Anna Mituś: When running the Master’s Studio in 2012 (then sub-titled Curator Libera), Zbigniew Libera told me, paraphrasing Tuwim, that he knew as much about curating as a bird knows about ornithology. How do you define your role in this project? What is the Mistress’s Studio like?

Joanna Rajkowska: Similar. I also have the impression that I am participating in a certain almost chemical process, a certain experiment on a living body. Someone speaks to me, I absorb it, insights flow in my head rapidly, like lightning… Then, before I forget everything, I spit it out like a medium spits out ectoplasm. And we keep moving forward like this. Some people benefit from it, others don’t. Seriously, I learnt to ectoplasm like this precisely when working with Naked Nerve.

The group of participants in this edition of the project is exceptionally big. More than 200 people responded to the call for a potential collaboration with you. I remember the evening on the third day of the interviews, when you narrowed the list down to about 25 names, and after that it was very difficult to further reduce this number. In hindsight, how did the criteria you used to shortlist the exhibition participants work out? Courage, nudity, the ability to take on the role of a medium for reality – did I miss anything?

I think I was also concerned with resonance. I’m very drawn to artists who react like this museum equipment that reacts to ground shaking. Or like a windbreak. It blows and the person gets inflated by this wind, fluttering.

The criteria worked well with those of our artists who were somehow crushed by reality. Or in the case of those artists whom we urged to pursue their original projects at all costs and did not allow them to play around with them endlessly. This is because contrivances and speculation aren’t good. I am especially happy about the level of the risk they took, when they did.

All right. Did they? I know you treat all individuals in the project as equal partners – what did you learn from them about yourself and your work?

There were both female and male partners. They did take risks, not all of them though. As for my work… Hmm… I guess I learnt that regardless of my admiration for many of them I cannot work any other way than I do. 🙂 Well, maybe also that I am a bit too heavy. And that I am detail-obsessed. I tried to be as gentle as possible in my relation with them, but I think they might have felt differently. I certainly don’t have a sexy laid-back attitude. Anyway, it’s hard to have sexy ease when you’re throwing others out of the window.

Who has thrown who out of the window?

I have the impression that I would sometimes throw them out of the window. In co-thinking, accompanying, standing by their side, I would advocate for a more radical choice. I would turn back when they wanted to make themselves comfortable in their creative rut. Sometimes, however, I had to let them go. They were already well-formed individuals, so I worked in their ranges, so to speak. The instruments had already been pre-tuned.

Tell us more about what you have been able to communicate through this exhibition.

I think I’m going to surprise you, because I got surprised myself when it occurred to me. Naked Nerve is the most anti-right-wing position (not: exhibition) that we have been able to define together. We don’t believe in boomers’ recipes, I guess this goes without saying. We didn’t adopt any boilerplate solutions. It was essential for me that no one should settle for pre-made concepts or languages. I wanted the artists to be vulnerable and yet attentive. It seems to me that the bios of our bodies (and of every body, human and otherwise) is the only sovereign territory. Vulnerability allows you to open up to other entities. Summing up, we told those who feel like using violence against these defenceless bodies of ours to fuck off.

Admittedly, I was also surprised by this change of language, to the ‘uncivil’ one. The use of strong language is a symbol and at the same time a performative act of rejecting the conventional language games that have failed us in the course of this year. I would like to talk about the second important issue that overshadowed the preparations for the exhibition. Covid is an expected consequence of anthropopressure, which drives us closer to even more serious problems. How did the context of the pandemic impact the shape of Naked Nerve?

I know it struck some artists, in various ways. I remained on the outside of the problem, it didn’t touch me at all. Nor did it touch the Naked Nerve in me – its concept or progress. It was common knowledge for a long time that there would be pandemics, we have been reading about them for many years. This is just the first of them. Many people we hold dear have died. I’m more disturbed by successive species going extinct than by a virus that we have generated ourselves.

Right. Let’s stick for a moment to this affect that triggers the most primal, somatic reflexes. In your conversations with artists, there were many moments when you invoked imagery that appealed more to personal corporeality than to some elaborate ideological or theoretical constructs. You wanted them to put trust in something that made them part of an experiential community of feeling. Do you think that this kind of art has more to say to us than erudite art that mediates relations between different fields of knowledge?

That I don’t know. I wasn’t talking about an experiential community of feeling. What I meant was the response we give to reality. As a single body. Any kind of response – from the air we breathe, to our response to the partners we have sex with, to social fabric we create, to political games we engage in. I am interested in this response, in what lies between us and reality. So I urged the artists to be within the body, in unity with the body, immersed in corporeality, while creating this response. What I mean is the materiality of the body, its temporal character, its imperfections. We are as ephemeral as fruit flies, but the body’s resonance with the world, albeit painful and bitter, produces powerful art. Besides, what you called erudite art is so fucking boring it makes you want to cry. And it doesn’t have any of the potential that comes with silliness, a blast, you know, the kind of kick that gets your head spinning.

Someone told me once that truly interesting art is hardly possible without the risk of failure. When inviting artists to collaborate on Naked Nerve, did you consider the risk level of their projects?

I did, sure. Failures must be an option. No risk, no art. I also hoped that no one would be crushed by them. Art schools should teach you to talk about failures, your failures. This requires distance from your own grandiosity, and a sense of humour. 🙂 Unfortunately, however, art has fallen into the trap of capital and increasingly reproduces marketing procedures. Marketing has manufactured the entire culture of façading reality with its ‘image’. I could talk about it for hours. Ageing, stratification of the culture of late capitalism, separation of reality from its epidermis, of language from meaning, this fatigue and overuse of theory, and the perpetual boredom, crisis, therapies, despondency. Risk aversion culture, in other words, demise. Risk becomes the only means to rescue us from this slow agony. Risk, body, matter.

One word that springs to mind is ‘east’. It’s a sort of an antithesis of the Enlightenment project, which has failed and exhausted everyone. Despite all the love I have for it – because I think we didn’t do our homework on the Enlightenment well, and Romanticism was likewise processed poorly here – I understand why you resent the late capitalism that resulted from all of this even though we had learnt our lesson quite well. Is it better to throw it all out of the window? What can we learn from the east?

Relationships, touch, warmth, energy, simply – life. I recently shared a train compartment with two Ukrainian boys. They were young, discreet, well-mannered (yes!), free of Polish roughness and Western indifference. I closed my eyes and tried to remember if I knew any similar Polish boys of that age. And I couldn’t.

For me, the East represents the possibility to think and shape relationships – or even the world – in a different way. Literalness (Eastern languages allow for much closer description of material reality) which is not primitive and which has the power of a real contact. All this is rooted in a slightly different understanding of reality, images, art and its functions. Icons never constituted luxurious entertainment, they didn’t represent, they didn’t create distance. Icons were a window to the intensity beyond our reach. They held power over people, rather than being objects to be analysed. One had to submit to them. Such an approach to total art that’s brimming with magic and power can save us from endless autotherapy of the West, which, according to my intuition, will no longer produce anything of much interest. I’ve been listening to Mark Fisher a lot lately, to the last lectures he did before his suicide. I was fixing my puppets, worn out by a film set, and literally the chisel fell out of my hands as Mark was talking about the decline of a sense of time, a sense of time in contemporary music. In the background, there was London – overcrowded, full of aggression and forced ‘sorrys’, averse to experimentation, lacking freshness. I always knew I had inherited a culture that may be more primitive, but one that is younger, fresher, twining like a stalk upwards. And it was there, in the UK, that I embraced it very consciously, drew unashamedly on the traditions of Eastern Europe, on our scars, spectres, hallucinations, Eastern European Hasidism, sick messianism. I felt the magnificence of it. I saw it from a distance. A fabulous chanting procession. Amazing potential, magic. There is so much to draw on.

Do you see that in our exhibition?

I do, but no one has taken the risk of leaving the territory set by the Enlightenment.

This seems to imply a failure of our project?

No, let’s not exaggerate. The objective was not to leave that territory, but to activate the body. A deconstruction of constructs down to their physical foundations. Holding the matter of the world in which we are living and this East-West cultural edge up to the light.

Seventeen projects is a lot, so let’s try to somehow structure the image that will reveal itself at the exhibition. Which of its features strike you as characteristic of the moment we are in? To my mind, many of them bizarrely mirror each other and create connections, so that certain themes are reinforced and form a pattern. Just to give you an example: Marianka Grabska’s work on orphanhood and the work by Kasia Hołdys, who hosted us in Kashubia, both deal with the subject of parenthood, and motherhood in particular. Both make pain the main critical tool. Both of them, due to their being rooted in crisis and borderline issues of motherhood, are responses that make us reflect on what we no longer find acceptable in the established vision of reality. The former starts with what is social (language) and follows the affect (pain) so it can manifest itself in the social context despite the inadequacy of the means. The latter, following an instinctive reflex, seeks justification for this reflex and finds it in a completely different scale of thinking. It is a new scale that transcends the horizon of our own species, which we are only just getting used to, although we have been receiving alarming signals for half a century. Am I right to think that this radical but also empathetic perspective, stemming from the female body, is one of such patterns?

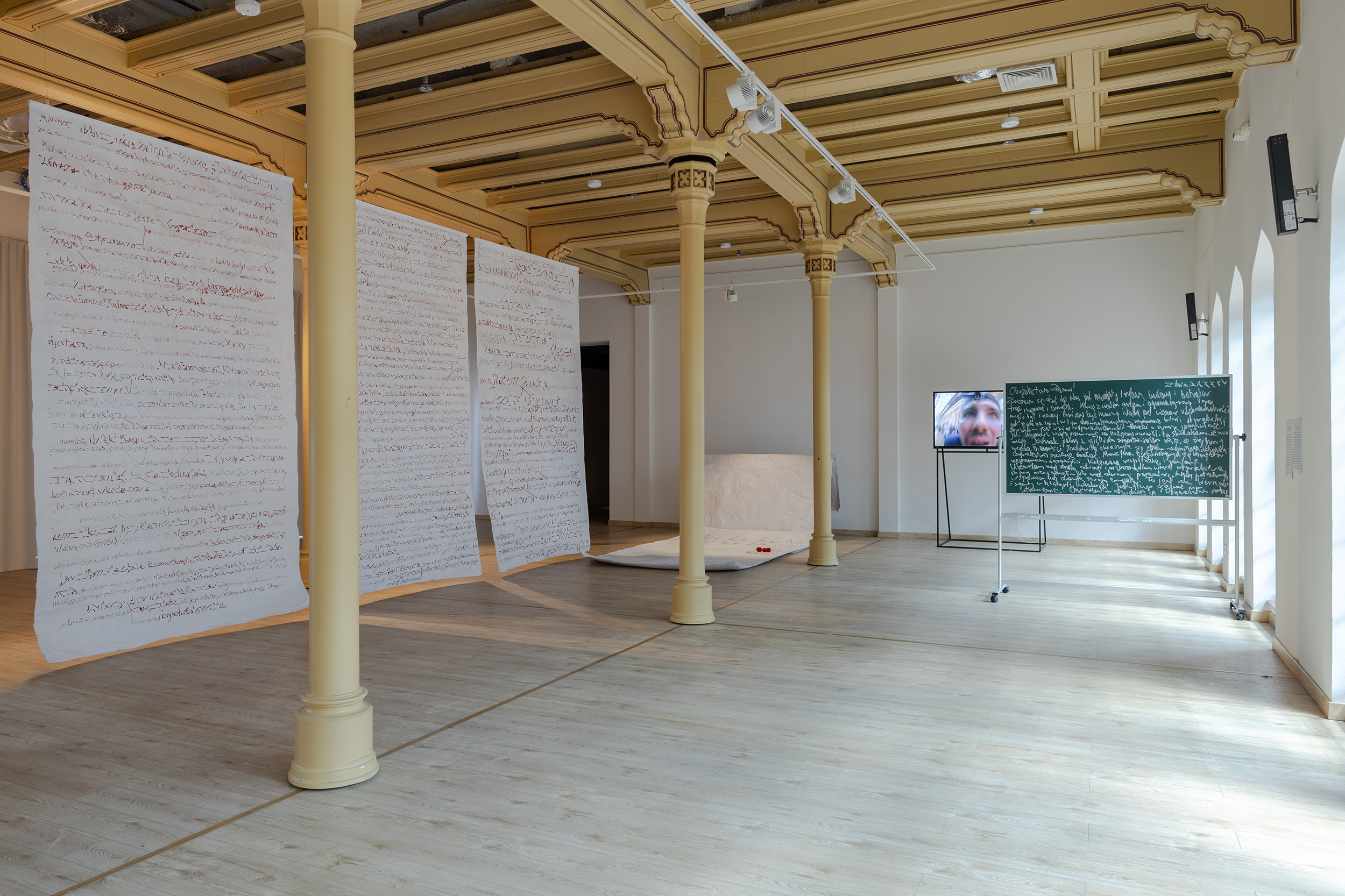

I think so. I am still in the phase of ‘throwing out’ these works, the arduous process of defining the process, the experience, finding and polishing the language. Marianka, Kasia, as well as Irmina Rusicka, Viktoriia Tofan and Paulina Pankiewicz performed an operation on an open body, taking what is inexpressible and totally painful, what comes from their bodies and what the body cannot experience, in an attempt to tame it and reincarnate it in some other matter. What I find very peculiar is that when language was concerned, it was transformed into non-linguistic matter, into a clatter, or distorted into runic embroidery. Motherhood, the unrecoverable loss of a child or a mother, physical limitations – being unable to see, speak or hear – all this sends us inside the body. In fact, it did automatically guide us inside other bodies, other entities. This happened in case of many artists in Naked Nerve. The initial impulse was indeed pain.

It will be similar in the performance by Daniel Kotowski, in which the body deconstructs the language and sends its own message, or the work by Kamila Kobierzyńska, the recording of which, a lullaby, we still only know from the description. However, I suppose that singing, by which pregnant women communicate with their yet unborn children, is a vibration of its own, autonomous, soothing value, regardless of the lullaby lyrics.

Yes, both Daniel and Kamila have turned language into body vibration. On top of that, while sticking to sound, they refrain from using articulation or modulation – what you actually hear in white singing is the work of the diaphragm, and Daniel uses his throat so that we could hear his speech apparatus, and not words. This absence of words, especially coming from the figure of a dictator played by Daniel, is very telling.

This is not the only peculiar transformation in the exhibition. Jakub Jakubowicz talks about the trauma of the Lemko community, the human trauma, by means of ozokerite, an earth wax, and Dominika Macocha turns an old, presumably burnt down Jewish inn into a book. We’re on the threshold of alchemy here. 🙂

So we have the alchemical nigredo, as well as chemical and biological transformations. We are taking things to a certain common level…

There are many works depicting our culture in terms of life processes of other organisms or juxtaposing homo sapiens with other species, or even with the matter of other entities and products of technology. Mateusz Kowalczyk works with hemp, a fantastic but terribly stigmatised plant, Katka Blajchert juxtaposes natural and synthetic hair with flax thread, and Agata Siniarska in her work Still Life juxtaposes animal skin and fur with her own skin by means of movement and body gestures. Social rituals, dressing up, wearing others’ bodies on our own bodies are not so much criticised here as reduced to material basics. This thinking process in the medium of matter, closeness to life processes, and literalness is what creates a relationship with the world from scratch. With its matter, and not its cultural or commercial imagery.

I have the impression that our artists employ matter to dissect what might seem to be completely abstract notions, such as nation, language, history?

Yes, we very rarely deal with constructs, and if we do, as in the case of Viktoriia, with language, then it is arduously converted with a needle into the form of a hand movement and a pattern of embroidery, converted into runes, which, on top of that, are seen from below. Deconstruction of the language matter is also almost physically tangible in Przemek Piniak’s quasi-speech constructs. Both his work and that of Ala Savashevich involve a play with a specific moment of tension, of this situational tension. Using speech, Piniak seizes an indescribable space, weaves a web with these articulations like a spider, picking on meanings, or rather their remnants. In turn, Ala works with a space left after an overthrown monument of a dictator. His gigantic decapitated head is a head that has just come off a body, gone soft, lost its form. Implicitly, however, this is the moment all of us always wait for: when the planet’s gravity, at last, after much anticipation, knocks the monster off the pedestal.

I really like this moment of degradation, which captures the freedom to do something, the freedom to make a new beginning. A bit like in Patti Smith’s dream about the death of Alfred Wegener. It’s a vision that she had while burning souvenirs from the Continental Drifting Club. Let me quote her elevated conclusion: ‘These are modern times, but we are not trapped in them. We can go where we like’. There is some kind of joy in every ending. The exhibition features several works about borders and crossing them, such as Border Plough by Magda Romanowska.

Border Plough may be the most mysterious work in the exhibition. Its job is to plunge its shares into the soil to mark borders rather than to plough. Here, the land is the ultimate point of our human reference, something that, despite desperate human efforts, determines our existence. And it literally marks the borders of a life-giving (rather than abstract) territory. The limits are also explored, to varying degrees of emotional distance, in the works by Irmina Rusicka and Kasper Lecnim. Grave for Mum, with water feeding millions of living forms, is essentially a drinking pond. In turn, Kasper Lecnim’s world after the end of the world serves merely as a background for non-reproductive, exuberant sexuality.

Our conversation comes to an end here, the rest is the exhibition. All the works are getting last-minute finishing touches, so there may be many surprises in store for us, but that’s the risk you were talking about earlier. The set-up is already underway, and it’s animated since several artworks are being constructed on site. I have decided that the exhibition itself will be kept naked, bare, not wrapped up in a design thinking. Thus, this time there is no set designer or specially produced exhibition elements apart from the scenographic module of the Bureau of Worthwhile Activities, which was developed in collaboration with Wrocław University of Technology and made of milled waste paper collected by cultural institutions, and which sets a certain course that we follow together with Maciek Lizak, the exhibition’s graphic designer. The inclusion of certain features, such as dividing the exhibition space with low, technical platforms is dictated by the need to mark out a safe space for visitors with visual impairments. Together with Pamela Bożek and Paweł Błęcki we are also planning to gradually expand the structure of visitor’s paths, first by diagnosing, and then by implementing solutions to increase the show’s accessibility for people with special needs. In the course of its three-month duration, the exhibition will also be accompanied by a commentary on environment-related issues, prepared in collaboration with the FER Foundation for Sustainable Development.

Imprint

| Artist | Katka Blajchert, Paweł Błęcki, Pamela Bożek, Marianka Grabska, Katarzyna Hołdys, Jakub Jakubowicz, Kamila Kobierzyńska, Daniel Kotowski, Mateusz Kowalczyk, Kasper Lecnim, Paulina Pankiewicz, Dominika Macocha, Przemek Piniak, Magdalena Romanowska, Irmina Rusicka, Ala Savashevich, Agata Siniarska, Viktoriia Tofan |

| Exhibition | Naked Nerve |

| Place / venue | BWA Wrocław Główny, Wrocław, Poland |

| Dates | 28 May – 12 September 2021 |

| Curated by | Joanna Rajkowska |

| Photos | Alicja Kielan |

| Website | bwa.wroc.pl/ |

| Index | Agata Siniarska Ala Savashevich Anna Mituś BWA Wrocław BWA Wrocław Główny Daniel Kotowski Dominika Macocha Irmina Rusicka Jakub Jakubowicz Joanna Rajkowska Kamila Kobierzyńska Kasper Lecnim Katarzyna Hołdys Katka Blajchert Magdalena Romanowska Marianka Grabska Mateusz Kowalczyk Pamela Bożek Paulina Pankiewicz Paweł Błęcki Przemek Piniak Viktoriia Tofan |