The period of the Ukrainian revolution at the end of 2013 and the beginning of 2014, and the tragic events that followed – the annexation of Crimea and the military confrontation in the east of the country – became one of the most important, prolific and difficult stages in the history of modern Ukrainian art. On the one hand, it was an emotional upsurge, an era when many artists rediscovered the idea of patriotism and gained experience of direct participation in revolutionary and military events, which was by no means a carnival one, compared to 2004. However, the same patriotic upsurge, without which a revolution and subsequent challenges of war would not have been possible, gradually led to the radicalization of right-wing sentiments in the society, the aggravation of nationalism and, as a result, came to its logical end in the form of a hasty decommunization, which was another attempt to erase the historical memory of the country that has experienced many similar episodes in the tough twentieth century.

Nikita Shalenny. From “Where is Your Brother?” series. Color photography, 2013

Ukrainian contemporary art was full of forebodings of the coming social upheavals long before the revolution started in Kyiv. Among the works that most clearly underlined the growing social tensions and the threat of police violence, one should mention Nikita Kadan’s Procedure Room (Процедурна кімната, 2009-2010) – prints on plates depicting police tortures. The others are the Mykola Ridnyi’s project Constant Dropping Wears Away the Stone (Вода камінь точить) nominated for the PinchukArtCentre Prize in 2013, Vasil Tsagolov’s series of paintings The Spectre of Revolution (Привид революції, 2013) and the exhibition Before the Execution (Перед стратою) by Nikita Kadan, Mykola Grokh and Yevgenia Belorusets opened at Karas’ Gallery in Kyiv shortly before the Maidan in October 2013. “The ghost of power and righteousness looms on the horizon,” Yevgenia Belorusets wrote in her text on the project.[1] At this exhibition, Nikita Kadan presented his watercolour series Controlled Incidents (Контрольовані випадковості, 2013), devoted to violence inherent in the politics. Nikita Shalenny was another artist whose works created on the eve of Maidan impress with their resonance with Zeitgeist. In December 2013, he exhibited his project Where Is Thy Brother? (Де брат твій?) — a series of sophisticated photographic life studies of the “new Ukrainians.” The models who posed for Shalenny’s photographs were real officers of the Berkut police special battalion. Another Shalenny’s presentient project was called The Catapult (Катапульта). It was a small model catapult he created in September 2013 with the help of an engineer from the Yuzhmash machine-building plant. Several months later, real catapults will become a symbol of Maidan’s resistance.

Art at the barricades

Initially, the Ukrainian protest was brewing in social media. The intellectuals and creative professionals actively supported it. At this stage, the protest was entirely peaceful. At first it seemed that the 2013 protests will follow the scenario of 2004 and that this “Euro-revolution” will confine itself to festive parties, lively gatherings of art community members in a manner of the Occupy movement, and long discussions on the destinies of humankind that people would have while drinking hot tea and eating revolutionary sandwiches. Oleksandr Roytburd was among the first artists to join this carnivalesque Maidan and to become active during its initial phase, which was pacifist, joyful, and relatively smallscale. Roytburd’s Facebook activity was so remarkable that a few days later he turned into a hero of Maidan and an opinion leader for the members of creative community who actively supported the calls for integration with Europe both on the web and at the square.

The period of the Ukrainian revolution at the end of 2013 and the beginning of 2014, and the tragic events that followed – the annexation of Crimea and the military confrontation in the east of the country – became one of the most important, prolific and difficult stages in the history of modern Ukrainian art.

Now we know that the 2013 protest did not confine itself to innocuous carnival. Already in the early hours of November 30, Ukrainian authorities ordered a brutal crackdown on the students who gathered at Maidan. The following day, when a huge crowd of the city intelligentsia gathered at Mykhailivska Square, became the turning point of the revolution. Very soon, the barricades rose on Maidan. The “Strike Poster” Facebook community appeared already in the early days of the protests. It published revolutionary posters created by representatives of the local creative community and available for free to all Maidan participants. The most famous works of this community were the portrait of the president of Ukraine with a red clownish foamy nose, as well as the poster “I am a Drop in the Ocean,” referring to the “warm ocean strategy” that became known during the first stage of the revolution, that is, a positive peaceful protest.

A new stage of the Maidan began after the crackdown on the students, and it was marked by the construction of ultra-aesthetic ice barricades and the arrangement of a folk art object called the Yolka. Universal aesthetization of protests became the distinctive feature of 2013–2014 Maidan. The protesters’ village behind the barricades was in fact a total installation, and the vivid photographs journalists took on the front-line sometimes seemed staged. In general, the Maidan aesthetics was abundant with references to the futuristic dystopia of the New Middle Ages which imminent coming had been heralded by the world’s leading cultural theorists, such as Umberto Eco.

The protest brought about a huge wave of popular conceptual art. Within several months, the country’s main square saw a series of performances, and some of them caught the worldwide audience. As a rule, these events were organized by the members of creative class, who were not professional artists, although they chose artistic methods to promote their civic position. The most famous of these actions were performed by Lviv musician Markiyan Matsekh who played Chopin’s Waltz in C-sharp minor on December 7, 2013, outside the Presidential Administration building in Kyiv. The photograph of the young man playing the piano in front of the blind wall of the Berkut police instantaneously spread across social media and became a symbol of peaceful civil protest.

On December 29, 2013, another resonant civil action took place in the government quarter – “The Kingdom of Darkness surrounded.” The purpose of the rally, organized by the Maidan Civil Sector, was to reflect the actions of authorities and retarget the negative energy coming from the security forces back to themselves. The rally participants brought mirrors and turned them to the rows of the police officers guarding the government quarter, which, after the violent dispersal of the demonstrators, became a real symbol of the kingdom of darkness.

A number of young artists who sided with the informal Bakteria gallery joined the protest at the early stage. Most active among them – Olexa Mann, Ivan Semesyuk and Andrii Yermolenko. In 2013, they broke into the Ukrainian art scene with flamboyant works that reflected ironically on the most unsavoury sides of the new Ukrainian realities, including the life of thugs (gopniki), roughnecks (zhloby), and other residents of the lumpenized outskirts of Ukrainian metropolises. “Freedom or death!” (or “Freedom or fuckoff!”, as Semesyuk rendered it) and other slogans of Ukrainian anarchism seasoned with a good deal of ironically used vulgarisms and swearwords appeared in the works of these artists long before their powerful re-actualization at Maidan Square. This art went very well with the bright and catching texts Semesyuk and Mann regularly posted on social media. Consequently, Maidan became these artists’ true finest hour: they did not leave the barricades even in the bloodiest days and set up a makeshift gallery and a communication centre at the entrance to Maidan right on the traffic way of Khreshchatyk street. It was very aptly named Mystetsky Barbakan, the Art Barbican[2]. The Mystetsky Barbakan, built in haste of industrial pallets and plywood sheets, has become the main focal point for creative youth concentrated on the Maidan. The improvised street gallery displayed works by Ivan Semesiuk, Oleksa Mann, Andriy Yermolenko, Vitaliy Kravets, Olena Dubrova, and other artists. It held lectures and a flash fiction festival. Importantly, there was a stove, which became a tangible culture-forming factor during severe frosts. The Barbakan artists, who started wearing ironic far-right masks long before the revolution, felt themselves more confident and natural on Maidan than their colleagues of the far-left convictions.

The well-known Kyiv artist Illya Isupov was one of the most active Maidan participants . In addition to his participation in rallies, Isupov posted on Facebook a new series of pictures on hot topics. Considerable public response was received by his work Happy New Year, which depicted the president with a hunting rifle and dead boars against the background of a Special Forces detachment.

Ihor Gusev from Odesa remotely sympathized with the Maidan. In addition to his vivid picturesque Knights of the Revolution series, which he began creating in 2014 under the influence of the Maidan aesthetics and street fashion, the artist wrote on Facebook a series of short poetic sketches on the revolution. These works were later included into the LikeHokku collection[3]:

Ihor Gusev, from the RevoHokku series:

As if attached to the screen

Tea leaves have cooled down

My heart is on the Maidan

***

You called me at night

Candles and a couple of cocktails

Next one was the Molotov

The vivid media activity was one of the key features of the Maidan protests. Never before have political events in Ukraine, let alone documentation of public unrest, been so aesthetized. Maidan spawned thousands of photographs from the hottest spots of the protests. The fiercer the confrontation between the authorities and the opposition was, the more documentary filming on scene became vivid and cinematic. Due to this strange appeal of the Maidan, even in its most sad and ugly manifestations, the protests gave rise to a significant collection of video and photo materials. Eminent artists along with photographers from leading news agencies and ordinary amateurs took part in the struggle for a document. The authors of the most interesting shots of that winter included Serhiy Bratkov, Boris Mikhailov, Vladyslav Krasnoshchek and Serhiy Lebedinsky, Oleksandr Burlaka and Sasha Kurmaz, Oleksiy Salmanov, Konstiantyn Strilets and Oleksandr Chekmenev.

Kyiv artist Vlada Ralko was perhaps the best to catch the growing tragedy of Maidan. Her Kyiv Diary (Киевский дневник) is based on her day-to-day observations of the events.

It is a graphic series that records the emotion and feelings of almost every day between December, 2013 and February, 2014.

Oleksandr Chekmenev, one of the leading Ukrainian photographers, created impressive portraits of participants of the clashes with pro-government forces, as well as a series of photographs of subsequent events in eastern Ukraine – portraits of people who lost their homes, wounded Ukrainian soldiers in a hospital, etc.

The vivid media activity was one of the key features of the Maidan protests. Never before have political events in Ukraine, let alone documentation of public unrest, been so aesthetized.

The Code of Mezhyhirya (Код Межигір`я) was one of the important exhibition projects, which took place in the spring and summer of 2014 in the National Art Museum of Ukraine, situated at the forward position of the barricades during the entire revolution. The author of this book and the artist Oleksandr Roytburd has been curating that project. The exhibition featured artifacts and objects taken out by an initiative group of museum workers from the wealthy estate of Mezhyhirya, abandonded by the fugitive president Yanukovych. The objects of different value were presented as chaotic piles and were designed to immerse visitors in the world of the absurd kitsch of the Ukrainian kleptocratic elite. The project has become one of the most visited exhibitions in the contemporary history of the museum.

Post-trauma

The shock caused by the bloody events at the end of Maidan protests, Russian annexation of Crimea, and the beginning of the war in Donbas have become visibly traumatic for the Ukrainian artistic community. For some artists who actively participated in the Maidan events, this period was the time of a hard post-revolutionary “hangover,” an emotional drama that was hard to express in a single artwork. For others, on the contrary, this very period gave impetus to work on new subjects, problems, and projects. At this time, the most visible phenomenon was the documentaries about the Maidan events made by Oleksiy Radinsky, a film director, an artist, and an activist of the Visual Culture Research Centre (VCRC). Particularly famous was his film People Who Came to Power (Люди, які прийли до влади, 2015), co-authored with Slovakian artist and filmmaker Tomáš Rafa) focused on the initial stages of the conflict in Eastern Ukraine.

In the aftermath of Maidan, Nikita Kadan and Mykola Ridnyi left R.E.P. and SOSka groups, respectively, and entered a new creative phase. Kadan’s project The Possessed Can Witness in the Court (Одержимий може свідчити в суді) exhibited at the Ukrainian National Art Museum in 2015 is one of the most powerful artistic statements on the war in Donbas. In a manner resembling archive funds arrangements, Kadan shelves various items taken from the Museum’s collection on the Soviet history of the region that has been witnessing a violent conflict since 2014. Taken out of the ideological narrative, these things look preposterous and melancholic. At the same time, the shells that landed on the territory of Eastern Ukraine in 2014–2015 were exhibited at the Museum’s staircase landings.

The Shelter (Укриття), another significant Kadan’s work of this period, was presented at the Istanbul Biennale in 2015. The upper part of the installation was an allusion to the exposition of the Donetsk local history museum destroyed by the war, with stuffed deers, tires from the barricades, and shabby walls. At the lower level, there was a bomb shelter with two-story bunks and absurd garden beds, which referred to an episode when the former Maidan protesters eventually started to plant vegetable gardens on the main square of the country.

Mykola Ridnyi showed his programmatic work Blind Spot (Сліпа пляма, 2014) at the Venice Biennale 2015. The artist took the images from media reports about the war in Eastern Ukraine and painted them black, leaving just a small spot intact, which makes a viewer feel the limitedness and irrelevancy of their vision of this fragment of reality. At the same Biennale, the Ukrainian pavilion exhibited yet another strident artwork about the East Ukrainian war: a video installation by the Open Group Synonym for “Wait” (Синонім до слова “чекати”). The artists put surveillance cameras in the homes of people who left for the war, and these cameras showed a real-time footage.

At this period, a new generation of artists made its debut on the national art scene, and Roman Mikhaylov from Kharkiv appeared to be its most interesting representative . In 2014, he created The Shadows (Тіні) project, showing scorched shipwrecks. It reflects upon the Russian annexation of Crimea and the destiny of the Black Sea Navy Fleet that had been a bone of contention between Russia and Ukraine for decades. The installation was exhibited at IX ART KYIV Contemporary in the Mystetsky Arsenal, and then – on the anniversary of the annexation of the peninsula – in the Parliament of Ukraine. Another important Mikhaylov’s project – The Breath of Freedom, (Дыхание свободы, 2013) – started at the Maidan where the artist hot-smoked the paper over the burning barrels in the tent camp behind the barricades. Later, this series developed into gigantic sheets of scorched paper: Fragility, Хрупкось, façade of Église Saint-Merri in Paris, 2014; Imprints of Reality (Опік реального, 2015), etc. After the revolution, the artist Daria Koltsova actively developed the political themes. Her iconic works of the Maidan period include a banner with the extract from the Constitution of Ukraine, where articles, violated by the regime of Viktor Yanukovych, were crossed out with a black marker.

Maria Kulikovska is one of the most interesting and politically engaged female artists of the post-Maidan epoch. Her performance at the 2014 Manifesta in St. Petersburg became enormously famous: to protest against the Russian annexation of Crimea and the war in Eastern Ukraine, she wrapped herself up in the Ukrainian flag on one of the Hermitage’s staircases. Her performance The Raft Crimea (Пліт Крим, 2016) is no less famous, during which she drifted on a float board down the Dnieper without any food reserve in order to emphasise the vulnerability of people who lost their homes and native land after the annexation of Crimea. Before the Maidan revolution, Kulikovska started a series that featured the castings of her own body. Her works from this series were exhibited, among others, at the only contemporary art institution in Donetsk, the Izolatsiya Art Centre. During the armed conflict in Donetsk, the factory that housed this institution was taken over by separatists who executed by shooting the exhibition of Kulikovska’s sculptures Homo Bulla. In 2015, in remembrance of this event, the artist staged her performance Happy Birthday at the Saatchi Gallery in London. In the course of this performance, the naked artist hammered down the soap castings of herself as an answer to the separatists who destroyed her artworks.

In 2017, a big scandal at the edge of art and politics was caused by the far radicals’ raid on David Chichkan’s exhibition Lost Opportunities (Втрачені можливості). This exhibition was probably the first articulate and solid artistic statement that evaluated – critically and at a proper distance – the experience of Maidan. Although the artist himself took part in the 2013–2014 protests, he thinks that the revolution did not reach its goals. Chichkan’s exhibition was widely discussed – as well as the act of vandalism on his show.

After 2014, by analogy with the events of the Orange Revolution, they started talking about the birth of a new generation. However, unlike 2004, when young people were consolidated by the ideas of activism, this generation was not homogeneous.

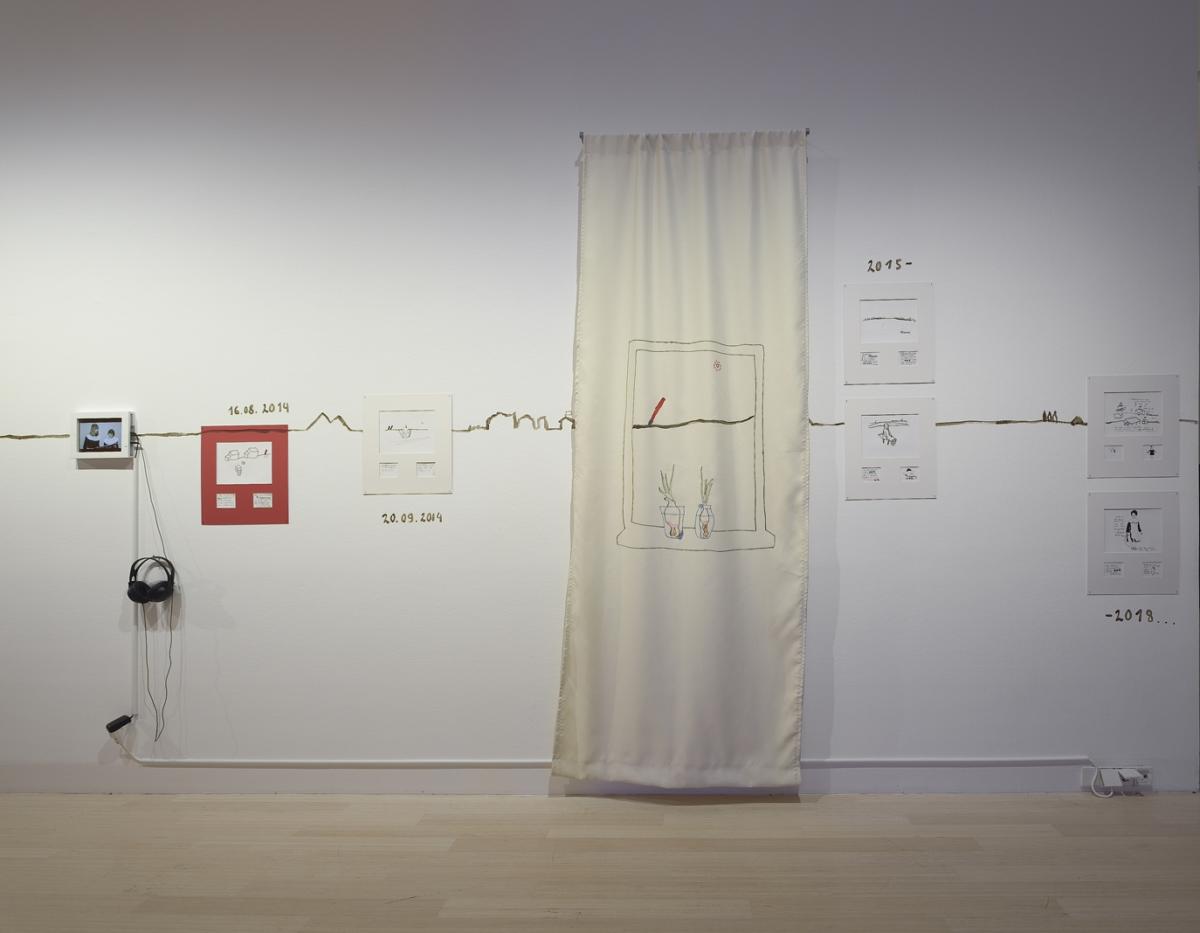

The Alevtina Kakhidze’s project History of Strawberries Andreevna, or Zhdanivka (Історія Полуниці Андріївни, або Жданівка, 2014-2018) is a subtle and piercing reaction to the political crisis in Ukraine. The work covered four years of telephone conversations and meetings between the artist and her mother, who lived in the occupied territories in the Donetsk region. The story started in 2014, when fights between the National Guard and the armed forces of separatists of self-proclaimed Donetsk People’s Republic broke out in Zhdanivka, the Alevtina’s hometown. Mobile service in Zhdanivka functioned only at the town cemetery, and the artist’s mother used to go there to tell her daughter that she was alive. The project included drawings from 2014-2018, video performances, as well as propaganda printed materials reflecting the atmosphere of hatred and absurdity in occupied Zhdanivka. The artist received the archive of the originals from her mother, who collected and handed over to her daughter newspapers, postcards and other propaganda materials of the self-proclaimed Donetsk People’s Republic for several years.

The story continued until 2018, when no mobile provider was already working in Zhdanivka, and mainly retired people remained in the occupied town. On January 16, 2019, the main character of the project, Strawberry Andreevna, the mother of Alevtina Kakhidze, died of a cardiac arrest at the DPR checkpoint, during her trip to Ukraine-controlled territory to receive a pension.

The apostles of individualism. The ghost of a long form

After 2014, by analogy with the events of the Orange Revolution, they started talking about the birth of a new generation. However, unlike 2004, when young people were consolidated by the ideas of activism, this generation was not homogeneous. The pioneers were a group of artists who can loosely be identified as descendants of large exhibitions at the PinchukArtCentre and the Mystetsky Arsenal in late 2000s and early 2010s. An ambition to build an individual career without regard to group dynamics is typical for these authors. Their reference point is the “big” and commercially successful Western art, which once became name-making for the Victor Pinchuk’s art centre. Success stories of Jeff Koons, Takashi Murakami, Yayoi Kusama, and Anish Kapoor mesmerize, and the proximity of this art at the exhibition venues in Kyiv makes one believe that even a native Ukrainian might become the new Damien Hirst.

The access to the unique site of the Mystetsky Arsenal facilitates the emergence of impressive large-scale installations. Here, in the first half of the 2010s, group exhibitions of young artists were regularly held under the curation of Oleksandr Solovyov. The spacious ancient halls of the art complex seem to say: “Think big!” No less important is the PinchukArtCentre Prize for young artists. Artists receive funding for the production of artworks for the final exhibition and prepare their projects under the supervision of experienced curator and art director of the centre, Bjorn Geldhof. Yet, the anticipation of a new original wave coming to the art scene soon faces the harsh truth of life. The revolution and the later tragic events were followed by an economic recession. Big projects were the first to suffer. The cast of individualistic authors focused on the pre-crisis cultural situation and whose large-scale projects needed complex production and spacious venues for presentation, ended up as “passengers without a seat.”

Roman Mikhailov came into the spotlight immediately after the revolution. His works combine a passion for large forms, a focus on artistic intuition, rather than discursive practices, and a deep feeling of a disaster. Mikhailov’s main artworks were created at the height of the hostilities in the east of the country and were united by a theme of fire. Burnt paper from the Imprints of Reality project, charred, wooden objects resembling ships from The Shadows project – Mikhailov’s fire becomes an ambivalent symbol. On the one hand, it carries trauma and pain, and on the other, constructs a new art reality. Later, the artist proceeds from acute political projects to a study of the capabilities of painting. The position of this medium in the system of contemporary art in Ukraine is especially ambiguous. Until recently, Ukrainian art was accused of extreme obsession with painting, but in the second half of the 2010s, it actually disappears from the toolkit of young art. On the contrary, Roman Mikhailov refers specifically to painting in order to search for a new language and desperately examine the dark sides of his unconsciousness. His Fear project (2017) was the most revealing in this regard.

In the mid-2000s, Nikita Shalenny is actively progressing. An architect by training, he makes large and technically sophisticated installations. Black Siberia (2016) was his most successful work of the mid-2010s. Using cheap towels made in China, the artist created a grand-scale panel reminiscent of a scorched forest referring to concentration camps and repressions, the symbol of which in collective memory is still Siberia. In the late 2010s, Shalenny is more and more focusing on the international market and experimenting with virtual reality.[4] Here, he is making tangible progress by exhibiting his artworks in projects with artists of the same level as Olafur Elliasson and Paul McCarthy.

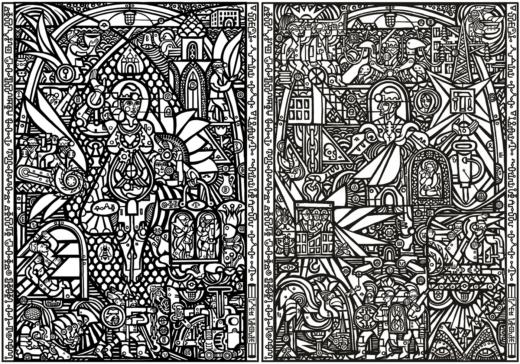

Roman Minin is another representative of the generation that is passionate about titanism. Having developed a recognizable signature style at the beginning of the decade, he embodied it in murals, stained-glass windows, sculpture, and easel works in the 2010s. Working with the aesthetics of late Soviet monumentalism, Minin is experimenting with new materials and technologies. The artist creates commercially successful original artworks that have become one of the recognizable visual symbols of the post-Maidan era.

Roman Minin, Escape Plan from the Donetsk region, 2013

A similar interest in large-scale commercial art is typical for Stepan Ryabchenko. Back in the late 2000s, he began working with digital art. A series of “portraits” of computer viruses, the Virtual Flowers (Віртуальні квіти) project, the large-scale works Death of Actaeon (Смерть Актеона), Lemon chickens will be saved (Лимонні курчата врятуються), and The Temptation of St. Anthony (Спокуса святого Антонія), exhibited in 2011 at the PinchukArtCentre – those bright large-sized digital prints seem to be created for big world fairs and contemporary interiors. Large figurative neon panels was another area in which Ryabchenko worked in the 2010s. The largest of these included the work New Era (Нова ера, 2011-2012, 610×860 cm), created in the Mystetsky Arsenal for a special project of the First Kyiv Biennale “Arsenale-2012.”

Stepan Ryabchenko. All-hearing Ear. Installation, neon, 2015

Conceptual drift

Simultaneously with the artists interested in examination of large-scale forms, a community exists with radically opposite values and attitudes that emerged on the art stage after the revolution. These artists are developing in a neoconceptual vein; they are closer to collective discursive practices. They are focused not on the market, but on institutions. Due to the non-spectacularity and, consequently, the lower cost of the practice, as well as the support of the PinchukArtCentre, which is increasingly leans specifically to this kind of art, these artists are rapidly increasing their symbolic capital in the second half of the 2010s.

The Open Group is most revealing phenomenon of this kind. A team of artists appeared in 2012 in Lviv and became famous thanks to projects in the self-organized Detenpula Gallery. The group was founded by Yevhen Samborsky, Anton Varga, Yuri Biley, Pavlo Kovach, Stanislav Turina and Oleh Perkovsky.[5] At the beginning of its activity, the Open Group involved the legendary Lviv artist and curator Yuri Sokolov in its projects. Active young curators and founders of the Open Archive project[6] Lisa German and Maria Lanko had been working with the Open Group for several years. Thanks to this, Kyiv had quickly learned about this union. The Open Group projects are focused on the study of the society phenomenon.

In 2019, the Open Group came out as a curator of the Ukrainian pavilion at the Venice Biennale. It presented the project The Shadow of Dream[7] cast upon Giardini della Biennale (Падаюча тінь “Мрії” на сади Джардіні). The Venice presentation had been preceded by a scandal involving the second applicant for the participation in Biennale – Arsen Savadov. Ironically, the situation had radically polarized this very society that the Open Group is examining. Having announced the project as the flight of the largest Soviet cargo plane Mriya over Venice, the artists maintained the suspense to the last. “All” Ukrainian artists (those who had checked in the application system) were announced as participants in the project. Hundreds of ceremonial participants of the pavilion is the witty trolling of the contemporary art system and the Biennale itself as an event for the chosen ones, with its elitist pathos. The expectations for the “show” had not been satisfied. Ultimately, the project became in a way a symbolic story telling how nobody flew anywhere, and the entire art part came down to discussions about whether the failed flight was an art in the first place.

In 2015, the Method Fund union[8] appeared in Kyiv. The establishers of the initiative included artists, curators, art historians and teachers Lada Nakonechna, Ivan Melnychuk, Kateryna Badianova, Tetiana Endshpil, Olha Kubli, Denys Pankratov. The Fund is focused on changing educational standards and studying the phenomena of socialist realism.

PinchukArtCentre Prize for Young Artists is an important centre for the outspread of conceptual practices and a tool for their legitimization in the second half of the 2010s.

Anna Zvyagintseva is especially remarkable artist in this respect, whose works can be defined as “emotional minimalism”, and Mykola Karabinovych, who had received in 2018 the first special award of the art centre for his work Voice of Subtle Silence (Голос тонкої тиші).[9] By the end of the 2010s, one can talk about the transformation of neoconceptualism into one of the main trends of young Ukrainian art, supplementing and strengthening the community that appeared in the mid-2000s based on R.E.P. and SOSka groups. Prostory journal, which focuses on art issues, becomes the main media platform for the community of conceptually oriented artists in this period.

Greater Ukraine. Nomads with the homeland in a smartphone

Jacques Lacan said that desire to be somewhere else can be no less strong than sexual drive. This statement is especially true in a world where borders between states and cultures are blurring. Contemporary people increasingly choose to live outside their tribal area, while often maintaining communication with their communities through an intricate web of social networks and tags. On the other hand, one can interact with completely different contexts without going anywhere, but staying at home only physically.

As in past decades, young artists, art historians, curators are leaving their homeland in search of new meanings, a more comfortable life, and simply because mobility is one of the main fetishes of our time.

Throughout its difficult history, Ukraine regularly experienced outbreaks of migrations of cultural figures. In the early twentieth century, active young artists travelled to Europe to explore the uncharted archipelago of modernism. In Soviet times, there was a constant tangible outflow to Moscow, and after the collapse of the USSR, there was a big wave of migration to the West and Israel. In the 2010s, with the simplification of traveling abroad in the wake of the economic recession and post-revolutionary hangover, there was a new round of displacements. As in past decades, young artists, art historians, curators are leaving their homeland in search of new meanings, a more comfortable life, and simply because mobility is one of the main fetishes of our time. An important reason why many choose to flee is the lack of high-quality up-to-date art education in Ukraine and underdeveloped institutions that do not promise bright prospects for young people.

The key factor is the authors’ self-identification and their presence in the art process at the level of participation in projects and online discussions. Some receive education abroad and come back. Some leave, but retain their ephemeral homeland, located on a laptop or smartphone screen. Today we can speak about a whole wave of authors who are virtually active in the Ukrainian context. These are – Mitya Churikov, the artist of the R.E.P. group who was educated in Germany, Zina Isupova, a graduate of the Rodchenko School, Nina Murashkina who lives in Moscow and moves between Ukraine and Spain, and many students who annually enter international art schools. Dozens, if not hundreds, of young artists settle in neighbouring Poland. Among them – Vasily Savchenko, Oleksandr Sovtusik and others. Outside Ukraine, there are two members of the most significant art association of the late 2010s – the Open Group. Art critic and – since recently – photo artist Anatoly Ulyanov who fled at the end of 2000s, photographer Natalya Masharova, curator Olena Chervonyk are active in social networks despite the thousands of kilometres separating them from Ukraine. Some, such as art critic Asya Bazdyreva, turn for some time into a nomad globe-trotter, moving around the world from project to project. These are just a few random examples from an ocean of names and destinies, less and less limited today by “residence permit”.

One can treat critically such global exodus, since the similar processes took place in the twentieth century, when Ukraine repeatedly lost the most important representatives of its art. On the other hand, global references certainly enrich the local environment, and the importance of the national element in the artistic process, obviously, is gradually disappearing. What is still important is the maintenance of ties with the community, and the physical factor here almost does not matter.

Female revenge

In recent decades, art processes in Ukraine are synchronized with global ones. This is also true for one of the main trends of the second half of the 2010s – the re-actualization of the conversation about the role of women in culture and society. The history of Ukrainian art comprised a whole galaxy of talented artists.[10] However, until the 2010s, the role of women in the art process was basically limited to secondary positions. Even female managers rarely got senior positions. Despite the predominantly female collectives of most central museums, representatives of the “stronger sex” still often become their bosses.

In the 2010s, there was a fundamental (although, at first glance, inconspicuous) upheaval. Today, if you take a look at the balance of power in the Ukrainian art establishment, the disproportionate presence of women in literally all positions is striking. Directors of institutions, curators, journalists, chief editors of art publications, art critics, gallery owners, members of foundations and all kinds of private initiatives… If ten years ago, there was about 40 percent of the female top agents in Ukrainian art, today this figure is probably approaching to 80-90 percent. Some may say that women took over the management of the art sphere as a low-competitive environment with still critically few money and public recognition. One way or another, art, indeed, becomes a women’s territory.

After all, many subjects, which Western society came to discuss only at the end of the twentieth century, have been spoken out in the USSR since the 1920s. There was a strange mix of feminist rhetoric and extreme misogyny in the Soviet Union. The fixation on poverty and minimalism was reinforced by the post-war trauma. For the lack of men who died in the war, women took over the traditionally male professions – they had been building the Kyiv metro, working hard on collective farms, and raising children alone. Consequently, by the collapse of the USSR, Soviet women were not so much concerned about equality, but the opportunity to regain their right to femininity. In the 1990s and 2000s, freedom was the right to be, among other things, a “subtle doll.” Several generations of post-Soviet women had been living in the shadow of a dream for fortune of female characters of popular soap operas, supported by the prosperous prince. Consequently, Ukraine gained a notorious reputation as a bride factory.

The desire to declare one`s subjectivity to its full extent came only in the 2010s. This does not mean that there was no discussion about feminism in Ukraine before. This issue has been indirectly represented in art since the 1990s, particularly during the exhibitions that problematized the role of women.[11] In the early 2000s, Olesya Ostrovska-Lyuta curated one of the first distinctively feminist exhibitions at the Centre for Contemporary Arts at NaUKMA. Curator, artist and activist Oksana Bryukhovetska has been organizing feminist exhibitions at VCRC since the late 2000s.[12] In the 2010s, the feminist topics have been developed by Tamara Zlobina, a researcher and chief editor of the Gender in Details online-media.

The symbiosis of the rave spirit, which unexpectedly returned to Ukrainian art in the midst of a severe post-traumatic crisis, and acute political meanings, is perhaps the most characteristic feature of the second half of the 2010s.

Over the past thirty years, the number of women involved in art in Ukraine has grown steadily. The key names of the newest history of art include the participants of the New Wave Valeria Trubina and Natalya Filonenko; the central representative of the art of the 1990-2000s Marina Skugareva; Vlada Ralko, who appeared on the art scene in the first half of 2000s; Masha Shubina and Alevtina Kazidze; the R.E.P. members Zhanna Kadyrova, Lada Nakonechna, and Ksenia Gnylytska; artists of the SOSka group Bella Logacheva and Anna Kriventsova; Yevhenia Belorusets, Alina Yakubenko, Alina Kleitman, Anna Zvyagintseva, Lyubov Malikova, Maria Kulikovska, Daria Koltsova, Alina Kopytsa, Nina Murashka, Katya Yermolaeva, Antigone et al.

The Poetics of the Outland and the New Clubbing

The group of artists and creative people who started gathering in the Efir underground nightclub is another bright phenomenon in the post-Maidan Ukraine’s art. On the one hand, their programmatic hedonism, interest in the electronic music, active club life and general escapism serve as a counterweight to the country’s political preoccupations and conflicts. On the other hand, this very group of artists and activists, including Alina Yakubenko, Oleksandr Dolgyi, Yevhenia Molar, and Dana Brezhneva, formed an initiative to study the situation in the country’s Eastern regions and organized events in the most depressive regions suffering from the war.

The symbiosis of the rave spirit, which unexpectedly returned to Ukrainian art in the midst of a severe post-traumatic crisis, and acute political meanings, is perhaps the most characteristic feature of the second half of the 2010s. Perhaps, the most renowned project authored by this group is the long-term creative initiative DE NE DE[13]. A central figure of this project is an activist Yevhenia Molyar who examined the Soviet mosaics phenomenon and monumental art in Ukraine. DE NE DE focused on the contraversions of decommunization – the project of the post-Maidan government and its main ideologist – a right-wing historian Volodymyr Viatrovych. The purpose of decommunization was a final destruction of the monuments of the Soviet era in Ukraine. Artists came together to rethink the legacy of Soviet modernism and oppose the barbaric methods of the zealots of the radical memory politics.

At the height of the crisis in the east of the country, Yevhenia Molyar, together with the activists from the Ukrainian Crisis Media Centre Leonid Marushchak and Olha Gonchar, started organizing educational conferences and expeditions to the front-line zones. These initiatives, thanks to which Kyiv artists began visiting regularly small peripheral towns of eastern Ukraine, unexpectedly became the main point of attraction for creative people. Ukrainian art experienced a regional boom. The second half of the 2010s was the rediscovery of the outlands and the melancholic poetics of abandoned small local institutions and museums. The first DE NE DE exhibition opened in 2016 at the Flying Saucer building in Kyiv. The significant project of the initiative was the exposition The Museum of the City of Svitlohrad in the Lysychansk Local History Museum (2017). Another project of DE NE DE activists – the Above God (Над Богом) art residence, which has been taking place in Vinnytsia in the building of the half-abandoned Rossia cinema since 2015.

During the regional boom, in 2017, Vova Vorotniov hold a performance, which took more than a month – he walked on foot from his native miner town of Chervonohrad in the Lviv region to the east of the country, to the miner town of Lysychansk, located on the border with the military conflict zone. Substantially, the purpose of this trip was to transfer a piece of Chervonohrad coal to the collection of the Lysychansk Local History Museum. A simple gesture with a hint at the symmetry of the “poles” of Ukraine was supposed to unite symbolically two different parts of the country. The travelogue the artist has been publishing on social media along the way is a self-sufficient and interesting part of the project.

Vova Vorotniov. Documentation of Za/S xid project, 2017

Another popular initiative in the mid-2010s was related to the rave movement. These included art projects organized at the main hub of Kyiv electronic culture – the Closer club. The development of the underground club scene in the capital and numerous mini-raves in the country with the participation of artists gave rise to a number of artworks related to the new Ukrainian rave movement. This aesthetic is close to the “hipster” photography of the late 2000s – early 2010s. The main emphasis was placed on trash, second-hand, rejection of the idea to seem more civilized than it actually is, and, conversely, an accentuation on the vibrations of the “wild, wild East.” A symptomatic project of these times is a musical collaboration of the artist Anatoly Belov and DJ Gosha Babansky Lyudska podoba. His cinematic experiments – the film Tabun (2016) and the series REGLAMENT (2017) shot on the iPhone – Gosha Babansky closely documented the life of the new Kyiv underground. Of no less interest is the semi-documentary / semi-fiction film by Anatoly Belov and Oksana Kazmina about vampire ravers in Kyiv, The Feast of Life (Праздник жизни, 2016).

Anatoliy Belov, Fragment from a musical film Sex, Medicamentary, Rock’n’roll, 2013. Photograph provided by the PinchukArtCentre. Photographed by Sergey Illin

CXEMA party is the key phenomenon of the Ukrainian rave scene, thanks to which Kyiv in the late 2010s became the famous centre of the world electronic music.[14] Sasha Kurmaz`s Paradise project (2017) is a study of visitors of this event. In 2018, young directors Yarema Malashchuk and Roman Himey, who work at the intersection of cinema and contemporary art, had shot the Documenting CXEMA mini-film about this iconic party.

Forward to the past. Time to think retrospectively

Decommunization and related contraversive moments are the principal subject of the latest Ukrainian art. The preservation of Soviet mosaics, which the country’s leadership tried to destroy under the guise of a struggle with the ideological symbols of the totalitarian past, became a unifying factor. The book Decommunized: Ukrainian Soviet Mosaics[15] released in 2017 by the photographer Yevhen Nikiforov was a result of a major study of mosaics. Nikiforov’s second series, On the Monuments of the Republic, is devoted to contraversions of dismantling and destruction of Soviet monuments. Peripheral subjects and forgotten pages of history are in the focus of attention of the artists and activists’ community, whose interest in a memory issues by Nikita Kadan is defined by the umbrella term of “historiographic turn.”[16] By the end of the decade, the artist himself creates works on the theme of axial traumas of the twentieth century – Stalinist repressions, Jewish pogroms, etc. The mechanisms of memory and the difficulties of their functioning are developed in the Yevhenia Belorusets`s project Let’s Assemble Lenin’s Head (Соберем голову Ленина, 2015) at the PinchukArtCenre, as well as in the David Chichkan`s graphic art. In August 2017, in the former city of Kirovohrad, recently renamed to Kropyvnytskyi, Oleksiy Say made a witty statement about the repetition of historical failures. The rakes scattered around the pedestal of the former monument to Lenin, which the locals converted into an improvised memorial to the Maidan heroes, is perhaps the most relevant statement on anxieties and challenges of modern Ukraine.

At the end of the decade, museum becomes the point of intense interest. Since 2018, Oleksandr Roytburd has been managing the Odessa Fine Arts Museum. The community that arose around the initiative DE NE DE is grouped around a small but intriguing collection of Soviet art, which was amassed by the initiative collective farmer Yosyp Bukhanchuk during Soviet times in the village of Kmytiv not far from Kyiv.

A gaze turned back is a key feature of the optics of a number of art projects. In 2016, Mykola Ridnyi created the film Gray Horses (Сірі коні), which was dedicated to the story of his great-grandfather, an anarchist who fought on the side of Nestor Makhno at the beginning of the 20th century. Oleksiy Radinsky has been working for several years on the study of the works of Florian Yuriev, one of the Sixtiers. Radinsky`s film Facade Colour: Blue (Колір фасаду: синій) was premiered in 2019. The documentary tells about the construction of a new shopping mall next door to the Flying Saucer, the building designed by Yuriev in 1970s. The collapsing Soviet modernist building, surrounded by the unsightly chaos of the new development, is a sort of symbol of the cultural situation of Kyiv, with its rapidly degrading contemporaneity that is pushing artists to mythologize the sunken Atlantis of the Soviet project. Oleksiy Radinsky calls the late Soviet modernism “our antiquity.” Indeed, choosing between the mythology of a dying modernist empire and the hopeless life in a third world country, many artists are inclined to the first one. The disappointment in the progress and the unspoken traumas of the twentieth century lead to the fixation on history.

The farther the ghosts of the unspoken past move away in time, the more they torture us. A shining example is the war of memory politics that has erupted recently in Ukraine and around the world. Contemporary people, with all their gadgets, big data, and artificial intelligence, are becoming increasingly vulnerable to history issues. At the beginning of the twentieth century, the future was the deity of the avant-garde. The fetish of modern Ukrainian artists is the past. Probably, only having it thoroughly articulated, we would finally be free to look at the present.

[1] Yevgenia Belorusets. The Exhibition Before the Execution: Part One. https://archive.prostory.net.ua/ua/art/615–l–r—

[2] Barbican is a defensive outwork of medieval fortifications designed to protect the city gates.

[3] Ihor Gusev. LikeHokku 2013-2015. Dymchuk Gallery, 2015.

[4] Rebecca Schmid. Virtual Reality Asserts Itself as an Art Form in Its Own Right. The New York Times, May 1, 2018.

[5] Since 2014, the regular members of the group are Yuri Biley, Pavlo Kovach, Stanislav Turina, and Anton Varga. Open Group. About us. http://open-group.org.ua/ukr/about-us

[6] Open Archive: http://openarchive.com.ua/

[7] Mriya (“dream” in Ukrainian) is the largest cargo plane in the world, AN-225.

[8] Method Fond: https://sites.google.com/site/methodfund/

[9] Read more: Yevhenia Belorusets. On the work of Mykola Karabinovych, The Voice of Subtle Silence. Prostory, March 29, 2018, https://prostory.net.ua/ua/krytyka/321-o-rabote-nikolaya-karabinovicha-golos-tonkoj-tishiny

[10] For more information about women in Ukrainian art, see Why There Are Great Female Artists in Ukrainian Art. (Чому в українському мистецтві є великі художниці) PinchukArtCentre, 2019

[11] Kateryna Yakovlenko. Medusa’s Mouth. The First Attempts of Feminist Exhibitions (Катерина Яковленко. «Рот медузи»: перші спроби феміністичних виставок). Korydor, Nov. 9 2018

[12] Oksana Bryukhovetska. Image of victim and emansipation. An Essay on Ukrainian Art Scene and Feminism. (Оксана Брюховецька. Образ жертви і емансипація. Нарис про українську арт-сцену і фемінізм). Prostory, March 3, 2017

[13] De ne de is “here and there” in Ukrainian.

[14] Kate Villevoye. Lose yourself in the new sound of Kiev. i-D magazine, 31 May, 2016.

[15] Yevhen Nikiforov. Decommunized: Ukrainian Soviet Mosaics. Kyiv: Osnovy Publishing, 2017.

[16] Nikita Kadan. In Place of Memory (Никита Кадан. На месте памяти). Художественный журнал, №104, 2018. The historiographic turn in art has been described by American art critic and curator Dieter Roelstraete in the late 2000s. Read more: Dieter Roelstraete. After the Historiographic Turn: Current Findings. e-flux Journal #06 – May 2009.