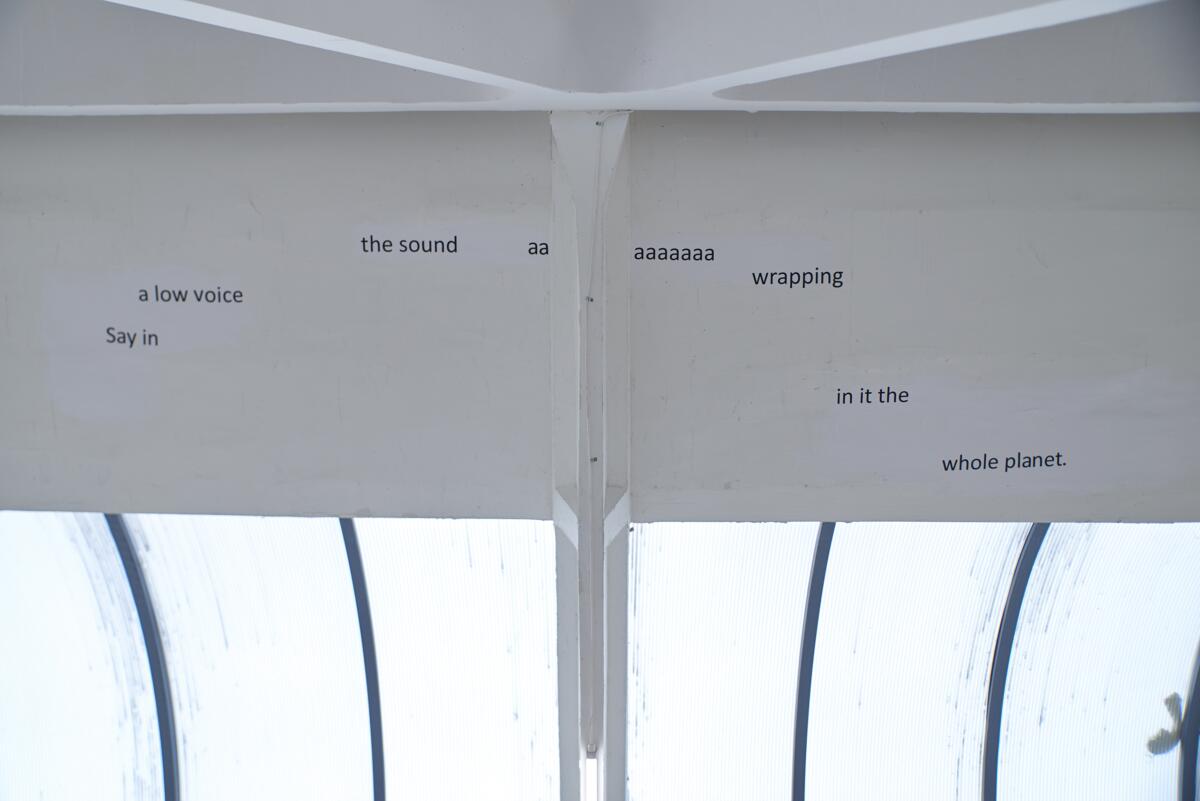

The last time I had the chance to visit Kunsthalle Bega, its entrance was in the middle of a construction site one had to cross to enter. Now accessing it from the other side, the hints of how such a space is sustained, through a shared location with some shops and a gym, are hidden from sight. Yet, the metal grid staircase you climb to enter, and the architecture revealing the support beams throughout the exhibition space, enable you to perceive another space, revealing its difference to a typical art museum, but also becoming an emblem of the entanglement with capital. With the latest exhibition, curator Anca Verona Mihuleț decided to show the hall as-is, leaving free spaces between the artworks as if to point to her awareness of the support structures rather than hiding them. Walking through the exhibition, it becomes clear, though, that there are no gaps. The perceived emptiness offers space for actions taking place during the exhibition. Adriana Chiruta’s installation, which stretches throughout Kunsthalle Bega’s exhibition hall with text fragments on the floor and walls, is the only kind of element that can survive in this space of minimalist architecture. The poetic approach might turn every reaction to it into art, becoming the most subtle work of the exhibition. Another reason for these free spaces is the proposition by Stardust Architects, who invited contributions by several architecture collectives that turned to other fields of practice. In an aesthetically pleasing display on a round table in the middle of the exhibition space, with a focus on the “recovery” of crafts and skills such as recultivating old varieties of vegetables, thinking about new construction materials on the basis of hemp, natural dyeing methods, and so on, the invited projects stand for a current shift toward revitalizing materials and practices. This is backed up with workshops by the architects, and extended by the educational programming of Kunsthalle Bega with additional offers for different age groups.

This smoothly aligns with the idea of the exhibition title: Chronicles of the Future Superheroes, which is an adaptation of the recent children’s book’s Danielle: Chronicles of a Superheroine by US inventor Ray Kurzweil. In the book, a young girl is, for example, using slingshot machines to purify water, battling a drought in Zambia or becoming “chairgirl” of the Chinese Communist party and re-arranging the state apparatus. While the good intentions in the story are clear, a strange aftertaste remains: A young, intellectually gifted girl, raised in a family supporting her plans ideologically and financially, and giving her access to great education, manages to solve major global problems with ease. In its straightforward narration the book seems more like a contrast to the artworks Mihuleț brought into this exhibition. It seems to talk about what would be possible with privilege and does this from the stance of a straight male US transhumanist. Even though the story is about a young girl and addresses issues of gender equality and racism, it speaks from an obvious perspective embracing normative and neoliberal structures, and even more meritocracy. This oversimplified account of how to obtain global freedom and equal rights makes it paternalistic. In Danielle, it is clear what a brighter future might be and that by doing certain good things this will come about – and that we always know what that right thing to do is. But only the architects’ propositions for the exhibition entertain such a precise vision. And even their practices remain in a speculative realm of trying out and remaining small in scale, far from becoming the sort of impulsive agency in Kurzweil’s entrepreneurial sense of creating a solution to a single problem. Works in the exhibition directly responding to future concerns such as climate change rather helplessly amplify the current urge to act, as the neon signs by Dimitar Solakov metaphorically transform the words “permafrost” and “icecaps” into dysfunctional announcements, as half of the word flickers as if it’s about to stop working.

The privilege and lack, in both relations and empathy, to the surrounding world and the people of the book seem to point to the opposite of what the exhibition does: it presupposes that you have to act with massive impact rather than to first understand the situation. All the works of the exhibition instead have a very clear understanding of their environment. They are conceived out of a precise understanding of where they are situated and react to that cosmos. There is no such global hubris to make the entire world a ‘better’ place to be found in the exhibition. It is actually good that none of the art projects lose themselves in a claim like the one Kurzweil entertains. While the beauty of all the artworks is that they point to some possibility of a different reading of the contemporary t issues currently at stake, the utopian impulse of the title is misleading. It really isn’t the future that they are dealing with, but rather the present.

This is apparent already in the huge installation one encounters when entering the space. It is a radar-shaped wooden structure made from smashed car windshields from the region around Timișoara, conceived by artist Baptiste Debombourg. The history of these accidents creates a connection to the fragility of humans on earth, their short-lived possibility of existence, which is in danger if it cannot save itself from threats – and thereby emphasizing the need for these Danielle-like heroines, not that they could or should take over and will solve all problems.

Despite such approaches to push the boundaries of the connotations of the exhibition title, with some pieces in the exhibition, the question of their contribution to its narrative remains open. Beautifully interweaving different images, for example, the works by Croatian artist Dalibor Martinis questions a certain linear notion of time, commonly known as our clock time which successively orders events and structures, lives and work. The three videos played are a double exposure of the same cable car route traveling in both directions, videos of New York from 1984 and 2001, and the film of an installation where the artist’s DNA is translated into binary code which becomes the pattern for swinging chandeliers, all of which is set to an aria sung by his aunt. While the implication of the work is questioning linearity, the radicality of this proposition is lost as it is only using the difference between two distinct past events to create that effect.

One could situate Heecheon Kim’s film Deep in the Forking Tanks as a counter movement. While the points of departure, the narration of a sensory deprivation tank and the story of a friend who disappeared in the ocean, already creates an uncomfortable feeling, the everyday scenes add up to this as they seem like randomly recorded conversations and meetings, maybe related to these events. Yet following the conversations, we find one strand telling us about a group of young people in Mexico imitating K-pop style dances in front of shop windows on their so-called “Day of Automation”. The artist compares it to driving automation, where the way is based on algorithmic prediction thereby folding the future into the moment the destination is set. The same happens in the choreographies, thereby letting the dancers leave their bodies in a sense. Heecheon Kim furthermore seamlessly weaves face swap filters or CGI into the narration, almost unnoticeable as they are sometimes pixelated or in the style of a camcorder video, thereby connecting his real body to the virtual one, and blurring our perceptions between ‘reality’ and technological images. The ordinary conversations, the idea of a lost friend, the dance, and the sensory deprivation tank then all become blurred to the point of detachment from past, present, and future events – as all parts of the narrative emphasize the distance to your body.

A different kind of estrangement from the body is in Adina Mocanu’s work which uses the story of the Russian mentalist Nina Kulagina. She was famous even beyond the borders of the USSR for her abilities of telekinesis. Mocanu refers to this story in the videos presented in her installation. The mode of presentation creates two ways of reading: The stunning stage made of broken pieces of stone plates and a variety of old screens pushes the narration in an obscure past, not only the historical past of Nina but also media of the 80s, 90s, and early 2000s where such stories were sensations on public TV. The other aspect is a performance in which the artist narrates a story in which Nina is actually not dead. She is in charge of her telepresence on the internet, showing her powers and trying to lead people away from their lack of belief in imagination. The work becomes a powerful statement for new imaginaries and the belief in more-than-human powers as she states that only Soviet officials attached strings to the objects to trick others into questioning her powers. At the same time, though, tied together with her utterance that the social construct she grew up in led to a lack of trust in her body’s powers, the interpretation remains open: rather get rid of the strings or believe more in absurd stories on the internet?

Maria Pop Timaru, In God We Trust / Saviour/ Who will save us from ourselves?/ SOS /Looking for a hero/ Where are You?, Sculpture, glazed ceramic, polystyrene, cement, wood, plastic, led tube, led strip, silicone, 113 x 120 x 230 cm, 2021 | Exhibition view at Kunsthalle Bega. Courtesy of the artist and Kunsthalle Bega | photo: Vlad Cîndea

Maria Pop Timaru’s sculptural being is addressing another possible superpower. The work shows aspects of how the artist imagines its manifestation: a combination of ancient cultures, as shown in the shape of the base, and some features of an insect’s head, at the same time colorful but blending into the exhibition space with most of its ‘body’. While we can worship this alienating appearance, it eventually brings us back to the (im-)possibility of transcending our world while we desperately want to. The feeling of a sensory deprivation tank of political, societal, and ecological consciousness. The exhibition is ambivalent in its use of the magic emanating from the artworks. The references to the void and the impossible, as well as to a reading which renders this possible, are all there. Then again, the architecture and the title force other readings. It seems, the reference of the exhibition to the tech big shot Kurzweil is summoning all the supposedly ‘bad’ things we want to avoid noticing in the art world: the connection to industries and companies, finances, etc. – the entanglement of ideas of progress with a philosophy of entrepreneurial growth and capitalism. Yet, we have to deal with all these things. And we cannot avoid change or the future or whatever you may call it. Despite their beautiful appearance, in the framework of this exhibition a similar feeling of doom accompanies the works by Fabio Lattanzi Antinori, Dataflags and Masters and Slaves. Google, where they sing trading data from Lehman Brothers while touching a silkscreen print, or visualizing the flash crash that hit Google in 2013 with LED chains. But maybe there’s a spell against the conjuring of Danielle’s neoliberal agenda that seems to force us to use entrepreneurial strategies to make the world, ruined by the very same strategies, better. Lawrence Lek’s film AIDOL, for example, inverts the common-sense narrative of the rise of machines against humanity, showing the appreciation of an AI artist for values such as beauty and being touched emotionally, extending his Sinofuturist universe that is rooted both in the fascination for East Asian technological success and the fear of it. This provides a more nuanced view in opposition to Kurzweil’s attempt at saving and adapting ‘them’, while simultaneously refuting the economic position of China and where this interest originates, all the other works of the exhibition have similar roots in reality which they embody, as stated above.

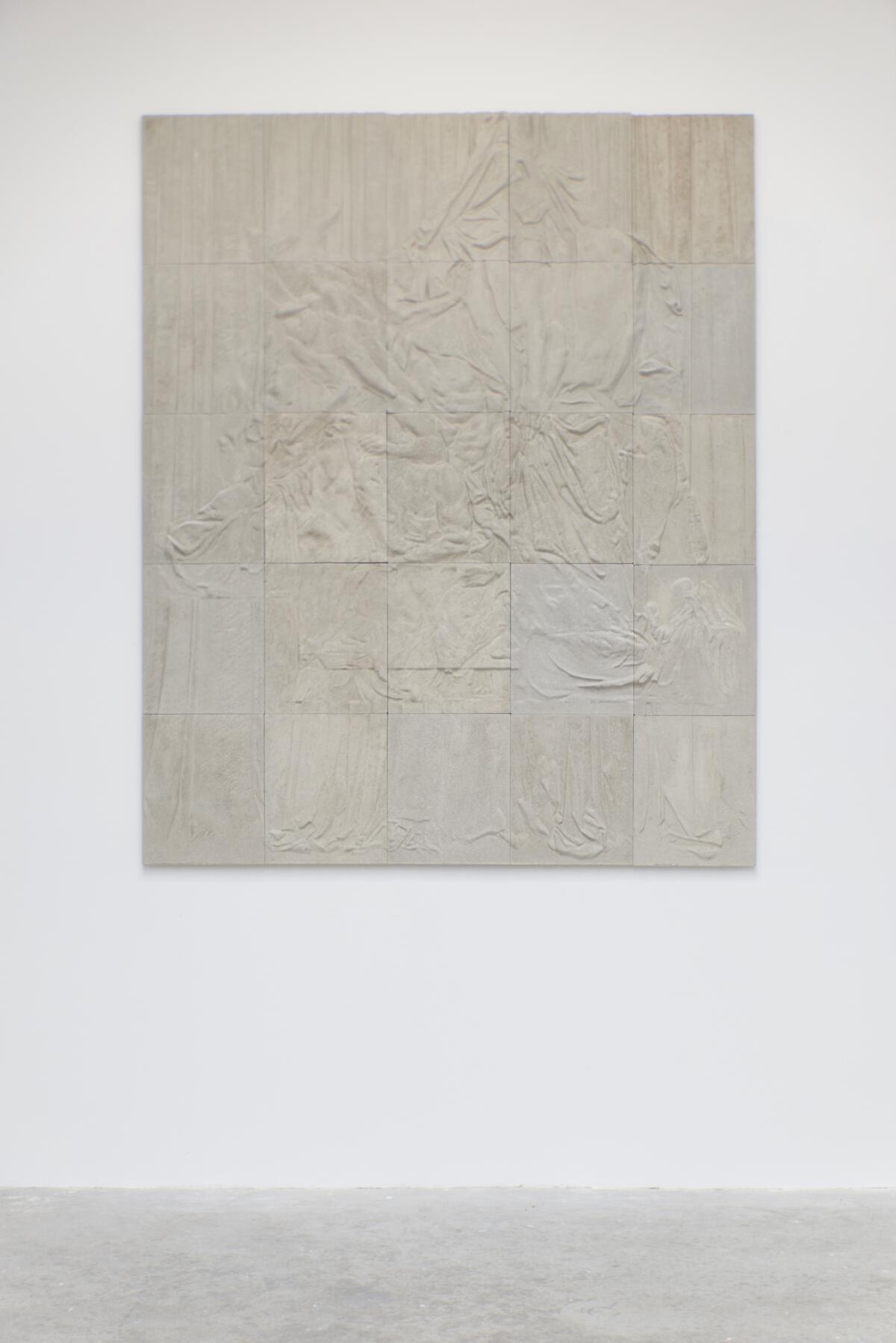

The strength of Anca Verona Mihuleț’s curatorial work is actually not to follow the idea that this book presents to us. She doesn’t impose the superheroine status on any of the artworks, and none of them really aims for it. This exhibition is beautifully personal despite its ‘clean’ appearance in the space of Kunsthalle Bega. This two-faced experience, though, is only enabled by the artworks which made me constantly question the perspective of the book by Kurzweil. The future superheroes are thus not the ones who are merely reacting to problems and spitting their solutions onto others. They are rather in the state of rehearsal, not knowing what is about to come. Quite like Hyunjin Bek’s strange installation in Chronicles of the Future Superheroes, said to be a Korean restaurant. In the description we learn that local material is used to create the characteristics of his country of origin, but much more it seems to be about modesty, what is possible to do from a specific point of departure, with all the big ideas in mind. Or like Larisa Sitar’s Study (II) for Aeternum, which deals with fantasies of immortality and eternal youth, nowadays often placed in the sphere of technological progress. Reviving the bas-relief as a genre for working on these ideas inscribes them into a history of power and representation, at the same time by only showing vague shapes, where only glimpses of human parts appear, disturbs the idea of showing the ideal. Refraining from the use of color shifts the work into a past: it seems the big ideas, even those about saving humanity, are of some past. The exhibition points to future superheroes having to find their ways, which are not visible yet.

Imprint

| Artist | Hyunjin Bek, Adriana Chiruta, Baptiste Debombourg, Heecheon Kim, Fabio Lattanzi Antinori, Lawrence Lek, Dalibor Martinis, Adina Mocanu, Maria Pop Timaru, Larisa Sitar, Dimitar Solakov, Stardust Architects |

| Exhibition | Chronicles of the Future Superheroes |

| Place / venue | Kunsthalle Bega, Timișoara |

| Dates | Timișoara |

| Curated by | Anca Verona Mihuleț |

| Photos | Vlad Cîndea |

| Website | kunsthallebega.ro/en/ |

| Index | Adina Mocanu Adriana Chiruta Anca Verona Mihuleț Baptiste Debombourg Dalibor Martinis Dimitar Solakov Fabio Lattanzi Antinori Heecheon Kim Hyunjin Bek Larisa Sitar Lawrence Lek Maria Pop Timaru Maximilian Lehner Stardust Architects |