Democracy Anew? is an exhibition which intends to frame ‘thoughts, risks and dreams that define or threaten democracies as we know them today’. The crisis of the democratic paradigm has haunted the West for a long time, voicing anxiety over incompatibility of the existing liberal institutions with changing perceptions of liberty and equality. Yet, recent analyses tend to be oblivious of the extent to which this anxiety pervades the very core of political discourse. The famous work by the triumvirate Crozier-Huntington-Watanuki, The Crisis of Democracy: On the Governability of Democracies, which heralded the critical state as early as 1975 and located the root of the problem in the ‘excess of democracy’, proves the continuity of the fear of primary inefficiency of democratic system in the face of difficulties. On the other hand, contemporary discussions emphasise the recent resurge of nationalisms, anti-multilateral vague of national separateness, and global migration crises. While these arguments are mostly characterised by superficiality and are harnessed into certain political agendas, they have become buzzwords for galvanising Western societies.. The field of deficiency of democratic paradigm proved equally fruitful for art world which explored the diseases of today’s societies in countless exhibition, biennales and festivals. The show at Pinchuk Centre comes as a late-bloomer of this trend.

The field of deficiency of democratic paradigm proved equally fruitful for art world which explored the diseases of today’s societies in countless exhibition, biennales and festivals. The show at Pinchuk Centre comes as a late-bloomer of this trend.

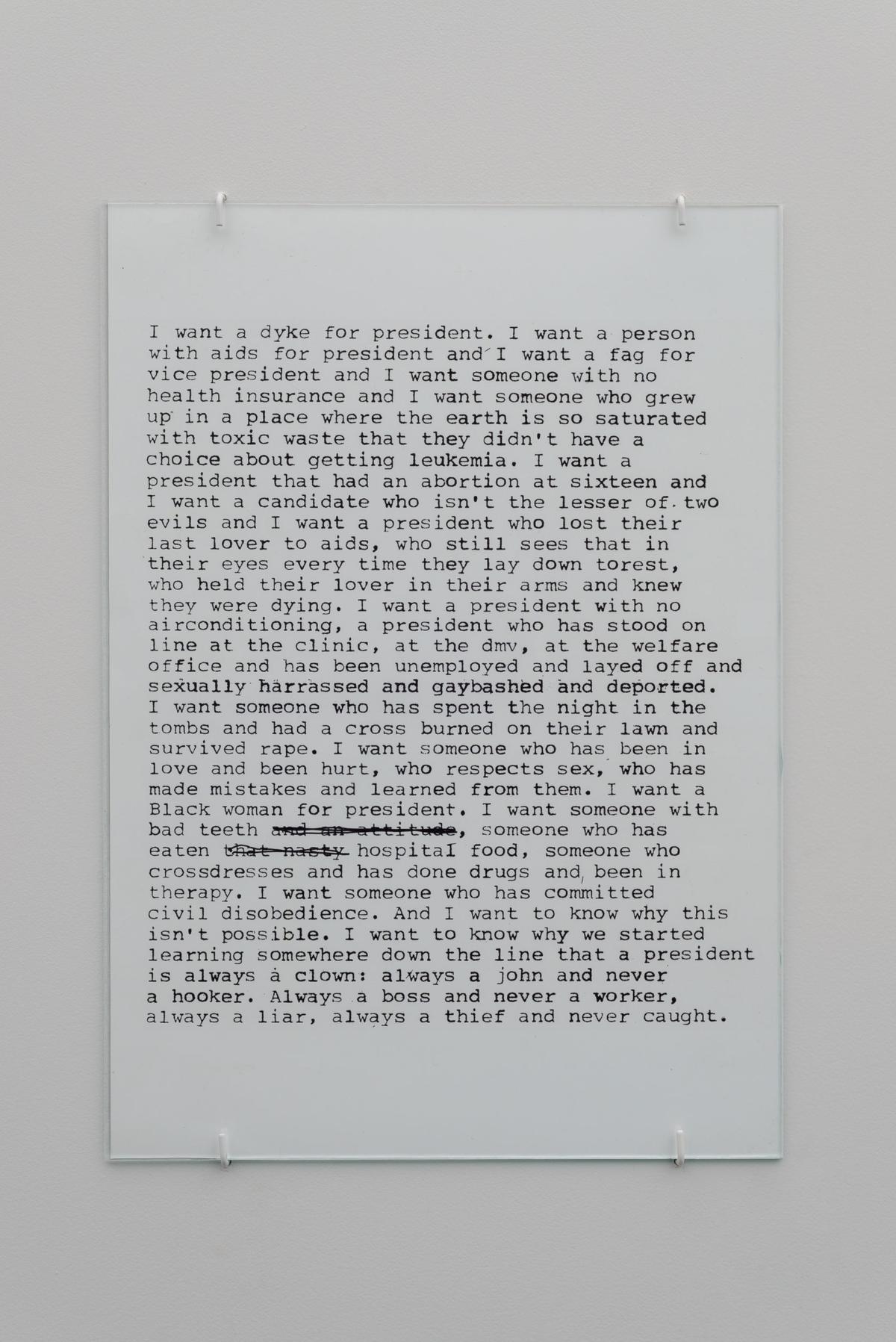

The exhibition starts with strong, resilient words of Zoe Leonard who imagines different political leaders. Leaders, who would know from experience what it is like to be underrepresented and disenfranchised. Leaders, who would be guided by empathy and sense of responsibility and who would know no cynicism. Leonard’s exclamation formally maintains utmost austerity, resembling classic conceptual pieces, with its purely textual character. Leonard starts with the words “I want a dyke for president” and continues to describe what she expects from the political reality. It is not as much a fantasy that is meant to relieve anyone psychologically but rather a foundation for different politics, a call for it. Leonard gives us politics without legislation and regulation, a humane politics, in clear opposition to the coldness and inhumane tone of contemporary political debate.

This high-pitch tone set up by Leonard’s piece unfortunately is not carried forward to the rest of exhibition. The very choice of pieces prevented the show from addressing the problem of contemporary democracies. It almost seems like the key of selecting artist was an art market algorithm of celebratedness, as the exhibition lists by and large the crème de la crème of the art world. There are Takashi Murakami, Damien Hirst, Maurizio Catellan, Luc Tuymans, Francois Alys, Rachel Whiteread, Olafur Eliasson, Goshka Macuga, and many others, equally renown. The issue of consonance between the art appears to be left out of the scope of the curator’s interests. Although the show acknowledges the main threads of the debate on democracy, it addresses none in depth. The existence of these problems is merely signalised. The most painful manifestation of this may be found in the coverage of migration crisis theme. The show presents two works addressing this question – an installation by Sonra Perry, Typhoon coming on and a video by Alys. Perry’s piece covers one of the corridors with ominous projection of purple waves and blow-ups of a painting by Turner, portraying the Zong massacre. The installation shares the title with Turner’s canvas Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying – Typhoon Coming On (1840), which commemorates the mass killing of African people thrown overboard when the slave ship had faced shortages of water. Perry’s ‘Typhoon’ puts the viewer in an uncanny closeness to the painting, whose digitally blown-up surface resembles an organic tissue, wounded skin. The switch to the purple waves draws parallel between now and then, emphasising the topicality of sea as a reflection of human cruelty. Yet all this content remains obscure to the viewer who is not provided with any explanation but rather asked to consume the piece purely visually.

The shows gives its audience an anaesthetic to the democratic crisis: it filters the reality through the sieve of well-established artistic interpretations of the problems and presents it as a consumable commodity.

Alys’s video Don’t Cross the Bridge Before you Get to the River, concerned with migration through the Gibraltar Strait, is similarly decontextualized – the nearest neighbouring piece, photographs by Pascale Martine Tayou, presenting black hands punching through a white paper sheet, touches on a completely different issue. While it is not by definition a bad idea to contrast divergent topics, the problematic aspect of this gesture is the consequent decontextualization of those works. The ghosts haunting democracies are presented as if they were already solved and transfigured into the sublime. Or, to put it another way, the shows gives its audience an anaesthetic to the democratic crisis: it filters the reality through the sieve of well-established artistic interpretations of the problems and presents it as a consumable commodity. This consumable nature appeases the anxiety caused by the disruption of the social order. I am not trying to criticise neither the artworks nor the artists whom I esteem highly. My point is that through inappropriate presentation those works are devalued and emptied out of their original discursive power. Now, given the companionship of the most recognizable (and thus expensive) artworks they gain a tinge of luxury products, and as such, estranged, they appear captured in the between state where its meanings are still readable, yet no more relevant.

The exhibition, unknowingly perhaps, touches upon the relation between politics and aesthetics. Does aesthetization necessarily entail commodification? Can the aesthetic be meaningful (in a political sense)? Whilst the show provides rather disappointing answers, there have been theories proposed which present a different correlation between art and politics. Jacques Ranciere in his Politics of Aesthetics problematised interdependence of both realms, as politics inevitably articulates itself through aesthetics, through the sensible tissue of reality. The aesthetic delineates the imaginable and ensures the appropriate behaviour of the subjects involved in a specific ‘distribution of the sensible’. This theory has twofold implications: art can secure the status quo by repetition of aesthetic formulae, but is equally capable of disrupting the edifice of the sensible, thinkable, sayable, etc, by providing subjects with new forms of collective enunciation. Herein lies the crux of the problem with Democracy Anew?: it does not attempt to look out for new forms to express the faults of nowadays democracies. It rather seeks to squeeze them within frames of already existing aesthetics of art market.

Imprint

| Artist | Francis Alÿs, Allora & Caldzadilla, Maurizio Cattelan, Olafur Eliasson, Damien Hirst, Zoë Leonard, Goshka Macuga, Takashi Murakami, Sondra Perry, Pascale Marthine Tayou, Luc Tuymans, Rachel Whiteread |

| Exhibition | Democracy Anew? |

| Place / venue | PinchukArtCentre, Kyiv |

| Dates | 23 June 2018 – 6 January 2019 |

| Curated by | Björn Geldhof |

| Photos | Maksym Bilousov |

| Website | new.pinchukartcentre.org/en |

| Index | Allora & Caldzadilla Björn Geldhof Damien Hirst Dominika Tylcz Francis Alÿs Goshka Macuga Luc Tuymans Maurizio Cattelan Olafur Eliasson Pascale Marthine Tayou PinchukArtCentre Rachel Whiteread Sondra Perry Takashi Murakami Zoë Leonard |