Joanna Warsza: You once said that it is not easy to imagine the planet as a whole, and if we measure it, we usually start in the West, with Greenwich as point zero. One of my favorite works of yours is Alang Transfer, a collection of artifacts that traveled the world on various vessels, a proposal to rethink political cartography, to create a map without a starting point. Can you talk about it?

Janek Simon: Alang, a beachside village in the state of Gujarat in northwestern India, is the biggest shipbreaking yard in the world. Ships from all over the globe end their lives there, where they are cut into pieces of scrap metal by thousands of workers. What is not metal is removed and sold at a market near the beach. I went there several times to buy different kinds of framed pictures that traveled on those ships. The pictures were predominantly maritime paintings used to decorate cabins, but there were also portraits of different national leaders, maps, and health and safety instructions. I ended up with a collection of more than 150 images coming from more than thirty countries. Before ending up on the market in Alang, those images cruised the seas, going from one port to another for thirty or forty years. When you imagine their trajectories and add them up, you get a quite precise, nonaligned, relational, geometrical construction of the planet. A map that doesn’t have a beginning.

JW: No prime meridian and its anti-meridian forming a ring around the Earth.

Traditional cartography as a Western project of map making requires a starting point, such as a prime meridian. But in Alang Transfer the network does not have a beginning; it only has an end, when all the objects are brought to the beach. It resembles a series of general problems the world is facing nowadays.

I am interested in a possible common denominator between distances on the planet and distance in a cultural sense. What does it mean that something is close or far? Space has a clearly political dimension. There are plenty of metaphors to imagine the world, as a school globe or as an image from orbit, but they are not real in the same way actual distance is.

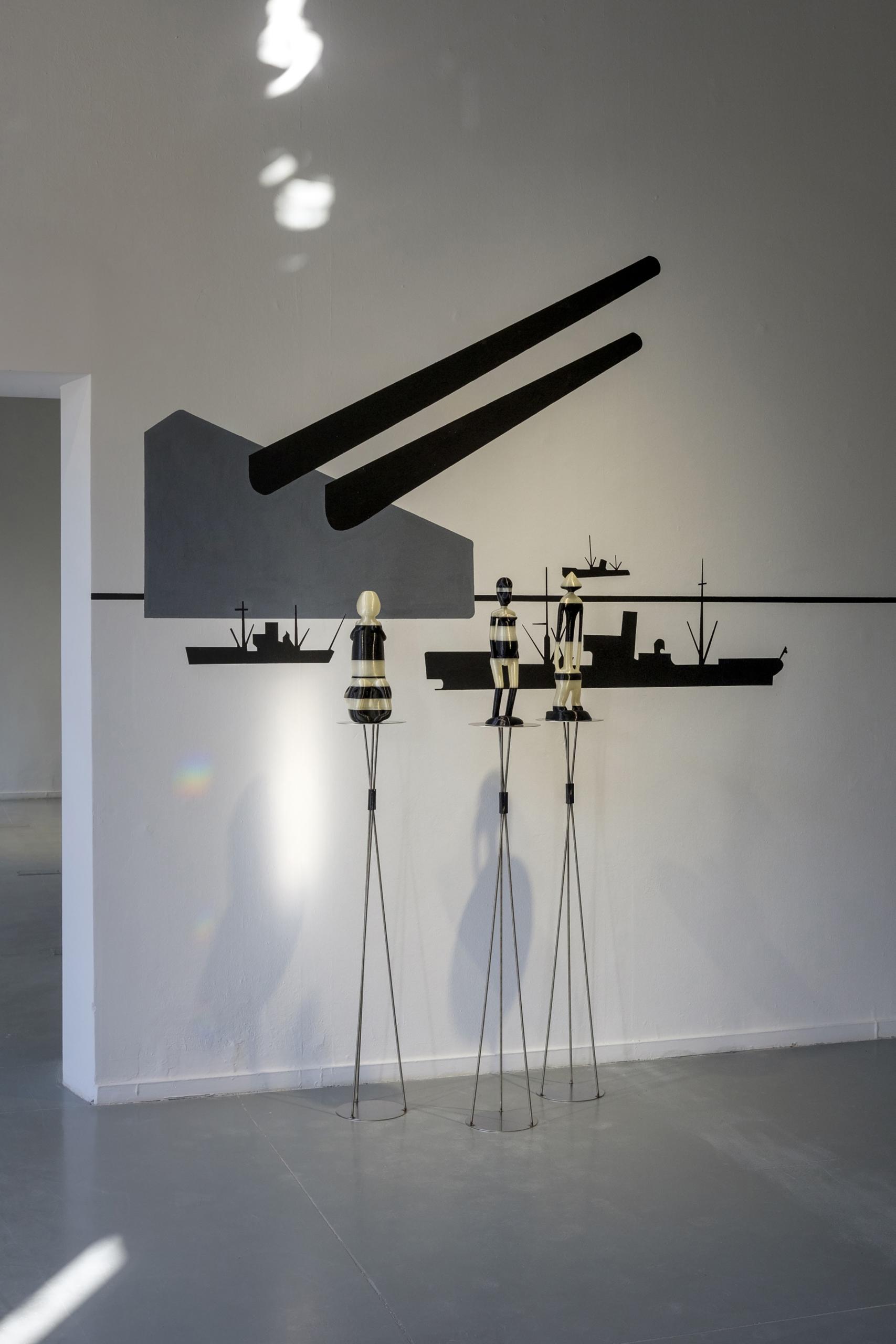

Janek Simon, ‘Synthetic Folklore’, installation view, courtesy of Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art, photo by Bartosz Górka

Ana Teixeira Pinto: How does the concept of cultural geography operate in your work?

I think in at least two ways. First, I am interested in the shape of the space that we live in. You can get from Warsaw to Delhi in ten hours, and it will probably take the same amount of time to go to a village in southeastern Poland by public transport. Space is compressed not only by transportation technologies in different ways, but also by politics and economics. An upper-middle-class Nigerian can get to Europe in seven hours by plane, but the same distance can take seven years for working-class migrants from sub-Saharan Africa to traverse. Trying to imagine the geometry of such a space was always a fascinating task to me—or at least imagining the way you can start thinking about it. How is this space actually constructed? Of course there is the traditional, empirical way called triangulation. You start somewhere and triangulate the space around you, and what you end up with is the cartographic globe. But the problem is that you usually start in the West. I consider this to be one of the main problems of postcolonial theory, and of universality in general. So when you think about how a new cultural universality can be constructed, there are some purely formal, geometric questions behind such a process.

JW: You often speak about the asymmetry of relations between Eastern and Western Europe in the 1980s as an informative aspect of your work. What kind of relation was it? You often mention that you grew up with this feeling of being inferior to the Western world.

It’s very characteristic of Eastern European countries to think of themselves as somewhere in between the West and the East, and depending on the configuration, we might either be privileged or excluded. I was born in 1977 and grew up in the 1980s, and that was a period of humiliation for Poles because of the huge economic crisis. I was lucky, or maybe unlucky, because my aunt emigrated to Denmark in the 1970s. When I visited her in the 1980s, I was able to see the life my cousins had with their mountains of Lego bricks. I developed a feeling that I was born in a wrong and excluded place. Then at some point I decided that I should face it in my work. It’s also difficult, psychologically speaking, because at that time you were an excluded person, an excluded country, and now we are becoming a privileged one—Poland is becoming relatively rich. The question is, what is the moral responsibility related to that? What can we do, and what can’t we do? So you can identify yourself with the position of an underprivileged person, but when you go to India, Asia, Africa, you realize that there is no difference between Western and Eastern Europe.

Janek Simon, ‘Synthetic Folklore’, installation view, courtesy of Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art, photo by Bartosz Górka

JW: There, we’re just European.

Before I saw the world as a dichotomy: the poor, excluded East, and the rich, happy West. This perception only changed when I went to India for the first time in 1998. Later, I spent some time living in South London, and I was fascinated by all the people coming from so many different cultures (often first-generation immigrants) somehow shaping a coherent and functional society. I began to wonder how this objectivity and cohesive societal system, rooted in different beliefs, could be produced. The first and obvious answer to me seemed that exchanges at a basic level allow for these social networks to emerge. We might have completely different worldviews, completely different ethics and politics, but everybody buys a piece of bread for the same ninety pence. I am oversimplifying, but I found this inspiring, and I developed an ongoing interest in small-scale trade, and in the figure of the freelance merchant.

ATP: Adam Smith describes this same scenario. In his version it becomes the foundational myth of capitalism; in yours it retains an anarchic quality.

When the centrally planned economies of the Eastern bloc began to collapse in the late 1970s, their structures were replaced by something that is now called the “suitcase trade” and which was also a form of emancipation. Each Eastern bloc country specialized in a certain range of products, and an official network to distribute them across the region. The system was prone to corruption, and suddenly there were no painkillers in Romania or cosmetics in the GDR. Eventually, an informal network replaced it: tourists were taking things to sell in their suitcases when abroad. You would go from Poland to Romania to sell medicine, and then buy something there to take to East Berlin or Budapest. Gradually, that geography expanded, and suitcase traders went to India or Singapore to buy and sell stuff. The global economy was much less networked at that time, and it was not uncommon to be able to buy something in Poland and sell it in India for ten times the original cost. I found that fascinating and developed a number of projects inspired by these vectors, such as the exhibition “Prince Polonia,” cocurated with Max Cegielski.

JW: You were perhaps the first artist in Poland interested in how postcolonial theory navigated the region, which was both oppressed and oppressor. You traced Poland’s hegemonic aspirations in Africa, linking it to today’s perverse use of postcolonial theory in the nationalist agenda. How did you come to develop an interest in the Polish Maritime and Colonial League?

I came across the Maritime and Colonial League in 2006 while working on a project called Polish Cultural Season in Madagascar. The idea of organizing a fake DIY “official event” in Madagascar rose from my frustration with being part of projects with sole purpose of facilitating meetings among local politicians, but also from a “what-if ” historical scenario. If Poland had succeeded in dominating Madagascar, it would run its own cultural institute there today. I went to Antananarivo carrying a couple of pieces by artist friends in my backpack and ended up renting a small shop on the main street, where I opened a fake Polish Cultural Institute, opposite the French Institute and the Goethe Institute.

Documentation of this action was mixed with archival research on two historical connections between the island and Poland. The first connection is tied to events in the late eighteenth century, when Count Maurice Benyovszky, a traveler and adventurer, became a pre-colonial King of Madagascar for one year, and thus part of the national mythologies of Poland, Hungary, and Slovakia for different reasons. The second Polish foray into Madagascar happened in the 1930s. Poland regained independence after the Treaty of Versailles, and quickly a bevy of imperialistic dreams started to reemerge. Establishing a colony was one of them.

ATP: Could you elaborate on Poland’s plans for Madagascar? I know that the Polish government toyed with the idea of deporting the Jewish population to the island in 1937.

Indeed, Poland wanted to be awarded the island of Madagascar as a token of friendship from France. This was widely known but not seriously discussed. The Maritime and Colonial League was the second-largest nongovernmental organization in prewar Poland. It was established mainly by Polish officers from the Russian navy who, after independence, decided to influence the modernization agenda underway and to promote the notion of opening the nation’s economy (along with its mental geography) to the sea. Poland was never a seafaring nation; the expansion vector pointed east toward the steppes of Ukraine and Russia. So the change they proposed was quite fundamental. They were successful to a certain extent: the construction of the port in Gdynia is considered a key achievement in the modernization of prewar Poland. Soon after, however, megalomaniacal dreams about Poland becoming a colonial empire took root, linking modernism with colonialism. The league lobbied to get the country of Togo (the argument was that as part of what is now Poland was Prussia before World War I, Poland should get a share of Germany’s colonial domains). They started a policy of systematic land acquisitions in Paraná in Brazil. The league also signed a secret agreement with the government of Liberia, which was supposed to bring African soldiers into the Polish army in case of war. Then attempts were made to acquire Madagascar.

At the beginning, in the early 1930s, these colonial ideas were not part of the mainstream political scene. But in the late 1930s, when the economic crisis started to hit, and after the British made immigration to Palestine more difficult, the government began to consider some of these proposals seriously. Political pressure and anti-Semitism were becoming stronger. The idea of channeling emigration from Poland to a single place, where denationalization would happen slower, and the urgency to find an alternative to Palestine, made the government pick up the League’s agenda, and an official expedition was sent to the island in 1937, including members of the Jewish community. It seems that the plan wasn’t really considered hostile, at least by parts of that community. The idea of relocating Jews to Madagascar fluctuated, somewhat in parallel in Germany too. It emerged in the late nineteenth century and climaxed in the Madagascar Plan, a pre-Holocaust Nazi agenda, dropped because of logistical problems. The league also developed a far-reaching educational program. The main magazine, Morze, sold more than 140,000 copies every month. There was even a magazine for children and another one for working-class audiences. Non-Western cultures were obviously presented in very patronizing and derogatory ways.

Even if the League political projects never got any closer to materialization, its ideas became quite influential and, I think, contributed greatly to shaping the extreme racism that quite recently has become more visible in Poland. In the last few years there has been a veritable explosion in racist behavior, and its roots can be found in the League’s activities and ideologies as far back as the 1930s.

ATP: Could you tell us about your encounter with Mr. Seven?

Janek Simon, ‘Synthetic Folklore’, installation view, courtesy of Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art, photo by Bartosz Górka

I met Mr. Seven in Auroville, a utopian settlement on the coast of Tamil Nadu state in India, founded in 1968 by a group of radical refugees from Europe and Indian mystics. Today, it is a mix of radical social experiment and a new-age funfair for rich Western tourists. In its archives I found traces of a discussion from the 1990s on whether the local theater should stage Samuel Beckett and a show of Butoh dance. The highly spiritual residents of Auroville decided there is no place for trauma and no need for culture that represents suffering. It was an interesting question: whether in a realized utopia, there should be no place for pain? Historically, most of Polish culture arose from trauma. This dilemma about avoiding trauma was the source for the Auropol project I realized in 2012 thanks to the support of Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź. I invited six Polish artists to Auroville to put on an exhibition which I curated at a local gallery.

Auroville is a strange and ambiguous place, and apart from recording the artists’ work we also interviewed the inhabitants. In one of the local cafés we met Mr. Seven, who eagerly described his adventures. We taped over five hours of interviews. Seven’s story is a hallucinatory fantasy. He claimed, for example, that he had been hired by Indian intelligence to murder Olof Palme, that he filmed The Birds alongside Hitchcock, that he was present at John F. Kennedy’s assassination, that he had sex with the Queen of England, and that he had restrained Martina Navratilova from committing suicide. In his fantasies, global pop culture mingles with world history, but also with motifs derived from India, such as his joint ventures with the Indian film-industry icon Amitabh Bachchan. At first I treated this material as mostly an anthropological record associated with that place of origin. Then I wondered where the content of these hallucinations was derived from, and how they reflected the current ideology of the place. Later, I began to see in Mr. Seven my own alter ego, dreaming of living in the most incredible and miraculous way, in my case through art.

JW: Another aspect of your work is that you tend to be optimistic about the relationship between human beings and technology. In the early years of your practice you experimented with homemade robotics producing walking bread or a calculator falsifying results. Today you are investigating machine learning and artificial intelligence. You like to ask if algorithms are already better than humans at playing chess or recognizing emotions, or if they could help people to relate to each other? This is one of the driving forces behind your recent work Synthetic Folklore.

Indeed I believe that understanding and using technology has emancipatory potential. You have likely heard about the computer that won at chess against a grandmaster, and also won at Go against the best Go player. You have also probably heard about the controversial algorithm that can recognize your sexual orientation, just based on your pictures. It has a ninety-five percent accuracy rate when it works with photos from Tinder. So I’ve started thinking about whether there is any social good we can use those algorithms for.

Janek Simon, ‘Synthetic Folklore’, installation view, courtesy of Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art, photo by Bartosz Górka

Synthetic Folklore is like Esperanto: it’s about a culture that doesn’t have old or real roots. It is about speculation, about whether an algorithm can suggest a more surprising cultural hybrid than human creativity. I fed geometric textile motifs from all over the world into my computer and “trained” the neural network on this database. The algorithm “learned” to produce new patterns and ornaments. It was a dialogue with my own tastes and preferences, but also with the AI’s. It is a sort of test of how machines could help us to reinvent ourselves. So far I have digitized a collection of Navajo blankets, Polish double-layered weaving, Caucasian carpets, Kente ornaments from Ghana, and folk textiles from Transylvania. This is a sort of speculation, a metaphor, a possible direction for thinking about how to construct a hopeful new commonality algorithmically.

JW: Technology can be biased. It can replicate racist behaviors based on how it was programmed, and other such prejudices.

The biases we observe in certain applications of machine-learning algorithms are a result of existing biases in the datasets used to train these models. Maybe they can be amplified by an algorithm, but never created out of nothing. I imagine that if you write a piece of software that scans the internet looking for pictures of human faces you will end up with a dataset that has a racist bias—more white people than people of color. If you use that data to train, let’s say, a generative adversarial network, the results will be biased too. If you try searching for photos of a “professor” in Google image search, you will get seventeen men and three women on the first page of results—that would resurface as a sexist bias in an algorithm.

ATP: How would you describe the relation of “synthetic folklore” to what is colloquially known as “fakelore,” or to syncretism and cultural appropriation?

Synthetic Folklore is primarily a positive proposition, while the conceptions you mention have various negative connotations. Fakelore probably the least, as it is indeed my inspiration. Traveling around West Africa I realized that the sculptures sold to tourists at the Lekki Market in Lagos or the Accra Art Centre often do not allude to any specific tradition, but are just a mixture of motifs derived from various cultures and places in Africa. A head typical of the sculpture of the Dogons from Mali is combined with a torso from the Kuba Kingdom in the Congo because such hybrids sell better. This inspired me to create the Polyethnic series of sculptures, which are such mixtures—folk art not tied to any one place, but to forms from all over the world.

Syncretism has negative connotations at the aesthetic level, and cultural appropriation at the moral level. They both contain an internal contradiction. Who is to decide where a culture begins and ends and who has the right to make use of its achievements? Labeling of some set of phenomena as a “culture” can also be an essentially a colonialist and violent gesture. As the history of anthropology shows—I have in mind here such phenomena as the pizza effect, or certain traditions of the Maori which turned out to be contrived by European anthropologists—the process by which a culture arises is often complex and full of various types of feedback. One of the most popular dishes in Polish cuisine is pierogi. Similar dishes can be found in, among other places, Ukraine, where they are called pirozhki, or in Georgia khinkali, in Central Asia manty, in China dim sum, and in Japan gyoza. It may be a trivial example, but it demonstrates how hard it is to define a culture as something with hard borders.

Janek Simon, ‘Synthetic Folklore’, installation view, courtesy of Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art, photo by Bartosz Górka

ATP: Cybernetics, a recurring topic in your work, had a rough start in Russia. Not surprisingly, it was briefly outlawed under Stalin, who denounced it as bourgeois pseudoscience. When Claude Shannon’s Mathematical Theory of Communication was first translated into Russian, the editors pored over his writings to purge the text of all “anthropomorphic” terminology, such as the controversial use of the term “entropy.” When it finally took root, cybernetics seems to have had a major cultural influence in the USSR. I was wondering if you’d like to elaborate on its history.

The Soviet Union attempted to use cybernetics to control society and build scientific socialism. Probably the most inspiring for me is the research by Aleksei Gastev on the motions performed by workers on the job. Gastev analyzed in minute detail, for example, the choreography of grinding metal with a file, so that it could later be optimized. The motor dynamics of workers were to be brought to rational perfection. This was not cybernetics, but I think this research shows how they applied this type of knowledge in the Soviet Union. The art world fetishizes Cybersyn, the program created by Stafford Beer at the invitation of Salvador Allende for algorithmic optimization of the Chilean economy. It was interrupted by the Pinochet coup, but I don’t think it had any chance of working. The first wave of cybernetics is more inspiring as a metaphor. Concrete, functioning solutions appeared much later and were based on models entirely different from diagramatic algorithms.

In the 1990s, I was studying cognitive psychology, and hit upon neural networks, an entirely different paradigm, based on the physical structure of the human brain, and more of a heuristic process than an algorithm. I was writing my master’s thesis on the use of neural networks to simulate the impact of stress on the process of solving tasks. At that time there was a lot of enthusiasm surrounding algorithms of this type, but it proved impossible to create something that would really function, and the interest in these models died out.

It is only in recent years, mostly thanks to widely accessible computational power, that machine-learning algorithms could be created to solve practical problems. A breakthrough was AlexNet from 2012, a convolutional neural network that could effectively recognize images—telling cats from dogs for example. Solutions of this type are now used from airport security systems to internet search engines or apps for adding whiskers to faces.

The second groundbreaking result was the generative adversarial network (GAN) system, invented in 2014 by Ian Goodfellow. Networks of this type can be used to create new paintings, and have been employed many times in art. The discussion of general AI is obviously intriguing, but there is a long road ahead to the creation of such a system. What has happened so far is that algorithms can perform a specific, narrowly defined task better than people can. They are better at playing chess, recognizing emotions or sexual orientation in photos, or perhaps driving a car. The question of what else algorithms will be able to do better than people seems to me crucial for understanding what will happen with the world in the near future.

ATP: In the 1960s, two distinct countercultural movements emerged in America: the New Left and the New Communalists. While the New Left sought to effect political change—mostly by marching against the Vietnam War—the New Communalists felt that any engagement with politics, the state, or government as such, was the problem. Between 1965 and 1972, many young, white Americans headed out of the cities and into the rural parts of northern California and built communes. Some had an apocalyptic ethos, worried about impending environmental collapse, and wanted to escape Earth by building new colonies in space. Others had an unyielding belief in technological transcendence and its ability to unify the human race. But their appeals to move beyond politics and history, and build the ultimate version of the good life in outer space or cyberspace, leave unexamined the racial and ideological dimensions which connote this beyond, as well as its peculiar combination of settler colonialism and white flight. I was wondering about your take on digital platforms, robotics, and AI, particularly from a material standpoint, as your work often revolves around the materialities of technology.

You have touched on my sore spot, as my world view has been changing for some time under the influence of what is happening all around. I used to be a proponent of the model of change drawing on anarchism, founded on an extreme mistrust in the state and a belief that small grassroots solutions can be scaled and in some indeterminate future render top-down structures unnecessary. They will fall away like a turtle’s old shell. In the face of the climate catastrophe this model must be revised. Without action at the level of the state, or even higher, we face annihilation. Second, since I was a child I have been a techno-optimist. I received my first computer, a ZX Spectrum, when I was eight. I learned to code when I was ten, and in 1996 I made my first web page. In the 1990s, I was actively involved in the independent techno scene in Kraków, and I still believe that raves and some drugs have political potential. Psychedelics allow people to see the world in a new way and rearrange some of their mental furniture, while empathogens show what incredible emotional closeness with other people we are capable of. The parties themselves offer a rare space in today’s world where anyone can enter without any preconditions—“come as you are.”

In the 1990s, I was very much inspired by Mondo 2000, a cyber/counterculture magazine out of San Francisco edited by the spiritual heirs of Timothy Leary and William Gibson. Technology was presented there as an element of the ideology of the New Communalists. Inventions like the internet, virtual reality, extension of life through supplementation or nanotechnology, today a constitutive element of our reality, were debated back then as a countercultural fantasy. Of course, as you mention, racial, class or in general political themes were not evident, and there were many blind spots. If theories were cited, they were more those of gung-ho media boosters like Marshall McLuhan or Jean Baudrillard. In Mondo 2000: A User’s Guide to the New Edge, an encyclopedia published in 1993 by the editors of the magazine, the entry for “Politics” contains passages from William Burroughs, Frank Zappa, and Jaron Lanier, one of the first theoreticians of virtual reality.

Janek Simon, ‘Synthetic Folklore’, installation view, courtesy of Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art, photo by Bartosz Górka

The first crack in my technological optimism appeared sometime around 2007 when I learned about the economics of electronic waste. In 2008 I traveled to Lagos and saw what happens with the old washing machines, telephones, and PCs disappearing from Europe. What I found at Alaba International, the largest market in Africa, where old electronics from Europe are processed, was frightening. People work on processing old equipment under completely uncontrolled conditions, in toxic fumes from burning heaps of plastic cables or circuit boards boiling in old oil barrels. Recovering raw materials from old equipment is becoming an increasingly important aspect of the economy. This involves for example copper, which is absolutely essential for the production of electronics, and the reserves of which will be depleted in about twenty years. But the working conditions in places like Alaba, or Alogboshie in Ghana, have terrible consequences for the environment and the health of residents. The average life expectancy of inhabitants of the dumps on the outskirts of Accra is twenty-something years.

Another problematic aspect of the material economy of technology is raw materials, particularly the rare-earth metals. A good example is coltan. It is an ore containing two metals very important for the production of electronics: tantalum and niobium. Tantalum is used to make miniature capacitors, which are present in nearly every modern electronic device and are very hard to replace. Some of the world’s largest deposits of coltan are found in the eastern Congo, in territories controlled by private armies. The huge profits from the sale of rare metals have financed the civil war there that has lasted for over a decade. The restricted quantities of some metals are also a factor limiting the development of green energy technologies. The deposits of neodymium and dysprosium, used for the production of wind turbines, or indium, essential for building solar panels, are very limited, and thus a vision in which these technologies entirely replace classic power plants is unrealistic.

The relationship between the production of energy and its environmental cost is very complex, and should not be resolved with one-dimensional buzzwords. I believe the same applies to technology in general, and that’s why it is increasingly hard to formulate criticism of technology using only language.

This text first appeared in Janek Simon. Synthetic Folklore, edited by Joanna Warsza, published by Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art and Sternberg Press, 2020

Imprint

| Author | Joanna Warsza (ed.) |

| Title | Janek Simon. Synthetic Folklore |

| Publisher | Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art and Sternberg Press |

| Published | 2020 Warsaw and Berlin |

| Index | Ana Teixeira Pinto Janek Simon Joanna Warsza Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art |