Let’s start from the end. From grass. Grass is the subject of the series of pictures by Jiří David from his exhibition Jsem tady (I’m Here). Grass is an element, a subject, a phenomenon that Jiří David has found in the course of his artistic research and deep reflection. This search for his self and his own artistic language has its own history. Grass has only recently become a part of it, but this is what we should start with. It should be emphasized right away that the author of this text is deeply convinced that any work of art, realistic or abstract, is a message, a statement. The visitors of an exhibition who are reluctant or unable to read the artist’s message written in the language of painting or sculpture leave the show in the same state they had been before entering it, as if they haven’t even been there.

So, grass. Unlike the Chinese and Japanese art, the Western art provides very few examples of grass becoming a protagonist, as it were, a subject of a distinct reflection, a particular phenomenon of aesthetic knowledge. A few drawings by Leonardo, a picture and several drawings by Van Gogh – that’s about it. Of course, grass is ubiquitous in landscapes, but not as a separate “subject.” However, there is a single and yet absolutely iconic – or even absolute, if one can say so – image of grass, which is a reference point for any reflections on the subject. I mean Dürer’s famous watercolour painting Great Piece of Turf from the Viennese Albertina collection. That depiction of grass has been and will probably remain unrivalled. Unrivalled – because a modern man perceives grass as something devoid of individuality, a mass. Dürer, on the other hand, is on close terms with every blade of grass: he knows each of it by name and sees its unique personality. The piece of turf he draws is on the same level as his eyes. It is not a view from above – that is how we usually see grass if we are not lying on it; it is a view “of two equals.” Moreover, the artist’s consciousness has a deep religious humbleness before any God’s creature, be it alive or not. A modern man has lost this kind of consciousness and perception and is now desperately trying to retrieve it.

‘Wind in the Grasses’, 111×230 cm, oil on canvas, 2019

There is another great image of grass apart from Dürer’s watercolour painting. It is closer to us in time and lies in the realm of poetry rather than visual arts: Walt Whitman’s famous Leaves of Grass. Not much is said about grass itself in this great book, but its presence in the title is important: Whitman was able to express his cosmic worldview and all his human and non-human worlds with the image of grass.

Jiří David has much in common with the American poet. Neither of them has Dürer’s humbleness. They study reality through erotic ecstasy. “I believe in the flesh and the appetites, / Seeing, hearing, feeling, are miracles, and each part and tag of me is a miracle. […] The scent of these arm-pits aroma finer than prayer, / This head more than churches, bibles, and all the creeds.” One can hardly find anything closer to David’s new works than these lines.

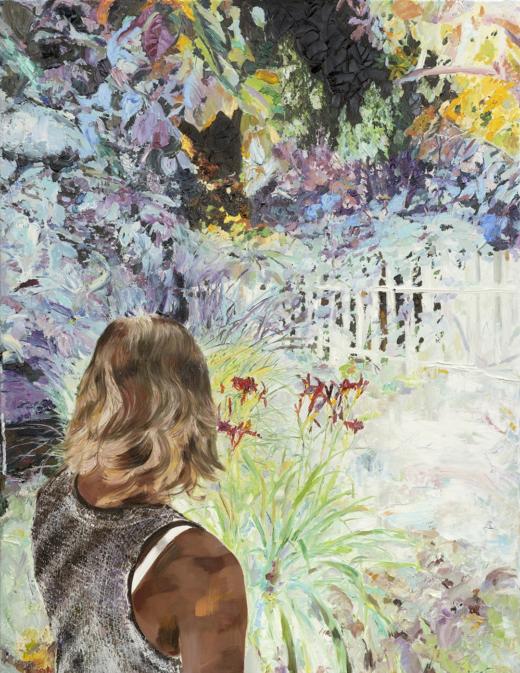

Those who accept Jiří David as well as those who reject him – some with irony, others with tacit awkwardness – always point out his narcissism. Sometimes this narcissism is overt, sometimes it’s covert. However, unlike famous exhibitionists, Jiří David has never exposed himself in public; he is only narcissistic in art, and art allows every possibility it allows. He indeed pictured himself nude in his paintings and photos, but it can be construed in many ways apart from simple self-indulgence. A comparison to Whitman gives a new dimension to his nudity. Particularly when it comes to his self-portraits from behind amid flowers and grass. No one would accuse him of narcissism for that. Here, he is not Narcissus, he is Adam. Adam in Eden before the Fall of man. Or wait! Is it before the Fall? It is Eden, true, but where does the anxiety or even fear come from? Can it be that Adam was expulsed from Eden and then sneaked back in? One of the pictures shows the artist’s wife Zdena (for which read Eve) covered with clothes, so she knows that she was naked, i.e. this is happening after the Fall. One can see a piece of fence in the picture, too. Adam and Eve seem to have climbed over the fence back into Eden and got lost among grass, flowers and sunflecks.

‘Zdena in an inverted garden’, 155×140 cm, oil on canvas, 2019

Speaking of self-portraits from behind, there are three of those in David’s new series. They are all titled A chvěl se jak vánek z nebe (And He Shivered Like Breeze from Heaven), and the difference among them is barely noticeable. A self-portrait from behind is a rare occurrence in the history of painting. One can only recall Vermeer’s The Art of Painting from the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna and, with great reserve, Magritte’s painting of a man who looks somewhat like the author himself: he stands in front of the mirror with has back facing the viewer. A self-portrait from behind, with artist’s face unseen, is always symbolic. It usually proclaims the rejection of one’s ego: Vermeer is looking at the painting, i.e. art, because it is more important for him than his ego; Magritte is facing the mirror, i.e. a mysterious illusion, a magic of endless reflections and patterns; Jiří David is dissolving in the colourful blaze of flowers and grass. Repeating it in three pictures, David insists that a self-portrait from behind, however unusual, is not an accidental artistic gesture for him. I have once been to Maria Yudina’s concert – she played Schubert’s sonatas and repeated some fragments twice, inviting listeners to pay closer attention, because they were important.

But let’s get back to erotic ecstasy. Grass and self-portraits do not exhaust the subjects in the pictures shown at this exhibition – there are female nudes, too. Jiří David’s art is well known for its erotica, which is sometimes so explicit that censorship would have interfered. And again, he is not unlike Walt Whitman about it: “Perfect and clean the genitals previously jetting, and perfect and clean the womb cohering.” But David has walked a long way to reach the sensitive perfection and cleanness of the womb that we can see in Modrý prsten (The Blue Ring), the picture showing a seminude girl in a short speckled jacket. One needs to invent a trick in order to picture the body explicitly and yet devoid of carnality. And David invented it. In Modrý prsten and some other pictures showing himself in the grass (A dešte a slunce mi duhu dluži, And Rain and Sun Owe Me a Rainbow, and other) depict not the body itself, but rather its negative print. This is how he dematerializes physical body. One can say that body in all its explicitness becomes spiritual, and yet surprisingly does not lose its erotic delight, like in Modrý prsten.

Jiří David uses the same device in the three self-portraits mentioned earlier. However, this time it’s more sophisticated: he pictures his own body as a negative while his head remains in our physical world and merges with vegetation. The idea of a split between head or consciousness, which is focused on the sublime and spiritual, and body, which remains in the mortal physical world, is quite common in art and theology. David seems to turn this trivial idea upside down: his body is more spiritual than his consciousness (head). However, something is wrong with this interpretation. If the body is “more spiritual,” why is it so dark? The scenery, all the flowers and grass are full of light, and the artist’s head looks like a part of this landscape, like grass. His head is just as imbued with light, but not the body: it looks like a dark stain, a black hole in this shining space. We are dealing with an ambivalent notion of man, body, and spirit, which is characteristic of modern split consciousness.

A bit more about erotica. One shouldn’t think that erotic delight or erotic ecstasy are only part of the pictures that show a female body. The main source of erotic delight is in painting itself. It is perhaps the first time in David’s artistic life that he so comprehensively and sincerely sees painting – in all its richness, infinite psychedelic range of colour combinations, in all its beauty – as an orgiastic act, as a delight.

In this regard, David’s new works are close to Pierre Bonnard’s ecstatic comprehension of colour. In his book Self-portrait in the Studio, Giorgio Agamben calls Bonnard’s idea of colour a “superior knowledge.”

It is quite interesting to see beauty returning to art after it was pushed out by conceptualism and its numerous ‘post-” iterations, of which Jiří David himself was a part. As David has always been very sensitive to Zeitgeist, there is some hope that his personal revolution is a sign of a general change in art. One could find another proof of that in the unusual Damien Hirst’s project shown at the latest Venice Biennale.

‘Traces of the Night’, 120×220 cm, oil on canvas, 2019

But it’s grass that is important. Grass, by the way, is a slang word for a psychedelic drug. The exciting effect of David’s works is of different nature. It’s not a drug-induced ecstasy and delight, it’s an ecstasy of a teenager lying in the grass and discovering the huge, passionate, and incomprehensible world. And again, Whitman has something to say to David about it:

I loafe and invite my soul,

I lean and loafe at my ease observing a spear of summer grass.

The atmosphere is not a perfume, it has no taste of the distillation, it is odorless,

It is for my mouth forever, I am in love with it,

I will go to the bank by the wood and become undisguised and naked,

I am mad for it to be in contact with me.

I started with the statement that every artist sends a message to viewers in his or her own language, and every painting or drawing is a text. What kind of message does Jiří David send us with his new series? To express with words what he says to us with his art, another mention of Giorgio Agamben might be relevant. Based on the conclusion of his book, Jiří David’s message may read: I put my hopes not on heaven, but on grass. The grass of all kinds, the grass that covers the part of the garden where I have my daily walk. Grass is God. Everyone I love are in grass and in God. For grass, in grass, and as grass have I lived and will go on living.

Prague, 2019

translated from the Russian by Petr Serebrianyi

Imprint

| Artist | Jiří David |

| Exhibition | I'm Here |

| Place / venue | DOX Centre for Contemporary Art, Prague |

| Dates | 17 January – 4 May 2020 |

| Website | www.dox.cz/en |

| Index | DOX Centre for Contemporary Art Jiří David Viktor Pivovarov |