Anna Łazar: In the performance For Pawel, you work with Stańczyk, a painting by Jan Matejko, an iconic figure of Polish national painting. Since Matejko depicted significant events from Poland’s history, he is as firmly rooted in Polish culture as Repin and the Peredvizhniki in Russian [culture].

Oleg Kulik: I love the Peredvizhniki. Moreover, I consider myself the last Socialist realist, and the Socrealists follow from the Peredvizhniki. I am the last one, even now that the empire no longer exists.

Is Socrealism important to you as a system of relations?

Of course. As artists, the Socrealists were weak, but their perspective was very contemporary. They were not interested in the existing reality, but in the one they were supposed to see. Whose reality that was is another matter. If the Socrealists had represented their own, that would have been great. But they painted what they were told by phone. It happened that way because people did not believe in social justice. But I do. I believe in it and know what it is. I’ve set up my family and personal life differently.

Perhaps the only place one can establish justice is “around yourself.”

And in many ways I’ve done this, thanks to Socrealism.

Thanks to a declared system of values that never existed?

Not completely never existed. I come from the peasantry; we never would have left the village in other circumstances. But people are rarely independent, they are rarely interested in the construction of life as such. This is where it begins. Say, the national question. We live in this question, we have to react somehow. At this point I have no idea what a “nation” is. It’s some kind of vulgar thing. I have a very sensitive reflection on it. I’ve been a Buddhist, a Tibetan, a Mongol. I wanted to become anyone and everyone. With one exception—I did not want to become a Pole. There are preconceptions that Poles are cruel, they once enslaved the Ukrainians. It was a shock to discover, in Tibet, that in a previous life I was a Pole. When Arti Grabowski invited me [to the International Meeting of Performers] last year, I knew that I had to give Lenin back. Even dead. Lenin came to be only because of Poles — Dzerzhinsky, among others.

In Poland, its dealings with the Russian empire and how it underwent modernization within the empire remain hidden. This is a very strange complex. An empire is also built by those it subjugates. To be at once a victim and bear the shadow of the empire is very difficult.

But what can you do? It’s impossible to escape the cycle of victim–assailant without religion. I was born not in the Ukraine or in Ukraine, and not in Russia. I was born in the Soviet Union. This is very important. Both my father and my mother would say: You were born in the Soviet Union. I learned of a higher power only from my grandfather. But my father was a Communist, he worked in the ideological department; and I sensed a higher power. I was severely punished for this, but I still managed to lead many people to the church and to baptize them in the 1980s and ‘90s. I was a fanatic. The priests at that time were astounding people with principles. My greatest trauma came from what became of them [later]. It’s clear that the bureaucrats, the army, the KGB would become corrupt. But the priests… The moment that crumbled, for me, everything else became possible. I went down on all fours, I stopped being human. The national was religious. Everything became vulgar. In Russia, people began asking me, are you Ukrainian? I said, no. I’m the devil. And if I were Ukrainian, then so what? Does that make me a nationalist? I responded to their question with another. Do you believe in God? I do. Will you show me your cock? That’s indecent. And I would say, my question is far less indecent than yours. You are asking about far more intimate things.

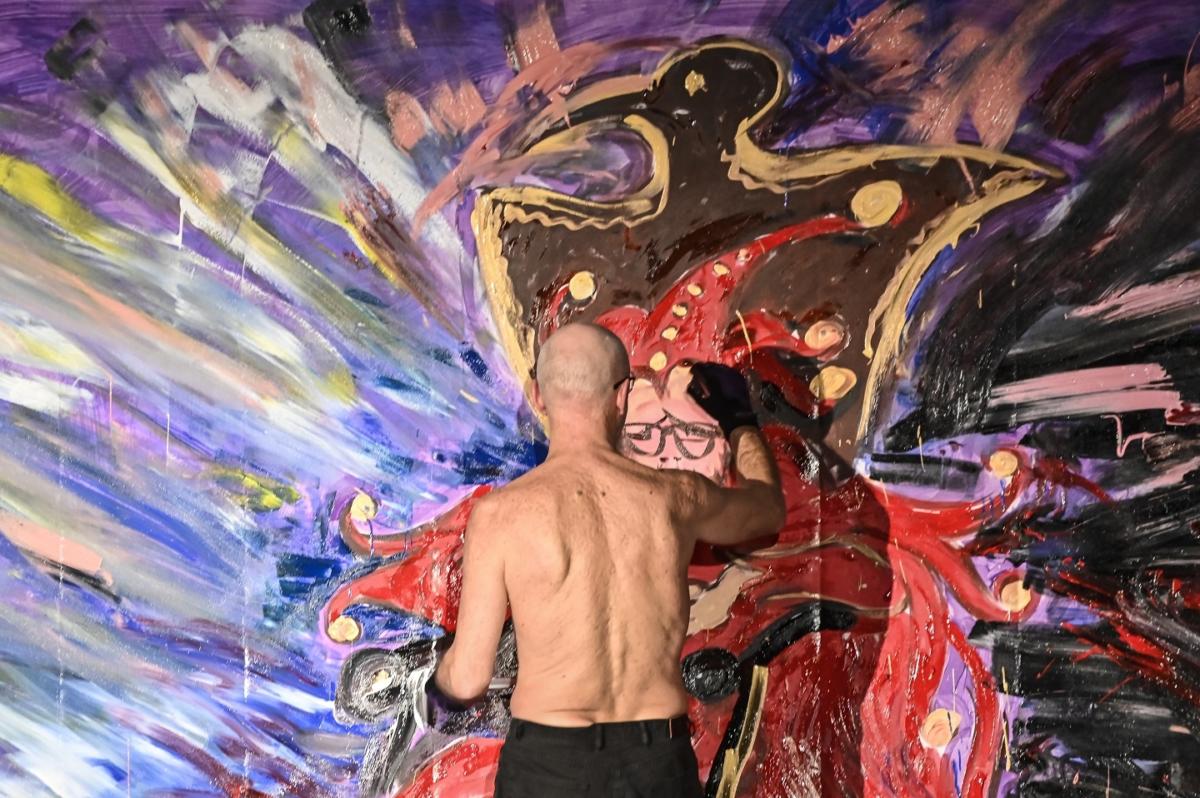

Your painting performance was expressive but pretty calm. You revealed yourself as Stanczyk. I thought you would put yourself in his place, but you depicted Adamowicz.

It was me. I was into the idea of “Adamowicz as me. I am Adamowicz.” It’s one line of jesters, murdered by society.

Adamowicz was the mayor of Gdansk—a person in power and the victim of a hate campaign, who was literally murdered. And you portray him as a jester.

The system is suspicious of those who are in the system, as well as those who oppose it. I am sure that Adamowicz was not liked by conservatives, by those who are against gays, liberalism, contemporary art.

There is a symbolic universe in which all the narratives are set, only the figures change. But you’ve changed the subject.

Nowadays everything is movable, and narratives should change. But the attitude of those in power to humor doesn’t change. Contemporary society is commercialized, the play of images means nothing. I thought everyone had forgotten Adamowicz. It’s important to me that he is remembered. Now let’s put everything in its place. This is a fascist, this is a conservative, this is a political victim. He’s ours. This one is not a clown, not a victim, not ours. And where is the position of strength, confidence?

In this painting the position of strength is specific. Matejko creates a high sort of narrative on the theme of national myths. Stanczyk is a topos, or subject in [our] culture that is treated in various ways in different periods. And you offer a surprising interpretation.

An incorrect one. You have to consider it in its entirety. I was referring mostly to art. First I proposed that I wanted to make a painting. Arti [Grabowski —ed.] said, Well… a painting. Do something radical. Well—I have an old idea — Lenin in Poland. I wanted to extend my hand and say, we can’t lay Lenin to rest, but let’s finally bury him in Poland. I am Lenin. He has to be taken from Sopot to Krakow and laid to rest in the church where I was the priest in a previous life, as I learned in Tibet. One of my reincarnations buries another reincarnation. I am Lenin. I trimmed my beard like Lenin’s and dyed my hair red. I am Lenin. And I will bury him as a Polish priest—a Catholic—since the Orthodox Communists can’t manage it. And the image of the clown from the film Joker, which I also refer to, is a powerful diagnosis of society. Let’s see — Greta Thunberg with Asperger’s, autistic people don’t like people. They are asocial and can act absolutely independently. The little girl Thunberg is much more frightening than Lenin. Others can be bought, you can negotiate, but none of that with her. I love Greta Thunberg, but not Lenin. In Russia it’s the opposite. They can’t even bury him. They understand that he is a villain, a monster. But he’s our monster. Here Matejko acted as a precursor to the Joker. I depicted the Jester who alone suffers for the entire empire. The other fools feast, while he thinks. He is a high Joker. Working out the pain of the world alone.

This gesture of destroying symbolic stagnation reveals a lot—the hierarchy of the high, among other things. But here it is also evident that this is a subtle gesture of remembering. We’ve forgotten how strange it is that Lenin lies dead in the center of Moscow.

Yes, he’s dead. But also not dead. The Mummification Institute is still working, as is Lenin’s Brain Institute; his skin is rejuvenated. Possibly, with nanotechnology Lenin will wake up. Building an empire around an open grave really is bizarre. A person who did not like people—fine if he were some kind of work-loving sovereign. No. A monster sleeps there. As I was packing for Poland, I had a feeling that I would be killed during the journey from Sopot to Krakow, where I was supposed to get up and say the last word. Lenin ought to say his last words. Bid farewell. Apologize for all that Communism. Here lies Vladimir Lenin. The earth will not accept him. In Tibet, it is believed that if a body is preserved, the soul cannot get out. DNA, that it could join with, is a living thing, and it is working in Lenin. Lenin must be liberated. And then Russia will be liberated. It’s a completely magical act. To break the spell over Russia with Poland’s help. And Adamowicz played a very important role here, and some devil killed him, which prevented the act from being completed. Of course it would have been cooler if I in the image of Lenin had been killed. Pawel Adamowicz saved me.

Imprint

| Artist | Oleg Kulik |

| Exhibition | 7 ½ International Meeting of Performers “Mish Mash” |

| Place / venue | PGS Sopot |

| Dates | 17-19.01.2020 |

| Curated by | Arti Grabowski |

| Index | Anna Łazar Arti Grabowski Jan Matejko Lenin Oleg Kulik Paweł Adamowicz PGS Gallery Stańczyk |