I keep doing the same thing and in a similar way. Neither to prove nor to discover anything. I do it because I wait for something, whose existence I sense, or which exists in my anticipation, to be able to manifest itself. Events last in time, but their image is incapable of conveying something that no longer exists—the identity of the moment that constitutes the image.[1]

In one of the scenes from the film “Vivien’s Garden” directed by Rosalind Nashashibi, the painter Vivien Suter is getting ready to take a nap at her home in Guatemala. Before closing her eyes, she looks up and observes the play of light and shadow over her head—a worker standing on the roof gradually covers the openwork, wicker ceiling structure with banana leaves. The man arranges the plants in a place where a rain and sun protection roofing sheet was broken with such care that one would think he was gently placing a duvet over a slumbering woman. The sun’s rays penetrate freely through individual leaf patches, russet shapes form at the junction of superimposed layers and block the light. The bedroom, first speckled with sunspots, gradually fades into the greenly saturated partial shade. Only then does the artist, soothed by the afternoon performance, close her eyes, and the camera begins to lazily spin around the room in which souvenirs from the past are hung.

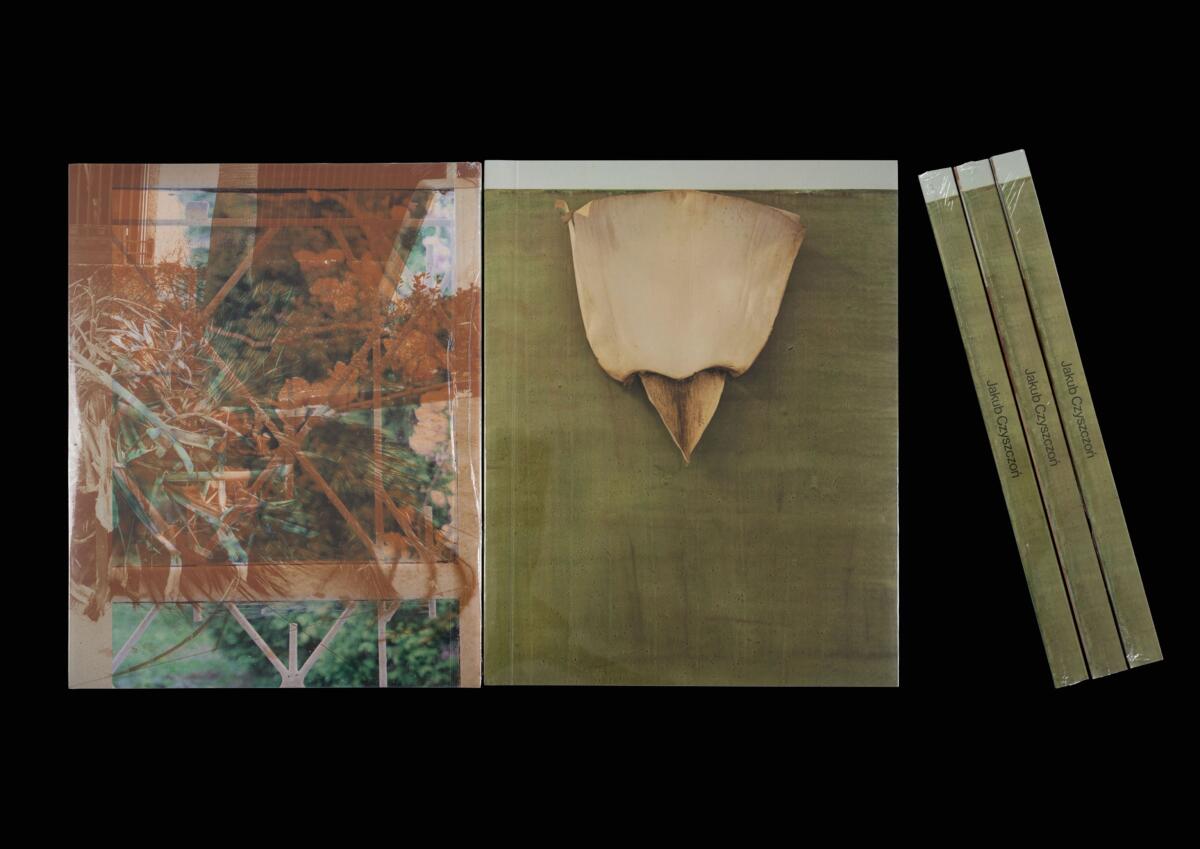

Jakub Czyszczoń, ‘Untitled’, published by STEREO Gallery i ERMES-ERMES, 2020

Nashashibi’s film is a successful documentation of Suter’s work. Even if the camera does not actually focus on the artist’s paintings, it shows us moments impregnated with impressions that could easily turn into traces left on a canvas. In Jakub Czyszczoń’s paintings, one can recognize a similar intensity of sensations not only manifested in the multilayer structure of his works, but also in the selection of materials used. All the processes affecting the shape of the painting—the spontaneity of the painting gesture, an unanticipated chemical reaction, or an experiment provoked by the curiosity the medium evokes—are initiated by an impulse stemming from careful observation of reality. Observation, in turn, is determined by duration, one of the most essential components of Czyszczoń’s creative process, which involves repeatedly returning to the left canvas, just as one returns to a once abandoned thought, directing it subtly towards a slightly different path.

Czyszczoń’s paintings are compositions that go beyond the act of creating temporality, which include or are entangled with other acts—a distant moment in the past that now gains the status of a memory and is transformed into a painting sign, as well as the process of reception, where “(…) the detail appears as an explosive moment, suspending the gaze, which from its wandering passes into stasis or freezes in ecstasy.”[2] The artist’s canvases draw you in, you want to approach them, look closer at the surprising structure, the subsequent layers. In all the elements imprinted in the painting matter, we can detect an original gesture and in it, we look for references to the world, which suspended in abstraction, reaches us in a different, idiosyncratic way determined by the trajectory of our sensitivity. Every eye will choose something different and will recognize other “same old things”, which Ashbery wrote about. In the curious rhythm of the gaze, provoked by Czyszczoń’s structurally vibrating images, it is easy to want more. The received pleasure lies here beyond language—in the migration of the eye between the whole composition and its details, as well as in the deep recognition, paradoxical identification with something that is hard to name.

Jakub Czyszczoń, ‘Untitled’, published by STEREO Gallery i ERMES-ERMES, 2020

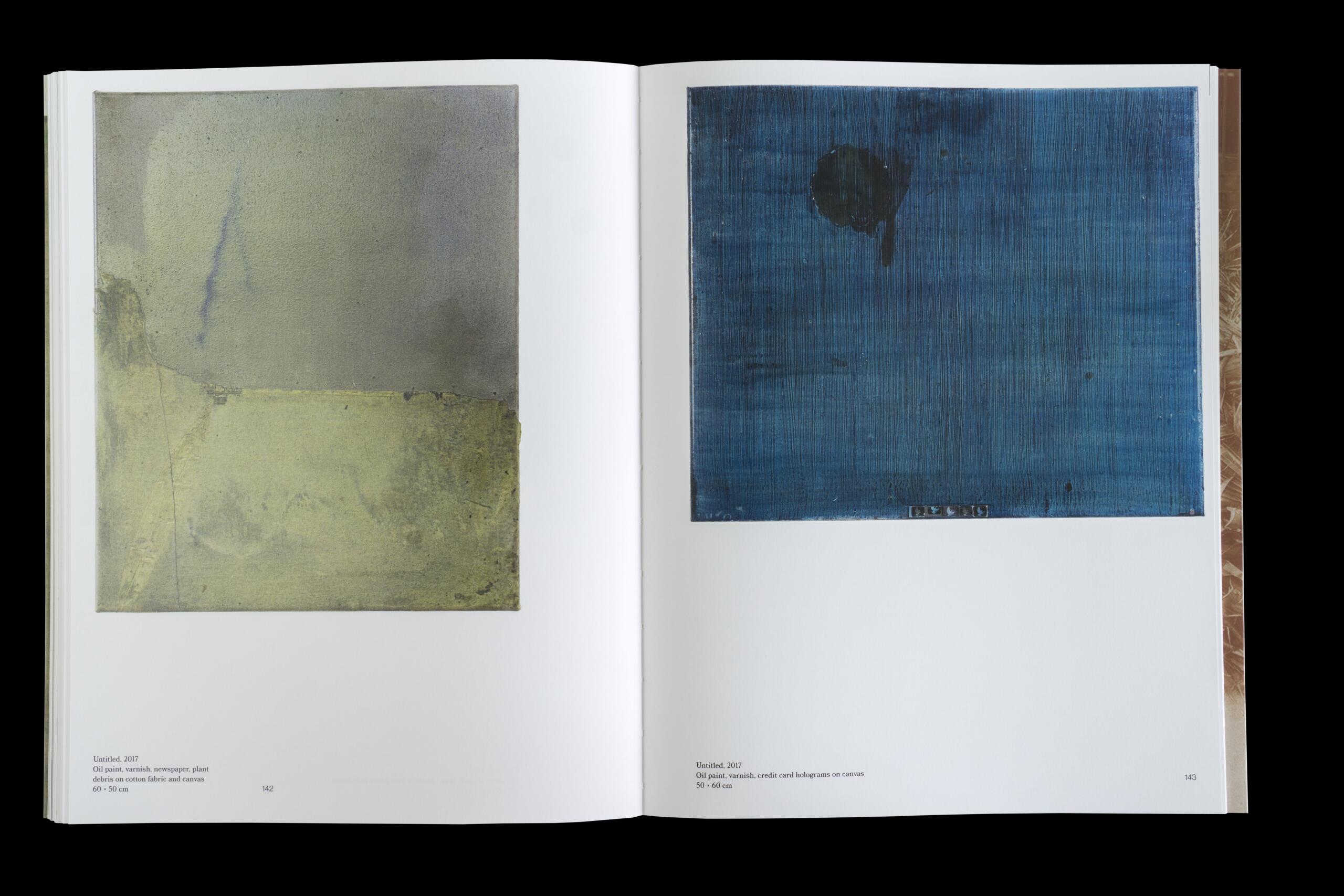

Daniel Arasse aptly characterized the power of detail, which “is more than a part of the painting (…) it is the ‘moment’ of its reception, but could also play such a role in the process of its creation. It is, above all, a painterly <<event>> in the painting.”[3] Detail, as a certain temporality—a moment, a reflection of past experiences, as Arasse suggests further—can only function thanks to an extremely “subjective”, “arbitrary” reception. In Czyszczoń’s “Untitled” paintings, created in 2017-2018, this “event in the painting” is not obvious—a fragment where a layer of a different colour is showing through the paint, a thickening, a texture swirl, an element of organic matter embedded in the varnish. The abstract detail, which is often found on the edge of the canvas, fulfils its poetic function—it takes the viewer beyond the canvas, beyond the studio, and outside the paradigm assigned to the medium.

Czyszczoń is characterized by a specific inquisitiveness—searching for a way to capture the duration of events in their entirety, known only to the observer. However, this inquisitiveness is far from the process of ordering reality, abstracting and naming its elements. Rather, it is based on the tension between knowledge and curiosity, extended during reflection, taking place between noticing something and transforming this observation into a material trace that allows further presumptions but does not close anything. There is no evidence here, only an impression, blurred as a view persistently observed through a curtain. There is also no fever, the kind often associated with curiosity—the next tools are selected according to the thoughts arising in the mind, layers of paint laid harmoniously with the course of the maturing idea.

Jakub Czyszczoń, ‘Untitled’, published by STEREO Gallery i ERMES-ERMES, 2020

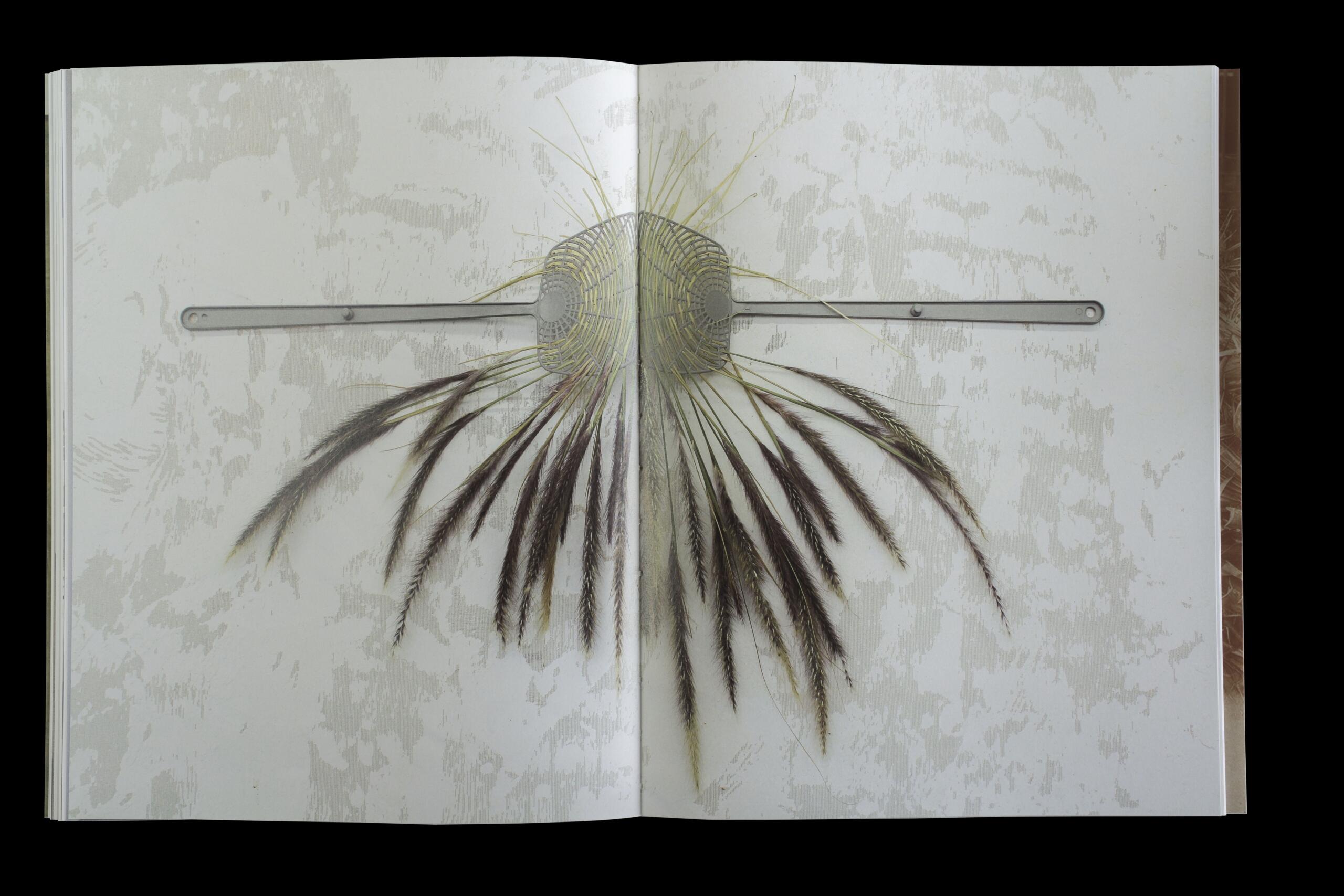

The subversive documentation of the layering process is on the reverse of the paintings, which show the reflection of what was happening on the other side of the canvas. As in a dadaist poem, some elements of the original composition have been cut out here, shuffled and placed on a plane in a new configuration. The original order of thought was disturbed. Substances that played the role of a subtle foundation at first, permeated the foreground. This haphazard effect is a surprise as well as a reminder of what is found deep under thick layers of paint, pigments, varnish, and other matter on the front. Maybe thanks to the verso side, which consists of a wooden loom with embellished pieces of fabric of a different weave, the remains of paints with vivid, unmixed colours and forgotten loose sketches initiating the whole process, Czyszczoń could recreate even some of his accumulated enthusiasms[4], which built the painting in the shape as we know it. The emotions, associated in the painting gesture with matter, however, cannot be meticulously catalogued—they occurred once in a given context. They are reflected on the canvases with a “late echo” and are resounding all the time anew.

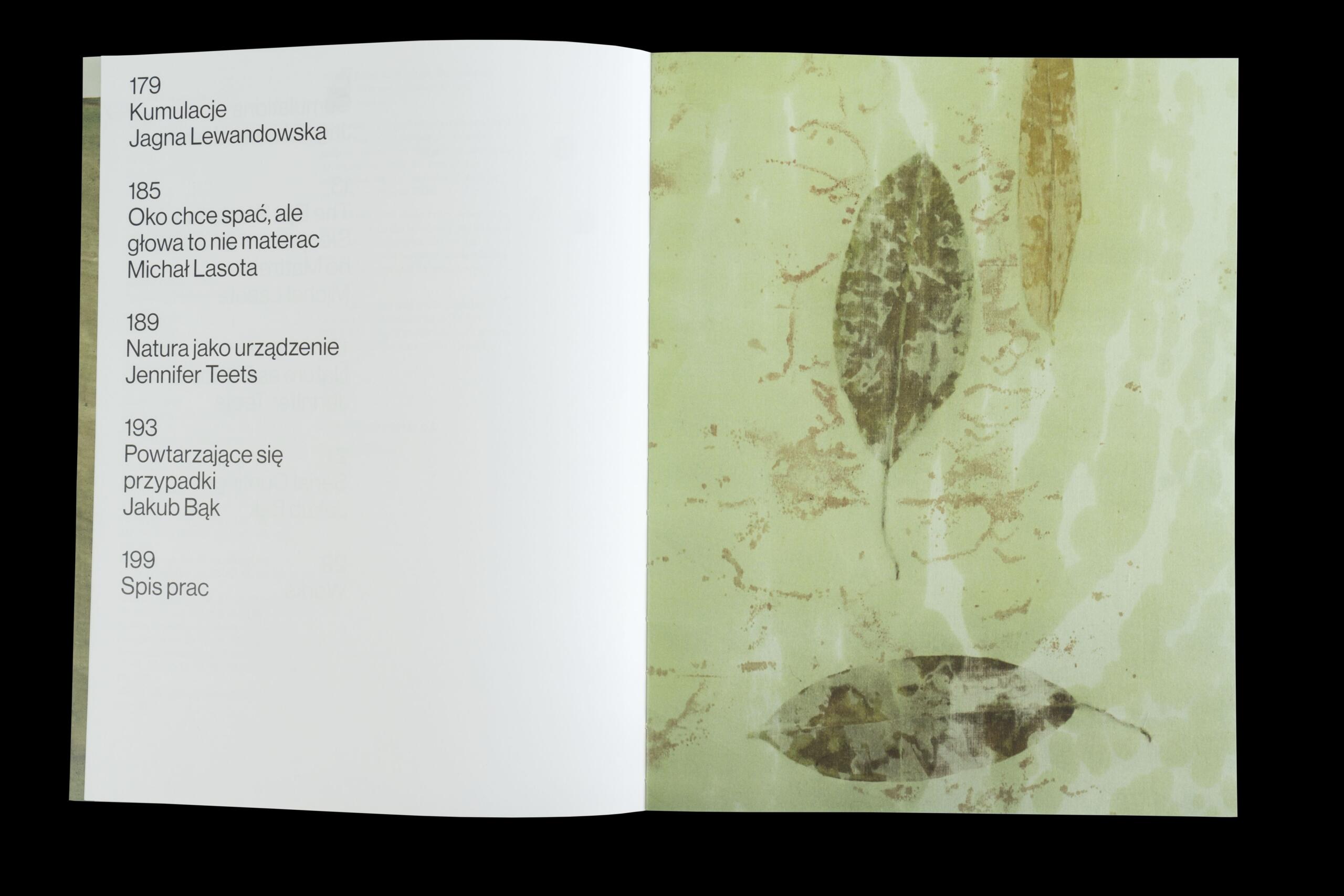

The text was first appeared in the book Untitled by Jakub Czyszczoń (published by STEREO Gallery [Warsaw] and ERMES-ERMES [Rome], 2020), the first monographic catalouge about Czyszczoń’s work, with texts by Jagna Lewandowska, Michał Lasota, Jennifer Teets and Jakub Bąk, designed by Krzysztof Pyda. Publication was supported by the scholarship „Młoda Polska” from The Ministry of Culture and National Heritage of the Republic of Poland.

Jakub Czyszczoń, Noa Glazer, 2017 (from Jakub Czyszczoń, ‘Untitled’, published by STEREO Gallery i ERMES-ERMES, 2020)

[1] Diffused Photography. Polish Inter-Media Photography of the Eighties, Poznań: Galeria BWA Arsenał, Galeria Wielka 19, Salon of the Poznań Photographic Association, Galeria ON, March 1988, s. nn. The text has also been published in the folder accompanying Smoczyński’s exhibition in Foto-Medium-Art. The Secret Performance (przedstawienie ukryte), September-October 1986; as cited in: A. Mazur, Reflections in Time. Mikołaj Smoczyński’s Image Philosophy [in:] What Can an Outsider Tell Us About Reality? Mikołaj Smoczyński, Centre for Contemporary Art Ujazdowski Castle, Art and Present Time Foundation, Warsaw 2013, p. 33.

[2] D. Arasse, Le detail. Pour une histoire rapprochée de la peinture, DodoEditor, Kraków 2013, p. 217.

[3] D. Arasse, Ibid. p. 215.

[4] A place that attracted or accumulated enthusiasm was how Sally Mann defined Cy Twombly’s studio.

Imprint

| Artist | Jakub Czyszczoń |

| Title | Untitled |

| Publisher | Stereo Gallery & ERMES-ERMES |

| Published | 2020, Warsaw, Rome |

| Index | ERMES-ERMES Jagna Lewandowska Jakub Czyszczoń Stereo Gallery |