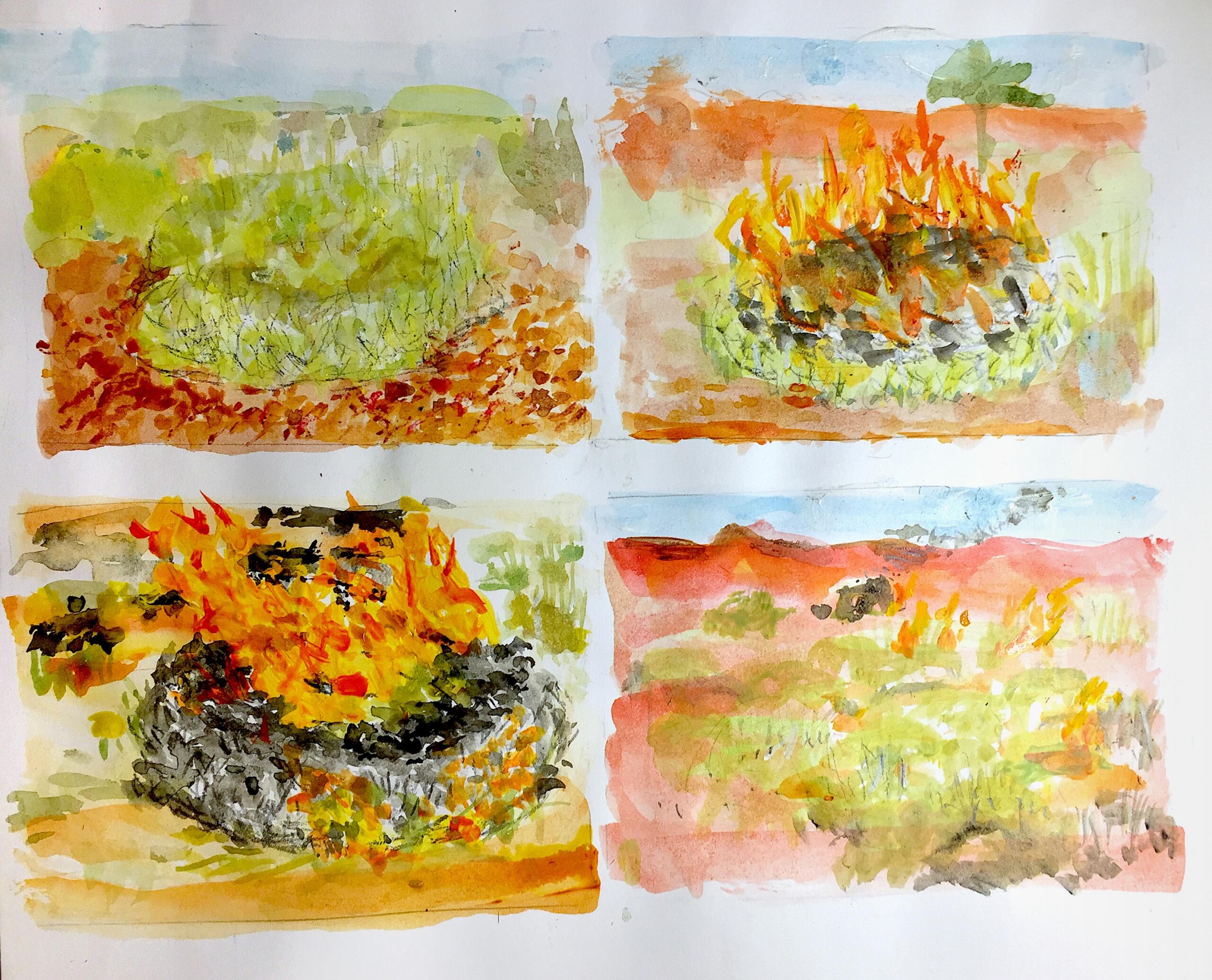

Albertina Viegas, ‘Bush fireworks, the spinifex explode… Whoomp!’, 2020, acrylic polymer and pencil on paper, photo courtesy of the artist

In Sydney my mother had instructed me on how to weave the katupa, coconut rice parcels. We had relatives in Darwin who would send her fresh coconut palm leaves in the mail and she would make them for us on special occasions. She was often making them on our return trips to Timor. I noticed that one of the katupa forms was in the shape of a hand grenade.

Afterwards, I met Dona Veronica in Darwin and I better understood the complexity of the weaving process… That’s it. I learnt that I wasn’t able to do these names myself. I began to create a script on grid paper of the names of the victims of the massacre and understood that she was the only one that could do it. The gravity of weaving such a heavy load would only be for someone of her seniority.

Returning to Dili for the first time was a big trial. It was hard getting there and even harder to leave. I had to return to the day I had left as an 8 year-old, on that wharf. I had to face it, I had to face that moment. When we drove past the wharf, my stomach would go into major convulsions and I wasn’t able to breathe. I made my relatives drive me past our old place which had been occupied by other families and I would turn my attention to it, driving by, feeling something lost. As soon as we reached the wharf, my tummy would churn and a major panic would overcome me. This happens still to this day when I visit and when I think about it.

I could only have returned to Dili after being in the desert. Going to the desert in Warburton was like going home. Home in a big sea far away from everywhere and everything else. That mob in the desert, they gave me home. Everything was connected there, people were huddled together in a society that was close, intimate, intimately known; they brought me in, they embraced me, teaching me about myself as much as who I was, as well as who and what I wasn’t. I felt fully connected to and with them. This was something that I didn’t experience living in a place like Sydney. In the desert I felt more myself than I had ever felt before. Anywhere else.

The desert was a critical and rewarding period, life-changing…

Displacement 4 – Living in a wiltja (a traditional bough shelter or shade) in Karilwara. Other wiltjas nearby. Watching the sun’s pink eyelid open up in the morning. Making a fire. The shape of the wiltja is protective, enclosing, shielding our backs. Out front the welcoming hearth. Mama (my ‘daddy’) Mr Ward was there close at hand. Waking up early, yaarlpirri time, when all the old people are broadcasting things, pronouncing on the right way to do things, how to act properly, how to settle disputes. Get up, make a cup of tea, cook damper. Going hunting with Aunty Pulpuru. What a hunter! I’d carry my crowbar across my back, mimicking her, a little bag hanging down ready for whatever we’d manage to hunt. Quickness and efficiency, these were her trademarks. There was no shortage of tirnka, goannas. She’d read the tracks, seal off whatever hole or holes the goanna had entered, find where the ground was loose underneath and then dig and pull it out. Whack! She would whack it across the crowbar, put it in the bag and off we’d go to the next place, all the way giving me a running commentary on what was going on, this way, that way… She knew the country inside out, every place.

One of her special tricks was burning the spinifex, a spiky highly inflammable grass that grows in clumps. In the right wind conditions she’d strike a match into this or that clump. Whoosh, it would go off like an explosion. Not that the burn was uncontrolled; to the contrary. It was like a bush fireworks display.

Robert Kerton, a ring of spinifex grass on fire during a controlled burn, image courtesy Robert Kerton, CSIRO, license: Creative Commons Attribution 3.0

I loved living there with all that Karilwara mob. A steady almost unruffled rhythm of life. Such an assured and confident knowledge of country. No humbug. We’d get up, have something to eat, go hunting, come back, tend to the fire, cook tirnka in the ashes. My favourite was the tail part.

Late in the day I’d watch the eyelid of the sun go down, blue and go to sleep. It was like this day in day out. I loved it.

When we were painting, it was always a surprise to watch a cluster of dotted colours appear on the canvas. We had applied a paint retardant to slow down the acrylic paint drying too quickly. Every painting was a revelation. And boy could she paint! That inimitable Pulpuru style!

I remember when I wet the sponge and wiped the dirt and dog footprints from Mawalingku Ward’s first big two metre painting. I was blown away by the colour and shapes. Waterholes and water snakes leapt from the canvas. You felt you could dive straight in. A first-off yet such an assured work! One of the many works acquired over the years by the Warburton Arts collection, a community-based initiative (‘Warnampi Tjalpu-tjalpu’, 1991, Warburton Art Collection #015(L)).

One time Aunty Pulpuru obtained her own tractor – for collecting firewood and hunting. She would drive it around with Yinkimarta, her skin sister-in-law, and the dogs in the back trailer. There is this hilarious story told by Aunty one time about when they saw what they took to be a UFO flying in the sky. With the tractor still moving, one of them was taking pot shots at it. This story has echoes of the British Blue Streak interballistic missile testing that occurred in the Western Desert during the 1960s. Kurntili mob were out bush and were being rounded up by government patrol officers. The aim was to clear ‘the lands’ for fear of rocket debris falling from the sky. It was the first time she and others had seen a European.

Displacement 5 – After leaving Warburton just after Bubby was born, I came to Poland. It left like another forced removal for me. It was to be a separation from a home I loved.

Albertina Viegas, ‘Magic clouds: ice in the river at Kozielec’, 2019, still from film projection ‘790 (river marker’) in performance with Janka Viegas-Janicka, Jon Tarry & Grzegorz “Pleha” Pleszyński, Mózg, April 2019, courtesy of the artist

Yes, and involving a dramatic shift from a world in which everyone is known and knowable, in which everyone is related, to a world that, at least in its urban manifestations, is characterised more by its anonymity than its familiarity; from a world where rainfall and water are the scarcest commodities, where it is ludicrous to talk of rivers or streams, to a land of rivers that are permanent, ponds, lakes, ice; a dry land of immense distances and endless rudimentary roads scarcely imaginable in the Polish context; wild camels roaming the sandhills against the domesticated herd…

Was the new land a land of promise – or a land of exile?

I’ll take that on notice!

At present we are on the move. Here we are off to Warsaw. Qba has a gig at Spatif. The girls are in the backseat armed with their laptops. I’m in the front, tied to my laptop also, typing the last lines of this text. Sławek’s at the wheel. He loves driving and chewed up the roads of the Western Desert when he was there. Bydgoszcz to Warsaw is pretty much the same as Sydney to Canberra. What is it that makes a city a capital city? Canberra is a contrived city – a compromise between Sydney and Melbourne. A ruined sheep station, according to one wag. The Italian ambassador thought it was a farm. Warsaw we have a sense has risen more organically – but is that true? Bydgoszcz doesn’t feel like a satellite city; it feels like itself.

History arises; history floats, drifts, frizzles away. We have a little house by the river, not far from town. I have a garden. It grows everything. In Timor I had a garden, too. I don’t know that it was exactly mine. In Sydney my mother had a garden – in Yennora – with chooks – Cabra, Saddo. In Warburton I had a garden; between the heat and the lack of rain it thrived when it could. Here my garden overflows, luxuriates – but the winter cold is never far away.

I wonder if I’ll ever get used to the cold.

It seems a long time from when I first appeared in this neck of the woods. It was a large art event, called ‘Construction in Process’. First in Melbourne then here where I met Sławek. I performed a little ritual at the edge of Lake Foluski in Ostrowce. How am I to think of that now, as an act of immersion? Ritual gathers up the past but inscribes history in the present moment. Does it freeze or congeal things? My little event involved a spoken hamulak – a prayer offering – in three languages: English, Tetum, and some Polish. My Polish still remains inadequate; maybe it isn’t as bad as I think but it’s not good. My two girls are fluent locals, totally at home.

A girl always in a rush, that’s how some of our friends describe you. Always late as if you must cling to something in the now, as if there is nothing more important or urgent than that actual moment of doing and thinking… It is true, is it not, that the child remains but comes to each new circumstance ‘innocent’. The child is also old worldly, a strange conservatism. The child does not like disruption…

Can I answer indirectly? It may be true. Christmas is just around the corner. In Warsaw I expect all the Christmas decorations will be up. In Warbo one Christmas we set a shade in the garden under a grapevine, with water pouring from a sprinkler and wetting the canopy. It was heavenly. Christmas in Timor was different – a time of family and relations. At my father’s workplace, he was the Santa Claus who handed us presents for Christmas. My sister Cissy was terrified of anyone in a Santa suit… In Poland we could I suppose sit outside in the snow with a big fire raging nearby, yet we are inside…

The club – MÓZG – and my kids and my teaching are at the centre of my life. My parents and brothers and sisters are far off and it’s not easy to communicate. With the virus travel is pretty much out of the question. People here ask, Dlaczego tak poważnie? They seem to demand something ‘positive’. What’s this, L. Ron Hubbard time? Serious things demand serious response, not casual distraction or wishful thinking.

I think about the future – for the kids I teach, my own daughters, my partner, Babcia and the family here in Poland, my absent family in Australia, Timor, Portugal and beyond, the people of the Western Desert and Clutterbuck Hills. If regret is in order let there be regret. If there is stuff to grieve let there be grief. There is no sin like false positivity. Let the real be dealt with realistically. I hope I am a realist – and ready to take on board whatever form the next transformation will take.

Glossary and Notes:

Villawood: (opened 1949 during the height of postwar immigration) was a migrant hostel. Later with the shift in and hardening of government policy towards migrants it became a detention centre for inmates who had overstayed their visas and for ‘illegal’ boat arrivals. Figures prominently in the public imagination. A site of frequent protest.

Villawood, Yennora, Cabramatta (‘Cabra’), Merrylands, Fairfield form a cluster of suburbs in the ‘grand banlieu‘ to the south-west of Central Sydney. St Mary’s is in the extreme west – about an hour by train from the CBD. Its nearest centre is Penrith. It is here that Albertina and her mates created Street Level, an artist-run initiative, in Penrith. Later that would move to Blacktown. Cabramatta affectionately known as Cabra has something of a cosmopolitan (or at least racy) reputation with its large Vietnamese population (more boat people!) and other ethnic groups. The principal religion is Buddhism.

Con: Kon Gouriotis, formerly director, Casula Powerhouse Arts Centre and Director, Visual Arts, Australia Council for The Arts; currently editor of Artist Profile.

Bea, Cissy, Fern: siblings of Albie, along with Vic, Dom, Tony, Charles and Andy, still living in Australia. Another brother Manuel lives in Dili where he seeks to maintain his family’s pre-Indonesian property and other interests.

Fretilin (Frente Revolucionária do Timor Leste Independente), UDT (União Democrática Timorense): prominent Timorese political movements. CNRT (Conselho Nacional de Resistência Timorense) was a non-partisan strategy aimed at creating a platform more focused on national rather than political ideology.

Maubara: a village, not be confused with Maubere, a Portuguese term of derision applied to the ordinary folk but taken up by Fretilin as a revisionist, populist move.

La’o Lemorai: To travel outside one’s place of birth, going from place to place; and a longing for home.

Warbo: a shorthand way of referring to Warburton. Founded in 1933 as an offshoot of Mount Margaret mission. Since 1993 it forms one of the 10 communities which fall under the umbrella of the Shire of Ngaanyatjarraku. The shire headquarters are located in Warburton. Sometimes referred to as Ranges.

The skin system: In common with much of Aboriginal world the Ngaanyatjarra have a moiety system which effectively divides the world into two halves; in this case sun-side and shade-side. In addition there is a variation on the more common subsection system, with 6 rather than 8 marriage classes. People may be called and referred to by their ‘skin’ – in short, by their section name. Tj. Davies produced a memorable painting showing diagrammatically how the system works: ‘Right Way to Have a Kurri’, 1992, Warburton Art Collection #026(L).

Kurntili: Aunty (FZ) in the Ngaanyatjarra language; roughly the equivalent of Tia in Tetum.

Saddo: Sadleir, a suburb in the far south-west of Sydney, near Liverpool. In the inner suburbs Paddington is called Paddo, Darlinghurst Darlo … Not all suburbs have such contracted names but Parramatta is called Parra, Liverpool Livo… People too can be subject to the same process: a notable example is the ‘ocker’ entrepreneur and advertiser, John Singleton (‘Singo’), who promoted an aggressive larrikin style.

Imprint

| Artist | Albertina Viegas |

| Exhibition | La’o Lemorai. How to be at home in the absence of home |

| Place / venue | Municipal Gallery bwa Bydgoszcz, Poland |

| Dates | 11 December 2020 – 24 January 2021 |

| Website | www.galeriabwa.bydgoszcz.pl |

| Index | Albertina Viegas John von Sturmer Municipal Gallery bwa in Bydgoszcz |