To give our readers a broader view on the Moldovan art scene: how did it look before the pandemic? Are there strong institutions, public or private, or is it more organized from below, by the artists and cultural workers themselves?

The Moldovan art scene consists of several organizations created by artists and cultural workers. An alternative art scene was created in the 90s with the support of the Soros Foundation, just as it happened throughout the socialist bloc. As an alternative to official Soviet art, it was powerful and timely, but these initiatives did not develop into any state or private structures. The state still annually supports the unions, which were created in Soviet times, and contemporary art is supported mainly by foreign grants. Of course, all this does not strengthen the sector, but rather weakens it.

Despite the fact that people (including artists) leave for a better life in the West, there are enough human resources in the country to develop contemporary art. In 2020, a coalition was formed to start lobbying for the interests of the independent cultural sector of Moldova, and to start a constructive dialogue with government agencies. There are already positive changes occurring, this year the Ministry of Culture will finance two projects related to contemporary art: Alternative Cultural Spaces Week in June 2022 (an initiative of the Young Artists Association Oberliht) and the exhibition The portrait of Mark Verlan at KSAK Contemporary Art Center.

How has the pandemic affected the art community in Moldova?

Chisinau was not active even before the pandemic. Events related to contemporary art are not often held in our capital. Therefore, there were no special changes at first glance. We watched remotely the cancellations of various major exhibitions around the world, while in Moldova there was practically nothing to cancel. Basically, only exhibitions by the Union of Artists of Moldova and the National Museum of Fine Art are held on a regular basis, so of course all of this stopped during the quarantine.

As in the rest of the world at that time, we all moved online, spending time on digital platforms. And it no longer mattered whether you lived in a European cultural center and had access to events or lived in a provincial town. And artists at the periphery began to question this typical aspiration of being in the center. On the other hand, our art activities abroad also stopped at that time and only now are gradually recovering.

During the quarantine period, there was enough time to engage in long-term planning among all cultural players. We came to the conclusion that it is time to change something deeply in the local context, and to consolidate. It became clear that action must be taken from a structural level and individual initiatives will not change the situation.

Certainly, one of the reactions to the pandemic was the project Pandemic, Artist and Ecology. Please tell me about the idea for it and your role – I believe you are the initiator of it, but you also took part in the exhibitions as an artist, is that right?

Pandemic, Artist and Ecology, was a participatory project that arose during the first lockdown from March–May 2020, which culminated with the exhibition Breathing with One Voice. The borders were closed, it was forbidden to walk and to meet with friends and we needed to minimize our contact with relatives, especially the elderly. Police cars would drive through the courtyards and terrify the entire district with a piercing roar “Do not leave your houses.”

When internet-based social networks became the only way to be in contact with people, I began following my friends and fellow artists, checking how they were surviving this time. For me, some of them seemed to be heroes of that period, like the anthropologist Lilia Nenescu. She and her husband tried to clarify the situation of homeless people, to see how they were coping with the ongoing situation. The most vulnerable categories of citizens during the two-month lockdown were indeed the homeless, who were deprived of the opportunity to hide in their homes and be safe. Lilia recorded the stories of these people in writing, how they ended up on the street and how secure they felt during the quarantine period, and tried to help them solve a number of problems.

Another interesting person is Transnistrian photographer Anna Galatonova who, during the lockdown in Tiraspol, posted on Instagram not only her photography but also ads for dogs from shelters looking for homes. I was inspired by the civil position of these people and wondered what I could do for the art community. What further increased my interest was a thought that everyone had their own experience and that it was worth summarizing our general feelings from this time. It became clear to me that such stories need to be identified and recorded.

I wanted to unite Moldovan artists scattered around the world through a project without borders. If earlier it seemed that we are all different, since we live in different conditions and contexts, then this new challenge made everyone equal in their rights or in the absence of rights, and created a space for discussion and exchange of experiences. It also became a great opportunity to consolidate Moldovan cultural workers and to introduce the public to artists from near and far, who are very rarely exhibited in Chisinau.

The final point, which gave me courage and even more motivation in the development of this project, was an interview in the magazine “Scena 9” with Raluca Voinea, a curator and art critic based in Bucharest. She spoke about the consequences of lockdown and the need to return to the material world, to the community, in order to touch and breathe together, but at the same time preserve this experience of isolation in order to give yourself the space to not suffocate each other. This is where the working title for this project came from.

In the exhibition text we can read about general issues like democracy, human rights, and ecology, but also very personal things, like the fears or hopes of artists who need to face a new reality. How are those different problems and questions made visible in the artworks presented in the exhibition?

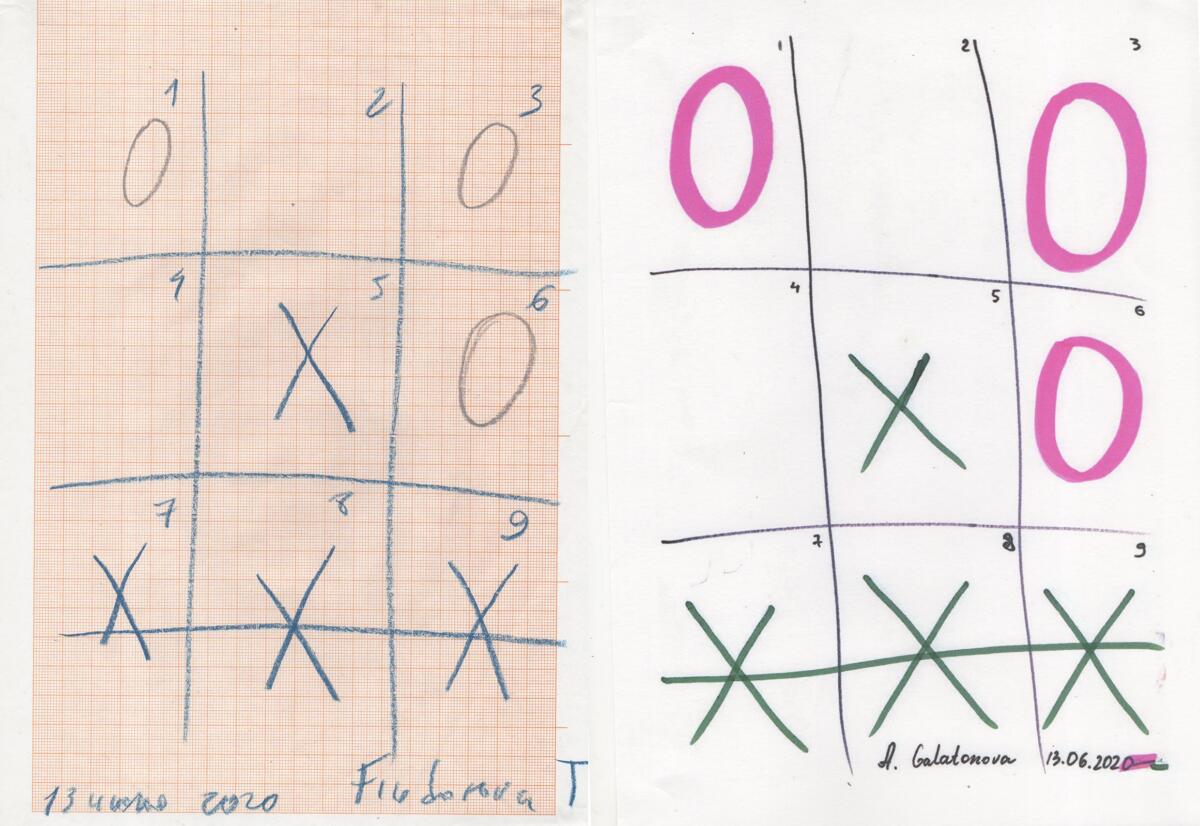

All these topics were raised and discussed between the participants. Inspired by Lilia Nenescu and Anna Galatonova, I invited them to play tic-tac-toe, a game which everyone is familiar with from childhood regardless of where they’re from or their country of residence. I started using it as an art project in 2017. I played it with Moldovan artists like Pavel Braila, Ghenadie Popescu, Marik Virlan, Valentina Rusu-Ciobanu, as well as with artists and cultural workers from other countries: Andrei Nacu (Romania), Natalia Vatsadze (Georgia), Cristi Nae (Romania), Brandon LaBelle (Germany-USA). Sometimes the game turned into a verbal dialogue and revealed a certain topic. That is, the game was a kind of pretext for further discussion, which could last more than one month or even a year. Before the pandemic, the game always took place in direct physical contact. Since the borders between Moldova and Transnistria were closed during the lockdown, I invited Anna and Lilia to play tic-tac-toe remotely. The results of the game and subsequent publications were posted on Art Ploshadka, a website I created in 2009 as a cultural platform for arts workers and artists to share events and thoughts.

All these materials were presented in the exhibition. The correspondence with Anna Galatonova lasted no more than one month, the game and dialogue with Lilia Nenescu, about post-capitalism and democracy, lasted for about a year and covered as well different topics and time frames of the pandemic. It was published in mid-October 2021. The presentation of these two games and publications became the central link between the exhibition and the entire project.

Along with the game, I invited my friends who are artists and activists to share their experiences of surviving the lockdown period on Art Ploshadka since not everyone uses social networks and posts their stories. For example, we published two interviews with environmentalists from Moldova and Transnistria. Ecologists shared their opinions on the current environmental situation in our region, on the problems associated with climate change, on the pollution of the waters of the Dniester River, and on the education of citizens’ environmental consciousness.

Ecologist Ilya Trombitsky also suggested paying attention to alternative energy sources like thermal accumulators, which are inexpensive and are able to turn solar energy into warm water even in the cold season. To do this you need to make a small investment, often there are very inexpensive methods, and you can design everything with your own hands. It seems to me that this is a rather relevant topic for which artists could develop modern designs using inexpensive materials.

We also had a Zoom meeting where we shared our thoughts about the present and the future. We discussed how the pandemic affected creativity and participation in exhibitions, travel restrictions, and the ability to financially support ourselves during this difficult time; about teaching online, what are the pros and cons of this format. And of course, we touched upon the topic of isolation and the marginal status of the Moldovan artist. Subsequently, online communication has also grown into an exhibition format.

Could you tell me more about the artworks presented in the show?

A number of works in the exhibition are critical of the capitalist system, which – during the pandemic – revealed a number of problems, such as in the fields of healthcare and media, or in the building of a democratic society.

Alexandru Raevschi, an artist who lives in Germany, searches for meaning and significance in the concept of “democracy” in the contemporary world. In the performance Fishing, the artist is depicted slowly eating a cake with the inscription “democracy”. The process turned out to be difficult, but nevertheless, the author was able to symbolically reveal the contradictions between contemporary liberal democracy and global capitalism. Democracy today is losing its original meaning with the rise of nationalism and global elites who pursue an economic policy that is oriented not to the interests of the majority, but to the minority, turning democracy into a plutocracy.

Photographer Ramin Mazur reflects on the work of the Fourth Estate, that is, the media in general, and especially during the pandemic. He draws a parallel between the virulence of the virus and the dissemination of information in the media about the spread of the virus. His video work Corona Scope explores the “infodemic” nature of the spread of the virus, which made it difficult to understand what was happening and how to get out of the situation. The artist Igor Shcherbina also experienced difficulties in communication. As he describes his work A Book without Text, “The time of the pandemic blew up the brain: I look like a cartoon character, where the media was captured by aliens, and the exchange of information turned into a quest ‘believe it or not’. I seem to be lost in reality. Perhaps I stopped understanding what communication is…”

The exhibition featured a series of photographs about the Dniester river in Dubossary, taken by environmental activist and journalist Elena Stepanova from Transnistria. In her interview she described the ecological situation of the Dniester and the current state of drinking water in our region. She is concerned that the extraction of sand and gravel from the Dniester has recently intensified, which can lead to environmental problems, since sand and gravel are natural water filters.

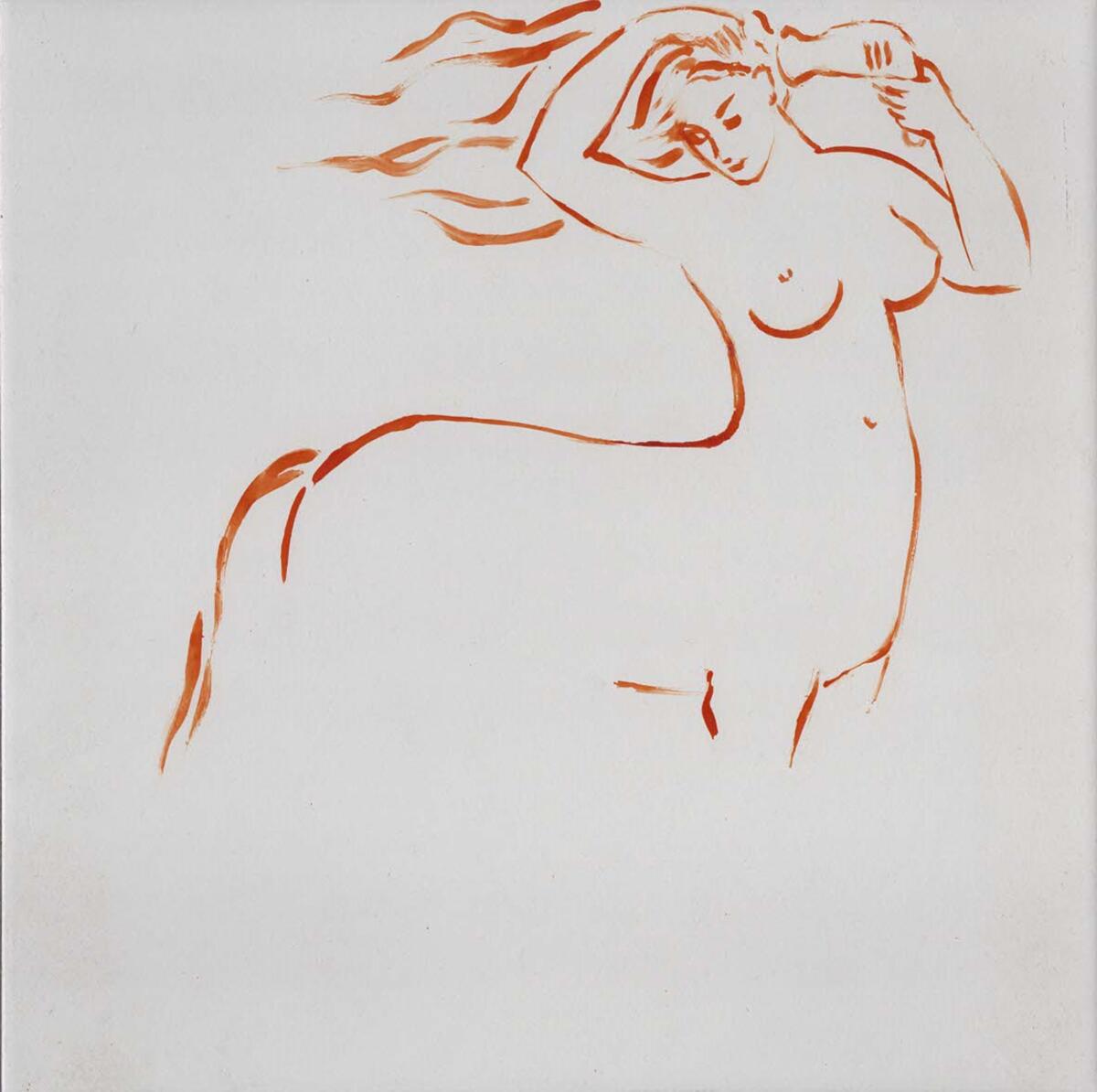

The themes of fear, anxiety, and brandishing pain can be traced in White Room by Valeria Barbas, or Act of Empathy by Anna Galatonova, and in my book DO NOT breathe. During the quarantine, Barbas created a body diary, referring to her experience, memory and observations, adding the “voices” of others suffering from various forms of depression from the Republic of Moldova, which she collected during this time. Galatonova sought to survive the pain, physical and/or mental, of herself or that of someone (or something) else, with the help of photography. For example, during quarantine, her cat was diagnosed with an incurable disease. The veterinarian prescribed injections, for which she had to wrap the cat in cloth in order to administer without being attacked. According to the artist, the photo series was an attempt to transform the experience of trauma into a visual image in order to both abstract it and to remember it in a new way.

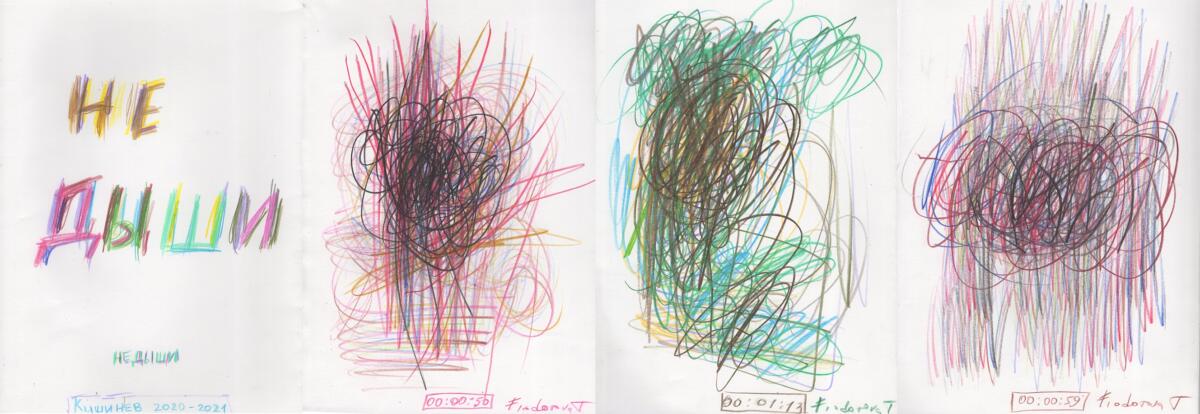

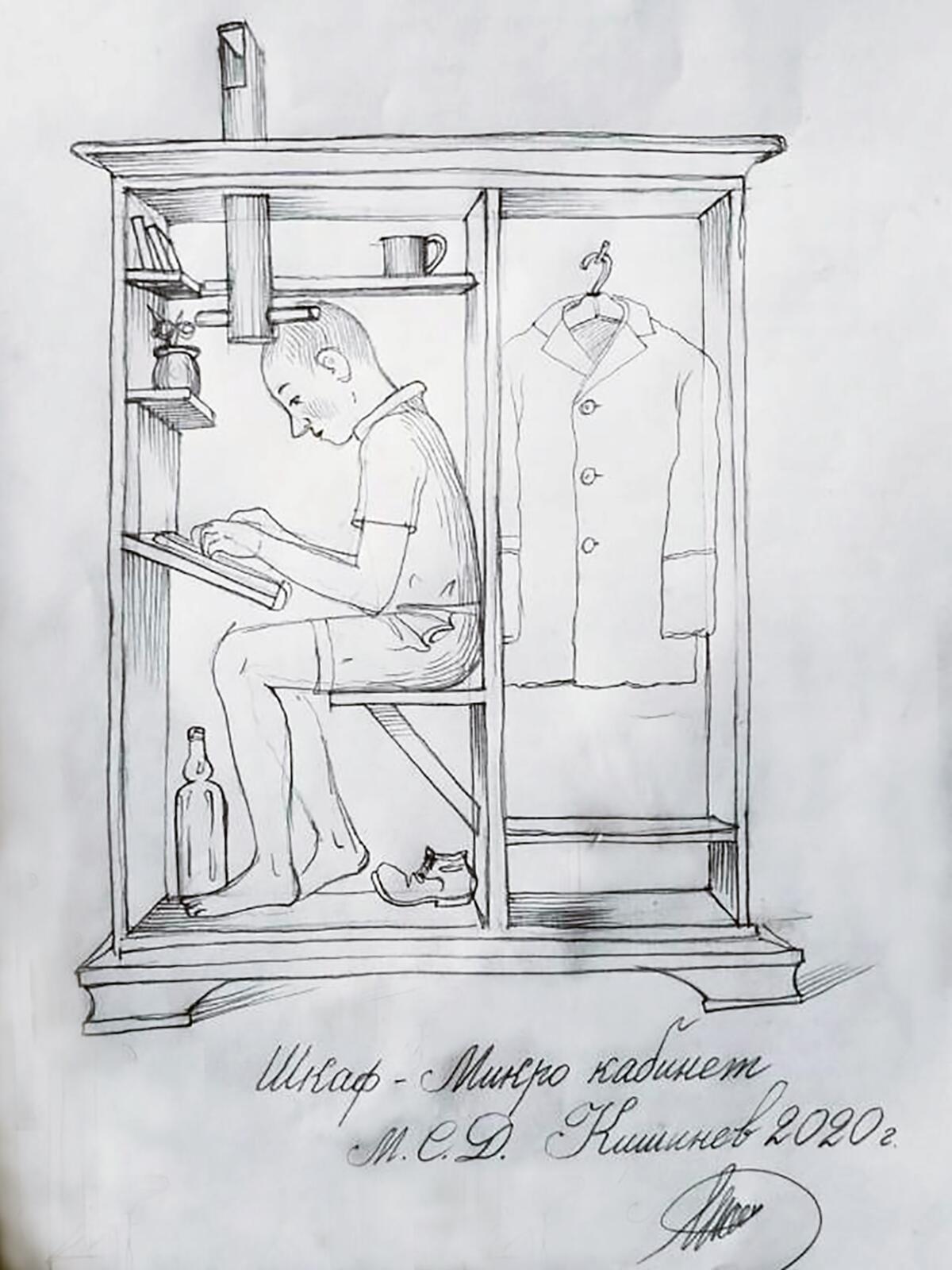

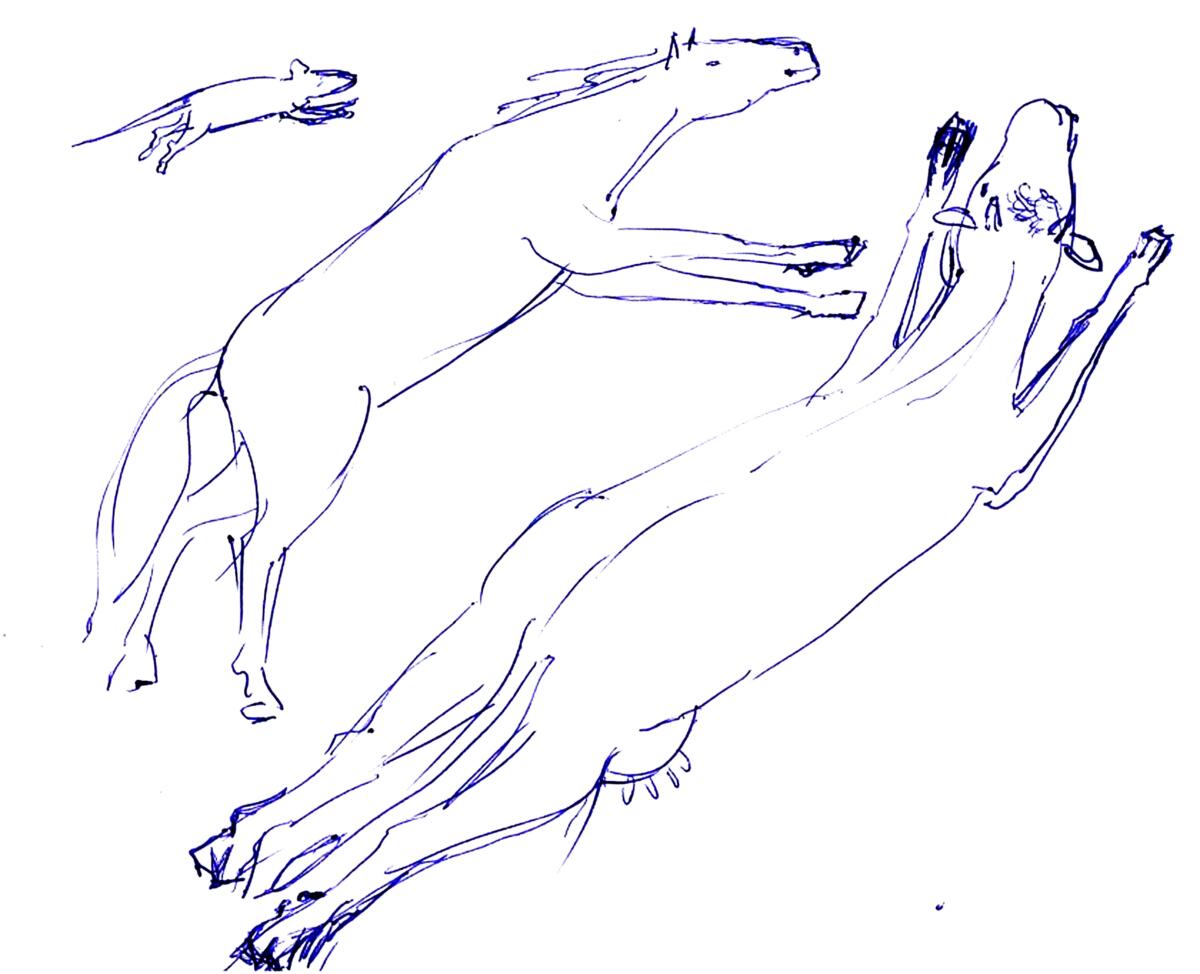

With my book Don’t Breathe, I tried to do something with the fear of contracting the virus. I noticed that when I was in crowded places, I tried to hold my breath until I was in a place with fewer people around. I still do it today. During the two-month isolation from March–April 2020, I very actively practiced yoga and pranayama– special breathing practices, including breath-holding. I also felt a strong desire to draw, and so I brought these two practices together, exploring my own body and its possibilities. The resulting book features a series of abstract drawings made during exercises of holding my breath for as long as possible.

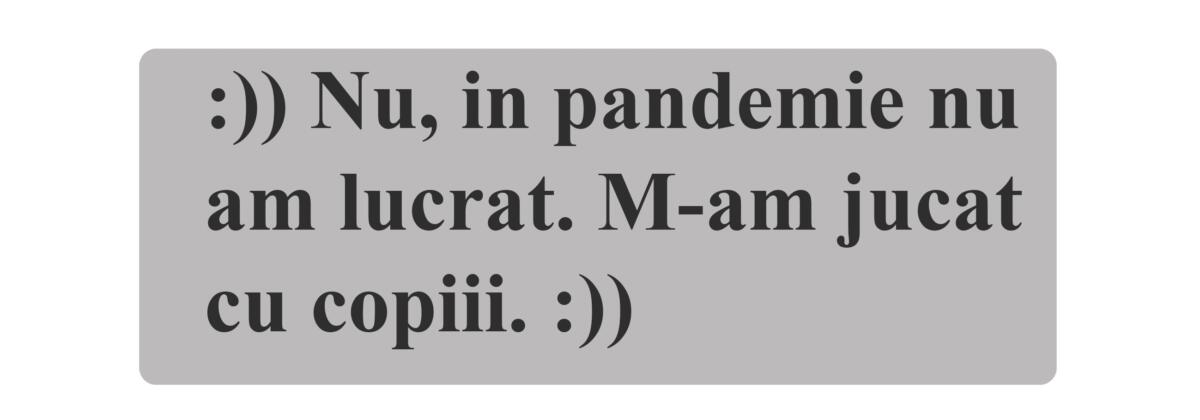

The show featured not only the works of artists and activists, but also the records of our online communications during that period. For example, while developing the project I turned to artists I knew with a request or an invitation to participate. Dmitru Oboroc wrote to me on Facebook that he has no works to exhibit, as he spends all his free time with his children. It seemed to me very important to place this phrase in the general context of the exhibition, since in his case, he is an artist who is also a parent who cares not only about his work, but also about his children.

Some of the artists who took part in Pandemic, Ecology and Artist live abroad – was their experience of the pandemic and isolation somehow different from the experience of artists living in Moldova? If yes, how did it influence their artworks made for the exhibition?

The experience of isolation during the lockdown has been different, of course. In some countries it was only a recommended gesture as at first in Germany, according to Alexandru Raevschi. In Moscow, Ivan Yalanzhi experienced strict control and restricted access to things and in Moldova it was also impossible to leave our apartments, except to go to a pharmacy or grocery store.

Alexander Tinei was lucky to have a dacha located near Budapest which allowed him to have some form of a normal life during the lockdown. This is probably why there are so many plant motifs in his works. Veaceslav Druta, who lives in Canada, wrote that thanks to financial support from the state during the lockdown, he managed to fruitfully develop some of his new projects.

Artists, like everyone else, experienced isolation and waited for the moment to return to their work, to their projects, to their ideas. After a year of isolation and restrictions, Pavel Brăila held a “kick off” performance in honor of the opening of the 2020 Euro Cup, which was postponed for a year and began on June 11, 2021, which coincided with the opening day of our exhibition. The performance was held on that day in Marburg, Germany with an online transmission to Chisinau.

Was the direct relation between the artist and the viewer important to the idea of the exhibition? For many months all of us were frightened to breathe the same air, for fear of catching the infectious disease. But this “breathing” also means sharing, or looking for something common, which I think is emphasized in the title of the exhibition.

There was a fear to meet, to hold the opening of the exhibition, and to communicate with the audience. Before, breathing together was so natural for people but these days it has taken on a new value. At that time, it was important to regain what was lost, to learn to meet and communicate again, to connect Moldovan artists. It was important in the context of current divisions and segregations, to be together at least virtually, or in the format of an exhibition.

In this context it’s worth mentioning Book without text by Igor Shcherbina. The work presented in the exhibition is interactive in that the artist invited the viewer to become his accomplices in completing the book. For a dialogue with the viewer, the artist offers to decipher his phrase – an abstract drawings that resemble QR codes and can be recognized as messages. One must try to decipher the images in order to understand their meaning. Or, to express their attitude towards them, without resorting to decoding.

Observational capitalism and competitive liberalism, as we see it, especially during the pandemic, are alienating us from each other no matter what country you live in. All we can do at this moment is leave our mark. Everyone has to take responsibility, especially artists who play a specific role, especially when the state and its institutions fail, art and culture can fill these gaps. It is artists, as indicators of modernity and transformers of society, who, in times of isolation and borders, can help make social problems more visible and provide alternative futures. That is why it is so important to share our experience.

***

The exhibition Breathing with One Voice took place at two sites in the city of Chisinau: in the Museum of the History of the City of Chisinau and in the independent cultural space Zpatiu. Later it will travel to the Information and Legal Center “Akkolada” in Transnistria. The exhibition features works created by Moldovan artists from March 2020 till June 2021. The project was created in the frame of the Platform CULTURE, with the support of the EU funded Confidence-building program (EU-SBM V) and implemented by the United Nations Development Program.

Edited by Ewa Borysiewicz and Katie Zazenski

Imprint

| Artist | Anna Galatonova (Tiraspol), Elena Stepanova, (Dubossary), Valeria Barbas (Chisinau), Alexandru Raevschi (Chisinau-Marburg), Ramin Mazur (Rybnitsa -Chisinau), Ivan Yalanji (Kopchak-Moscow), Victor Ciobanu ( Măcăresti-Chisinau), Fiodorova Tatiana (Chisinau), Igor Shcherbina (Chisinau-Moscow), Mikhail Kalarashan (Rybnitsa -Chisinau), Dmitru Oboroc (Nisporeni-Iași), Pavel Braila (Chisinau -Berlin), Veaceslav Druta (Chisinau – Quebec), Ghenadie Popescu (Floresti-Chisinau), Lilia Nenescu (Chisinau), Alexander Tinei (Budapest-Chisinau), Marik Verlan (Chisinau) |

| Exhibition | Breathing with One Voice |

| Place / venue | 11-22 June 2021 Chisinau City History Museum / June 12, June 18 -19 2021 at Zpatiu space |

| Dates | 11-22 June 2021 at Chisinau City History Museum |

| Website | zpatiu.wordpress.com/ |

| Index | Alexander Tinei Alexandru Raevschi Anna Galatonova Dmitru Oboroc Elena Stepanova Fiodorova Tatiana Ghenadie Popescu Igor Shcherbina Ivan Yalanji Lilia Nenescu Marik Verlan Mikhail Kalarashan Pavel Braila Ramin Mazur Tytus Szabelski Valeria Barbas Veaceslav Druta Victor Ciobanu |