Dorian Batycka: You recently won one of the most important awards in Germany, the Preis der Nationalgalerie. Immediately after receiving the award, you published an open-letter together with the other shortlisted nominees (Sol Calero, Iman Issa, Jumana Manna) questioning the competition’s policy for their lack of financial compension and for focusing too heavily on the gender of the nominees. Why did you choose to do so and has there been any reply from the prize committee?

Agnieszka Polska: I think our statement pretty accurately described the situation we were in. After the exhibition opened at the Hamburger Bahnhof we started an email exchange with the competition officials stressing that we saw the lack of artist honorariums as a problem. We reckoned that the lack of remunerations reflected the dangerous mindset according to which a promise of future recognisability can substitute paying someone for the work he or she is doing. Later, we added our criticisms about the way we were introduced in press releases and at the award ceremony. We felt we were being infantilized because of the never-ending emphasis on our gender. The fact that there were only female participants within the competition was turned into a proof of the supposed progressiveness of the event. I too was glad I could be there among all those female artists. Still, I’d rather value them on the basis of their innovative approach to art, the boldness of their political expression, or ability to work with space, not because of the mere fact they are women. Marginalization of women in the art world is, indeed, an issue. It’s good that there are more situations where the participant’s sex is not relevant. We will not, however, solve the problem by labeling these isolated events with all-female participants as “woman’s exhibition.”

Were there different drafts of the letter? Why did you decide to publish an open-letter instead of voicing your concenrs with the prize committee privately?

At a certain stage of our exchange with the officials, we came to the conclusion that since our problems were describing a wider characteristic within many other cultural events, that our statement should take the form of an open letter. There is a growing number of events, exhibitions and competitions that, I believe, should be described as spectacle designed by neoliberal forces. The work writing the letter was very time-consuming. its final version being a sum of numerous rough drafts. At the same time, working on the letter with Sol, Jumana and Iman was a very rewarding experience. I think that, in a way, we managed to substitute the expected competitiveness of the event with cooperation.

Since the letter was published, we’ve stayed in touch with the competition officials. The release of our statement has not at all impacted my preparations for the exhibition at Hamburger Bahnhof, which takes place next autumn. I would also like to stress that despite the problems I listed before with regards to cooperation with the institution, I was, just like the other artists, satisfied with our presentations during the exhibition at the Hamburger Bahnof.

In 2014, along with a number of other artists you chose to withdraw from the Biennale of Sydney because of the event’s ties to Transfield Holdings, a company with financial interests in forcible internment camps for people seeking asylum in Australia. Can you talk about the difference between these situations? And when it makes sense to write an open-letter, versus when it makes sense to openly boycott?

First, let me say that those two situations are not really comparable. In the case of the Preis der Nationalgalerie, our criticisms were aimed at problems symptomatic of many branches of culture, problems that occurred in the course of the generally satisfying cooperation with the institution.

In 2014 in Sydney, on the other hand, our aim was to protest against the cultural institution’s financial links with a company that administered two forcible internment camps where refugees who arrive in Australia without visas are kept for an indefinite amount of time. “Indefinite” in this case usually means years: long-term confinement inside closed and overcrowded compounds with very poor sanitary standards, and without much hope for any change.

A problem that repeatedly arises during exhibition-related protests is the issue of their efficiency, not just within artistic circles, but also outside. What should we do, so the protests can do more than just soothe our conscience?

But in Sydney you were successful, in the sense that the Biennale cut ties with Transfield.

The purpose of our withdrawal was to put officials under direct pressure so that they gave up collaboration with Transfield. The indirect aim was to achieve some media coverage in order to alert both the Australian and the international public about human-right-infringing practices. Following the release of the open letter, signed by several dozen artists, repeated protests from a number of other organizations, and eventually the withdrawal of nine artists from the Biennale, Luca Belgiorno-Nettis, general manager at Transfield Holdings, resigned as chairman of the Biennale board. After his decision some of the protesters, including myself, chose to resume participation in the event. Since there are still cases of cooperation between the cultural sector and companies involved in the forcible detainment of refugees, there are also artists who continue to protest this. Now, for example, there is an ongoing protest in Australia against ties between the Gallery of Victoria and Wilson Security. I think that each situation is unique, requiring different reactions. Luckily, there’s not a single practice or pattern here. A problem that repeatedly arises during exhibition-related protests is the issue of their efficiency, not just within artistic circles, but also outside. What should we do, so the protests can do more than just soothe our conscience?

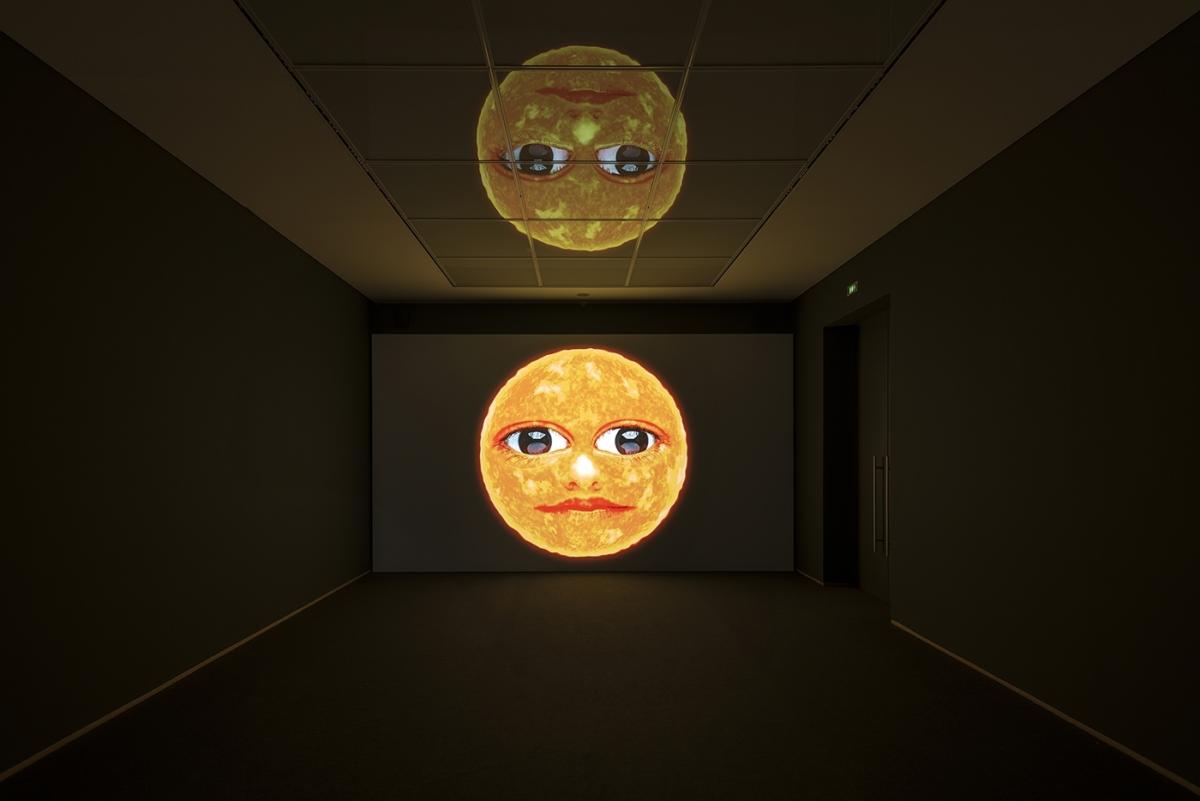

Agnieszka Polska: What the Sun Has Seen (Version II), 2017 | Installationsansicht Hamburger Bahnhof – Museum für Gegenwart – Berlin | © Nationalgalerie – Staatliche Museen zu Berlin / Jan Windszus / Courtesy Zak Branicka Galerie, Berlin and OVERDUIN & CO., LA

Not only in Australia have cultural institutions encountered such problems. In Poland, especially now under PiS (Law and Justice), the role of politics in culture is becoming a major issue as the government has started using very hostile takeover measures of critical cultural institutions and the replacing with pro-PiS puppets. Case in point being the Director of the Polish Culture Institution in Berlin, who was fired in 2016 for programming “too much Jewish content.” In light of these troubling measures, what are your thoughts on the working conditions of artists active in Poland today?

So far, surprisingly enough, changes in art administration are not as painful as in the case of film and theatre. The unpleasant truth here may be the fact that visual arts barely impact public opinion, and therefore do not pose a threat to autocracy. However, it does seem like institutions presenting contemporary art in Poland are going to face more problems. And if they do not, this will mean a question mark against their very mission and efficiency. I am against attempts to dialogue with the pro-government circles. Also, in the current reality, I do not believe in the “march through the institutions” strategy. It is very likely that the very fact that film and theatre are now being deprived of their institutions will result in a shift towards more progressive forms of activity. Visual arts, in this respect, would then likely stay behind.

In your view, what are the most effective ways of mitigating what you describe as the “conquest of institutions”?

I’m under the impression that while the political opposition in Poland holds onto its self-proclaimed romantic image from the days of “Solidarity,” similarily many protest acts inside cultural circles seem as though they just came from the 1980s. They often seem to simply ignore changes that have taken place over the last thirty years. I think that, in a way, the most important mission within the field of art and politics is to get in touch with teenagers. Many of whom, brought up in an atmosphere of frustration by parents disappointed with the lack of wealth redistribution, are very susceptible to nationalistic influences. Obviously, to achieve any visible effects or change, years of work and new channels of communication will be needed. The initialization of such activities would, in reality, mean launching new and unconventional institutions ready to also operate in virtual space.

What about your recent work? Has your activism and political awarness integrated itself more visibly into your films?

I am finishing a feature-length film entitled Hurra! which portrays the dilemmas of artists trying to choose the best way of protest. In the film, we see a group of filmmakers, who represent something like a hipster-left, completing a movie about Rosa Luxemburg. At some point, they are visited by an old friend who’s now a member of a radical left-wing violence-applying organization modelled on the Red Army Faction. The woman demands that they return the money the organization had deposited with them. As it turns out, the money is gone, because it has all been spent on the Luxemburg project. And now, obviously enough, the filmmakers are in trouble. Their biggest problem, however, is the dilemma of where to draw the line with regards to political commitment and the efficiency of applied means.

My earlier works often combine a “documentary” layer within the text, supplemented with a number of visual stimuli, which are meant to put the audience in a state resembling a trance.

Interesting. In a way I’m reminded of earlier pioneers in art film and documentary like Harun Farocki, Chris Marker, Jeremy Shaw, Hito Steyerl, and even to a certain extent, Adam Curtis. Do you envisage yourself more as a ‘documentary’ filmmaker, or closer to an ‘art’ filmmaker?

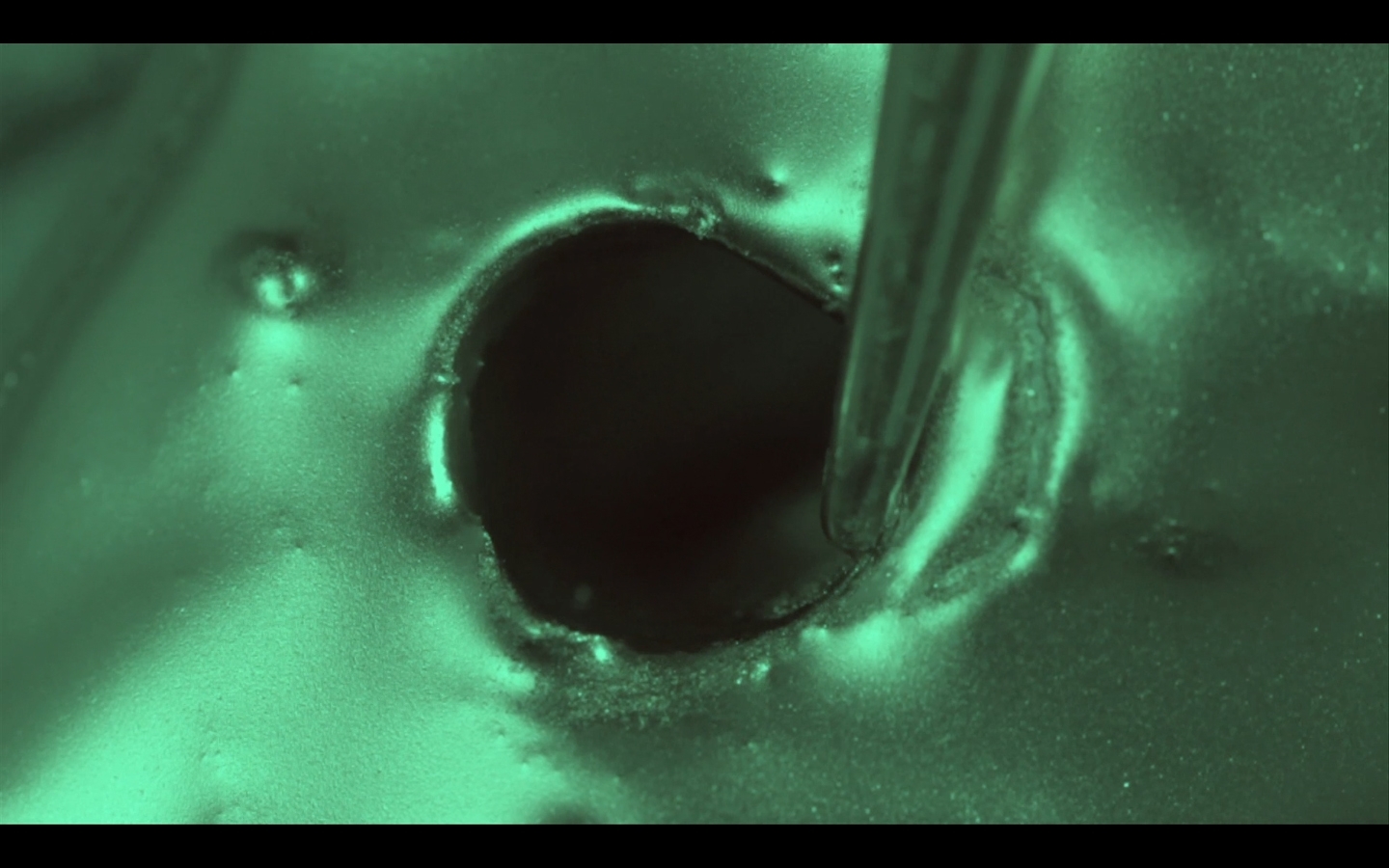

Many of my early works, to some extent, draw on the format of documentary, even though they depart from the format in obvious ways, too. In many cases, I took for a real story and try turning it into something surreal, an irony-based narrative, not always true to the facts. Quasi-documentaries are nowadays a rather obvious medium. Contemporary information recipient have affinity to quasi-documentaries rather than to documentaries. My earlier works often combine a “documentary” layer within the text, supplemented with a number of visual stimuli, which are meant to put the audience in a state resembling a trance. That is how, for example, Pistolety [Guns – eds.], an earlier film of mine, was made. It was a joint undertaking between Witek Orski and myself, referring to the story of a pistol disarming undertaken by authorities at the Museum of the Polish Military during a series of student protests in 1968. Fearing that the protesters could get ahold of weapons, in consequence, the barrels of all the exhibitis – pistols and rifles, including ones from the 17th century, were drilled-through. The entire visual layer of that film is just a series of multi-coloured rotating charts.

Agnieszka Polska, Witek Orski, “Pistolety” [“Guns”], 2014, HD video © artist, ŻAK | BRANICKA Gallery

So you’re actively trying to blend truth and fiction?

In my more recent works, I’ve given up on reality-based stories and turned towards fiction and science-fiction. I’m now focusing on how to work with audio and visual stimuli, which can influence the audience in a defined way. These works are based on the concept of introducing the audience to a state of immersion. This way of working with the stimuli can be found in New Sun, a film I’m now presenting at the Preis der Nationalgalerie exhibition. It consists of a half-sung poetic monologue of an anthropomorphic sun speaking to a lover. Such works, while addressing ecological disasters, together with the rise of nationalistic discourse, do not have an unequivocal political potential: one that could directly lead to change.

At the same time, I’ve started to perceive “immersion” itself as political potential of sorts. It is because it provides the possibility of creating an environment competitive to, i.e., the environment one can encounter in the church. Where mass becomes a combination of sounds and vocal monotony. I imagine a situation when an audience, after having visited a contemporary art exhibition, will no longer feel the need to go to a temple of an organized religion.

Imprint

| Artist | Jumana Manna, Sol Calero, Iman Issa, Agnieszka Polska |

| Exhibition | Preis der Nationalegalerie |

| Place / venue | Hamburger Bahnhof – Museum für Gegenwart – Berlin |

| Dates | September 29, 2017 – January 14, 2018 |

| Website | preisdernationalgalerie.de/en/ |

| Index | Agnieszka Polska Biennale of Sydney Dorian Batycka Hamburger Bahnhof Iman Issa Jumana Manna Sol Calero Transfield Holdings Witek Orski |