Karolina Plinta: In April this year, the exhibition Action Lublin! opened in the Labirynt Gallery. This is the third edition of the larger project. Could you explain some of its concepts?

Waldemar Tatarczuk: This project is concerned with presentating performance art and the history of performance art in Lublin. Mainly, what happened in the Labirynt Gallery.

Why are you focusing on the Labirynt Gallery? What is so specific about this institution?

Labirynt was established in 1969 on the initiative of the artists living in Lublin. Labirynt was supposed to be a gallery working in opposition to the local BWA, but it did so in a subtle way. A radical change in the program took place in 1974 when Andrzej Mroczek became the head of the gallery. Mroczek graduated from the Art History program at the Catholic University of Lublin, which at that time was a very interesting educational institution. Jacek Woźniakowski lectured there at that time – he was a lecturer who opened the students’ eyes to contemporary art. Here, later representatives of the neo-avant-garde formation – Wiesław Borowski, Anka Ptaszkowska, Włodzimierz Borowski, Jerzy Ludwiński and Urszula Czartoryska – studied. They were all pupils of Woźniakowski. Under his influence, the Castle group was also created. During his studies Mroczek could observe these new artistic phenomena.

Andrzej Mroczek decided to show what was valid in art in the Labirynt Gallery. He started with performance. Most of the artists from the neo-avant-garde generation came to the gallery – Krzysztof Zarębski, Jerzy Bereś, Zbigniew Warpechowski, Teresa Murak, and Józef Robakowski. The gallery featured video art and feminist artists: Natalia LL, Ewa Partum, and VALIE EXPORT. The exhibition of performance work culminated in 1978 when the first performance festival in Poland, “Performance and Body”, took place in the Labirynt Gallery. The festival was attended by such artists as Tibor Hajas, Rasa Todosijevic, and the KwieKulik.

How was it possible for a gallery with such a profile to operate, especially in those days?

I do not know, maybe there was a good climate for it in the town (laughs). The status of the Labirynt gallery was different from the BWA (Bureau of Art Exhibitions) galleries, which was supposed to exhibit more mainstream or classical exhibitions. Although in Lublin, the situation was not that bad – the BWA management often made its spaces available for the Labirynt Gallery.

Thanks to that, an important exhibition, which showed artists connected with the Labyrinth, was organized in 1976 there. There was an exhibition by Christian Boltanski, Anette Messanger, an action by the Academy of Movement… so BWA was not that bad. Maybe it was possible thanks to the contribution of the Zamek Group and Jerzy Ludwiński. And in 1981, Mroczek became the director of the BWA, which was a precedent for the entire country.

Andrzej Mroczek decided to show what was valid in art in the Labirynt Gallery. He started with performance. Most of the artists from the neo-avant-garde generation came to the gallery.

You started to run the gallery after Andrzej Mroczek. Somehow, you continued his policy, and the results of this could be seen in such projects as Action Lublin!

We started the cycle – along with Paulina Kempisty, who was a co-curator of the 1st and 2nd part of the project – from the exhibition of artists associated with Lublin: Janusz Bałdyga, Ewa Zarzycka, Włodzimierz Borowski, Teresa Murak and Zdzisław Kwiatkowski. We wanted to show their most important work done in the Labirynt Gallery. The exhibition was supplemented by performances by young artists from Lublin, presented during the opening.

In the second edition of Action Lublin! young artists played a bigger role.

Eight artists presented the second exhibition: the classics of Polish performance art who did their work in Lublin. I decided to confront them with the works of young artists and artists, so I invited the Studio of Spatial Activities (pl. Pracownia Działań Przestrzennych, PDP), led by Mirosław Bałka at the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts. The exhibition also took into account the historical activities of the PDP.

This is not the first time you have invited PDP to the Labirynt Gallery. Where does this cooperation come from?

For me, this is an interesting workshop that is run by a sculptor, not a performance artist. Nevertheless, the performance is a dominant strategy in PDP. Bałka has a different approach to performance than other artists who run performance studios, who deal with it themselves, such as Janusz Bałdyga, Artur Tajber or Ewa Zarzycka.

He avoids using the term performance and prefers to talk about a “performative act”. It is interesting that his students have a non-mimetic approach to the art of previous generations – they do not try to imitate older artists, and as for artists, they do not duplicate well-known gestures anymore. They are looking for a new form of performance.

At the exhibition in the Labirynt gallery, apart from archival activities of the PDP, new works by students who were currently studying at the studio were shown. Bałka suggested to his students that they should reference classical art within the exhibition (these references were: Maria Pinińska-Bereś, Jerzy Bereś, Zbigniew Warpechowski, KwieKulik, Józef Robakowski, Akademia Ruchu, Jan Świdziński, Ewa Partum). And they actually referred to them, but not directly.

The third edition of Action Lublin! focuses on art in public space.

In the latest installment of the series, I decided to go beyond the medium of performance and expand the exhibition with other activities – those relating to the urban space of Lublin.

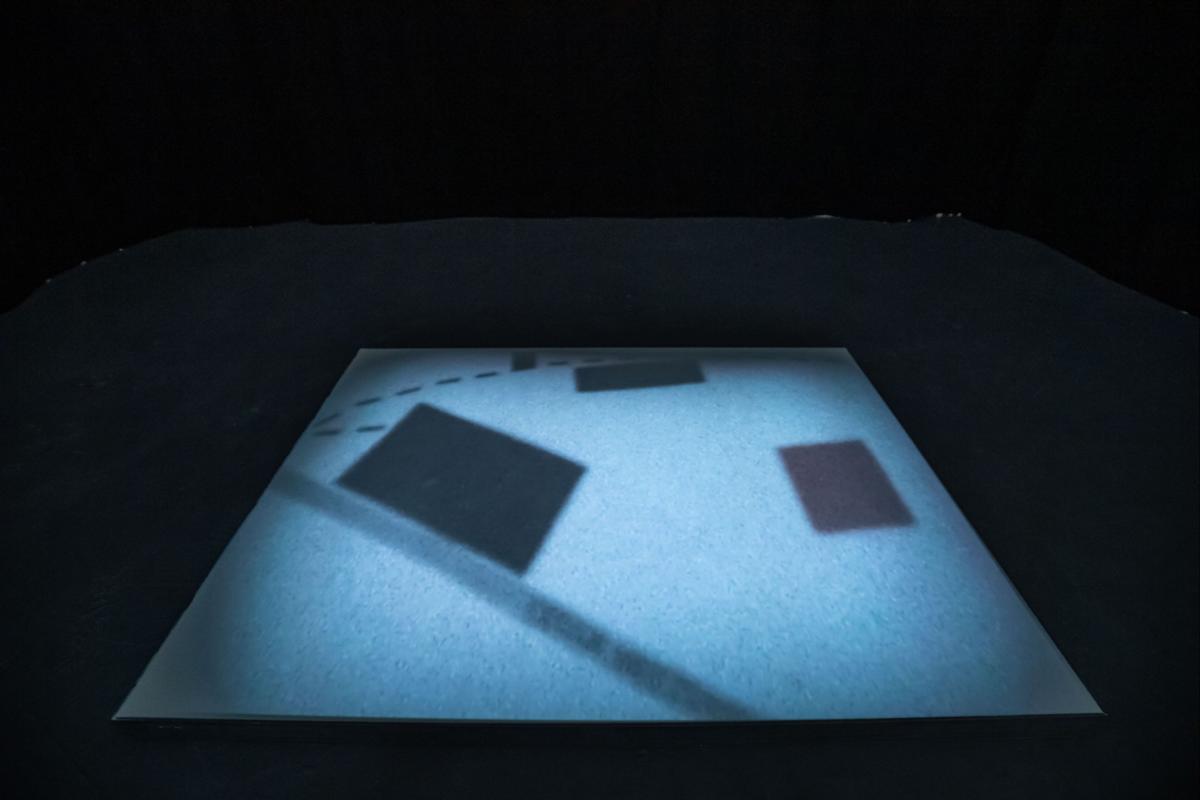

The starting point of this exhibition is the work of Mirosław Bałka, who depicted the map of war in Lublin, including the places where Jews were killed. Why is this work so important?

Originally this exhibition was prepared for the Petach Tikva museum in Israel. I decided to make an exhibition about Lublin for this museum. Thinking about works in public space, I decided to make a narrative about the city based on work done in public space, specifically at the Museum of the Concentration Camp at Majdanek. This map, which we can see in Bałka’s work, is the city plan of Lublin, which used to be in the museum. So it is a job related to a specific place in the city and at the same time showing the city.

With Majdanek alone, which is the most famous Lublin building, the city has a huge problem because nobody knows how to use this place. It is a difficult memory, which people don’t know what do with, so it’s left alone.

Bałka’s work is devoted to the pogroms of Jews in Lublin, but in fact the exhibition itself is not focused on this topic.

In this exhibition, I was most interested in how the city’s map changes. The map, filmed by Bałka, depicts the old Lublin – after the war, the city radically changed its face, especially around the castle and the bus station. Before the war, it was a Jewish quarter with a completely different network of streets.

The Germans began to demolish the district, and the Poles completed its destruction during the celebrations that marked the decade of the People’s State. Currently there is architecture from the 1950s. On the other hand, the district where the Labirynt Gallery is located was in the past the area of the Jewish town of Wieniawa. Only the pre-war town hall survived from that time.

In the place where the cemetery was, the Germans built a stadium, which is still standing today. So at the exhibition, different maps and meanings overlap. With Majdanek alone, which is the most famous Lublin building, the city has a huge problem because nobody knows how to use this place. It is a difficult memory, which people don’t know what do with, so it’s left alone. In a sense, Adina Bar-On’s performance, which took place in the Old Town, which was inhabited until the Second World War by Jews, also referred to this past.

Majdanek is not the only area that shows the problematic nature of Lublin’s heritage. At the exhibition, for example, we will see the work of Cezary Klimaszewski, who registered the demolition of the Youth Culture Center at the Juliusz Słowacki’s housing estate, designed by Zofia and Oskar Hansen. On the site of MDK in 2010 stood a pseudo-Gothic church. The film Open Form as a passe-partout of patriarchy, made by Cezary Klimaszewski, Tomasz Kozak and Tomasz Malec is devoted to this architectural disaster.

Juliusz Słowacki’s housing estate is an example of the biggest realization of Oscar and Zofia Hansen’s idea of the Open Form. One of the goals of this housing estate was to create zones that served various purposes. Therefore, a residential and recreational zone was designed to be located inside the housing estate while the commercial or garage zone was left outside. The school, health center and kindergarten were also located outside the residential area. The estate is, or rather was, a huge green area. On the outskirts of the estate is an amphitheater, surrounded by greenery, which as one can see in the Hansens’ conceptions, was to be a monument in honor to honor the poet Julisz Słowacki. It was mean to be a public facility instead of statue. In the center of the estate was a cultural center, conceived as a meeting place. Cars were banned from entering.

The situation on the estate changed after 1989.

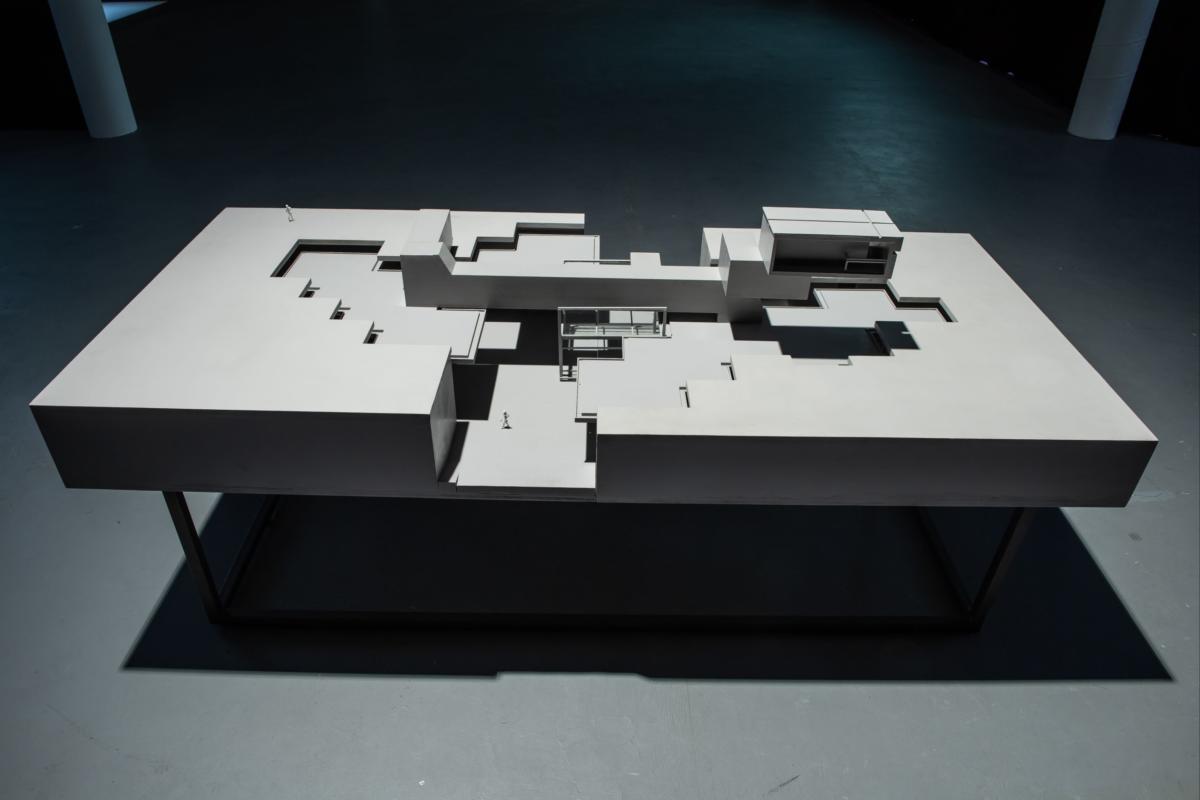

WT: In 1999, the church, on the wave of universal reprivatization, received a plot in the very center of the housing estate and decided to build a temple there. The priest also put a huge parking lot in this area. Of course, nobody in the estate asked if they needed a new church. The estate conceded to the construction reluctantly, and it is possible that this is why the first parish priest of this institution committed suicide. Referring back to the title of work, Cezary Klimaszewski, Tomasz Kozak and Tomasz Malec talk about the Church as a patriarchal form, which in a sense diverges a lot from the Hansens’ aspiration for an open form. The film is presented alongside an architectural mock-up of the an underground church on the plan of the destroyed cultural center. Let’s say that this is a proposed wish for a future building, which should stand instead of a hideous church.

The exhibition also includes works that are fantasies about the past. Like the work of Robert Kuśmirowski, who dressed up as a laborer from the times of the Polish People’s Republic and for a month dug a mysterious pit in Lublin.

This action took place as part of the first edition of the Open City festival, which he was the curator of. It was a heroic feat. The artist single handedly dug a spiral down in the earth for a month and poured a spiral top. He did this to simulate the old construction site, left over from the “previous era”. This, of course, aroused the interest of passers-by who often asked him about the purpose of his digging. Kuśmirowski talked to everybody, so hype about the building started circulating around the city.

Juliusz Słowacki’s housing estate is an example of the biggest realization of Oscar and Zofia Hansen’s idea of the Open Form. One of the goals of this housing estate was to create zones that served various purposes.

The work of the duo Nezaket Ekici & Shahar Markus where they took on the role of clueless tourists also seems quite humorous.

Their action consisted of camping in the center of Lublin in the middle of winter. The artists were dressed in swimsuits, lighting a barbecue and smothering themselves with oil for sunbathing, while lying on a square covered with snow. Nonetheless, the absurd, though poetic action was Cezary Bodzanowski’s action of titled Release. During it, the artist walked around the city and persuaded people to free themselves by distributing advertising leaflets. In the final rendition of the work, Bodzianowski threw all the leaflets into the basket.

To this edition of Action Lublin! you also invited young artists.

Arutiun Sargsyan, the Nice Words duo (Barbara Gryka and Agata Rucińska) and the works of Joanna Pietrowicz, Berenika Pyza, Olena Siyatovskaya and Olga Skliarska represent the younger generation of artists. The work of the Nice Words duo is an installation made of post cards. These post cards have been filled out by passers-by that the artists met at the station in Lublin and at the market in Petach Tikva. They asked them to write a few words about the city. This project was naive in the assumptions it made: on postcards from Lublin you could find quite infantile slogans. Interestingly, the passers-by from Petach Tikva did not have such positive feelings about the city, so the artist, faithful to the duos name, Nice Words, they excluded some “unpleasant” comments. Arutiuna Sargsyan’s minimalist form of action referred to the refugee crisis, which began in 2015.

The four remaining artists are students of the Performance Art Workshop run by Janusz Bałdyga at the University of Arts in Poznań. Their actions were taken either just before or on the day of the vernissage. At the exhibition we showed raw material from their actions.

The works shown at the Action Lublin! exhibition make visible the various faces of Lublin. To sum up these faces, how would you define Lublin as a city?

Simply put, Lublin is a diverse city. The exhibition features works on the history of the city, its architecture, stories about contemporary media culture, dramas from the past and contemporary times. Artists are different and pay attention to various aspects. Some use elements found in the city space, others treat the city as a background for their work.

Will there be another edition of Action Lublin!?

Considering how much previous editions have been focused on local artists, I am thinking about an international exhibition that shows the relationship between various artistic scenes. Many foreign artists have come to the Labirynt Gallery since its beginning. This, however, is not concrete. Basically, the purpose of Action Lublin! is showing the history of performance that happened in this city. A story where everybody basically knew what happened, but hardly anyone knows what that exactly looked like.