The origins and development of performance art in Europe and North America are myriad. Poland, in particular, has a range of sources that account for its development, from theatre to architecture. What is more, in Polish post-war art, the line between performance and conceptual art is often blurred, with the two genres drawing on one another for both technique and execution. The performances of Ludmiła Popiel and Jerzy Fedorowicz reflect these myriad sources and influences, and this article will analyse the work and writing of these two artists in both the local and global context of conceptual and performance art, demonstrating their unique contributions to the genre.

Tensions between perception and reality. Objective Landscape

In Pejzaż obiektywny [Objective landscape], an “artistic activity” by Popiel and Fedorowicz carried out at Lake Jamno during the pleinair in Osieki 1973, six participants are instructed to hold a blank canvas in front of them, with their backs to the shoreline of the lake, while two participants mark the line of the horizon on the canvases—across all six —with a piece of string, the position of which is verified through a camera lens. On the day of the performance, the participants are given the canvases at 11:45 a.m.; at 11:55 a.m. the horizon is marked with a piece of string; it is verified through the lens at 11:58, and at noon, a “trace” of the horizon line is left on the canvasses in the form of that string. Later, the artists paint the bottom of the canvasses blue, demarcating the separation between skyline and earth. The action attempts to confront perception with reality—the perception of the horizon line and its reality in one’s field of vision and on the canvas, as captured by the artist-participants.

The piece underscores the gap between observation and that reality, the gap that always exists between life and art. In fact, in attempting to create an “objective” landscape, the result is completely subjective. The painted canvasses reveal a horizon line that is uneven, due to the angled positioning of the canvases in the participants’ hands. Even the use of precise timings of each action in the piece, combined with the use of the camera, often erroneously considered an apparatus that can capture an “objective” view, cannot counter the inherent subjectivity that occurs when a living, human subject is involved in image-making.

From the 1950s through the 1970s, experiments in Polish theatre, namely those of Tadeusz Kantor and Jerzy Grotowski, formed the basis for the development of a newly emergent artistic genre called performance art. Grotowski’s activities in particular, and his concept of Laboratory Theatre, which focused on the psychological processes of the group and involved the actors and viewers becoming co-creators in the work of art, through their interpersonal relations, have relevance for the type of performative work being done by Popiel and Fedorowicz.

The performance also plays out as a negotiation of making meaning between the artist and the participants that is often characteristic of performance art, and consistently remained the artists’ approach. In a statement made eight years after that performance, Popiel and Fedorowicz commented on the significance of this relationship between artist and viewer, and their cooperation, for the creation of meaning in the artwork. In the context of the exhibition Formy nikłe [Faint forms], Fedorowicz stated: ”The chance of understanding between the artist and the viewer has been outlined more clearly than ever before. This does not mean that the language of art has become easier. On the contrary, intensified effort is required on both sides. Both in the sphere of imagination, concentration, attention, and with regard to the simple willingness to establish interpersonal CONTACT based on disinterested intentions and behaviours”.[1]

The 1970s was precisely the time when artists were attempting to actively engage their viewers and involve them in the creation of meaning, challenging them to wake up from their usual role as passive spectators. Interestingly, the exhibition for which this statement was written was cancelled at the last minute following the imposition of martial law in Poland in 1981. While this political crackdown resulted in a number of exhibition cancellations and gallery closures, it was not surprising for an exhibition by artists who call on the active participation of their viewers in the artistic arena to be prohibited by the authorities at a time when they were trying to suppress the active engagement of citizens in the socio-political arena.

The performance Objective Landscape bears interesting formal similarities to Russian artist Francisco Infante-Arana’s use of mirrors or tinfoil in nature to confuse the natural landscape and create a tension between perception and reality. For example, in 1966 he wrapped a slim tinfoil band (a few inches wide) around several trees that were growing at various distances from one another in the forest, calibrating the width of the bands and aligning the bands to create the appearance of a single horizon line when viewed from a certain point in the distance. The placement of the foil creates the illusion that it constitutes one continuous line in space between the trees, but the bands are placed at varying heights on the tree trunks. Due to the reflective nature of the material, the installation also creates the illusion that the line is not, in fact, solid, but a transparent space interrupting the trunks of the trees. Similarly, Infante has wrapped parts of branches of bare bushes in tinfoil, creating geometric patterns in them that would not exist naturally, using a multi-dimensional object as if it were a flat canvas. The reflective surface of the tinfoil creates a confusing image, one that appears at the same time transparent yet solid. Infante’s use of mirrors in the landscape also frustrates the viewer’s perception of the landscape, bringing sky into the land and vice versa. It is interesting that Infante’s experiments, like Popiel and Fedorowicz’s, also date to the 1970s, a time when the object of art was diminishing in importance in comparison to the process of both creating and understanding the work of art. Both Infante and Popiel and Fedorowicz create conceptual games in their work wherein the piece exists primarily in the viewer’s perception of it.

Also of note is the fact that these experiments by Popiel and Fedorowicz, with regard to the perception of reality, took place in the context of performance, as opposed to exclusively painting or drawing. While the line of drawing and paint on canvas is used in Objective Landscape, it is the motion and physical presence of bodies that facilitates the creation of the piece, which ends up taking the form of a scientific experiment. Performance, as a genre, emerged at a time when artists wanted to expand their work from the boundaries of the canvas, and bring it into the real world. Many North American artists also brought their performances outdoors, to escape the commercialized space of the gallery, while in Eastern Europe, this shift occurred as a way to find a space of freedom in an otherwise closely monitored state. Examples of this are Romanian artists Ion Grigorescu and Dan Perjovschi’s performances in the countryside, and numerous examples of outdoor performances by Czech performance artists. While the plein-airs were monitored by the authorities, the unofficial outdoor setting, as opposed to the official space of a state gallery, often offered artists a bit more leeway.[2] Similarly, land artists across the globe sought to use the earth as their canvas, thus diminishing the line between art and life. Objective Landscape relies on both of these ideas—of using the landscape as the object of art and the presence and action of the landscape as a way of expanding the limits of art.

Furthermore, the presence of scientific thinking is not surprising, considering the interests of artists in Poland at the time, and in particular the interests of these two individuals, who organized annual meetings among artists, scientists, philosophers and other thinkers in Osieki from 196 to 1981. The meetings enabled the coming together of a range of individuals to confer on and develop the latest ideas in contemporary art, philosophy and science, and engage in activities such as performance art. The artists also participated in the Symposium of Artists and Scientists in Puławy in 1966, and were involved in the Wrocław ’70 Symposium, both of which also brought together artists and theoreticians.

Documentation of the action ‘Objective Landscape’ by Jerzy Fedorowicz and Ludmiła Popiel, 1978, private archive

Whiter than Snow

Another performance that deals with the gap between perception and reality, combining that with a linguistic game, is Bielszy niż śnieg [Whiter than snow] (1978)—an attempt to visualize and literalize the line from Psalm 51:7 “Purge me with hyssop, and I shall be clean: wash me, and I shall be whiter than snow” (King James Bible). Participants received a card that read “whiter than snow”, then stood in a circle on a frozen pond covered in snow, surrounding a cut-out of a human figure in grey fibreboard. Fedorowicz then demarcated a border around the figure with red thread and proceeded with Popiel to paint the grey figure with white paint.

The physical act of creating a white-on-white image recalls a number of other formally similar artistic works, such as Russian artist Kazimir Malevich’s White on White (1918), American artist Robert Rauschenberg’s Erased de Kooning Drawing (1953) and contemporaneous Romanian artist Geta Brătescu’s Towards White (1975), all of which, despite being two-dimensional images, have performative elements. Malevich’s work is an early example of the dematerialization of art that came to pervade the 1960s and 1970s, and the work was praised by Fedorowicz himself. In an interview with Agnieszka Popiel in 2011, he commented: ”White square on white canvas— there was no possibility to go any further. That white square on white canvas is almost invisible, and yet it exists in the painting. And even if it did not exist, then I don’t know if Malevich was a forerunner of conceptualism —after all, he could have left the white canvas and only say that he had a white square on it.”

Fedorowicz labels White on White an “intellectual game” and interestingly refers to the canvas itself as a “libretto”—a record or score of the act of painting itself. In his words: “Everything is translated into visuality or lack thereof, because the same visuality can be acquired by means of a record in a different medium. If we can note it down in such a way that we will have a painting in our eyes, then it’s something amazing. A kind of libretto… Having such a record of a painting—in the form of such a ’libretto’—every viewer will call it into being in a different way, akin to the director of a show.”[3] For Fedorowicz, Malevich’s work, and thus his own work with Popiel, is an investigation into the very nature of what art is, a common trope in contemporary art across Europe and America in the 1960s and 1970s. His use of the term libretto, in particular, brings out the performative element of the piece, insofar as performances were often recorded as instructions that could later be enacted by any willing participant—for example, the scores by Fluxus artists that were circulated and performed across the globe in the 1960s and 1970s. For them, art was no longer the object created by the artist, but was a creative collaboration between artist and viewer.

Romanian artist Geta Brătescu’s photographic performance Towards White (1975) also plays on these ideas—the process of eliminating the subjectivity and primacy of the artist. Whereas in Whiter than Snow it was a fibreboard cutout that disappeared into the landscape, in Brătescu’s piece it was the artist herself who disappeared into her studio, which she gradually covered over in white paper, and then covered herself with white in the final stages of the performance. In both pieces, there is an attempt to make both the subject and the object disappear.

Furthermore, Fedorowicz acknowledges the questioning of the nature of art in reference to both Malevich and his own work. In his words: “The whole sense is in the fact that art investigates itself, it seeks its own borders: when it is still art, and when it ceases to be art. Where art finds itself.”[4] These statements echo those of one of the so-called founders of conceptual art, Joseph Kosuth. For Kosuth, art was a tautology that inherently addressed its very nature. One of his better-known statements reads: “The ‘value’ of particular artists after Duchamp can be weighed according to how much they questioned the nature of art.”[5] For Kosuth, and for other artists working at that time, the boundaries of art were exploding beyond the frame of the canvas or the marble figure. Art became about language, perception, process and action, and this can be witnessed in Whiter than Snow, which uses process and action to interrogate perception of visual images as well as scripture. The artists confirm this in their statement in 1984: “Art—for us is a process, a bridge built for a brief while between the external reality and our intellectual and mental condition, between consciousness and reflection.”[6] This process is clearly evident in Whiter than Snow, which is only complete with the full participation of others. Popiel and Fedorowicz could have easily completed the actions by themselves, but they chose to make the artwork a process and collaboration between themselves and others.

Artistic significance aside, one cannot ignore the spiritual reference of the action, given its title and content. Greenbergian modernism was precisely about “purging” the artwork of all extraneous elements—in a way, creating an artwork that was “whiter than white” or whiter than snow. For Greenberg, painting should only be about painting and not refer to anything else, not poetry, not the external world of reality—it should be pure. Malevich, working well before Greenberg expounded his theories, also tried to purge all excess from his paintings—paring them down initially to primary colours and shapes, eliminating any reference to reality or nature, and ultimately eliminating colour altogether, exclaiming, “I have breached the blue lampshade of colour limitations and have passed into the white beyond: follow me comradeaviators, sail on into the depths.”[7] For him, moving beyond colour and form was a way to merge art and life, and bring art into the infinite realm of the cosmos—which for him was a form of spirituality.

According to Fedorowicz—among others, including Malevich himself—once you have pared the painting down to pure white, there is nowhere else to go. Even Malevich reintroduced colour—and eventually the figure—into his paintings after White on White. Popiel and Fedorowicz’s action demonstrates the futility of aiming for the purity of form that the modernists sought—there is no such thing as whiter than white, except perhaps in the spiritual sense, but certainly not in terms of visual imagery and concrete forms. Even modernist painting and sculpture, which developed in the 1950s and 1960s to the pure forms of, for example, Donald Judd’s industrial sculptures, were called out by critics, namely Michael Fried, for not, in fact, maintaining their purity as sculpture. In circumnavigating the object, the viewer—by his or her very movement— performs around the object; performs the viewing or consuming of the object, which bring it into the realm of theatre, not sculpture.[8] It is for this very reason that once the limits of modernist painting had been reached, the genre of performance art emerged, which sought to introduce— or reintroduce—elements of the real world into the artwork.

Furthermore, with the prospect of maintaining the purity of artistic disciplines null, artists began to use their art to explore the very nature of art, as Kosuth described. So, when Rauschenberg erased Willem de Kooning’s drawing, he raised questions as to wherein lies the art—is it in his act of erasing, is it the tattered paper that once contained de Kooning’s drawing, or does the drawing, and artwork, still exist in its original form, on the paper, even if it is not visible? Whiter than Snow captures these questions as well: is the work of art found in the action of the participants, the idea of the artists, or the final object that is left after the painting of the fibreboard body? These are questions that plague the historian of ephemeral art and participatory art, with their myriad of elements, from concept to execution to the objects left behind.

Romanian artist Geta Brătescu’s photographic performance Towards White (1975) also plays on these ideas—the process of eliminating the subjectivity and primacy of the artist. Whereas in Whiter than Snow it was a fibreboard cutout that disappeared into the landscape, in Brătescu’s piece it was the artist herself who disappeared into her studio, which she gradually covered over in white paper, and then covered herself with white in the final stages of the performance. In both pieces, there is an attempt to make both the subject and the object disappear. These pieces took place around the time when artists in the West perhaps still had hope with regard to the dematerialization of the art object—the idea that one could eliminate the object, and thus the commodity, from the artwork.[9] For artists such as Brătescu and Popiel and Fedorowicz, the concern was less with eliminating the commercial object and more with probing the nature and limits of art.

Poland and the Neo-Avant-Garde

Fedorowicz and Popiel seemed to follow the Greenbergian idea of the artistic purity of the avant-garde, a polemic that was laid out in Poland by Wiesław Borowski in his 1975 text published in the Warsaw-based journal Kultura, “Pseudoawangarda” [Pseudo-avant-garde].[10] The text divided the Polish art world according to Borowski’s view of what avant-garde art should be—completely elevated from the everyday. In implicating artists as part of the “pseudo-avantgarde”, what he was really doing was dividing the art world into those associated with Warsaw’s Foksal Gallery and those not. Like Borowski, in his writings Fedorowicz maligns artists such as Andrzej Partum and Anastazy Wiśniewski—artists who, in his view, are too concerned with pragmatism, or art’s opening up to reality.

That said, Fedorowicz and Popiel’s work also bears similarities with those artists on the opposite side of Borowski’s “divide”. For example, in their focus on process as opposed to object, as noted in the text for the Language of Geometry catalogue, quoted above.[11] In emphasizing the act of creation, the artists align themselves with the likes of KwieKulik, who incorporated the process of creating and documenting the artwork into the work itself. And in acknowledging the connection with “external reality”, they demonstrate concerns shared by the likes of Natalia LL and Jan Świdziński, whose theory of “Contextual Art” demands that an artwork be understood as part of its wider context.

The 1970s was precisely the time when artists were attempting to actively engage their viewers and involve them in the creation of meaning, challenging them to wake up from their usual role as passive spectators. Interestingly, the exhibition for which this statement was written was cancelled at the last minute following the imposition of martial law in Poland in 1981.

Fedorowicz would probably not agree with this evaluation, given his vehement criticism of those included in Borowski’s pseudo-avant-garde, such as Andrzej Partum. In his highly polemical text, “Unconventional Kitsch”, he makes reference to what he calls “elitist contextual kitsch”, a nottoo- subtle reference to Jan Świdziński’s concept of “Contextual Art”. Further, he indicts other colleagues, notably Andrzej Partum and Anastazy Wiśniewski, for their author’s galleries, stating that this kitsch “is insistent. It mostly operates via mail correspondence, but not only. All those different ‘POETRY BUREAUS’, non-existent ‘YES GALLERIES’, ‘NO GALLERIES’, and so on.”[12] In this text, Fedorowicz laments the fact that kitsch, as non-art, has shifted from being merely an object to also occurring in conceptual art, manifested as “professionalism and perfection [and] … organizational activities that serve artistic practice.”[13] That said, Popiel and Fedorowicz also occupied themselves with the organization of activities, namely the Osieki plein-airs, though perhaps did not see these as part of their artistic practice, thus exonerating them from their own criticism.

Many scholars have analysed Borowski’s text since its publication, including Łukasz Ronduda, who carefully pointed out that in fact, the neo-avant-garde was more nuanced than simply a divide between the “pseudo-avantgarde” and the avant-garde artists that Borowski’s text praised.[14] Ronduda noted further categories: intra-artistic, what one might call the “hard-line” avant-garde; pragmatist, its opposite; and existentialist, which exists somewhere between the two. This nuance allows for artists to be seen as working in a sort of grey zone between the avant-garde of “pure art” and that which acknowledges and includes the surrounding reality. I would suggest that an artist such as Natalia LL occupies that role. It is for this reason that I find it productive to draw out parallels between Fedorowicz and Popiel’s work and those “public enemies” of Borowski in the existential and pragmatist camp of the neo-avant-garde. I would also argue that Fedorowicz and Popiel’s statements revealing affinities with the work and approach of the so-called enemies of the avant-garde demonstrate that the vitriolic nature of Borowski’s text obscures its real meaning, muddying the arguments therein. It is for this reason that Popiel and Fedorowicz perhaps did not recognize their shared concerns with the likes of Partum and Natalia LL. Nevertheless, what is most crucial, I think, for the discussion, is that all of these artists were seeking to determine what defined the nature of art in the second half of the twentieth century.

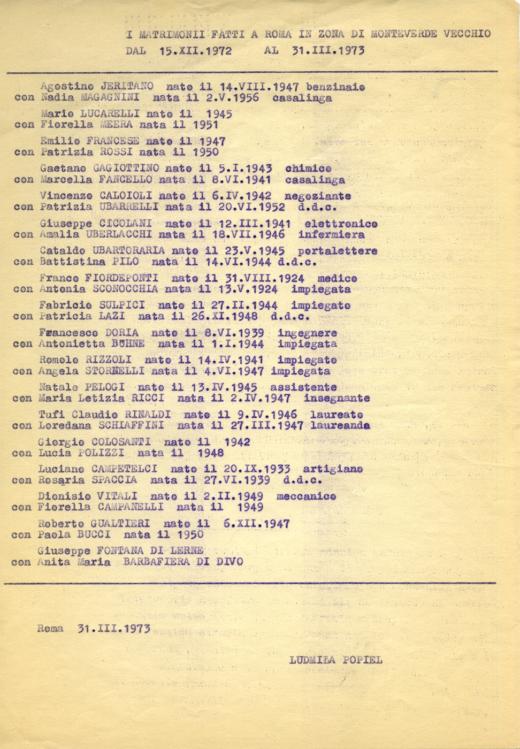

Ludmiła Popiel, ‘I matrimoni fatti a Roma in zona di Monteverde Vecchio dal 15.12.1972 al 31.02.1973’, 1972–1973, typescript, 29 x 21 cm, private collection

Thread

The questions as to wherein lies the work of art are ones that Popiel and Fedorowicz were also asking in their conceptual works that exist only in idea, but not in actual form or execution. For example, Nić [Thread], from 1971, exists only as a drawing, which depicts a thread connecting two banks of the Turów open-cast mine. Similarly, Fedorowicz’s Psychourządzenia [Psychodevices] (1971) were also conceptual ideas that never materialized, emphasizing the need to “manipulate the surroundings in order to generate conditions for the best possible form of interpersonal contact”.[15] This is an interesting and unique aspect of their work, as it combines both the conceptual and the personal. North American conceptualism is usually understood to be focused on not only dematerialization, but also depersonalization, insofar as the work attempts to purge all reference to the individual, to emotion and sentiment.[16] With the above statement concerning interpersonal contact, and as other works in the oeuvre of Popiel and Fedorowicz demonstrate, these artists make a unique contribution to contemporary art by combining the conceptual, the performative and the personal—in the form of the relations between participants and artists.

A similar combination can be found in the conceptual work of Wrocław-based artist Natalia LL. Her Rejestracja permanentna czasu [Permanent measure of time] (1970), for example, charts twenty-four hours in the artist’s life, a film work that involves shots of a ticking clock, marking the temporal aspect of her life, along with scenes of her face and her written name, indicating both signifier (her name) and signified (the artist herself). It is the inclusion of this personal element in her examination of time that is unique. While other conceptual artists, for example On Kawara, examined the passing of time in conceptual art, they did so in a depersonalized manner, capturing only the numerical passage of time, in the form of dates or a sequence of numbers. In Permanent Measure of Time, Natalia LL had to physically endure the twenty-four hours of making the piece without sleep, combining the conceptual and the personal with the performative, as the process of creating the work required the focus and bodily presence of the artist for the entire twenty four-hour period.[17] By creating a conceptual piece that aimed at creating better conditions for interpersonal contact, Popiel and Fedorowicz similarly challenged the notion of the depersonalization of conceptual art, and merged the conceptual with the performative in their work.

Art became about language, perception, process and action, and this can be witnessed in Whiter than Snow, which uses process and action to interrogate perception of visual images as well as scripture. The artists confirm this in their statement in 1984: “Art—for us is a process, a bridge built for a brief while between the external reality and our intellectual and mental condition, between consciousness and reflection.”

From the 1950s through the 1970s, experiments in Polish theatre, namely those of Tadeusz Kantor and Jerzy Grotowski, formed the basis for the development of a newly emergent artistic genre called performance art. Grotowski’s activities in particular, and his concept of Laboratory Theatre, which focused on the psychological processes of the group and involved the actors and viewers becoming co-creators in the work of art, through their interpersonal relations, have relevance for the type of performative work being done by Popiel and Fedorowicz. Across the pond, Michael Fried’s observation regarding the significance of the movement of the individual around minimalist sculpture acknowledged the activity of both the artist and viewer as part of the artwork, leading to the development of performative work. In this sense, Popiel and Fedorowicz’s use of performance, movement and the involvement of the viewer thus challenges the notion of their position as the so-called “pure” avant-garde artists that Borowski described in 1975. Rather, they represent a more nuanced approach to this strand of avant-garde art.

The Body in space. Synchron

The notion of the human body in relation to both space and other individuals is combined with the red thread that continues through Popiel and Fedorowicz’s work: that of perception versus reality. The action Synchron took place in Dłusko on 9 February 1977. The participants gathered indoors and were divided into three groups, each in a separate room. Participants in each group had the same task: to choose one of the many possible directions to form a straight line across the room. The participants also had to explain the reason behind their choice, and those choices were documented by the artists. The next day, the artists materialized those crossings, from the three groups, outdoors, and presented this to the participants. Much like Objective Landscape, the piece relies on the human body and its interaction with space to make line and distance concrete, by capturing it in the form of a piece of wood or string. What is more, the piece maps the artificial space of a man-made interior onto the natural space of the outdoors, demonstrating what happens to the patterns of our movement, which are confined when indoors, when transferred to a natural setting with no man-made limits. The lines, when placed outdoors, become an abstract and concrete version of an intangible yet real line of sight in the eye of the beholder. In some ways, this piece performs the opposite of what North American land artist Robert Smithson’s displacements did: whereas with those he brought abstracted elements of the landscape, such as sand and stone, into the space of the gallery, Popiel and Fedorowicz’s Synchron transplants the imaginary space of a man-made construction, and the mind, to the natural space of the outdoors.

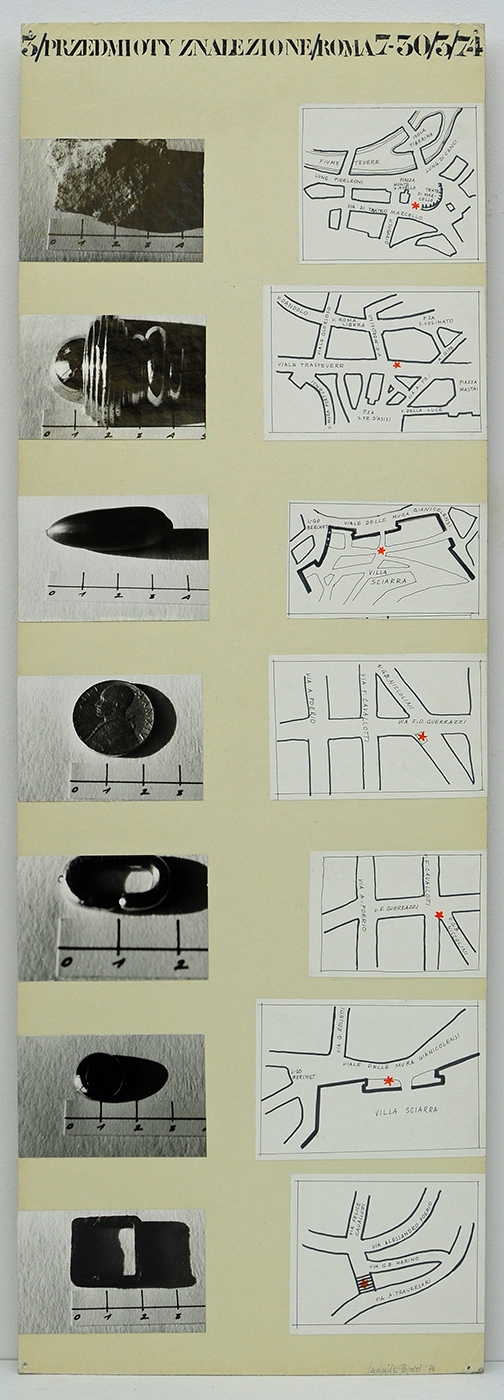

Found Objects and I matrimonii fatti a Roma

The idea of mapping the movement or spatial perception of the individual through form can also be seen in Popiel’s Przedmioty znalezione [Found objects], made during her 1974 stay in Rome. In this piece, she mapped he territory of the city through a series of objects found on the streets as she encountered them. Here, the artist attempted to capture the ephemeral (her walk and movement around the city) through the use of concrete, material objects— the ephemera of everyday life—reversing the dematerialization of art. Even the manner in which she exhibited them, next to a handmade ruler to provide measurement, demonstrates this desire to make concrete that which cannot truly be captured. The piece also introduces a personal and almost autobiographical element, by using objects that captured the artist’s attention, perhaps through an emotional response, on her private walk and encounter with the city.

Similarly, the piece I matrimonii fatti a Roma in Zona di Monteverde Vecchio dal 15 XII 72 – al 3 II 73 [Marriages in Rome in the Monteverde Vecchio area from 15/12/72 to 31/2/73], a typewritten page containing the names and birthdates of the couples married in one of the city’s parishes during the period Popiel was living there in 1972–1973, attempts to make solid and concrete a particular performative action and a very personal moment in human relationships, recorded as mundane and everyday information. Once again, the artist injects the personal with the conceptual and performative, creating a unique hybrid of contemporary art.

The Situationist International, working in Paris during the previous decade, also aimed to encounter the city in which they found themselves in different ways. Guy Debord’s derive encouraged individuals to embark on a walk around the city without a set path, rather following whatever piqued their interests. Popiel’s Found Objects has a similar approach, yet expands beyond the purely ephemeral to focus on concrete objects that, while found in various points across the city, are subsequently removed from those geographic points and abstracted when placed in the gallery, thus becoming detached from their physical space but representing that space metaphorically. Whereas the Situationists were aiming to move away from consumer-driven contemporary life, Popiel focuses on those consumerist objects and reclaims them as objects of art.

Theory of Low Activity

In 1972, Fedorowicz authored Teoria niskiej aktywności [Theory of low activity], his treatise emphasizing the concept expressed in the work of art and diminishing the artist’s role in creating it. This underscores the artist’s utilization of performance in conceptual art to foreground the process of creating meaning that occurs in the interaction between artist, viewer and artwork. Popiel and Fedorowicz’s work combines the use of the human body and the movement of the individual to explore concepts of spatiality, perception and reality. While Popiel and Fedorowicz were wellconnected with contemporary artists, scientists and philosophers through the Osieki Plein-Airs, they were also connected internationally, recognized by collectors and promoters of experimental contemporary art at the time.

For example, the documentation of their work A-B Metr [A-B metre] is in the Klaus Groh archive, one of the largest collections of European conceptual art and mail art. Popiel’s mail art piece Communication Paper was sent to the Richard Demarco Art Gallery in Edinburgh in 1972. Groh and Demarco are among the most important collectors and supporters of art from East-Central Europe in Western Europe, and the recognition and inclusion of their work by these individuals points to a position on the global stage as well. That said, their resonance in the global art world has not been as great as the likes of their contemporaries, who perhaps travelled more widely and whose work was more translatable to international audiences.

Ludmiła Popiel died in 1988, thus ending a prolific career, while Fedorowicz survived her by another thirty years. Their work from the 1960s and 1970s was significant in terms of art production and theory, and their unique understanding and implementation of performance and performative gestures in their work. They also contributed meaningfully to the development of contemporary art in Poland, by organizing meetings and gatherings of artists in Osieki. These offered distinctive opportunities for artists to network with one another, experiment, and witness the latest developments in contemporary art. At the plein-airs, artists learned from one another what they may not have been learning from their instructors at the art academy. Popiel and Fedorowicz, through both their art and their organization of these events, filled that gap and made a significant contribution to Polish conceptual and performance art history.

[1] Jerzy Fedorowicz, statement for the exhibition Formy nikłe, Koszalin, 1981.

[2] The extent of interventions of the authorities in artists’ activities during official plein-airs in Poland varied. One example of the authorities intervening came following an artistic plein-air in Puławy, south-eastern Poland, in 1966. The events and artworks were unconventional and had not been screened by the authorities in advance, resulting in the art historian Jerzy Ludwiński, organizer of the events, being ostracized and having to leave the city of Lublin, where he worked. He moved to Wrocław, where he opened the Galeria pod Moną Lisą (Mona Lisa Gallery).

[3] Jerzy Fedorowicz, quoted in Agnieszka Popiel, “Jerzy Fedorowicz: Rytm życia, rytm czasu, rytm sztuki,” Sztuka i Dokumentacja, no. 18 (2018): 157.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Joseph Kosuth, “Art After Philosophy”, Studio International (October 1969), reprinted in Art and Theory 1900–2000: An Anthology of Changing Ideas, ed. Charles Harrison and Paul Wood (London: Wiley and Blackwell, 2002), 856.

[6] Artists’ statement in the exhibition catalogue Język geometrii (Warsaw: CBWA, 1984).

[7] Kazimir Malevich, “Suprematism” (1919), in John Bowlt, Russian Art of the Avant-Garde: Theory and Criticism, 1902–1934 (New York: Thames and Hudson, 1976), 144.

[8] Michael Fried, “Art and Objecthood”, Artforum (Summer 1967), reprinted in Harrison and Wood, Art and Theory, 836–46.

[9] See for example Lucy Lippard, Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997).

[10] Wiesław Borowski, “Pseudoawangarda,” Kultura, no. 12 (1975): 11–12.

[11] Artists’ statement in the exhibition catalogue Język geometrii.

[12] Jerzy Fedorowicz, “Kicz niekonwencjonalny. Uwagi na temat kiczu w związku z III Festiwalem Kiczu w Poznaniu 1978”, 1978.

[13] Ibid.

[14] See Łukasz Ronduda, Polish Art of the 1970s (Warsaw: CCA Zamek Ujazdowski, 2009), 8–15.

[15] Popiel, “Jerzy Fedorowicz”, 163.

[16] This notion has recently been astutely challenged by Nizan Shaked in The Synthetic Proposition (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2017), where she argues that conceptual works by artists from the 1960s and 1970s, such as Adrian Piper, in fact were not depersonalized at all, but addressed the identity politics that were only to become significant with regard to the art of the 1990s.

[17] I have written about this combination of the conceptual, performative and personal in my essay “Natalia L.L.: Intimate Transfigurations”, in Natalia LL: Secretum et Tremor, ed. Ewa Toniak (Warsaw: CCA Ujazdowski Castle, 2015), 198–213.