The interview was commissioned by and originally published in SZUM magazine.

After his death Robert Anton was pretty much forgotten for decades. Why?

Anke Kempkes: I have a little gap in the narrative myself. We know Anton died in 1984, but what happened after he died? What was the immediate reception of his person in the 80s?

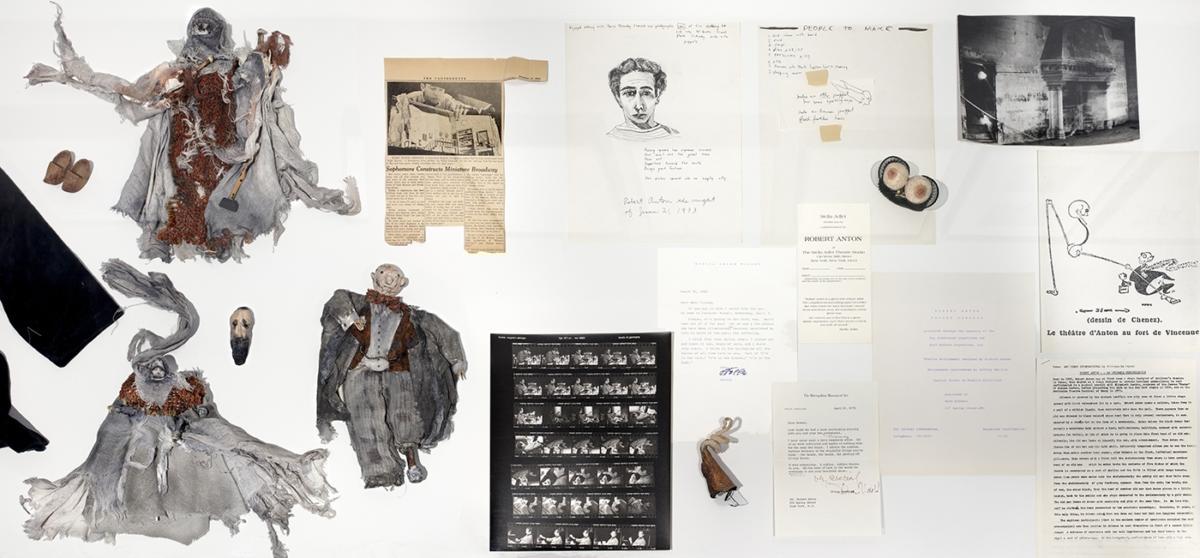

Bette Stoler: He left me the collection. At that time I was running a gallery in which I showed the figures of clowns, I also had drawings I exhibited before in my previous gallery. There was a small group of faithful followers of Anton at that time. People didn’t know about it. In order to attend the performance you had to be given his number to call, it was all very clandestine. And then you get a call back at the day of the performance, telling you if there was space for you. After he died, I contacted several museums all over the country and in Europe, starting with Metropolitan Museum of Art, because he performed in Europe a lot. I wanted them to exhibit his works even for a week, to do something so that this work didn’t just go into the archives. MoMA, Whitney, they all knew this. All the major curators from New York had seen the performances and they were big fans of his works, yet they couldn’t guarantee anything. It was the same situation in Europe. I couldn’t just let his works become undiscovered for years. Ultimately I put it away thinking: “OK, I will keep talking about it, and eventually someone would become interested. Which didn’t happen. Then I went for a grand tour around Europe, I went to every puppet museum, I would have donated the work. In exasperation I put it away. If people would call me, I would show the collection. I was always available, but I just didn’t knew what to do anymore, because at that time it was not fashionable, and you know the art world is all about fashion. So I just held it until I realized that the time was right. Then I took it out and that’s when I met Anke. She understood this collection in about one second.

AK: I think this reflects actually how the art museums are not prepared to deal with such a specific kind of art that Anton collection represents, even now with all the new established departments of performance art. I had this conversation, for example with Jay Sanders, who was at the time a brand new Curator of Performance art in Whitney Museum. He told me that the Whitney has not resolved yet for example how to collect performance related objects. Jay is a total expert in experimental, underground theater from the 70s in New York. He’s a trustee of the Richard Foreman Foundation for example, and Foreman’s theater was related to Anton’s work in New York, also very surreal, very experimental, having a lot in common in this specific kind of European sensibility. He was also always interested in Stuart Sherman’s work in New York in the 70s, another artist who worked with the miniature setup, yet quite different from Anton’s, farmore minimalist. Sherman had a little folding table, he used to go to the Central Park with it and with his suitcase, just to set it up and create a world theater on the table. He was however more connected to the art world, Babette Mangolte, the performance photographer I have been working with since 1999, photographed and filmed some of his works. She worked a lot with the 1970s scene in New York, she also made a film about Edward Krasiński’s studio. I learned almost everything about 1970s avant-garde, minimal dance and experimental theater from her and then from the artists she connected me with. So I had been prepared, in a way, quite well for this milieu in New York, which Anton’s was part of, and it was, I think, not completely by chance that Bette one day came to the gallery to show me these exhibits. And I will never forget this; we didn’t know each other at this point, she came to the gallery with the suitcase which is on show at the Foksal Gallery Foundation, and all the heads fit into this one suitcase with which he traveled. Then Bette unpacked these heads and I was like: “what on Earth, this is so amazing!”. The craftsmanship was stunning, they were amazingly elaborate sculptures, I could see these surrealist, post-Artaudian, and the camp qualities of the works. One could probably write an interesting article about Anton’s connection to Jack Smith I think. Did Robert knew Jack Smith?

In order to attend the performance you had to be given his number to call, it was all very clandestine. And then you get a call back at the day of the performance, telling you if there was space for you.

BS: No. He curated his life, he was very aware of every move he made, he projected a very androgynous figure, he always wanted to remain in the background and did not want to be associated with other artists of that time really.

AK: But he was connected with quite a number of artists, we have this in the testimonies, but generally he was maybe more socialized in the theater world.

BS: Yes, but he refused to do anything he wasn’t in charge of, and that didn’t match his sensibility in a hundred percent. He really kept himself as pure as possible.

AK: People kept asking me at the exhibition if there was a connection in the 80s to David Wojnarowicz or Robert Mapplethorpe.

BS: Mapplethorpe photographed in my gallery all the time, I knew all those people, I was associated with them, but Robert was not.

Why was he also so strict about limiting his audience and not allowing to document his performances?

BS: He wanted it to be a very intimate experience for everyone who has seen it, that’s why he only had room for eighteen people in the theater. And he didn’t want any documentation because he wanted to have direct connection with the viewer.

AK: You also shared a lot of his relation to alchemy in a personal, performative way.

BS: We spent years studying alchemy together. For years we would do rudimental experiments, we used to go to the library, find archaic manuscripts, read them and discuss them. Robert’s practice was very steeped in alchemy. He used fire and water, magically transformed puppets into completely different personas. He set something on fire and controlled the flame, just as he controlled everything in his life. In one spectacle, a cornucopia emerged from the fire . with fruit flies and then the fruit flies would disappear back into the urn. All these things were alchemical experiments for him, and each performance was slightly different. And the characters would change in each performance. That was to keep himself interested in this too, and he gathered a certain energy from the audience and could adjust the performance to that energy.

AK: And I guess that kind of an energy also was supposed to spread from him to the audience, they were the part of this alchemical experience. That’s why he also liked the Artaudian idea of the ‘theater of cruelty’, something very visceral, something you experience physically and emotionally. Photo or video mediation would have demystified the whole story, would have broken the magic circle.

This is a very unusual approach to a puppet theater; why would he do that rather than an actors’ theater?

BS: Because he felt he could control it. And from the time he was very young he created these dramas, these small universes, it was just very natural to him, the idea of puppets was appealing to him, and the idea of performance art was not. But he would never use the word ‘puppet’, that is very important. It was also an extension of what he saw in the world, what he thought of it and of himself. He liked the intimacy of that miniature world.

AK: We have all these press articles from Texas from the time when he was eight-nine years old in which he was portrayed as a child prodigy, they compare him with Michelangelo. His parents were quite well-off, educated, sophisticated bourgeois, they took him early on to Broadway plays in New York. After returning home he used to recreate remembered prosceniums of these Broadway plays in miniature artworks. Actress Linda Hunt said that he had told her he never wanted to control any space bigger than the space under the dining table of his parents, where he started creating his miniature universe. He didn’t want to control something like big productions, though all these things were offered to him. Even Walt Disney himself contacted him.

BS: Walt Disney actually gave him a blank check and asked him to become a manager in the department of special effects, to run this division at the time. He wouldn’t even consider it.

AK: He could have become the Tim Burton of the 70s. But it was not a concept for him. The same was the case with big Broadway productions.

Anton collected worn-out faces, people he saw in the parks and on the streets, particularly in the park that was close to his place on Upper West Side.

BS: He was offered to work with Tommy Tune, who was the choreographer and the director of Nine, which was a take on Fellini’s film Eight and a Half. Fellini, whom Robert met and talked to a lot, was one of his heroes. Still, he couldn’t get involved in that project, even though he was friend with Tommy Tune, because it could destroy his ideal of artistic purity.

How would you describe this miniature universe he created and characters that inhabited it?

BS: They changed all the time. They were all about transformation, transfiguration, and rebirth. Sometimes the rebirth was painful, sometimes it was a very joyous thing. It was about life as we live it in this world, it would magnify every emotion imaginable. People had visceral reaction to it, they tried to leave in the middle of performance, cried uncontrollably, or vomited. It was very intense and it hit everyone. No one I’ve spoken to has ever forgotten the experience.

AK: I think it’s also an amazing variety of characters that he created. We call some of them the ‘pedestrians’, he collected worn-out faces, people he saw in the parks and on the streets, particularly in the park that was close to his place on Upper West Side. There were for example retired opera singers, dancers…

BS: Major opera divas. The park was called ‘Needle Park’, because there were a lot of junkies there. It was everything, it was a microcosm, yet everyone went to this small park.

AK: You can see that in the works, you have the trash lady, you have these Puerto Ricans, in some faces you may think you see a kind of witch, but if you look closer, it actually looks like an old actress that had too much surgery. That’s the camp aspect of it. And you have these more archetypal characters, like the pope who gets degraded to the rank of the cardinal, then a bishop, and finally a blind man, who’s crawling on the floor trying to get the golden key. And the rabbi, the wise man from the desert, the Gypsy… And then you have these very tough ones, skeletons, the one that people in the testimonies always refer to as a Nazi, although Anton didn’t have precise names for the characters because they changed all the time. Everybody remembers ‘the Nazi’. And also of course the dancing skeleton that people referred to as the ‘Josephine Baker character’. We were asking people who saw the plays if there was any sound ever. And in fact there was a skeleton dancing to the rhythm of Cab Calloway’s song Minnie the Moocher from the 1930s. There was a Betty Boop animation in which there are skeletons dancing in a cave to this song. Anton was very interested in the early 1930s Hollywood cinematography.

BS: Often those characters, particularly the ones from as we called it Needle Park, were punctuated in different very intense scenes in the performance and they would offer a little comic relief. When we would least expect, there would be a dancing skeleton, or a Nazi peeing all over the stage. He would manipulate the intensity of performances in a very skillful way.

Animations from the 1930s, like those with Betty Boop, were very dark compared to later Disney films for example. They were related to the political situation of the Great Depression. Were Anton’s plays, with all those junkies and worn-out divas characters also somehow meant to be political?

BS: Not at all. No.

AK: Not even in a sense of transforming all the ‘degraded’ characters he observed, kind of deprived people from the streets of Manhattan into his anti-heroes? Don’t you think there is a certain political element in that?

BS: No. He was coming from very different place. He had a very wild and very sophisticated sense of humor. And a lot of this was derived from that place. It wasn’t making a statement about anything, it was just presenting, conveying what he observed in this world.

AK: But it’s interesting because I think at least in a certain revisionist kind of way there are motifs such as this ‘Nazi’, looking like taken straight from a George Grosz’s painting. I think there are certain references in the characters to Bob Fosse’s Cabaret, which is a very camp political narrative. In Anton’s Parisian play there were even cages appearing, like imprisonment motif. The ‘Nazi’ became a very prominent figure and there was kind of scenery which suggested a concentration camp…

BS: People confuse certain things because the images are so powerful. They could interpret it the way they saw it. However his family were totally secular Jewish people. And he was not in touch with his Russian-Jewish roots at all. This was more about the visual aspect and emotions than anything else. He had no interest in politics at all. He purposely kept himself distanced from that.

AK: You had this session when you were dressing up in Tsarevich style and went to the Russian Tea Room. It was a place where people like Capote went to, right?

BS: Everybody went there. Mostly uptown theater people. And in the 80s everyone was dressing up or doing something strange. Anton used to wear flip-flops with this very elaborate, velvet, colorful outfit in the snow. He perfectly fit in, because it was a very colorful crowd. He loved bright colors, especially in the end of his life. His last play was all about the understanding the power of color, how it can affect a person emotionally. In this last piece he was working on there was no figures, just color and light. It was a very healing thing that he was trying. And there was very American, glamorous music from the 50s and 60s. Only three or four people saw it. It was glamorous, beautiful and very lush. He walked away feeling totally invigorated, wonderful. It was completely opposite to the other plays.

Imprint

| Artist | Robert Anton |

| Exhibition | The Theatre of Robert Anton |

| Place / venue | Foksal Gallery Foundation, Warsaw |

| Dates | 21 September – 31 October, 2018 |

| Curated by | Anke Kempkes |

| Website | fgf.com.pl |

| Index | Anke Kempkes Babette Mangold Bette Stoler Foksal Gallery Foundation Jay Sanders Metropolitan Museum of Art Museum of Modern Art Richard Foreman Robert Anton Stuart Sherman Tommy Tune Whitney Museum |