‘Hyacinth’

In 1982, performance artist Krzysztof Jung was stopped in the middle of a Warsaw street by ZOMO who did not like his ‘exotic’ look and was irritated by his earring – recognised, both by the conservative authorities and a xenophobic society, as a sign of ‘pederasty’. ‘We could pull out your earring and you wouldn’t be able do anything about it,’ said one of the officers.

In November 1985, General Czesław Kiszczak, Minister of Internal Affairs, launched operation ‘Hyacinth’. On November 15, security servicemen entered houses, workplaces, and schools around the country and arrested men they identified as gays. The detainees were outed to family members and co-workers as ‘deviants’. The men were asked about their partners’ names and their sex lives. After violent interrogations, the men were forced to sign the following statement: ‘I have been a homosexual since birth. I have had multiple partners in my life, all of them were adults. I am not interested in minors,’ The interrogations continued until 1988. Security services obtained 11 thousand so called ‘Pink Files’ on gay men. The press was told that ‘Hyacinth’ was supposed to support the gay community endangered by criminals and the AIDS epidemic. Kiszczak’s goal was to out gay men among members of democratic opposition and put them down. Having said that, ‘Hyacinth’ empowered some gay people. For example, Ryszard Kisiel started producing nude photoshoots and began publishing ‘Filo’, ‘probably the first gay zine in Eastern Europe.’

‘Hyacinth’, ‘the Polish Stonewall,’ remains unexplained. There are only a few reports on the interrogated men. The ‘Pink Files’, full of names of both ordinary men and members of the democratic opposition, have been partially destroyed and have been kept secret.

‘Hyacinth’, ‘the Polish Stonewall,’ remains unexplained. There are only a few reports on the interrogated men.

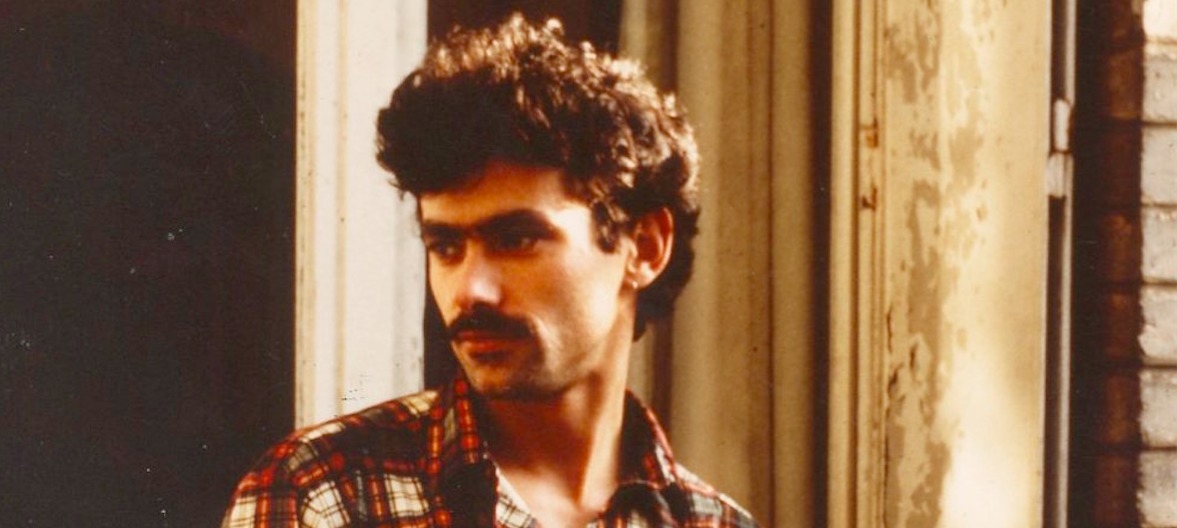

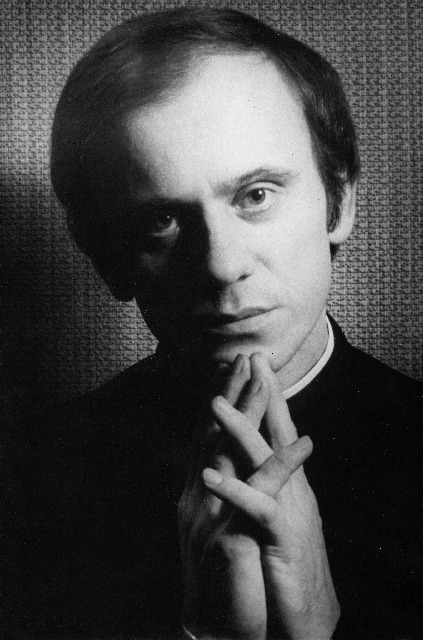

We do not know if there was a ‘Pink File’ on Jung. In 1983, on his way back from a public mass celebrated by Pope John Paul II, Jung was arrested by a secret serviceman, who forced him to admit he was gay. Polish art history recognizes Jung primarily as a performer. His ‘plastic theatre’ spectacles were discussed in two exhibitions which took place after his death in 1998. The more recent one spoke openly about his homosexuality and discussed his performances in the context of gay and queer studies. Jung’s rich photographic archive, a small fraction of which may be accessed by the public and which is held entirely by the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, was just mentioned. His photographic self-portraits were revealed by his close friend, writer Wojciech Karpiński, who decided to publish some of them online after the artist’s death. The portraits are a unique documentation of gay life in 1980s Poland and help build gay agency and gay history, complementing the Western narrative built around the Stonewall riots and the AIDS epidemic. Paweł Leszkowicz writes that the homoeroticism and narcissism of Jung’s art, including his private self-portraits, ‘can be read as a strategy of psychological resistance within a society that places gay men in an abject position.’ In his private self-photographs, Jung documented a masculine image alternative to dissidents’ machismo and countercultural to the official image represented by characterless Communist dignitaries and ordinary workers.

Gay refuge: Jung in Repassage and Maisons-Laffitte

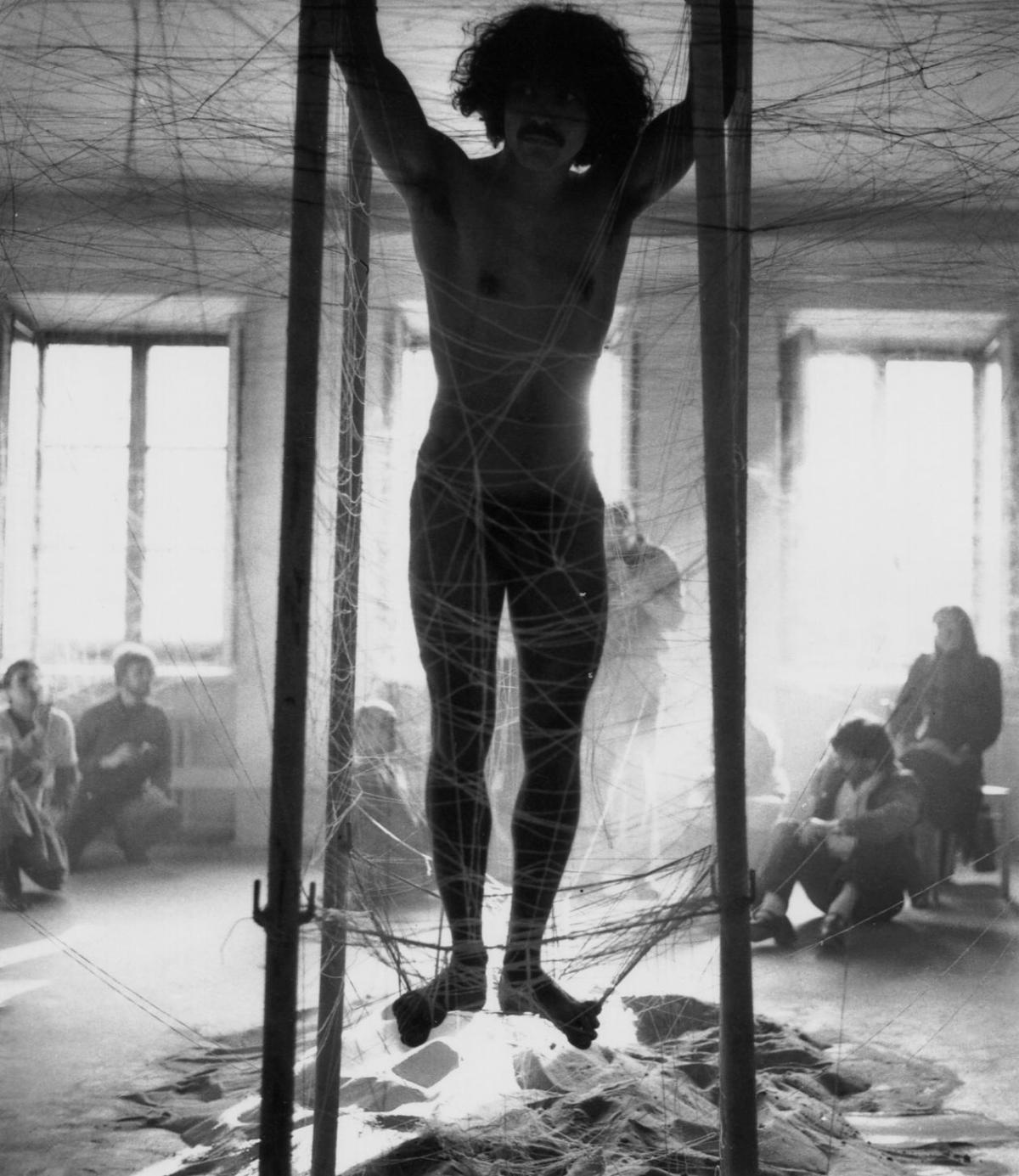

Two centres of Polish counterculture, placed on opposite edges, influenced Jung’s artistic practice and his carefully built self-image. Warsaw’s Galeria Repassage was semi-private space exhibiting works of the most important Polish neo-avant-garde artists of 1970s, among them Jung’s spectacles of ‘plastic theatre’: he usually performed naked, often using threads spun by the show’s participants (friends and lovers), in front of an audience. Actions were usually directed and performed earlier in private. Jung did not allow photographers to be present at the premiere, so the performances were repeated in order to be documented. Jung posed twice – once for the camera and once for the audience. In 1980, while performing Creating Through the Others and the Horizon of Freedom, he resurfaced from a mound of sand and built a spider web of threads, which he pulled from the audiences’ hands. The performance finished when he was suspended in the air held by threads. The photograph, probably taken by Grzegorz Kowalski, had both artistic and pornographic aspects. The artist, a model, stretches his nude body covered by the shadowy camouflage of the threads. Repassage, open to women artists and ‘tolerating’ queerness, was the only place, except his home studio, in which Jung could affirm his firm body publicly and legally.

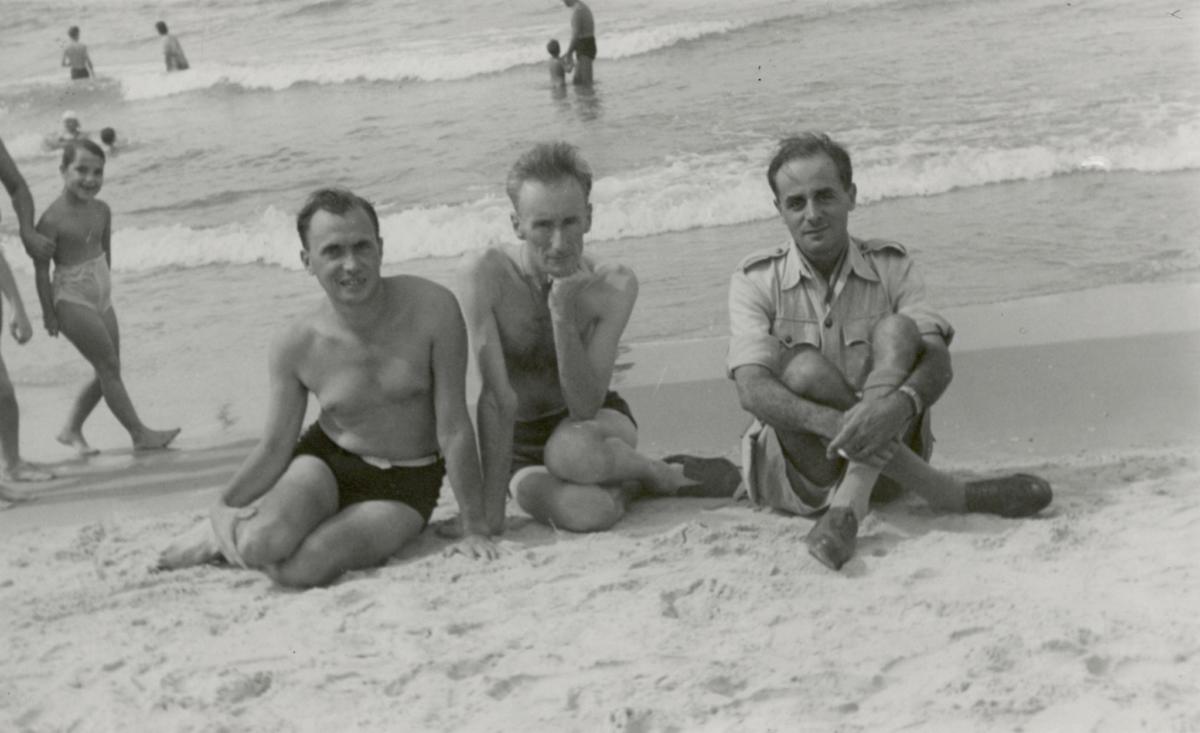

Jung travelled extensively, which was exceptional for an ordinary citizen of Communist Poland. In the 1980s, he began visiting Maisons-Laffitte near Paris, where he met the board of Kultura, the most influential Polish émigré journal run by lifelong friends writer Jerzy Giedroyc and painter Józef Czapski, whom he befriended. His art changed towards ‘conventional artistic practice’ admiring modernist painting and nude male drawings. Many of Jung’s photographic self-portraits were taken as part of the preparatory process for drawings inspired by Czapski’s style. Nevertheless, the photographs are much more valuable both as pieces of art and documents of their time.

Both places of refuge, Repassage and Maisons-Laffitte influenced the different ways in which Jung, surrounded by men who stood out from the image of ordinary Polish men, affirmed his nude body in a documentation of spectacles and studio self- portraits.

Between Dignitaries and Dissidents

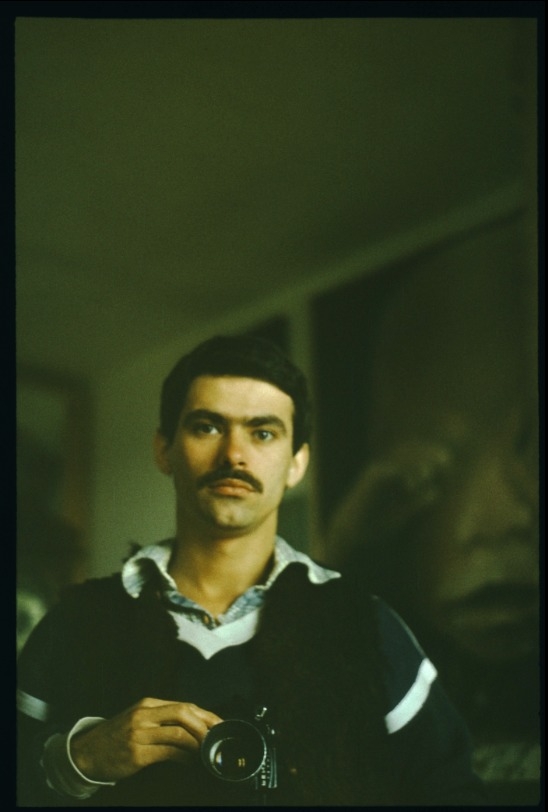

In 1978, Jung moved to his private flat and studio, located in a prefabricated block of flats on the outskirts of Warsaw at ulica Rozłogi. On the photograph, we see Jung posing in front of a mirror with a camera held under his breast at an angle. His focused eyes look towards the mirror while he tries to frame the image. He knows exactly what kind of effect he wants to achieve. His face is illuminated and attracts the attention of the potential viewer. What is unusual, Jung’s hair is short and slick, in contrast to rich dark black curly hair he usually wore. Although in his thirties, Jung is trying to look like a school boy, wearing an American-style oversized jumper with white stripes printed on both shoulders and a loose checked shirt underneath. It is hard to compare his outfit to the Western gay dress code of the 1980s: he is not a clone, nor is he a rockabilly, a post-punk or a skinhead. Jung did not follow Western gay fashion with its return to traditional masculinity. To the gaze of an average young Polish woman, Jung might look Western (American) and a bit feminine. To the average working class man, he looked like a fag. Traditionally, Communist propaganda affiliated Western male fashion with femininity and homosexuality. In the late Polish People’s Republic, gay men could not express their sexuality through their outfits, as restrictive public prudishness was sustained both by the Catholic Church and the Communist authorities. Jung dressed too smart and looked too spruce to go unnoticed on the streets. His smooth, delicate, well-groomed face diverged from the image of a typical Polish man in 1980s, exposing him to violence. He did not fit in in Poland under the economic crisis and Martial Law, with its nationalistic propaganda causing a rise of hatred towards all minorities. Jung’s self-representation also differed from the image of Communist dignitaries of the 1980s. According to Tomasik, these men were asexual to society. For instance, Czesław Kiszczak and Wojciech Jaruzelski (the First Secretary) produced a traditional image of abrasive heterosexual masculinity.

In the late Polish People’s Republic, gay men could not express their sexuality through their outfits, as restrictive public prudishness was sustained both by the Catholic Church and the Communist authorities.

Jung’s image was also far from the one produced by the manly, laid-back, bearded dissidents of the democratic opposition, intellectuals wearing worn-out jeans and crumpled shirts. In Poland, emasculation, gentleness and beauty among men were reserved for priests, particularly Father Jerzy Popiełuszko, a spirited preacher and Solidarity supporter, conquered the imagination of zealous Catholic people. At the same time, Jung’s image differs from that of Poles acknowledged in the West in 1980s and associated with shipyard worker Lech Wałęsa, who authentically personified ordinary working class men in the late Polish People’s Republic.

Unlike the other figures of men in 1980s Poland, Jung practiced ‘radical narcissism’ and ‘exploration of and fixation on the self’, to quote Amelia Jones. Even if of less intellectual volume, his studio photographic self-portrait is reminiscent of Adrian Piper’s ‘private loft performance’ (1971), in which she revealed the presence of the camera and documented her physical and metaphysical changes while fasting and reading Kant. Jung’s performance of a gay man’s private life under late communism was even more secret as he never came out as a gay publicly, while Piper’s work became a statement of the black female intellectual. Behind her, we see a bookshelf, behind him, his painting Narcissus (1976). His home and studio at ulica Rozłogi, an intimate and safe shelter isolated from the militant authorities and opposition machismo, was a realm of freedom in which he could perform his true self- image in the ‘notion of self-affirmation with uncertainty’31 as ‘the relationship between viewer and scene is always one of fracture, partial identification, pleasure and distrust.’32 While Piper was interested in the transformation of her weakened body and mental conditions, Jung registered the ageing process of his face. While Piper’s undressed, Jung dressed up. The photographic self-portraits of two artists living under different conditions are documentations of experiences of ‘the hidden logic of exclusionism’: in Piper’s case caused by gender and her African-American background and in Jung’s by his non-heteronormativity and distinctive facial features, both provoking rejection from a xenophobic society.

An artist and a fag: Jung and Kisiel

Jung sits relaxed and naked in a big armchair covered with brown leather. His body is inclined. His left hand supports his head, his right hand with its cloven fingers lies on his leg. His legs are loosely spread, revealing rich pubic hairs. A golden suntan, smooth lean midsection and slightly marked chest prove that Jung was extremely self- conscious of his body for a Polish man in the 1980s. The shot is cut on the level of his genitals, which remain invisible to the viewer. We must ask if this was an act of self-censorship. Leszkowicz wrote that ‘under the official, populist socialist aesthetics, the full male nude was subject to strict censorship as pornography and the male body, in particular it genitals, were considered ugly and comical.’Jung could be afraid that, if discovered by secret services, the photographs might be treated as pornographic. He did not hesitate to draw erect phalluses, but drawings, unlike photography, were commonly recognized as art. He did not reject full nudity during performances in galleries. We may assume that Jung did not show his phallus intentionally as it constitutes the main subject of homoerotic desire, and sexual pleasure was already suggested by the pose and the nudity itself. The phallus already exists in the gaze of male and gay viewers. Nevertheless, Jung did not like the S/M aesthetic and did not appreciate Robert Mapplethorpe’s self-photographs. For Jung, nudity was not strictly related to sexual pleasure, but also to symbiosis with nature. Of course, much like American artist, Jung used the camera as a tool of self-exploration. Through his self-portraits, he homosexualised Polish masculinity of late Communism. That being said, Jung’s homosexualisation is founded on subtlety and a classical affirmation of the delicate body, which rejects any kind of physical violence present in performance art.

At the time, Ryszard Kisiel, a printmaker and underground gay activist from Gdańsk, represented a different approach towards male homosexual nudity. Shocked, but also empowered by operation ‘Hyacinth’ and his own interrogation, he began publishing ‘Filo’, a gay zine. At the same time, Kisiel began organising photoshoots in his tiny studio flat. These were intended as social events rather than for the production of art. Together with his boyfriend Waldek, Kisiel arranged set designs, disguised and revealed his nude body. His favourite characters to play were ‘harbour hookers’ and women from the margins of society. In one of the photoshoots. he posed dressed up as a prostitute and registered the process of undressing himself on different shots, with the final photograph revealing his nude erect phallus. Recalling Susan Sontag, Kisiel’s camp photoshoots, with their gender-switching, were the triumph of epicene style. At the same time, they produced a fictional, alternative reality, far distant from the rest of Poland, submerged in protests and prayers.

At the time, Ryszard Kisiel, a printmaker and underground gay activist from Gdańsk, represented a different approach towards male homosexual nudity. Shocked, but also empowered by operation ‘Hyacinth’ and his own interrogation, he began publishing ‘Filo’, a gay zine.

There are both similarities and differences in photographic practices of two men, whose self-photographs raised questions about spectacle, spectatorship and desire. In terms of Jung and Kisiel’s practices in late 1980s Poland, the phrase ‘performing for the camera’ can be taken almost literally. Practicing private performances in their homes, they did not have any possibility to share them with the public. The photographs were accessible only to a close circle of friends. In the photographic performative process, Jung and Kisiel shared the aesthetic experiences of photographer and photographed, but also of the viewer. Kisiel’s photographs though, had to leave the safety of the studio and were confronted with the outside world: colour slides could not be developed at home and had to be taken to a commercial studio, where they had certainly been seen by lab technicians. Contrary to Jung, who worked alone, Kisiel involved his boyfriend and friends in the photographic process. Jung took self-photographs to prepare for his drawings. Though they were also distributed as gifts to closest friends, who were also his lovers. For Kisiel, his photoshoots were a form of entertainment which were only recently recognized as having historical and artistic value.

In terms of the self-representation, the difference between Jung and Kisiel’s practices lies in the fact that the first one was not willing to make a joke of his nude body. Presenting his gently toned body in a pose reminiscent of male sitting portraiture (surrounded by late Communist furniture), Jung reproduced the archetypical Western media image of the nude gay male body with its reference to the ideals of classical and antique sculpture. He manuevered between the image of an intellectual (with the bookshelf in the background) and unsatisfied lover ready to fulfil his desires in the next room suggested by an ajar door. Beauty and desire do not seem to be important factors for Kisiel’s work. The happiness expressed on his photographs is reminiscent of the atmosphere of a house party. These differences may lie in the artists’ different class background. Jung, brought up in the prestigious pre-war neighbourhood of Żoliborz, was a son of well-established economists. The Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, where he studied, was one of the most comfortable spaces for all people differing from the homogenous society. Our knowledge of Kisiel’s private life is very limited, but we can assume that he probably led the life of an ordinary citizen of the Polish People’s Republic. He did not travel as extensively as Jung did and he certainly did not know the intellectual and artistic jet-set of the time. The narcissistic Jung, very cautious in regard to what he documented on camera, represented cosmopolitan bourgeois gay culture with its admiration of the perfect body, while Kisiel personified an ordinary gay man who decided to document his youth and happiness without any embarrassment, ignoring all risks.

Despite the differences in their practices, both artists unhinged the politics of the heterosexual white male gaze of the Polish People’s Republic. Their otherness (which may be described as queerness from today’s point of view), expressed in genderising and sexualising their bodies, abstracted and alienated them from the prudish, homophobic reality of 1980s Poland, represented by the Communist government and the Catholic Church, which was growing in strength. When viewed side by side, their photographic self-portraits may be seen as the beginning of a gay semiotic being developed behind the iron curtain.

Conclusion

The narcissistic Jung, very cautious in regard to what he documented on camera, represented cosmopolitan bourgeois gay culture with its admiration of the perfect body, while Kisiel personified an ordinary gay man who decided to document his youth and happiness without any embarrassment, ignoring all risks.

In 2007, two gay activists made a formal request to bring action against General Czesław Kiszczak. The Institute of National Remembrance, which stores the ‘Pink Files’, rejected the request stating that the militia and the secret services were not breaking the law, as the goal of ‘Hyacinth’ was preventing crime and prostitution. In 2010, Euro Pride took place in Warsaw and Ars Homo Erotica, an exhibition curated by Paweł Leszkowicz, opened at the National Museum in Warsaw. Not only conservative parliament members, but the majority of museum employees and curators were against the exhibition and the entire concept of the ‘critical museum’, introduced by former director Piotr Piotrowski, who soon was made to leave his position. Piotrowski stated at the time: ‘The appearance of the male body causes a problem, because of the clearly homophobic orientation of these societies (which is still quite widespread).’ Jung, who stayed in the closet and never wanted to connect his art with his sexual orientation, was represented at the exhibition by his nude drawings and a photograph on which he posed with his lover, referencing Barbara Falander’s sculpture Ganimedes. We could not expect from Jung that he might describe his art as homosexual in the 1990s, because gay relationships at the time were forced to exist without any verbal reassurance.

Jung’s self-portraits might not be recognized as homoerotic without the engagement of scholars who investigate homoeroticism both in artists’ works and biographies. Nevertheless, by affirming his body, practicing narcissism and creating an alternative image of a men in front of the camera, Jung fought the heteronormativity of Polish People’s Republic. His photogprahic practice under the Communist and Catholic Church regimes, has a critical and subversive function and should be recognized as a document of the epoch and implemented into the historical ‘iconosphere’ of 1980s Poland and regarded as proof of resistance in daily life.