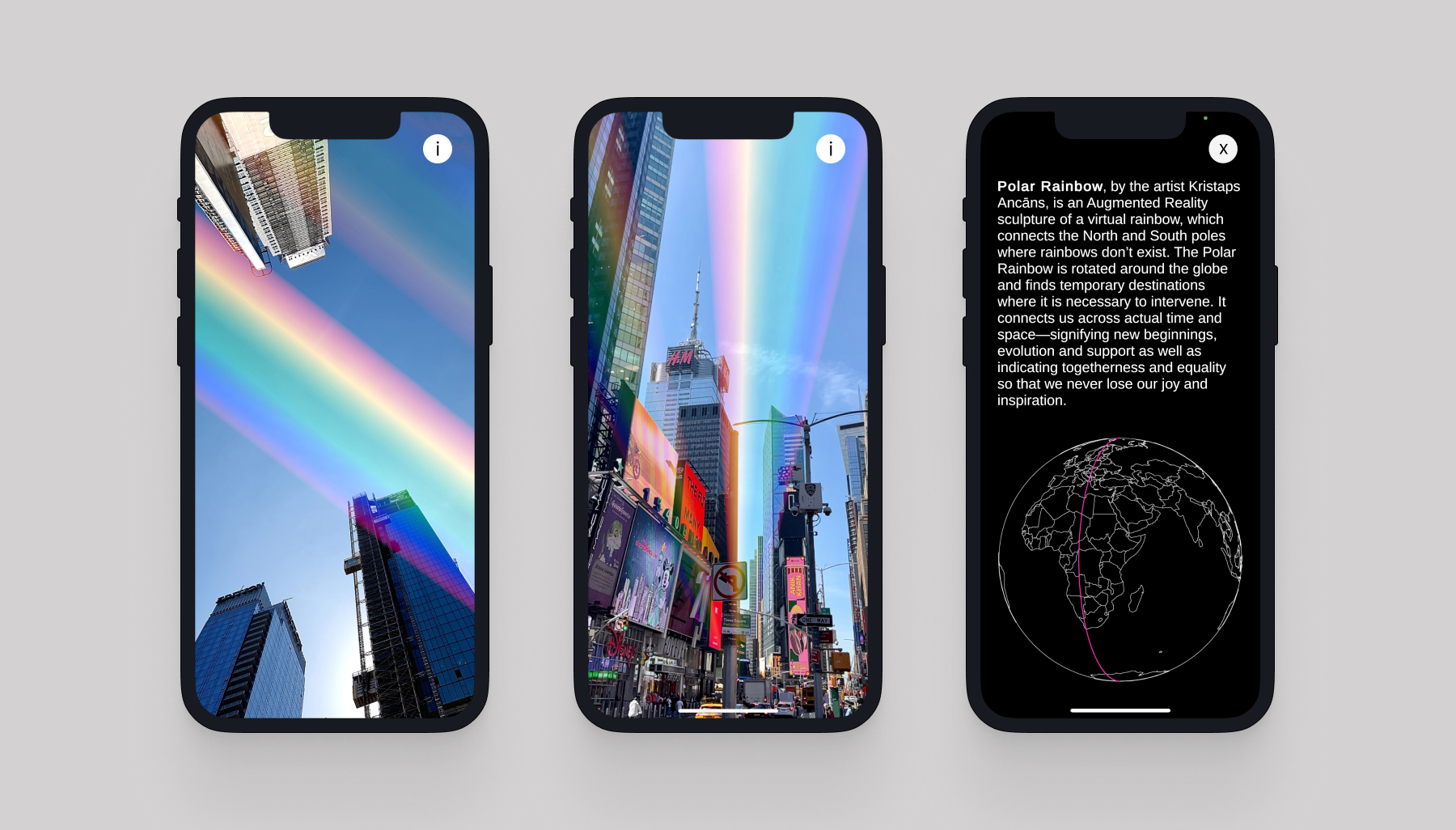

Polar Rainbow by Latvian-born artist Kristaps Ancāns is currently on view in Warsaw, along the 21E meridian line, following its premiere as part of the Times Square Arts’ public art series in honor of Pride Month in New York City where it was positioned along the 74W meridian. Subsequent editions will be unveiled in the following months internationally, including the Baltic states and other politically and socially significant meridian lines. The augmented reality app, developed by Ancāns in collaboration with the data visualization studio Platvorm, is designed to project a rainbow that connects the North and South poles in certain locations, attempting to reflect on memory and imagination, opening a debate on the role of digital technologies and agency in today’s divided world. For each iteration of the project, Ancāns and curator Corina L. Apostol have partnered with international human rights organizations, arts institutions, and various groups advocating for LGBTQIA+ rights to promote the app in communities geographically located along the meridian line where the digital rainbow appears.

Nine Rays of Light in the Sky, also known as Unlimited Vertical Composition [Kompozycja pionowa nieograniczona], by Henryk Stażewski, originally displayed on the 9th of May 1970 on the occasion of the Sympozjum Plastyczne Wrocław ‘70. The image depicts the re-creation of Stażewski’s project on Debember 9th, 2008. Photo: Bartosz Stawiarski. Image courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw

In the last several days I have used the new app Polar Rainbow, pausing my strolls or bike rides every now and then to see how well-known spots and landmarks appear through the app’s lens. I truly enjoyed this experience, which has reminded me of other rainbow-inspired site-specific public works that have appeared in Poland, such as Nine Rays of Light in the Sky (1970) by Henryk Stażewski, one the most significant projects of this brilliant artist. The colored light beams were pointed upwards, coming from spotlights located close to the ground, creating an unexpected, colorful composition of lines that gently reached out to the sky for nearly one and a half hours. Stażewski himself mentioned that his work could become a permanent illumination for Wrocław, assembled and activated during important events. The abstract light “painting” was recreated by the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw in 2008, to mark the first of a series of public space interventions carried out in the vicinity of the Museum’s permanent building, close to Parade Square in front of Warsaw’s Palace of Culture and Science[1]. I can’t help but think of the painter wearing his rainbow-painted slippers in his studio and the careful and thoughtful way he used colors in his work which today, could be interpreted so differently.

Polar Rainbow was created by Kristaps Ancāns as an imaginary rainbow to be launched in different locations, especially those where queer communities are questioned and threatened — “signifying new beginnings, evolution and support as well as indicating togetherness and equality so that we never lose our joy and inspiration” (as we read in the app’s “Info” tab). In New York City, the app was visible over Times Square, which for many years since the Stonewall riots, has been the site of both protest and celebration for LGBTQIA+ rights. The double rainbow by Ancāns stretched between the two poles along the 74W meridian line — the most populous meridian in the Americas, including locations in Canada, the US, the Bahamas, Colombia, Peru and Chile. In Warsaw on the other hand, the artist’s digital sculpture is visible almost anywhere around the city, especially near Theatre Square in the capital’s historic center. For several years now, Warsaw as a capital city has been a haven for non-heteronormative Polish communities, and is often where the country’s biggest celebrations and protests occur. This year marked more than two decades of Warsaw’s “Equality Parade” (“Parada Równości”[2]), as it’s known locally, organized as a yearly gathering by the LGBTQIA+ community since 2001. It was called off only once in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. In response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the 2022 edition of the Parade was a host for its Ukrainian counterpart, KyivPride. The event in the capital city has numerous sister events — referred to as “Equality Marches” — in smaller cities across the country.

Yet despite the parades and celebration, and the haven for artist communities and cultural institutions that Warsaw provides, a conservative movement has swept the country and the LGBTQIA+ community, along with other marginalized communities, continue to struggle for legal visibility and broader social acceptance. Poland’s consevative legislation, the hesitation to acknowledge the presence of queer or non-heteronormative folks, and transphobic views expressed by politicians, among others, are well-known facts. The right-wing ruling party aims to repress and control those who either don’t conform to traditional categories of gender or those who are openly liberal and anti-catholic. In fact, in 2020, several small towns and regions primarily in the Southern and Eastern parts of Poland declared themselves “LGBT-free zones”. As a consequence, the European Commission introduced financial sanctions against these discriminatory laws and so many regions eventually, and begrudgingly, backed out of their original plans.

Image taken in front of the National Museum in Warsaw in 2019, in protest of the censorship of artworks by prominent female Polish artists, including Natalia LL. The bananas reference her work “Consumer Art” which was one of the works removed from view. Image courtesy of Aleksander Hudzik

Earlier this year the Polish parliament approved a law banning LGBTQIA+ inclusive education in schools, a situation similar to the one in Hungary, where the law introduced to prohibit schools from teaching LGBT-related content passed a year earlier. And it’s not only about queer rights, as Poland is a country where women’s rights have been openly violated by the country’s abortion bans, causing massive world-wide protests. Public art institutions have also now become tools for boosting the ruling party’s aspirations to impose “traditional values” on Polish citizens. One notable example occurred in spring 2019 at the National Museum in Warsaw, where Jerzy Miziołek, the previous director of the institution, closed the permanent gallery of 20th and 21st century art (which had been a successfully functioning focal point of the museum for several years). The reason behind this decision was the allegedly explicit content authored by Poland’s most iconic female artists Natalia LL, Katarzyna Kozyra, and the duo “Grupa Sędzia Główny”. In response, crowds gathered in front of the museum to eat bananas, directly referencing the censored work by Natalia LL from the Consumer Art series. It’s important to note that this conservative swing is quite aggressive and unprecedented. For example, if we look at the programming of the same museum from just over a decade ago, in 2010 the National Museum organized and hosted a now-historic, comprehensive, queer-themed exhibition called Ars Homo Erotica. This exhibition transformed the biggest Polish museum into a platform for queer visibility by bringing together hundreds of objects showcasing homoerotic content from antiquity to the present.

Kristaps Ancāns, How do you help a butterfly with wet wings? (2021). Exhibition view: Publiek Park, Young Friends of S.M.A.K. museum, Ghent (1–4 July 2021). Courtesy the artist. Photo by Kristaps Ancāns

“Have we all learned how to be human at home?” — a question Kristaps Ancāns asked in 2021 provoked lively debates both online and offline. A sculptural installation in steel arched over the threshold of Domobaal Gallery in London, where it was initially shown, met a number of reactions from viewers, asking them to reconsider their private spaces of confinement during the pandemic crisis “fueling uncertainty and speculation”[3]. Ancāns’s work spans installation, sculpture, language and moving images, exploring the confusing relationship between humans, nature and machines through an evolving conceptual game with its own artificial intelligence. As he puts in his statement, the installations he creates “welcome questioning, invite uncertainty in their relationship with the viewer”. Last year, in Citadel Park in Ghent, on the invitation of S.M.A.K Museum, Ancāns created a banner which was draped above the gatehouse near the museum building. The artist used black lettering against a white background, enlarging it to the size of a long billboard which read “How do you help a butterfly with wet wings?”, with the “How” crossed out. An added handwritten line allowed for a different reading: “Do you help a butterfly with wet wings?” which both brought forward the hidden use of the park as a cruising area while commenting on the simultaneous “fragility and resilience” of queer communities.

Returning to Poland, and the significance of Ancāns’s work in this place, it is important to also acknowledge the transphobia that plague’s this country. In May 2019 the non-binary transgender activist Milo Mazurkiewicz took their own life by jumping from a bridge into the Vistula river in Warsaw, leaving a letter in which they declared being misunderstood by their doctors. Since then, Milo has become a heroine for many protesters and initiatives in defense of trans rights. One of the better-known collectives is Stop Bzdurom (stop nonsense), who actively fights against LGBTQIA+ disinformation in Poland. In August 2020, its leading member Margot Szutowicz, a 24-year-old nonbinary queer activist, was placed in pretrial detention provoking a wave of protests, and numerous detentions of other people in August 2020[4]. “Ain’t nothing good about being detained by the police. It’s a risk that many people decide to take due to their activist gestures. I don’t think that anyone who took part in the protests on August 7th, 2019 in defense of Margot, expected that they would need to take this risk[5]. 48 persons were detained and today the court confirms that these detains were for the most part illegal, illegitimate or injust”, wrote Karolina Gierdal, an attorney dedicated to legal assistance issues against the discriminaion who has been associated with the Campaign Against Homophobia (from Karolina Gierdal, Gazeta Strajkowa, #4, 2021[6]). The above mentioned events in these past years resonate with the active scene of artists openly touching upon queer issues in Poland — namely Karol Radziszewski’s multidimensional artistic and archivist practice commenting on the past and present of queer communities in Central and Eastern European countries, Daniel Rycharski’s rural activism in his home village of Kurówko in Mazovia where he engages with the local community as he reconciles his queerness alongside his faith, Katarzyna Perlak’s works in moving image and performance, among others, driven by politics and queer subjectivities, Wojciech Puś — queer artist and filmmaker whose long-term project Endless is a collage of images, light, and sound features a number of bodies “in process”, Mikołaj Sobczak’s paintings and performative works reflecting on nearly forgotten queer protagonists from the past, or Liliana Zeic’s focus on social issues perceived from a perspective of radical care, touching upon non-heteronormative and queer positions — to name just a few.

But what’s to fear in a rainbow? Ancāns’s ephemeral project is a digital installation of a multicolored arc, normally observed in the sky when rays of light intensely illuminate tiny water drops of condensed air. It can also be interpreted as a “digital postcard” soaring over the city of Warsaw. In order to witness it, you need to download the Polar Rainbow app. “Stretching across the 21E meridian from the North Pole to South Pole, this virtual double rainbow symbolizes solidarity with LGBTQIA+ communities around the world”, as we read in the press release posted on Facebook[7]. A number of international organizations, including Biblioteka Azyl (PL), Homokomando (PL), Longyearbyen Pride (NO), Magyar LMBT Szövetség – Hungarian LGBT Alliance (HU), Mozaīka (LV), Nacionalinė LGBT* teisių organizacija /Lithuanian Gay League (LT), Positive Voice (GR), Pride Shelter Trust (SA), Rainbow School (GR), joined forces to help spread information about the presence of the work here to “intervene in regions where human rights are at risk”. In addition to solidarity with the LGBTQIA+ community, the concept for the project refers to the peaceful political demonstration that occurred on August 23, 1989 dubbed “The Baltic Way”, when approximately two million people from Vilnius to Tallinn manifested their solidarity in their quest for independence by joining their hands and forming a 600 km long “human chain”. This reference becomes especially meaningful when we think of Poland, a country neighboring the Baltic states.

Although Kristaps Ancāns’s work is for the most part interdisciplinary, many of his projects — Polar Rainbow included — evoke the artist’s formal education in painting, which began prior to his studies at Central Saint Martins in London where he developed his artistic voice after graduating from the Art Academy of Latvia. His references to artificial intelligence or speculation leave space for viewers’ interpretation — both notes visible in Polar Rainbow. Given its digital character, Polar Rainbow is also somewhat of a commentary on how little has actually changed in the physical landscape, in terms of legal action, even though non-heteronormative communities have been fighting to be seen for years. The ongoing debate over subjectivity and agency in LGBTQIA+ causes was also reflected in Julita Wójcik’s Rainbow, which many people across Europe recognise without hesitation and associate it with Warsaw. The original version of Wójcik’s sculptural work stood next to the Dom Pracy Twórczej (Creative Work House) in Wigry in 2010. From 2011 to 2012, the artwork was placed in front of the European Parliament building in Brussels and then finally, in June 2013, the steel construction, with thousands of artificial flowers, appeared in Saviour Square and stood there until it was dismantled three years later. The universal message that accompanied the project referred to the symbolism of biblical Covenants[8]. Unfortunately not everyone liked it — the rainbow was set on fire seven times in the first year that it was installed in Saviour Square. Since then, nothing else has appeared on Saviour Square that could replace this strong visual, characteristic symbol of peace. The history of the rainbow is practically always alive in Warsaw, and plans to recreate different versions in different spaces across the city have been discussed on several occasions. We thought we might finally be seeing Wójcik’s Rainbow again thanks to the efforts of the members of Homokomando Association, which initiated a call for the creation of a new architectural and artistic rainbow-based project. However we have just learned that the city of Warsaw did not approve this project in their civic budget.

In 2017, the Zachęta National Gallery of Art in Warsaw presented Angel Rainbow, a meaningful title for the exhibition showing the works of Paris-based Armenian conceptual artist Sarkis Zabunyan. His signature neon arc was featured in a number of his previous exhibitions — “The whole world needs a rainbow”, as the artist claimed[9]. And for the past three years, that same institution has hosted yet another work in dialogue with Julita Wójcik’s eminent work which has contributed to Warsaw’s landscape of public art. The angular, frame-like rainbow sitting in front of the facade of the Zachęta is a remake of Marek Sobczyk’s installation entitled Simple Rainbow which stood in the same place from 1991 to 1993, when the artist desired to evoke biblical symbols of understanding. The original rainbow was made of hand-painted boards, whereas the contemporary one, erected in 2019, was made in accordance with today’s regulations and technology to be durable and resistant to fire. And it’s also the Zachęta where the artificial flowers were assembled and prepared for the Brussels edition of Julita Wójcik’s work. But, again we need to temper our celebration as Simple Rainbow by Sobczyk will no longer remain in front of the Zachęta, following the decision taken by Janusz Janowski, the new right-wing director of the institution[10]. It was taken down on Tuesday, July 18th. We no longer need fire to burn rainbows, politics seems to be enough.

Perhaps in line with its ephemeral nature, it seems that it’s difficult to preserve the sight of a rainbow for any length of time. I am reminded of Hans Memling’s triptych “The Last Judgment” from the 15th century, which can be seen at the National Museum in Gdańsk. The painting depicts a triumphant Jesus Christ seated upon a vast, majestic multicolored arc. This work — labeled as one of Poland’s national treasures — where once more, a rainbow plays a prominent role, is another reference that adds a deeper context to Ancāns’s work.

“For people who are full of hatred the rainbow may be seen even as a weapon. I don’t think I need to mention dictator Putin who stated that one of the reasons for the Ukrainian war is the LGBTQI+ community; people in Russia have been hunted down and have disappeared already in certain areas even before the war started. I always say that there needs to be a distinction between religion and the institution who appoints themselves to regulate human belief like the catholic church in Poland, Latvia or other places. This reminds me of the self-appointed Belarusian president Alexander Lukashenko” — states Ancāns (…)

Remembering his visit to Warsaw, the artist says further: “We visited the Opatrzności Bożej church in Warsaw and I can say clearly that I don’t think God hates rainbows and any of its representations – when we were looking where the Polar Rainbow crosses inside the building a miracle happened: next to digital rainbow appeared a natural double rainbow in the church (…)”

Edited by Ewa Borysiewicz and Katie Zazenski

[1]Nine Rays of Light in the Sky, also known as Unlimited Vertical Composition [Kompozycja pionowa nieograniczona] was an installation by Henryk Stażewski originally displayed on the 9th of May 1970 on the occasion of the Sympozjum Plastyczne Wrocław ‘70. The Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw recreated this work on Dec 5th, 2008. See: https://artmuseum.pl/en/wystawy/henryk-stazewski-dziewiec-promieni-swiatla-na-niebie.

[2] https://www.paradarownosci.eu/en/homepage/

[3]The piece was to be delivered this year as a gift to the Embassy of Russia in London, and alas it could not be received. See the text by Corina L. Apostol from the artist’s website, https://www.kristapsancans.com.

[4] See: https://stopbzdurom.pl/.

[5]See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Margot_(activist).

[6] From the Archive of Public Protests’s “Gazeta Strajkowa” (Strike Newspaper) #4, https://archiwumprotestow.pl/app/uploads/2021/06/app4-web-s.pdf.

[7] https://www.facebook.com/events/766090897752668.

[8]Biblical Covenants acted as legally-binding documents.

[9] Cały świat potrzebuje tęczy, “Rzeczpospolita”, 20.01.2018, https://www.rp.pl/rzezba/art9975321-caly-swiat-potrzebuje-teczy.

[10]Janusz Janowski, a painter who turned director without a competition from the Ministry of Culture earlier this year, replacing the acclaimed art historian and curator Hanna Wróblewska.

Imprint

| Artist | Kristaps Ancāns |

| Curated by | Corina L. Apostol |

| Index | Corina L. Apostol Kristaps Ancāns Polar Rainbow Romuald Demidenko |