Poles demonstrating against the tightening of the abortion laws have already managed to create a unique visual sphere of their protests. Historic monuments bearing graffiti with slogans and graphic symbols have become a platform for protesters’ statements. Where does this come from and what is the meaning of such contestation of symbols associated with the current ruling class?

Since October 2020 a wave of protests spilled across Poland, sparked by a decision of the Constitutional Court that tightened abortion regulations. On 22 October 2020, the Court ruled that the provision of the so-called ‘anti-abortion law’, which allows pregnancy termination in the case of serious defects or lethal congenital anomalies of the foetus, is unconstitutional. The provision will expire upon the publication of the ruling in the Journal of Laws but this has not been announced yet.

Due to protesters’ perseverance, these demonstrations – already labelled as ‘the largest in Poland since the political transformation in 1989’ – have been organised in various forms, several times a week in most Polish cities and many smaller towns. Additionally, in the past weeks, Polish public debate has been heated up by the still unresolved and constantly taboo subject of the large-scale cover-up of paedophilia by Polish church hierarchs. Pope John Paul II is also in the spotlight, despite his figure being the subject of unquestionable worship for the Polish church and conservative circles, and his impeccability being tantamount to maintaining the authority of the Polish Church for many years. This is reflected in the numerous statues of the Pope, located in every town and city in Poland.

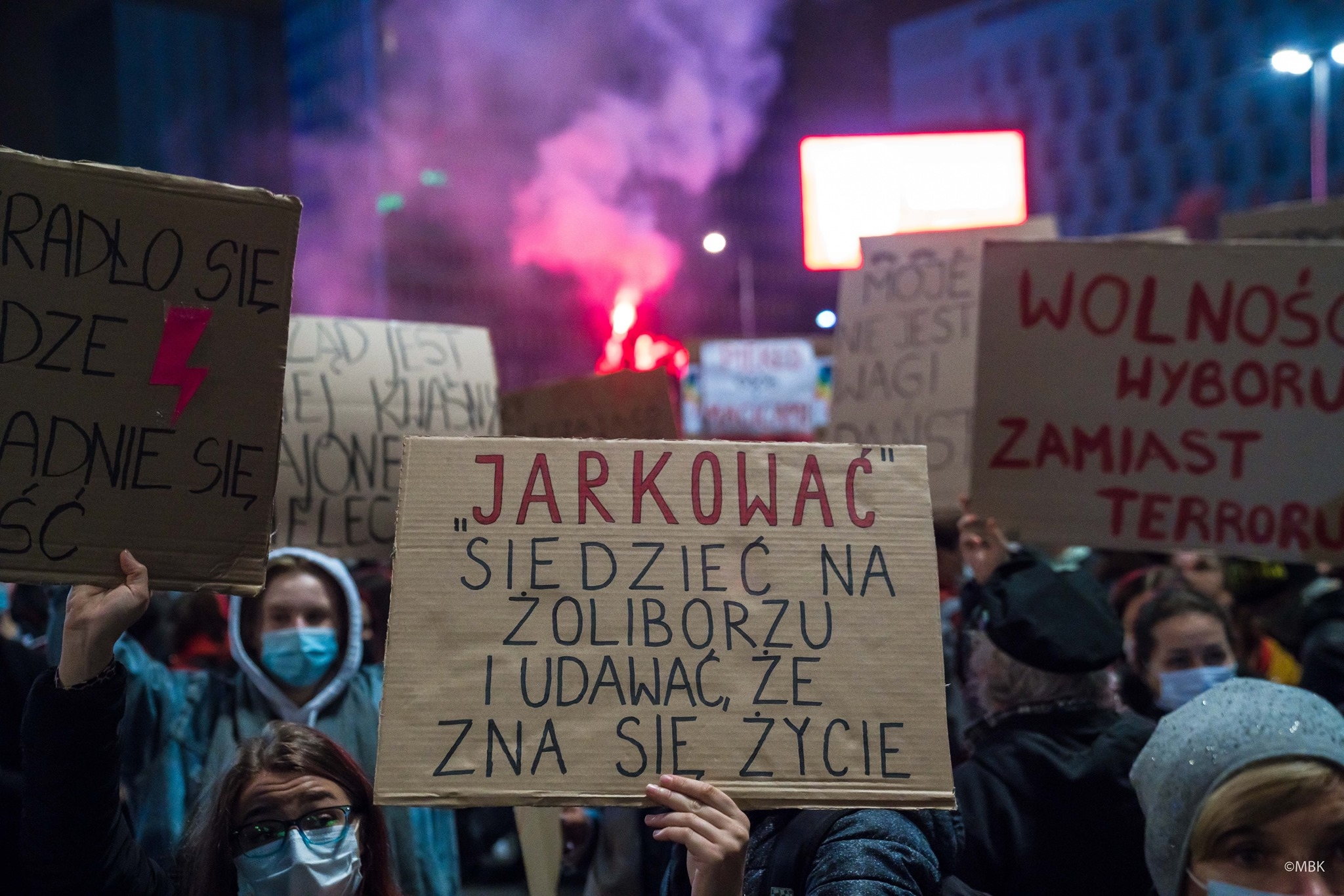

31.10.2020: protests in Warsaw, photo: Marta Bogdanowicz (Fb Spacerowiczka)

Over the past two months, during protests against the Constitutional Court’s ruling, spray paint has appeared on churches and such public monuments as the Testimony of Love on the Papal Hill in Luboń, the Monument of the 15th Regiment of Poznań Uhlans in Poznań, the Ronald Reagan Statue in front of the US Embassy in Warsaw, and above all on the above-mentioned John Paul II statues throughout Poland (e.g. in Poznań, Konstancin Jeziorna, Legionowo). The monuments were smeared with slogans directed at conservative politicians and the Church. Some of the graffiti included telephone numbers of organisations helping carry out abortion, which will become practically banned in Poland upon publication of the ruling. Images present in the public spaces became targets of protesters’ anger. Associated with the authorities, monuments themselves became a symbolic reference to the regime imposed by the ruling Law and Justice (PiS) party and to the influence of the Catholic Church on the private decisions of Polish women.

This is also the first protest in Poland’s history to make such a strong presence in social media. Interestingly enough, the most popular method for tracking reports on the strikes have been such platforms as Instagram and… Tik Tok, which have so far been used rather to share and watch short funny videos or photos of influencers. However, starting from late October, Instagram in particular has been full of reports from the protests. It has been used to monitor where the protesters are and where they are heading; short videos have also documented violent incidents involving the police. Notably, the above-mentioned influencers and celebrities have also played their part by posting messages of support for the protesters on social media, which in turn encouraged teenagers to join the strikes. Adolescents constitute the age group which, for the most part, receives information from social media rather than TV.

It is also the ‘mediagenic’ nature of the protests – which are largely present in the social media space, outside the circulation of TV news – that has influenced the strikers to create their peculiar visual realm. It comprises slogans and symbols sprayed on historical monuments as well as those placed on cardboard protest signs that are so often photographed by journalists and later published in all media channels.

31.10.2020: protests in Warsaw, photo: Marta Bogdanowicz (Fb Spacerowiczka)

The most popular visual symbol has been a red lightning bolt placed on monuments or profile pictures of people supporting the strike. The symbol originates from the logo of ‘Polish Women’s Strike’, a social organisation responsible for organising protests all over the country. As the creator of the logo Aleksandra Jasionowska says, the lightning bolt was designed as a warning symbol – universal and understandable to everyone. However, pro-government media criticizing protesters compared the lightning bolt to Nazi SS imagery. This made it easier for them to condemn the protesters and compare them to fascist militias, which in turn triggered a storm of online comments.

A slogan reading ‘get the fuck out’ has become emblematic of the protests. It has often been accompanied by such slogans as ‘this is war’ or ‘I think – I feel – I decide’. Another significant symbol frequently appearing on protest signs as well as online (for at least half a year now) have been eight stars, which is a censored version of the slogan ‘F*ck PiS’. From the very beginning, catchphrases with tragicomic potential can be seen on the banners too (e.g. ‘I’ll give birth to a lefty anyway’ or ‘Girls just want to have fun(damental) human rights’), later going viral on social media. As Maria Poprzęcka noted a few weeks ago in dwutygodnik online magazine, those cardboard protest signs have become authentic expressions of spontaneity, ‘lower-ranking objects’ reclaimed from garbage cans or shop shelves serving as links between protesters and passers-by or audiences in front of the screens. The author also stated that they have become a reflection of the popular expression ‘cardboard state’ used with reference to Poland in recent years.

23.10.2020: activists protest near Jerzy Kalina’s sculpture of John Paul 2 in front of The National Museum in Warsaw, photo: Krzysztof Gonciarz

The online popularity of cardboard sign messages also shows that using slogans straight out of memes (so characteristic of today’s Internet users, mainly young ones) is becoming a strategy of resistance that can be used during mass demonstrations in public spaces. Applying Mitchell’s question ‘What do pictures want?’ to the protest signs, one could say that they have a potential to circulate and be reproduced, not only in the public realm – between protesters and passers-by – but above all they are capable of capturing the online realm. After each ‘walk’ (which is how organisers call the protests during the pandemic), when the cardboard returns to the garbage can, the slogans gain a second life in the media realm.

The same applies to statues. Although slogans and symbols quickly disappear from historic monuments, giving in to pressure washers, they remain anchored in the social media space. They build a symbolic visual space related to the protests and their representations.

However, it must not be forgotten that this visual realm was created for a specific purpose, as the cry of people who feel unheard and dismissed by decision-makers. Therefore, the goal is to ensure visibility of the protesters, while the statues and cardboards are only a medium for conveying messages and symbols addressed to passers-by and social media users.

All in all, this media potential contained in the public symbols associated with power should not come as a surprise. In recent years, representatives of the Polish ruling party have repeatedly selected new statue designs likely to inspire viral memes, which have also been seen in recent months. One of such examples is the Poisoned Well by Jerzy Kalina, installed in the courtyard of the National Museum in Warsaw. This artist, supporter of the ruling party, created a sculpture depicting John Paul II lifting a rock. This artwork directly referred to the 1999 La nona ora sculpture by Maurizio Cattelan. The work of the Italian artist, depicting the Pope crushed by a rock, sparked quite a scandal among conservative politicians, and the image itself has become embedded in Polish visual culture. Kalina’s memetic sculpture is compensation to John Paul II for the ‘desecration’ of the saint’s image by the foreign sculptor, at the same time embodying complexes of the ruling class.

Interestingly, in the new circumstances created by the protests, the realm of monuments – appropriated by the Polish authorities in the past years – has become a platform for statements by people who have been demonised and mute for several years. As if a discussion on the role and importance of ‘uncomfortable’ statues was stimulated from a completely unexpected angle. Yet, in the country on the Vistula, the debate has a unique character.

Police protecting monument dedicated to the casualties of the 2010 plane crash in Smoleńsk, photo: Alicja Defratyka

As Łukasz Zaremba writes in his book Images taking to the streets. Disputes in Polish visual culture, ‘after 1989 there was no clear iconoclasm removing the remains of communism. The situation spread out over time, and eventually was changed by the Law and Justice party [ruling since 2015 – author’s note], which erased a vast number of visual remnants of communism. In the meantime, church squares became full of statues of the Polish Pope and plaques commemorating the Smolensk disaster [Polish Tu-154 plane crash in Smolensk in 2010 – author’s note] as well as images of Lech Kaczyński [Jarosław Kaczyński’s brother, then president who died in the 2010 crash]’. It is therefore not surprising that protesters vent their emotions on these new creations in public spaces that accompany the ideological direction of the ruling class[1]. Zaremba looks for an answer to the growing number of emerging statues related to the government’s ideological direction of the government in ‘critical iconophilia’ creating new images, and in opposition to the authorities’ right-wing impetus (which, in the author’s opinion, does not mean that these newly created monuments should be toppled). At the moment, the protesting Poles are using both these solutions.

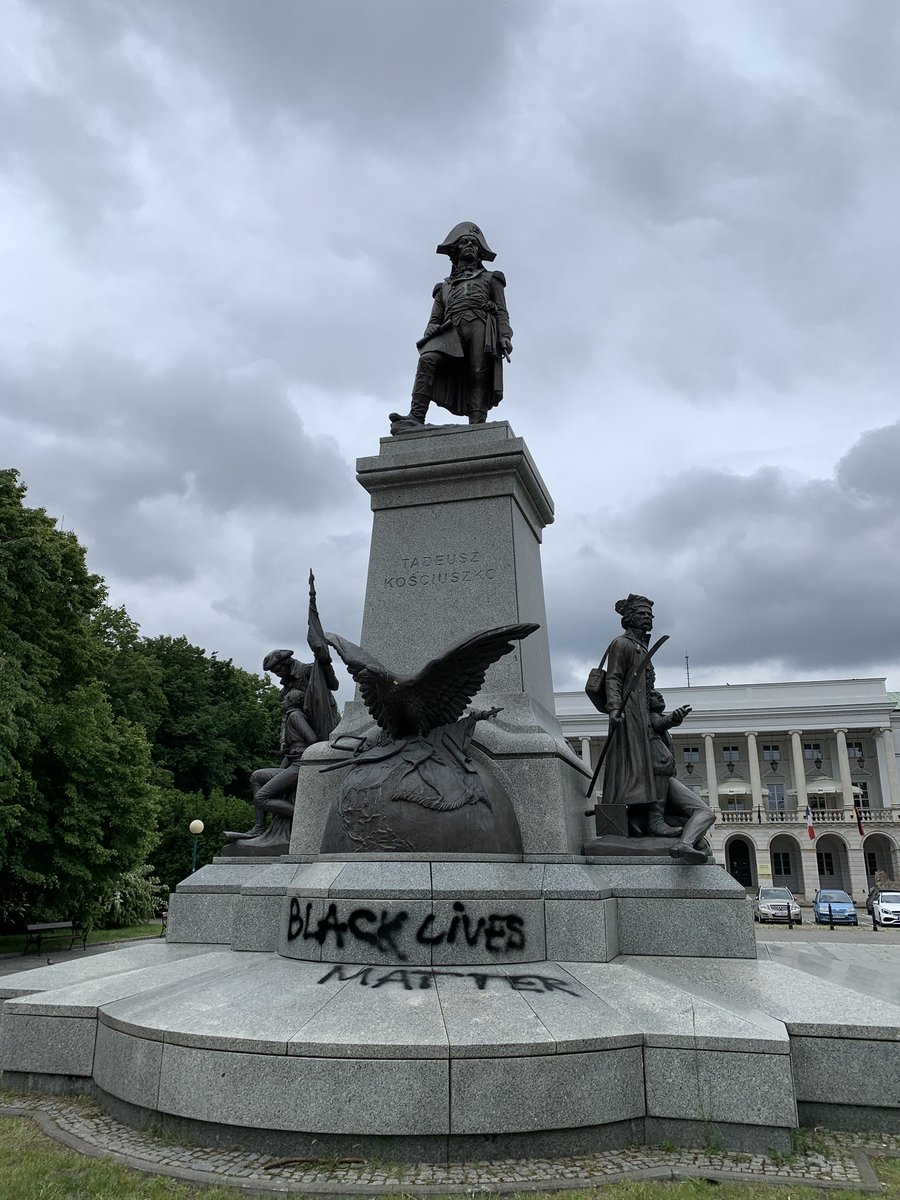

In July 2020, Karol Sienkiewicz wrote in dwutygodnik that the intervention on the statue of Tadeusz Kościuszko in Warsaw (where the inscription ‘Black lives matter’ appeared, in the author’s opinion referring to the values honoured by the General of the Continental Army) or last year’s 11th edition of the Warsaw Under Construction Festival entitled ‘Monumentomania’ (attempting to find a critical alternative to the growing number of nationalist and martyrological monuments being erected in Poland), only served as preparations for actions proper. Sienkiewicz suggests that statues should be used rather than remain dead.

It is worth adding that Sienkiewicz did not have to wait long for a response. A few weeks later, following a wave of hatred against the LGBTQ+ community (initiated by the ruling party that denies LGBTQ+ citizens their subjectivity, comparing people to the Bolshevik ideology (sic!)), urban activists began to use various monuments, placing rainbow flags in the hands of historical figures. The most symbolic and most frequently shared photos have been those depicting the Mermaid of Warsaw – the patron and guardian of the city.

03.07.2020: intervention on the monument to Tadeusz Kościuszko in Warsaw, photo: Dawid Styś

Critical responses expected by Zaręba and Sienkiewicz have been voiced in public for some time now, accompanying the protests against the growing tide of government hatred directed at citizens. This social contestation is manifested through media-oriented activities, dissemination of symbols and alternative visuality, which plays an extraordinary role in times when the media sphere is dominated by images. Protests for women’s right to abortion create a whole spectrum of visibility in the form of symbols, images and representations. They make a stronger impact on the consciousness of young people than most of the nearly transparent, often uncomfortable statues present in today’s cities. Unfortunately, we still have to wait a long time for lasting symbols of community to appear in our public spaces.

[1] On 13 December 2020, the authorities – alarmed by protesters’ actions – ordered a police cordon to surround the Monument to the Victims of the Smolensk Tragedy of 2010 and the Lech Kaczyński Statue in Warsaw, to prevent possible vandalism. They clearly understood how important the struggle for visibility has become.

Imprint

| Index | Stanisław Małecki |