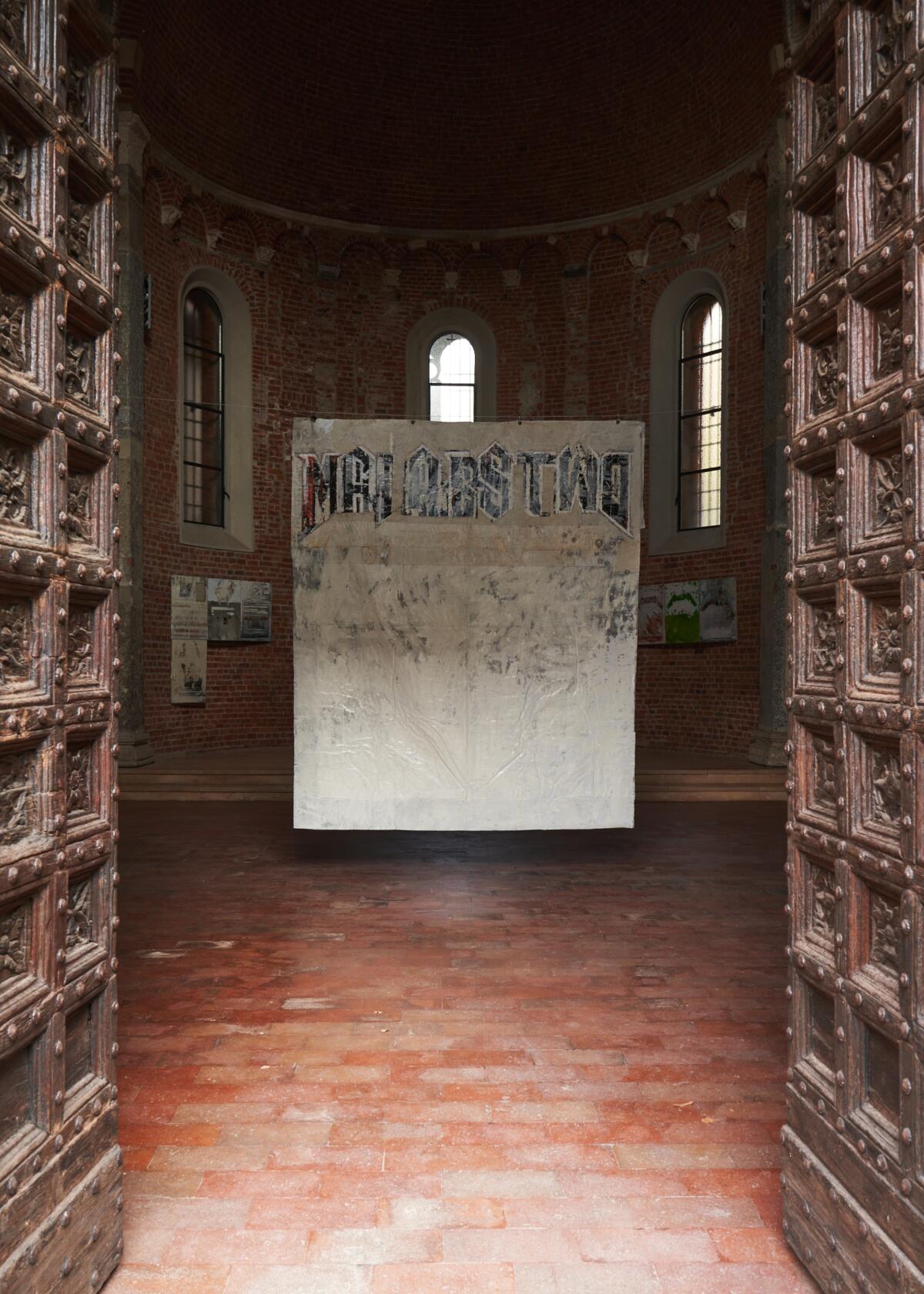

Dobrosława Nowak: Before we get into your work, I would like to talk about the space where your latest Milanese exhibition, Kill Your Idols, is held. Your work is already tremendously rich in references, but here, it is exposed in the consecrated basilica, now used as a space dedicated to artistic and cultural events. It’s a powerful curatorial choice.

Radek Szlaga: Yes, and it comes with consequences too. I was struck by the beauty of this place, just as a venue. The architecture is obviously spectacular. And the context…well, I didn’t really give it a thought. Kill Your Idols is rather a shameless ego trip. But I guess I found exhibiting in this location slightly perverse, especially when you take my older, more figurative works from the Iconoclasm series. The exhibition also refers to me turning forty-four soon; for us Slavs it’s a meaningful number.

I haven’t thought about it before, that’s very interesting. But let’s start with the question of the space you chose for the exhibition. We will get to the core idea later!

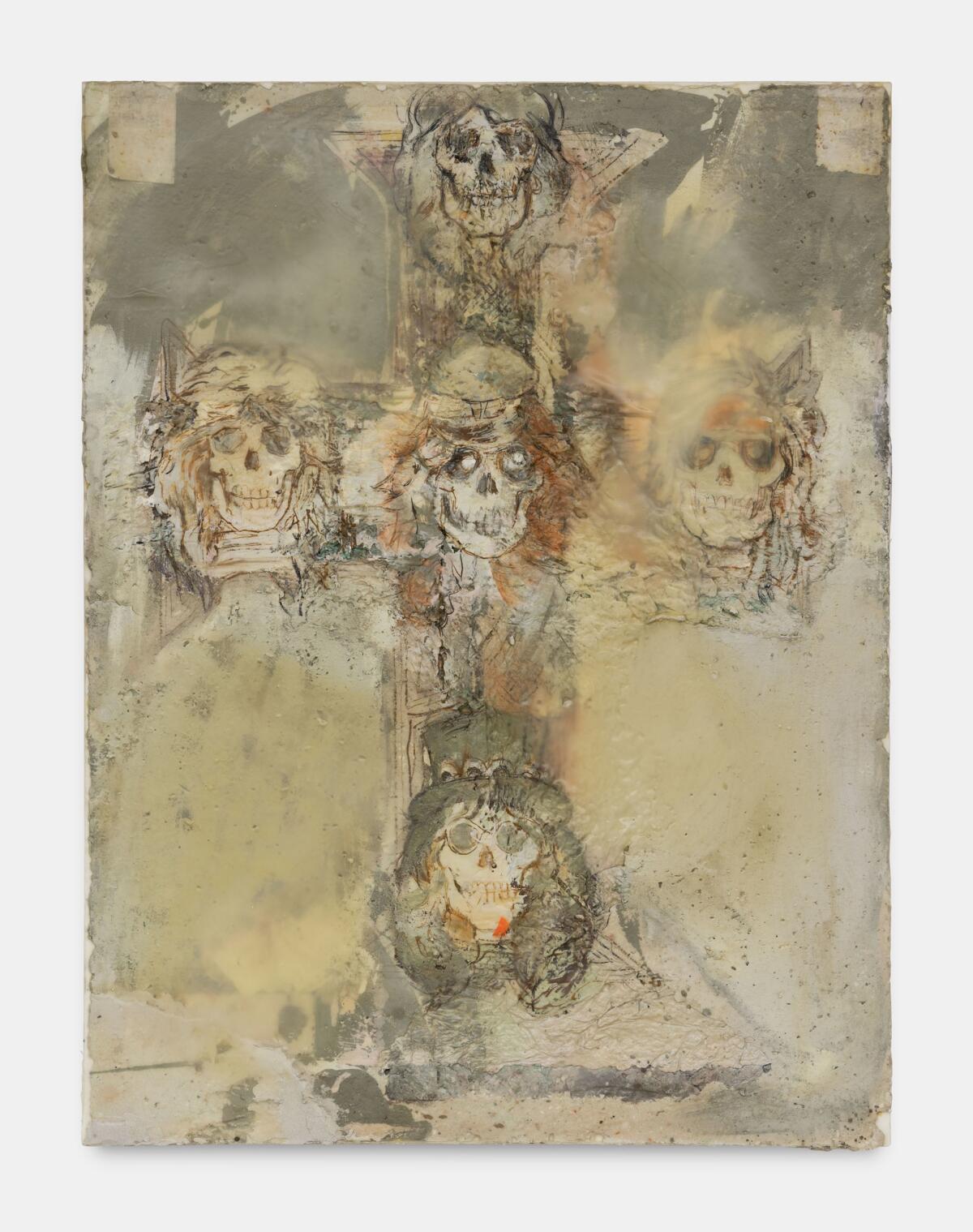

You started with the big guns! [laughter] So, first of all, the consecrated context wasn’t my main concern this time, but I liked the irony of dealing with the issue of idols again. Especially if you remember my show that took place a few years back, Iconoclasm (Beijing, 2010). It was about the notion of figuration in the Western world.

Christianity has experienced periods of iconoclasm – the religiously motivated destruction of works of art, especially figurative images – for example, the Byzantine Iconoclasm of the 8th and 9th centuries and what Martin Luther termed the “Bildersturm” (picture storm) during the Reformation. The basis for the deliberate destruction of pictures and sculptures in Christian churches at the time was the idea that making and using images for Christian worship was contrary to the word of the Bible, in particular, the second of the Ten Commandments: “Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image, or any likeness of any thing that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth: Thou shalt not bow down thyself to them, nor serve them” (Exodus 20:4-5).

The Second Commandment is directed against idolatry — worship of a cult image or ‘idol’ as though it were God — and is what lies behind both Christian hostility towards images and the Judaic and Islamic rejection of image worship. So, I was also intrigued by the idea that Western art in its entirety is basically blasphemy, according to what the church used to say for a few centuries until they didn’t say it anymore. The official doctrine has changed. Narratives evolve constantly. Kill your idols.

In the press release for the exhibition, I read that “Basilica San Celso’s many transformations are testimony to the history of Milan over the centuries.” The idea of transformation is close to your work; it resonates with your methodology. It makes me feel this link with the place isn’t accidental. Also, the word “transformation” itself is interesting because it’s neither positive nor negative and depends on the person who is using it..

It’s hard to comment on something so fluid, as you noticed. Good observation. I couldn’t agree more. Change and constant evaluation are crucial to my practice. It’s a drama, but it is what it is. I would like to be one of these German artists loved by gallerists who have six impressive round sentences to describe their art.

I know what you mean, but to me, it feels fake. These figures are products, and they aren’t inspiring. They start here and end there.

I call it “Euro art”. Yet, it’s like a dream I’m chasing. Something very firm on the edges, not as hazy and blurry.

Remaining in the same area of interest, and referring to your past, I couldn’t find information about what happened with Piotr Kurka’s Dog in the exhibition “The Dog in Polish Art” (“Pies w Sztuce Polskiej”) at Galeria Arsenał in Białystok (2003).

These are prehistoric times, 2004 – a show in North-East Poland, a region known for its patriotic environment, for lack of a better word, nationalistic, some would say. It was a group show at Arsenał, and Andrzej Fedorowicz censored Kurka’s work. I don’t know if he was a city official then, but he was a local leader of the far-right party. I think the rest of the artists withdrew their works as an act of solidarity with Kurka. A couple of months later, I took part in a group show, a student exhibition at the same venue, and referred directly to these events. This was one of the first opportunities to show my work in a decent place. I referred to Kurka’s censored work by showing a dog cage with a plate saying, “Beware of the dog, censorus all-polus, beast, do not pet.” Eventually my work targeting this previous censorship was censored again by the same guy, the same group of people. And the worst part is that they didn’t even understand the irony of the whole situation!

And what did your work respond to exactly?

I didn’t actually see Kurka’s work in real life. It was a long time ago, and I only know it from a description and some documentation. But from what I remember, it was a dog’s silhouette, and when you looked closely, there was a peephole in the dog’s butthole. When you looked through it, you could see priests or something satanic, the worst kind of blasphemy, Kyrie eleison. Real Christians got offended or at least acted like that to score a few political points from this move.

Did Kurka see it? Did you talk about it? And are you still happy or proud of this work?

I’m sure he did. I never spoke to him about it. But, yes, I always thought this work wasn’t bad, it was loud and it made it to the evening news. When I was making those semi-conscious decisions that I am going to be an artist, I always thought about the art world as more of a rock ‘n’ roll scene. I was looking up to communities like Warhol’s Factory, The Velvet Underground & Nico, hard drugs, musicians, actors, politicians and junkies, talented and cool people of all sorts hanging out together and experimenting, trying to bring a change, you know, a good platform, talented people of all sorts being actually cool.

By being cool, do you mean having fun and actually enjoying it?

Yes, that too, but also having that particular attitude, saying shit, being provocative and offensive to some, being avant-garde in a good way by being honest, like most of the great artists, who were over-sensitive and narcissistic, but also able to see things like social change a decade or two ahead of their own times. That was my — some would say — naive idea of the art world, which now, for the most part, resembles more of a real estate business, previews of good-looking merchandise, price charts, insider trading, etc… Still, it’s the best of possible worlds.

You described the time and place you were growing up as “post-communist, underdeveloped Poland.” It was inspiring for artists, there was a lot of freedom. Now, when we’ve gotten to the point when everything can be sold, it has become the way you just described. So in a way, despite all the bad press, it was a good time back then.

These are always good times. The art market didn’t exist, those rules didn’t apply. Right now, Poland is still a great place to make art because it’s so unbalanced and kind of uncomfortable. Are you familiar with this black-and-white picture of a protester from the US with a banner saying, “I can’t believe I still have to protest this shit”? — this is Poland in one picture. On the one hand, the last 30 years have been a period of unbelievable economic growth. On the other, the social and cultural change seems too rapid for some. So we are going through our own cultural war with our inner tribes and rhetorics that seem to be a couple of decades behind. When you travel a lot, and Poles do, many come back to Poland after living abroad, and they find it shocking. I’m not talking about Warsaw. Warsaw has changed; if it wasn’t for the weather it would have been one of the greatest cities in Europe.

What about Poznań? Is Kisielice still active?

I just opened a show with Cezary Poniatowski in Poznań at Galeria SKALA. It’s called Native Speakers. It was good. I wasn’t there long enough to get frustrated, and I really liked it. I didn’t go to Kisielice; I heard it is still active, but it’s a different crowd, and you need a password to get in. But there are other cool places. The whole city seemed very organic, grass-roots, and less pretentious than Warsaw can sometimes be, but still… we got kicked out of one of these popular places because we had our own alcohol.

You seem ambivalent toward Poznań and Poland in general.

I love it, and I hate it. I miss it, but I’m fed up with it quickly. Visiting is always fun. Good friends, good food. I’m a big fan of the Polish countryside. But on the other hand, I know they still chain dogs, burn plastic in their furnaces and eat animals.

You don’t?

I do, sometimes. [laughter] But my girlfriend dislikes that honest brutality of the countryside. So I feel guilty when I have to bring her down there. I mean… but I get it. I know where it all comes from. That’s where I’m from.

The beliefs these people hold are somewhat naive and pure. They have cable TV and watch the news, but besides that, this pre-Christian verbal culture is still a part of their lives. They still gather in one of the rooms or kitchen and talk, mention thousand-year-old names, arguing about the details of these ancient stories. They didn’t read about it in books. For example, I googled some of the names I remember circulating in my childhood a couple of years ago and figured out that they come from Slavic mythology. Mamuna, Przyducha, and Death with a sickle are coming to take babcia Bukowinkowa away. Satan in a fox’s form, other bizarre creatures, protective deities, and their abilities. Moonshine-infused gatherings in this deep southern Polish countryside. Accordion tunes in the background and me carving a wooden stick with a massive knife — being both scared and fascinated by the stories.

Do they actually believe in these otherworldly stories?

Yes, that seemed obvious and very convincing.

I asked you about the exhibition space, and you said it didn’t influence you in this very emotional religious sense. So this aspect isn’t something that would bother you or that you would want to talk about in reference to your art?

I’m very bitter when it comes to institutionalized religion. If I had to carry on, we would have spent another hour talking about my resentment towards institutionalized religion and the Roman Catholic Church as a well-lubed machinery. Poor choice of words, I know. I don’t think this is the time or place to discuss it. It’s not that I don’t have an opinion. I do have it. It does bother me a lot; it is present in my art but I don’t want to be didactic about it. It’s a personal thing for all of us, I believe. I realized that I’d harmed people unintentionally by being too direct or assuming stuff too quickly, and I wouldn’t like to do that again.

Your exhibition, Places I had no intention of seeing (Zachęta, 2019), although I haven’t seen it in person, seems to resemble this schizophrenic-like storage room that we see in pop culture, like in the movie “A Beautiful Mind”, full of scattered pieces of materials with personal stories, gathered maniacally in a wooden hut in the back of the yard. It’s an exciting perspective. On the other hand, what I saw in San Celso was very, very different. This display was refined, non-chaotic, non-aggressive. Its narrative was almost linear, unlike your previous work. This current exhibition looks pretty unusual compared to what we could see before. Is this “calming down” a curatorial manipulation to align with the space, or is it a moment of conciliation with yourself, an attempt to sum up, some sort of maturation?

That’s a good point. These were totally different shows for many reasons. Places I had no intention of seeing at the Zachęta was excellently curated, and this show was, to this point, the most important one for me.

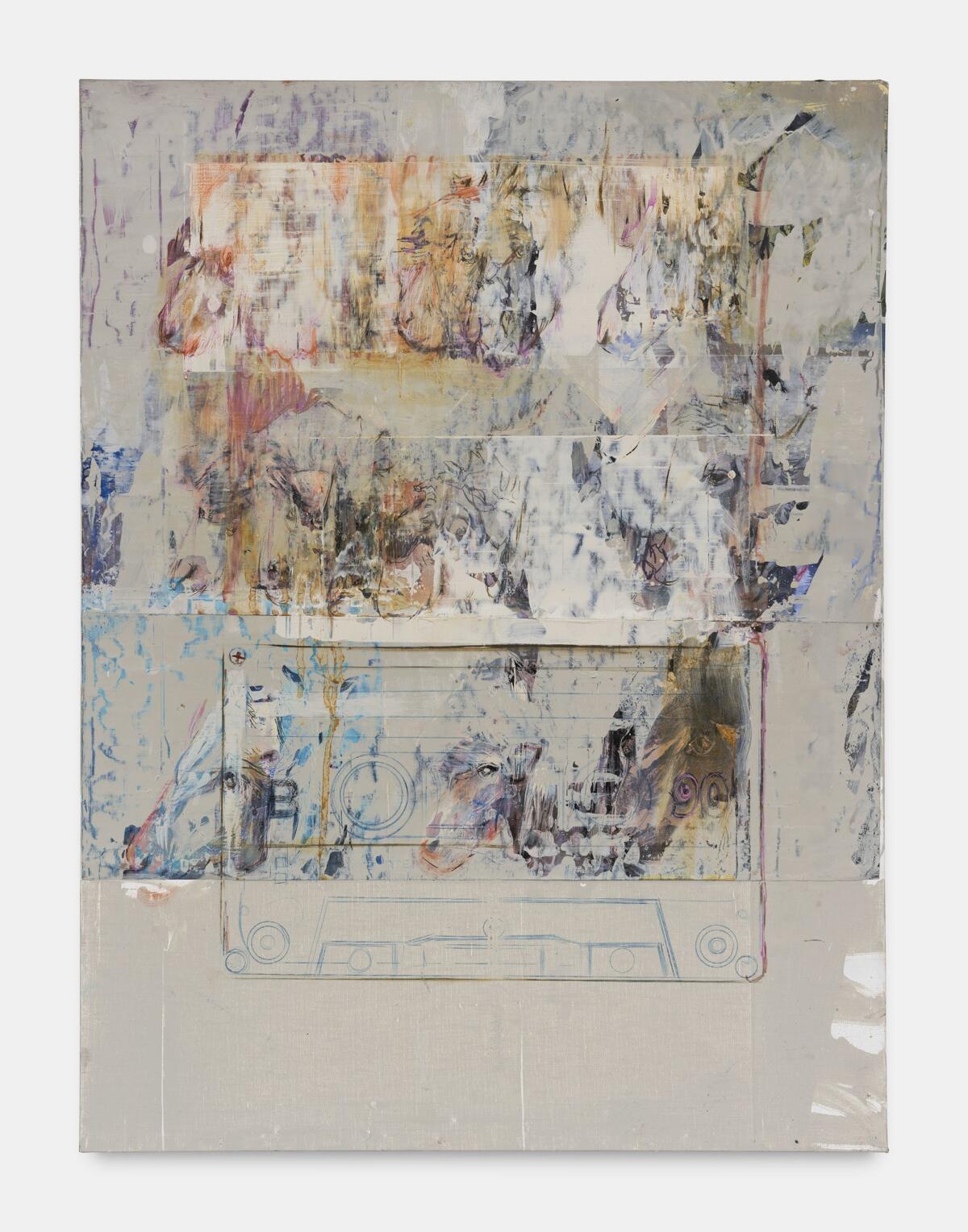

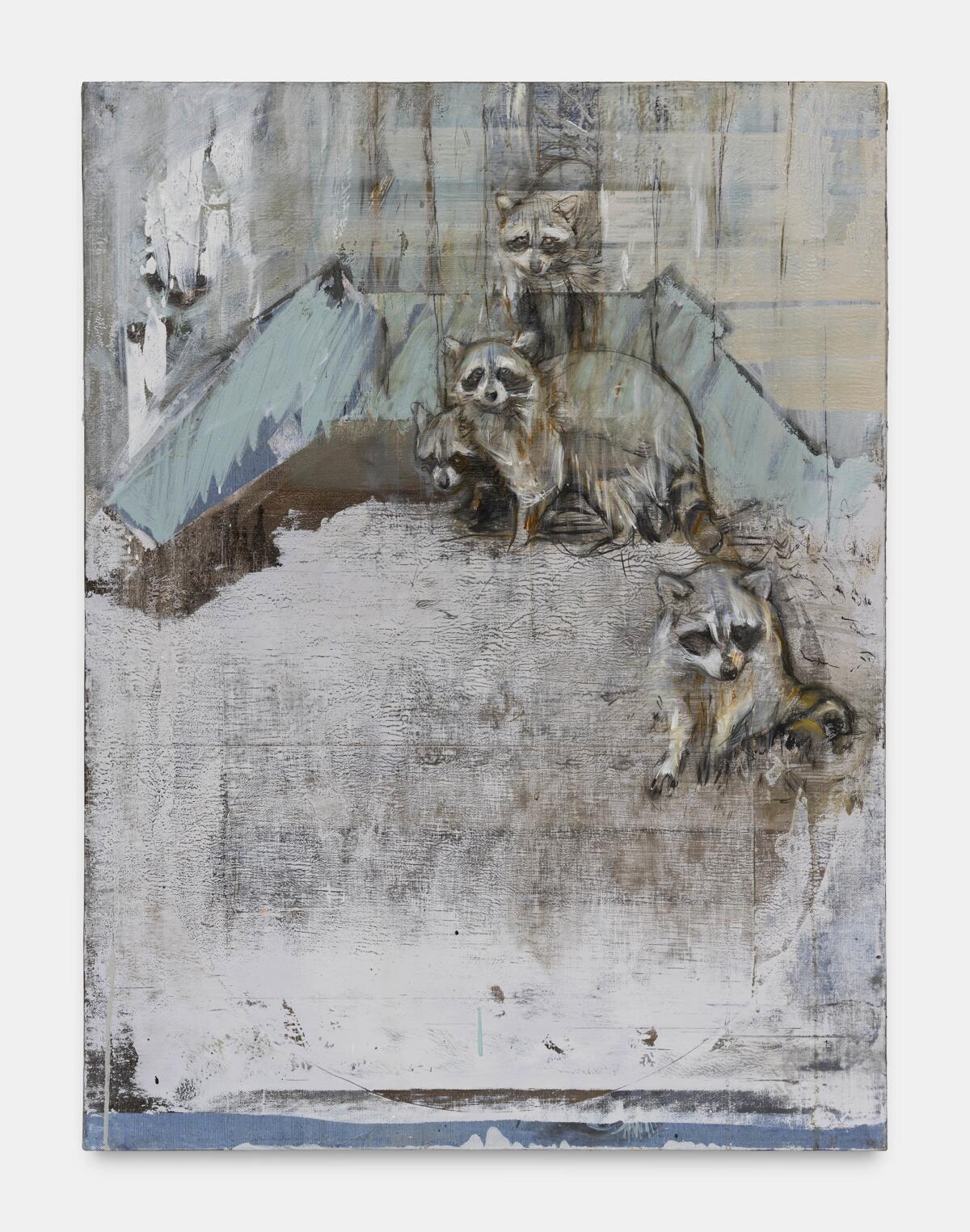

There were three spaces, three acts — a road to madness. The first was like a chamber of wonders, with many details packed into this organized structure. It resembled the 19th-century idea of Wunderkammer, displaying curiosities and freaks of the world in one place and showing off all that you have seen, achieved, and gathered along the way, an attempt to describe the whole world in an encyclopedic structure. The second space depicted the contemporary lack of a hierarchy of the information we are absorbing today, with the imagery and narratives coming from an abundance of various sources and places, for example, stuff you see while going through your Instagram feed. We spend so much time scrolling through pics or memes rather than obtaining actual knowledge. It’s different from a library, where stuff is organized and labeled; there is either fiction or non-fiction, simple as that. There’s nothing in between, you can’t go wrong with it. Here, on the other hand, everything is the same and has similar value. Cancel Culture, flat earth, Ukraine, cats, dogs, and raccoons… you tell me… And the third space was just plain chaos and madness, multilayered, shattered, an echo chamber of scars and leftovers. That exhibition was like a wall to me. I hit it and I couldn’t go any farther. I had to figure out something new. It took me a while.

I’m working on a bigger project right now. Kill Your Idols at San Celso is a teaser for a more extensive structure with many different angles and narratives intertwining. As you noticed, this exhibition seems more linear. It’s like a movie trailer showing what you are going to see soon. So I can’t disclose too much since I would still like the audience to come and see it, right? This year we want to show more trailers like this, with different sets of works, in various locations, a flying circus, sort of a touring show.

I see. It explains a lot.

You get hints. The discrete manuscript in this exhibition provides you with the narrative backbone, such as the story of Noriega, a Panamanian dictator who was overthrown by the US at the beginning of the nineties when the Iron Curtain was crumbling in Europe, so nobody paid too much attention to what was going on in the Caribbean. Still, the US was basically cleaning up its backyard and taking advantage of becoming the only hegemon back then, and no one could say anything to oppose it.

I wouldn’t like to disclose too much, but it has various angles. One is this literal anecdote above, which seems almost unreal, and resembles a Hollywood movie script. The use of festival-sized loudspeakers and heavy metal music that I loved as a kid, to smoke the dictator out of his hideout— the notion of soft power and weaponizing pop culture to achieve imperial agendas. This layer is something everyone can Google and can relate to or recall from memory.

There is also a more personal angle. These are my memories of this era because, for some reason, I remember these events clearly, even though I was ten years old. For me, this exhibition is also about the end of an era, about this dramatic evaluation that comes with it, on both a broader universal and a very personal level, figuring things out. Axl Rose, the author of the songs used to terrorize the poor dictator — whose sculpture I rendered in marble — was one of my greatest childhood heroes. My room was plastered with his pictures. A true idol. Now he looks nothing like the poster guy, all worn out and weary, can’t even sing anymore. He’s obviously not much of an idol for me anymore, unfortunately. I guess I’m pursuing new ones.

And then there is this broad spectrum of various angles in between, different approaches to this period. It was about three decades ago, and I believe that this era, the Unipolar Moment, as some call it, or Fukuyama’s The End of History that followed these events, is now definitely over, and so is the reality and socio-political structure we all grew up in and took for granted. The continuing escalation in Eastern Europe, Iran, the rise of China, economic decline, and Idiocracy in the West are just a few symptoms of a bigger shift. And I didn’t come up with this, it’s simply happening in front of our eyes, and we all can feel it. Tomorrow is unknown. The whole planet will look different. Mark my words, kids. Great time to evaluate. Sum up the achievements.

I often hear it from people in my circle, and I always wonder if it doesn’t come from a place of psychological egocentrism. You know how we consider it funny that three to five-year-old children think that when they see something, their mommy also sees it, even if she’s in the other room? So maybe the end of the world you describe is just a phase people go through in their life?

Sure, I mean, yeah, no. I believe I’m entitled to create this whole alternative grand narrative. And just because mommy doesn’t see it doesn’t mean it’s not there.

“Entitled” is a good word. [laughter]

Yes, it’s arrogant, but you need to be arrogant to be an artist. You need to take advantage of some of the predispositions of your personality to dare to say stuff out loud. I’m hiding behind my paintings. I’m not used to talking much about what I’m doing and what I believe in. I have the luxury of expressing myself through my art, leaving a broad margin of anarchy for people to interpret. So I’m relatively safe. But on the other hand, I would like to be understood better, to be heard. I’m convinced that the world we know is over. And it will not be Armageddon, don’t get me wrong. It still might be, though, but I don’t believe in nuclear holocaust. Yet, the world is definitely going to be radically different very soon. The entire paradigm changes, and so do the narratives.

Remaining still in curatorial decisions, I feel that the less you show, the stronger the individual works influence the viewer. For example, in this exhibition, there was a large painting with “malarstwo” (“painting”) written on it, which you hung in the front, just at the entrance. It was the first work a visitor could see, even from afar, before entering the Basilica, so it was probably the most intense one (not for me, though; I was the most moved by the contour of Poland). Why is the painting “Malarstwo” so crucial for this exhibition? Please also say more about the writings you use in your works. I know you sometimes sign your work on the front of the painting.

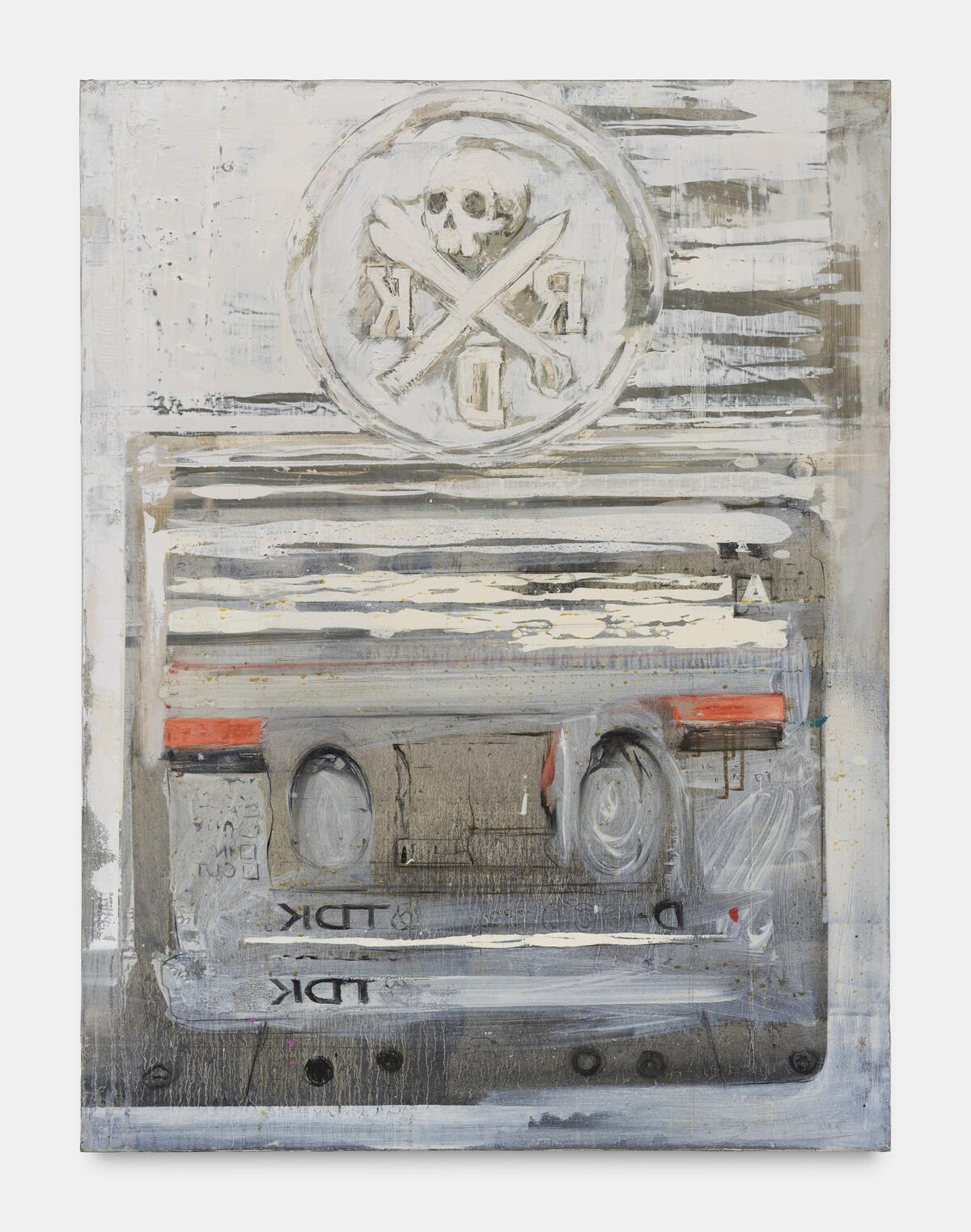

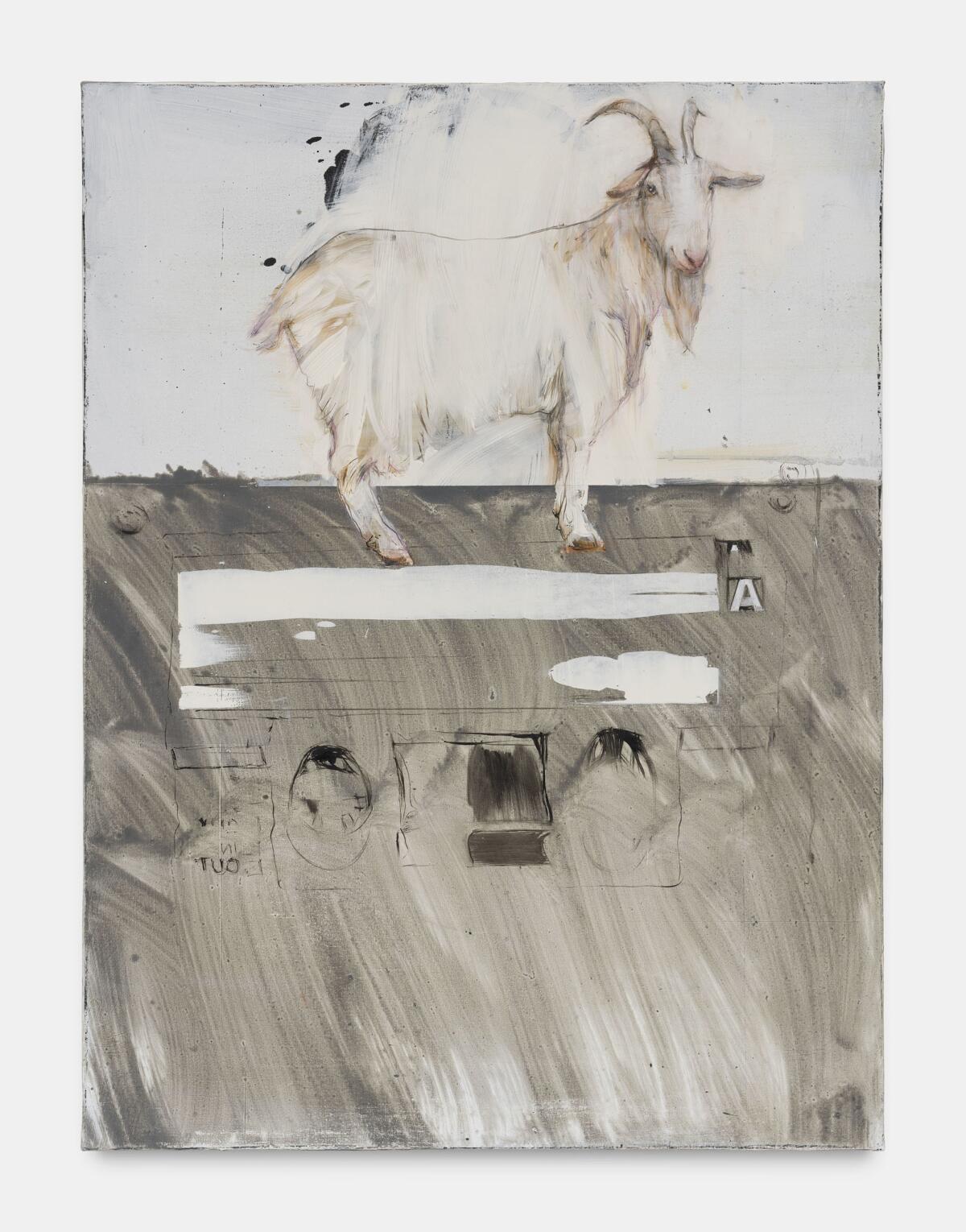

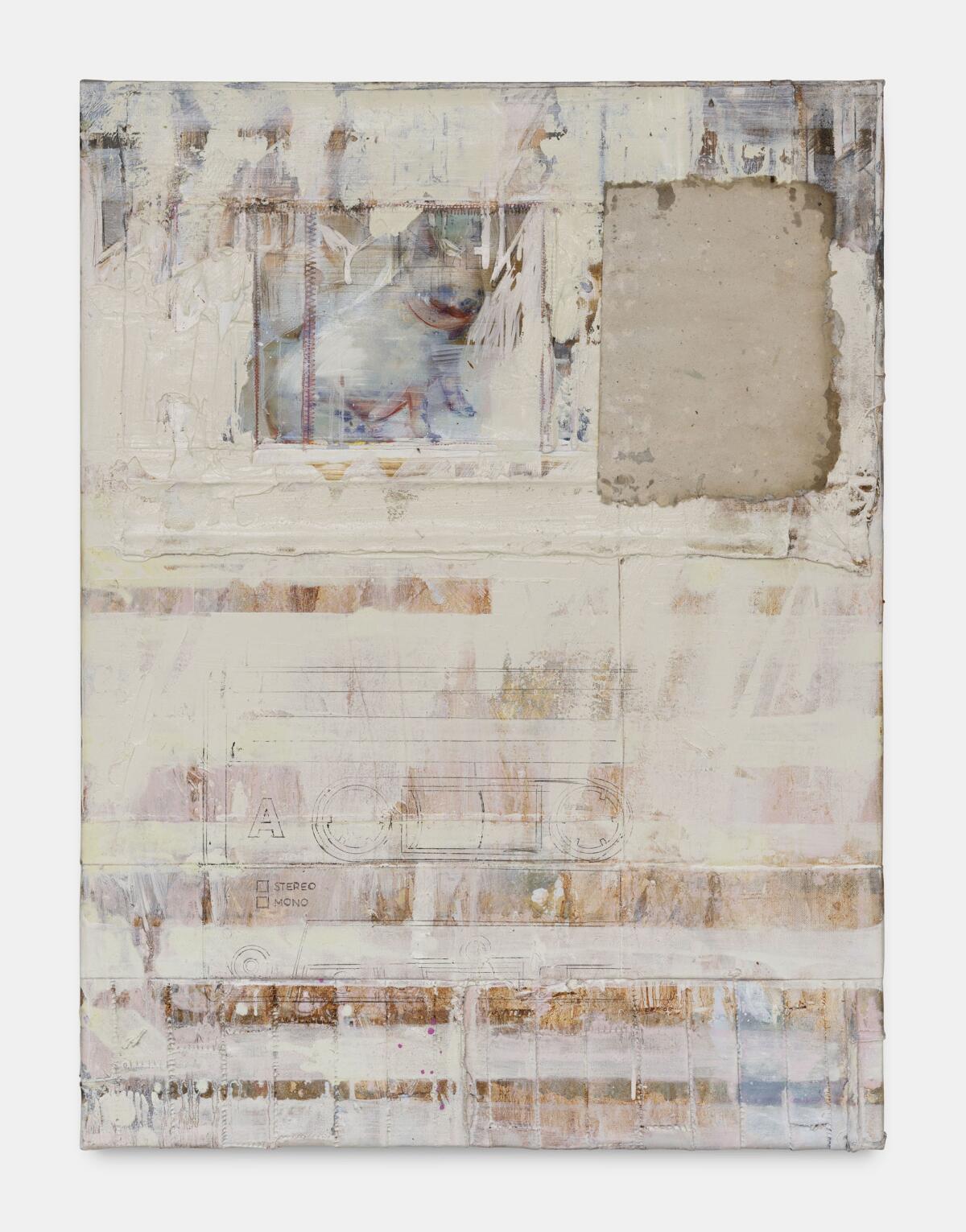

The smaller pieces presented in this show, “Noriega Playlist,” add a personal angle to this exhibition. In the 80s and 90s I used to get mixtapes with handwritten titles and names of the bands. My dad was in the US then, and he and my uncles would send me hard rock and trash metal albums recorded on tapes. I remember how exciting it was to unpack these parcels and then play this music that wasn’t available back then at home: Guns and Roses, Iron Maiden, Bon Jovi—all this shitty music that ruined my taste and that I still find beautiful and that I listen to, not ironically. These smaller paintings in the exhibition are album covers I used to create and paint back then. I wanted to revisit this childhood experience. So I painted a few, and now I’m working on some new ones.

On the large painting, I wrote “malarstwo” using the trash metal band Metallica’s font. “Malarstwo” comes from wanting to create an illustration for the music and translate this trash music into visuals. Most of the works in the exhibition are translations from this physical medium of a cassette tape and a recording process: layers on layers on layers. Magnetic tape isn’t digital, and once you get rid of something by recording something new over the existing song, it’s irreversibly gone. You lose one thing, and you get something new instead. The painting process in this show was the reflection of that idea. But it was also coming from the concept of the narratives, of how they function in life today. When the new one emerges, it covers the old one, making it obsolete. Last week’s news is old news. And there is this constant stream of updates. My art is about that. So, I started with this idea of blurry edges and ended up firmly stating what my art is actually about. [laughter]

What struck me was that you say kill your idols; I go to this church and the first thing I see is the painted word “malarstwo.” Maybe it wasn’t planned…

Yeah, that was in the back of my head. Dead medium, dead painters, their skulls; dead Holbein, Friedrich, Rothko, some of the painters I killed in the painting were still alive apparently. I wasn’t aware of that at the time. Painting was proclaimed dead so many times that nobody pays attention to this anymore. I find this idea very liberating. Once something is dead and desecrated, you can do anything to it because no one seems to care anymore. And when it functions parallel to new media, not only photography but also video, TikTok, etc., its nature is evolving, and nobody knows what painting means anymore, what its expanding definition actually is.

What about text in general, and your signature?

My signature is just an image, as any other, a representation of something, like a selfie or self-portrait, a study of myself or my current state. I’ve been painting since I was able to hold crayons and brushes. At some point, it wasn’t a hobby anymore. I became a professional. People started to consider it art and pay for it. I painted everything already. Not once, but multiple times. I needed to come up with new ways and methods, otherwise I would get bored. Painting is the only thing I have stuck to for so long, keeping me alive and sane. Painting your own signature is like painting yourself, so it’s not even the most original idea.

Giovanna Manzotti writes in the curatorial text about “layers of collective memory filtered through an autobiographical lens,” referring to your work. I feel that your paintings put me in some distress. I feel that I’m becoming, maybe not to the point of crazy, but not completely calm, either. I even wrote in my notes that we are “falling victim” to your paintings. Given the personal and autobiographical source of inspiration, this must be a natural state for you. I also see that you cherish and treat this part of you as a value. So, as an active artist and a person living your everyday life, do these spheres affect each other? Do you find yourself unwilling to resolve this chaotic part for the sake of your work?

I know what you’re saying. Welcome to my world! [laughter] That’s very flattering what you said. I used to go to therapy back in the day. In the beginning, I was scared that I would be robbed of that most valuable part of me, the neurotic rage that was always with me and makes me scream when I see electric wires behind the computer or when I need to update the operating system. That brings a lot of tension to my house. I have this anger and rage that I think was the modus operandi for most of my not even career, but way before that, and it’s still there. It’s more structuralized now since that therapist made me more aware of where all this is coming from and why; mommy and daddy issues and childhood traumas. Emigration didn’t help either… character building; there is a lot of frustration here. And then you have the layer of the art world, where everything is so aerodynamic and shiny. Everybody is so superficially polite, wears Margiela, and comes from a different background than I do. So, yeah, I cherish it. But my biggest, ultimate dream is to put on a very elegant show. The one at San Celso was the most elegant thing I was able to produce at this time. But on the other hand, I’m aware that I’m never going to achieve that, so there is always this weird tension that keeps me going.

I remember one mainstream film director once said therapy makes you lose it, which is why he wouldn’t go. I also see in my personal experience what my therapist does to me and how she normalizes me, which is not so cool.

That’s why I was lying to the therapist. [laughter] I made up whole stories and characters. I kept this part of me that keeps me going for myself. But she made me a bit of a different person anyways, so what you’re saying about normalization brings me to another conclusion. I believe it was Noam Chomsky who said that the smart way to keep people passive and obedient is to strictly limit the spectrum of acceptable opinion but allow very lively debate within that spectrum. That’s coming from a renowned Ivy League professor, so it’s not me saying that. It’s not against any novel discourse; it’s a smart thing to say. I didn’t find some things offensive a decade ago, but I no longer allow myself to say them. When it comes to my art from that era, I am not showing particular works anymore because they came from somewhere I don’t want to talk about; it takes too much explaining, and people don’t have time for that.

Part of your biography that you most often refer to is the years you were growing up. You often talk about the absurdity of the contrasting environments you experienced as a child, that of a “post-communist underdevelopment and late capitalist dystopia.” These topics are, in fact, outstandingly inspiring and popular among artists, but it’s even rarer and more remarkable to experience them both. I can see why what you went through has fueled you for a long time. You say, “Two pillars melting in me and creating a creole amalgamate, oftentimes difficult to cope with, but which gives you a particular ability to speak a lingo nobody fully understands yet finds familiar.” I imagine that after we lived with our childhood traumas for thirty or forty years, some things get processed and digested over time. So, what inspires you currently?

`I want to say I’m done with it. Not entirely, maybe, but it’s not as much of a burden anymore. I kind of dealt with it. So are you asking about the new source of frustration? [laughter]

Of interest.

That’s pretty much the same thing. But I think what is different now is that I took a few steps back to get a better view, a different, broader perspective on what we are used to calling the world, basically the Atlantic West. I notice the existence of other worlds or pillars of the cosmos, i.e., that part of the world we come from is particular. We don’t even have a good name for it. Is it Central or Eastern Europe? It’s a fly-over Europe. People hear about it but never go there. You mentioned that the painting with the outline of Poland was the most powerful to you at the exhibition, for to me too. It’s titled “Eastplaining,” a reference to the buzzword “Westplaining,” coined by Central European academics. They coined the latter to describe this patronizing, persistent and frustrating feature of Western commentary on the post-communist countries in the context of the ongoing war. In the “Westplaining” framework, the concerns of Russia are recognized, but those of Eastern Europe are not. Eastern Europe can be explained, but it isn’t worth engaging with. So there is this underdog complex—we became part of the West and accepted all its downsides, but we still don’t get the full benefit of it. We’re not a colony anymore, but we’re not handsome or civil enough to sit at the table yet. So “Eastplaining” is a project that explores alternatives to white male dominated, linear, and Western-centric forms of knowledge. An extensive grand narrative, a complex atlas-like framework. Where panoramic textiles, maps, objects, sculptures, and architectural interventions materialize.

So, how do these Westplaining/Eastplaining ideas inspire your painting?

There is this constant tension. It became visible on February 24th, 2022, when Europe was dealing with a major war in its direct vicinity, and there were different approaches to it. People in Eastern Europe reacted differently than those in the West because the West had more to lose. To us it was clear who was the bad guy and what we needed to do. We can experience this tension in many other situations as well.

This rich Eastern European background you are talking about makes me feel lonely abroad.

I hear you. I have had the experience of living in the West for a long time, and yes, you cannot go too deep when you talk about yourself because nobody really cares, but on the other hand, you’ve got so much to offer! So pick the juiciest chunks, preferably the most exotic ones, and boost them; make a big deal out of your folklore, pickles, and squatting.

I curated a few exhibitions with Polish artists abroad, and while these works fascinate people, explaining them was…

Frustrating.

Impossible. You don’t do it. So, my penultimate question, referring to the title of your current exhibition: Do you have idols in art?

That’s the most common and the most challenging question. I do, and I don’t. It comes and goes. I don’t have an album or an art book that I keep returning to. I love Dutch Renaissance painters. American painters from the mid-century, 60s and 70s. I came up with the idea of being a professional artist fascinated by Warhol’s lifestyle. Not even his work but the community surrounding him: musicians, junkies, politicians, curators, this whole social situation. Rauschenberg’s work, Cy Twombly, Albert Oehlen, old-school Polish art, the Young Poland period, Wojtkiewicz, and Wyczolkowski and Neue Wilde gestural expression, Arte Povera. But my art is about life, not about art. I find inspiration elsewhere. I’d love to paint the way Huellbecq is writing. It’s free, magnetic, superficially cynical, yet very romantic. He believes in love too. Deeply unprogressive.

In the text for Kill Your Idols, I read about the Axl and Noriega’s fall, about them getting weakened, and I can’t shake off the feeling that it must reflect your own current experience or point of view. But, on the other hand, the feeling of everything falling apart, getting rotten, and ending, would be tremendously depressive, and yet, I didn’t feel that when spending time among your works.

Because it’s like a cycle of nature. Once it’s rotten, it turns into fertilizer.

These are, actually, the exact words of my question; I described it as a circle of life. Giovanna Manzotti also writes that “stories chase each other.” And the overall vibe of the exhibition is, maybe not optimistic, but at least neutral.

Neutral is not a word to describe what I’m doing [laughter], but I know what you’re saying. Ambiguous, I would say. I’m not neutral. I’m constantly judging and making vivid and involved commentary. But, on the other hand, I don’t believe we are able to stop it; the machine is fully running, and it’s too late. It’s downhill right now, it’s happening. The more neurotic or sensitive people, or those who read the economic analyses, are more aware of what’s happening. We must be better prepared for it and come up with ideas to function in a new reality. That’s it.

I’ve read a few articles about you, and almost every bio describing where you lived at the moment was different. Since being constantly on the move is such a big part of your story, can you imagine what you would do if you were stuck in one place? Let’s say you spend your entire life in Białystok.

No, Białystok, no. [laughter] With all respect to the people who live there, my best friends are from there, but hell no.

It was just an example because you had an exhibition there. [laughter]

I know, I know, I’m kidding. I plan to move to Rome, and I will have to update the bio. The show at the Zachęta that we presented a couple of years ago was about this constant flux of images and my nomadic lifestyle, however pretentious this word sounds. My family moved a lot, and I moved a lot even more. When somebody asks me where I’m from, I used to oversimplify and say that I’m from Warsaw. I’m not from Warsaw, but I no longer have an answer. I live in Belgium. I don’t hate it here. But it’s not where I’m from.

Can you even imagine yourself without this? I know it’s a very abstract thought.

Without this position in a bio?

No, without this experience.

I would be a different person, for sure. This interview would be much shorter if I lived in one place instead of many. I have a dream, a plan to have a home and a massive studio next to it. I’m working on it. But it’s like with this elegant show that I’m working on. It’s an idea, or rather a goal. I’m still hoping I’ll get there at some point.

Edited by Ewa Borysiewicz and Katie Zazenski

Imprint

| Artist | Radek Szlaga |

| Exhibition | Kill Your Idols |

| Place / venue | Basilica di San Celso |

| Dates | 26.09 - 07.10.2022 |

| Photos | Lorenzo Baci |

| Index | Basilica di San Celso Dobrosława Nowak Italy Lorenzo Baci Radek Szlaga |