In the course of the Cold War, architects, planners, and construction companies from socialist Eastern Europe engaged in a vibrant collaboration with those in the Global South in order to bring modernization to the developing world. Architecture in Global Socialism, a new book by architectural historian Łukasz Stanek, shows how their collaboration reshaped five cities in West Africa and the Middle East: Accra, Lagos, Baghdad, Abu Dhabi, and Kuwait City.

Stanek describes how local authorities and professionals in these cities drew on Soviet prefabrication systems, Hungarian and Polish planning methods, Yugoslav and Bulgarian construction materials, Romanian and East German standard designs, and manual laborers from across Eastern Europe. Architecture in Global Socialism shows these interactions as part of what he calls socialist worldmaking, or practices of global cooperation that were sustained by socialist countries through institutional frameworks, political discourses, procedures of foreign trade, and everyday experiences of collaboration.

Socialist worldmaking included countries which aimed at the implementation of the socialist path of development, such as Ghana under the government of Kwame Nkrumah (1957-66). Working together with their Ghanaian counterparts, Soviet and Eastern European engineers, architects, and planners designed and built hundreds of buildings in the capital Accra and elsewhere in the country, from factories to housing projects, from public spaces to schools and hospitals. By contrast, governments in independent Nigeria did not pursue socialist development. By the 1970s, they welcomed Eastern European state enterprises as a means to stimulate economic competition between foreign investors and to fill the shortages in the professional workforce. Accordingly, Bulgarian, Hungarian, Polish, Romanian, and Yugoslav architects and planners working in Nigeria referred to longer historical experiences which they claimed to share with West Africans since the long 19th century, including the experience of nation building, economic modernisation, and cultural emancipation.

The motivations of socialist countries and their partners in Africa and Asia were shaped by geopolitical and economic shifts, such as the oil embargo of 1973. In the wake of the embargo and the debt crisis in Eastern Europe that followed, mercantile motivations for the mobility of design and construction services prevailed among decision-makers in socialist countries. Together with their counterparts they exploited such instruments of state-socialist political economy as barter. For example, governments in Baathist Iraq exchanged crude oil for industrial facilities, social amenities, housing projects, and master-planning services from Eastern Europe. By the last decade of the Cold War, these experiences facilitated the entrance of several state-socialist companies and architects into the increasingly globalized market of contractors and designers in the Middle East and elsewhere.

By mapping these geographies of collaboration, Architecture in Global Socialism shows that urbanization and its architecture in the global South can be reduced neither to the consequence of the colonial encounter with Western Europe nor to the impact of global capitalism. This book presents a new understanding of global urbanization through the lens of socialist internationalism, thus challenging long-held notions about architecture, modernization, and development in the Global South.

***

Epilogue and Outlook

from the book ‘Architecture in Global Socialism: Eastern Europe, West Africa, and the Middle East in the Cold War’

Many of the interviews for this book took place in the homes of its protagonists. Quite often, these were sizable detached houses, located in suburbs of Belgrade, Bucharest, Budapest, Prague, Sofia, Warsaw, and Wrocław. Districts of such individual houses added up to new patterns of urbanization emerging since the 1970s at the peripheries of Eastern European cities. I was told several times by my interviewees that “this house was paid for by [their] work on export projects.” This suggests that suburbanization in Eastern Europe during the Cold War needs to be understood through the lens of decolonization and the subsequent cooperation between the developing countries and the Comecon that resulted not only in the remittances sent home, but also in other flows: crude oil bartered for export projects, expertise and technologies acquired on construction sites abroad, and consumption patterns interiorized when living in foreign countries.

This is one of the possible lines of research that could follow from this book. Initiated as a contribution to the historiography of twentieth-century architecture, its first step was to reverse the research focus on architectural mobilities from their points of departure in the Global North to their points of deployment in the Global South. From such a recalibrated perspective, this book challenged capitalist triumphalism that, in the wake of the Cold War, reduced architecture’s globalization to Westernization or Americanization, and retroactively extended these narratives into a teleological development path of architecture after World War II. Against the Cold War propaganda and its afterlives, the preceding chapters showed that West African and Middle Eastern countries were no Soviet “proxies” or “pawns,” and neither was Eastern Europe a homogenous “Soviet bloc.” Rather, the view from the South allowed showing how architectures coproduced by Eastern Europeans, West Africans, and Middle Easterners were part of complex and uneven negotiations between parties with different and evolving geopolitical ambitions, state-building aims, economic motivation, and cultural agendas.

This vantage point from the South contributes to the current effort of historians of modernism by showing that modern architecture’s worldwide emergence was a fundamentally antagonistic and heterogeneous process, informed by competing visions of global collaboration in the Cold War. When seen from West Africa and the Middle East, modern architecture appears as always-already on the move, and its history is that of resources circulating at various scales and with various speeds, their capturing and appropriation. This appropriation included a reactivation of the modern movement’s “other” traditions, in particular Central European, but also contributions from countries that have been less studied by architectural historians, such as Bulgaria and Romania. New types of institutions were instrumental in this process, including foreign trade organizations in Eastern Europe and municipal planners and state contractors in West Africa and the Middle East. The process of revising, challenging, and abandoning modern architecture was equally heterogeneous, and among its many sources was the encounter between the experience of “real existing modernism” in Eastern Europe with an equally disappointing experience of post-oil urbanization in parts of Asia and Africa.

The preceding mapping of architectural collaboration between Eastern Europeans, West Africans, and Middle Easterners did not start with a normative definition of what architecture is but rather with a nominalist study of what architects did as architects. Such an ostensibly limited entrance point revealed that the deployment of architectural labor on export contracts was not restricted to design work but included also construction management, supervision, administration, legislation, teaching, and research. The preceding chapters studied these engagements in specific locations: state design institutes and private architectural practices, construction sites, municipalities and ministries, and architectural schools and research centers. The review of such deployments showed that architectural labor often traveled as part of larger packages: aggregated with other types of labor, including that of planners, engineers, technicians, managers, scholars, and workers, and associated with other things. They included Soviet prefabrication systems and machinery, Bulgarian engineering tables and building materials, East German type designs and legislation schemes, Hungarian planning concepts and research methodologies, Polish conservation methods and drawing techniques, Romanian design guidelines and seismic norms, Czechoslovak teaching curricula, Croatian façade systems, Slovenian furniture, and Serbian steel. The architects’ job was not just to bring these things to their destinations but also to manipulate them in order to adjust their performances to the conditions on site or, by contrast, to maintain their original performance in the new locations.

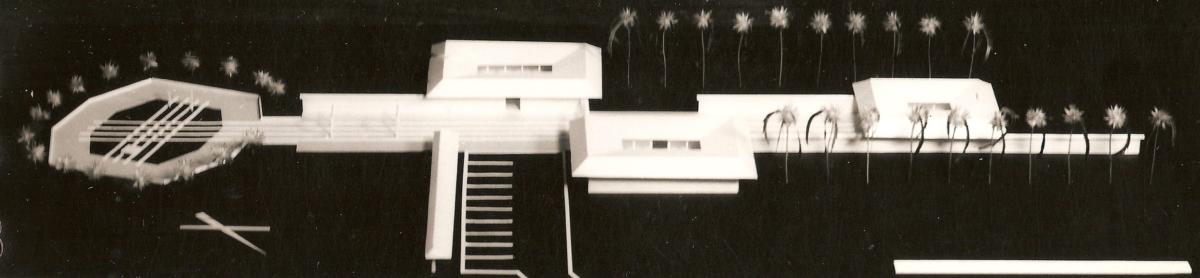

This book reconceptualized these deployments of architectural labor as part of urbanization processes. Its protagonists participated in the production of all functional programs, from housing to infrastructure, and on all scales, from buildings to landscapes. They assisted local professionals in setting up construction-materials industries, in modernizing traditional building technologies, and in implementing mechanized construction procedures. They contributed to the formulation and promulgation of professional guidelines, building codes, architectural standards, urban norms, and territorial regulations, including principles of land use, transportation, land tenure, and governance. Their drawings and models, even when left unrealized, provided impulses to envisage new urban futures in the territories where they worked. They contributed to the formation of professional, research, and educational institutions in architecture and planning, thus preparing the ground for local production of knowledge and pedagogy. By thinking Accra through Tashkent and Baghdad through Warsaw, they diversified the conceptual references of urbanization, while specialized research institutes in Weimar, Szczecin, Gdańsk, Prague, Budapest, and Moscow began to provincialize Western imperial capitals as centers of knowledge production about urbanization. While neither the only nor the most dominant actors in these processes, architects contributed to them in ways that often transgressed their initial remits and redefined the consensual understanding of what architects do as architects.

Eastern European architectural labor in West Africa and the Middle East was both postcolonial and socialist. It was postcolonial in the sense that independence fundamentally changed the conditions of architectural production in Ghana, Nigeria, Iraq, and the Gulf, the continuities with the preceding period notwithstanding. This meant the establishment of new and reorganization of old institutions, but also the emergence of new clients, new programs, new discourses, and new ambitions that defined the parameters and stakes of architectural production. For many, the arrival of Eastern Europeans promised to break the vicious circle of underdevelopment in which the damage inflicted by the colonizers on the colonized could be undone only with the resources and knowledge of the former colonial center. While these dynamics have rarely been done away with, the arrival of these architects complicated them, not the least by disrupting the division of spaces and times assigned to non-Europeans and Europeans in a design institute, an administrative office, or an architectural school. In the wake of independence, their engagements were considered a temporary measure and conceived as a bridge between colonial dominance and the period when the local cadres would take over, even if the latter often turned out to be postponed for decades.

Eastern European officials wanted to see these working relationships as specifically socialist and fundamentally different from Western attempts at exploitation of the former colonies. Such claims were used in diplomatic offensives of the socialist countries in Africa and Asia and by foreign trade organizations to discipline the professionals they sent on export contracts. At times, Eastern European architects and planners themselves referred to the discourse about socialist labor. For a few among them, this discourse helped to make sense of their deployment abroad, while others used it to secure new commissions or to claim more resources from the authorities back home. When interviewed today, some architects contrast the professionalism of the traveling personnel from Eastern Europe with the negative selection of their Western counterparts (“Failed in London, try Hong Kong,” as a British saying went). Such statements might convey their frustration with the unequal treatment they sometimes experienced from local commissioners in comparison to Western professionals, combined with pressures from state-socialist institutions. Most, however, saw themselves on par with their Western peers, either as members of the international architectural culture or, later, as part of the worldwide mobile workforce: liquid, contingent, and “free” to be deployed everywhere. These various and evolving readings notwithstanding, the export of architectural labor from socialist countries was consistently conditioned by the political economy of state socialism, from the organization of architecture and construction in Eastern Europe, to the state monopoly on foreign trade.

The controversies around socialist labor point to what might be the main dilemma of this book: the relationship between the studied architectures and the project of socialism. This relationship was addressed by means of the concept of socialist worldmaking, or visions of global cooperation practiced by actors from socialist countries against the delineations of the world inherited from the colonial period and in competition with other projects of global cooperation after World War II. Socialist worldmaking included, but was not limited to, the claim to the worldwide applicability of the socialist path of development; the worlding of Eastern Europe, or the sharing with the developing countries of the Eastern European experience of overcoming underdevelopment, colonialism, and peripheriality; and collaboration within the world socialist system. So understood, socialist worldmaking informed the changing geographies, volumes, speed, distribution, and programs of architectural resources that were moved between Eastern Europe and the Global South.

In several of these locations, architectural resources were deployed in programs of socialist modernization. This was the case in Ghana under Nkrumah, where architecture and the construction-materials industry were reorganized with an aim to become integrated into a centrally planned apparatus put in charge of state-led industrialization, collectivization of agriculture, and an egalitarian welfare provision. This architectural production contributed to the undermining of inherited spatiotemporal divisions of the Ghanaian society and their redistribution according to the new socioeconomic order envisaged by the Convention People’s Party. In the Ghanaian mass media, this architecture was often acknowledged as a signifier of what a socialist everyday meant, thus staking out a field of debate that was relevant and meaningful for actors operating on the ground, who sometimes remember its empowering effects.

However, the review of the Soviet engagements in Ghana showed the limits to the country’s socialist modernization, in particular in terms of implementing the principles of central planning. Similarly, the emancipatory targets of the worlding of Eastern Europe were challenged both by the increasingly mercantile motivations of the socialist countries in their exchanges with the Global South, and the ambiguities of Eastern Europe’s own colonial past. In turn, some of the core ideas of the world socialist system, including that of the socialist international division of labor, were directly undermined by the competition in the Global South between Comecon countries themselves. By the end of the Cold War, the export of socialism was rarely within the remit of architects, planners, and contractors from Eastern Europe, as exemplified by Energoprojekt’s instruction not to involve foreign workers on export contracts in self-management procedures.

Some readers may draw conclusions in the manner in which Western Marxists assessed the urbanization in state-socialist Europe: as a failure to fulfill the socialist promise of a new type of space. However, such whole-sale critique of the engagements discussed in this book would obscure their specificity and their emancipatory potential. What the preceding chapters showed was that the mobilities of architecture from Eastern Europe made a difference in West Africa and the Middle East: both in the sense of having a huge impact on people’s everyday lives, and in a more literal sense, of differentiating urbanization processes beyond the consequences of the colonial encounter with Western Europe and the hegemony of global capitalism.

This book can be read as a history of such differentiated urbanization in Accra, Lagos, Baghdad, Abu Dhabi, and Kuwait City. In the preceding chapters, differences were understood not as essentialized particularities of a specific place that lend themselves as candidates for cooptation into the colonial (or neocolonial) system of governance, or as opportunities for capitalist value-extraction and commodification. But neither were they theorized as resulting from grafting an original Eastern European technology or a design concept in Africa or Asia, nor from adapting such technologies and concepts to the ontological irreducibility of these territories. Rather, difference was understood as divergence, contrast, disparity, and sometimes incommensurability or contradiction between the economic, financial, ideological, logistical, regulatory, and cultural regimes within and across which Eastern Europeans, West Africans, and Middle Easterners worked.

By aiming to make the most of such relational differences, the protagonists of this book practiced worldmaking — for example, by negotiating the entrance protocols and gatekeeping procedures of competing networks of architectural resources. Among such differences, I paid particular attention to those between the political economy of foreign trade in Comecon countries and the emerging global market of design and construction services dominated by Western enterprises. Working across both systems provided incentives for the use of barter agreements, which resulted in the Romanian practice of redrawing plans so that they could be constructed by means of materials, technologies, and labor from Romania bartered for crude oil. In turn, Polservice exploited the inconvertibility of the Polish currency in a way that shaped the working conditions of Miastoprojekt’s team in Baghdad. These conditions differed from those of previous foreign planners in Iraq, both in terms of the size of the team, its composition, and time spent in Baghdad, and in terms of their relationship to the Iraqi authorities and collaborators. These working conditions provided the Polish and Iraqi planners with resources to produce a master plan that was embedded, empirical, interdisciplinary, consultative, and scenario-based.

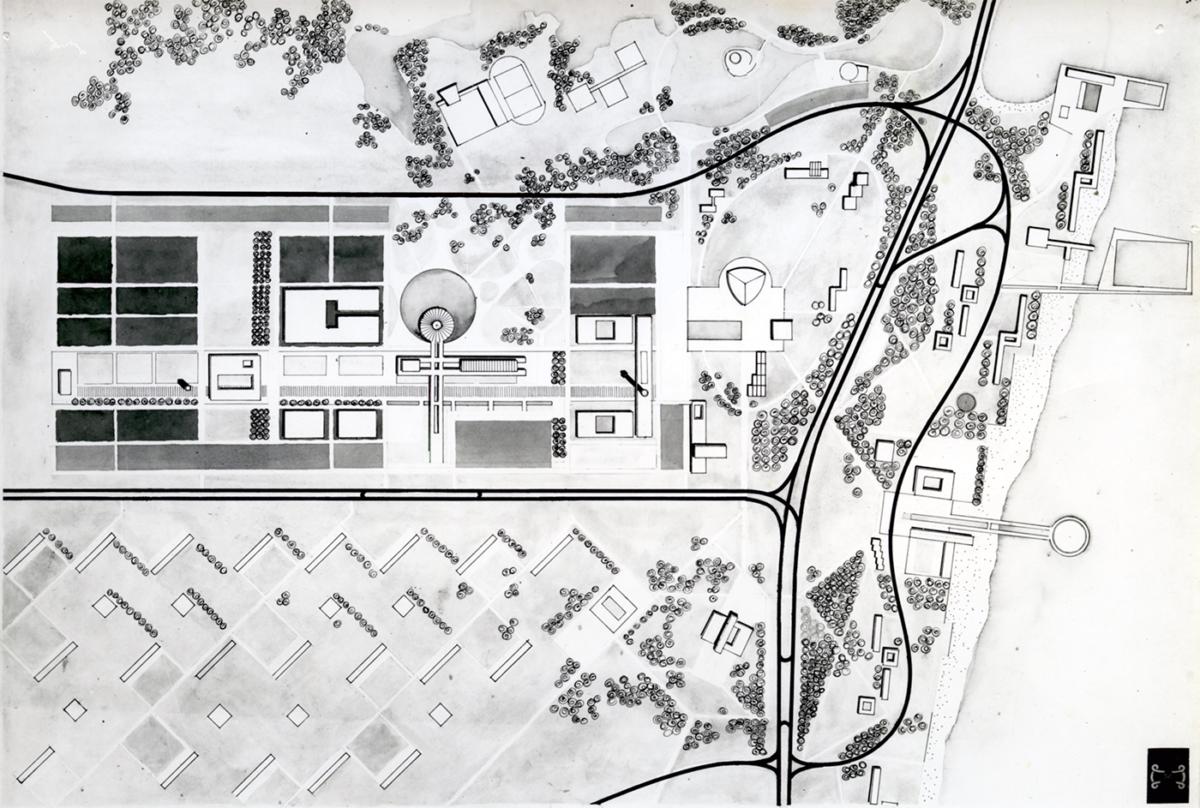

Few in Baghdad attributed this character of the master plan to socialism, and even fewer would so describe its consequences, including the ways in which the plan was negotiated, implemented, modified, and, ultimately, how it guided the urban development of Baghdad. In other locations revisited in the preceding chapters, too, differences that resulted from socialist worldmaking continue to be reproduced beyond their original association with socialism, and often in unexpected ways. Sometimes they result in accelerated development — for example, when a factory built by Eastern Europeans in Ghana brought about training opportunities into remote locations and expanded the skills of the local people they could draw upon long after the factory was closed in the wake of Nkrumah’s fall. At other times, they result in slowdowns and obstacles to rapid urbanization — for example, at the International Trade Fair in Accra, where Nkrumah’s nationalization policies led to still unresolved conflicts around land ownership. Elsewhere, they lay out distinct vectors of urbanization, as has been the case with the infrastructural grid of the International Trade Fair in Lagos. In turn, the wide area around the National Theater continues to inspire new ways for imagining the future of Lagos, its transportation networks, and its everyday economies. The concept of socialist worldmaking provided a way to account for the genealogy of these differences, but the understanding of their reproduction requires new methods, new hypotheses, and new concepts: as much a theoretical as a political task.

Excerpted from ARCHITECTURE IN GLOBAL SOCIALISM: Eastern Europe, West Africa, and the Middle East in the Cold War by Łukasz Stanek. Copyright © 2020 by Łukasz Stanek. Published by Princeton University Press. Reprinted by permission.

Imprint

| Author | Łukasz Stanek |

| Title | Architecture in Global Socialism |

| Publisher | Princeton University Press |

| Published | 2020 |

| Index | Łukasz Stanek Princeton University Press |