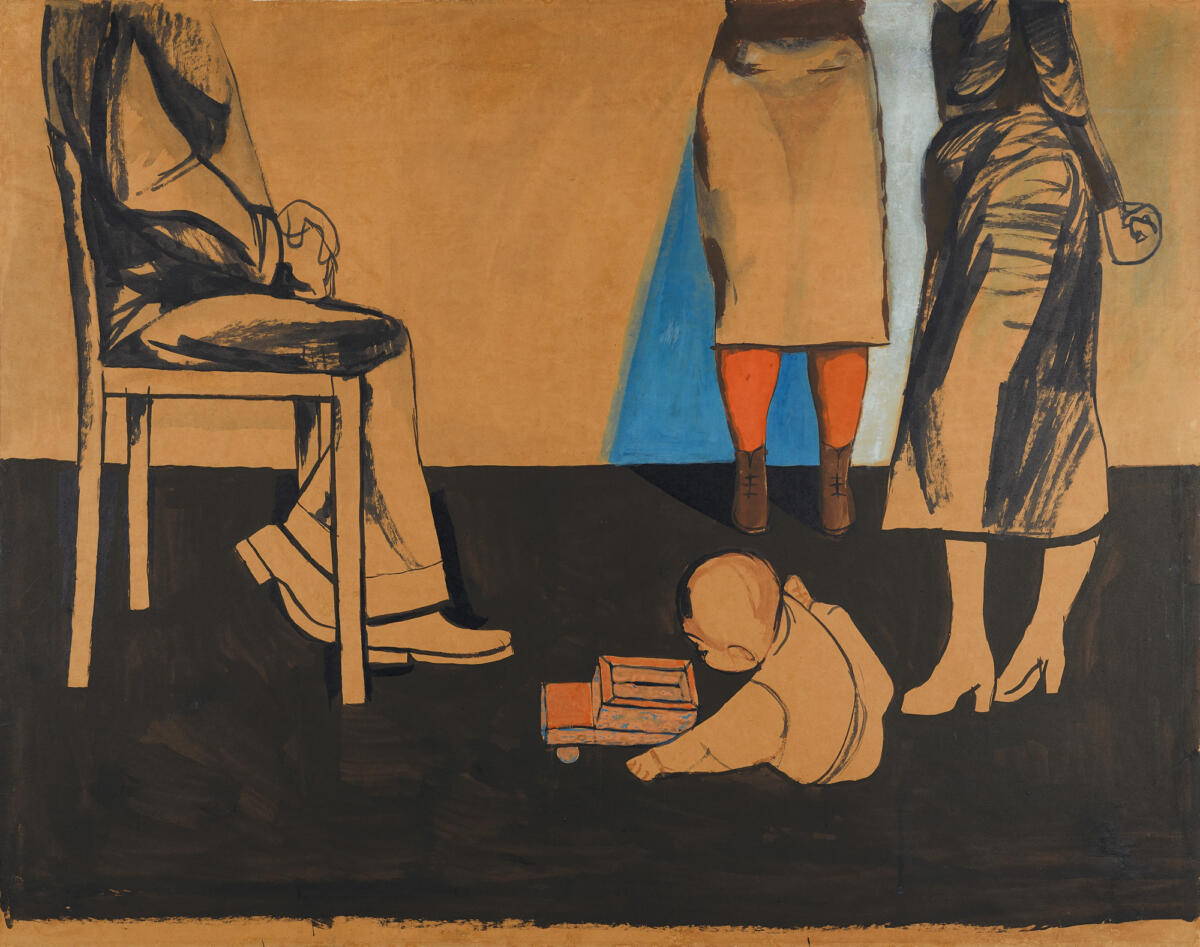

Andrzej Wróblewski “submitted a poor painting”—wrote Elżbieta Grabska, historian and art critic, recalling Wróblewski’s participation in the Polish Exhibition of Young Art under the slogan “Against War, Against Fascism” held at the Warsaw Arsenał in the summer of 1955.[1] Although several reviews mentioned his painting Mothers, Anti-Fascists, little was written or said about Wróblewski himself. “No one complained, no one demanded an award,” wrote Janusz Bogucki some years later. There were almost forty distinctions awarded at the exhibition. “Perhaps his painting was too restrained to be appreciated among the raging sensibilities of artworks setting the tone of the Arsenał exhibition.”[2] Wróblewski’s canvas—with its classical composition reminiscent of the iconography of St. Anna, the mother of Mary and the grandmother of Jesus, and domestic themes—definitely stood out alongside Isaac Celnikier’s moving Ghetto, Marek Oberländer’s Stigmatised [Napiętnowani] or Waldemar Cwenarski’s The Blaze [Pożoga], paintings whose titles and themes evoked the memories of war. His was definitely an uncompromising representation of his own experiences and the particular role he had assigned to shapes and colors that conveyed man’s socio-moral condition. In an essay exploring the latest artistic developments, including the activities of artists associated with the Arsenał exhibition, Marcin Czerwiński saw in Mothers, Anti-Fascists “the path of emotional drama, stemming from the color tissue of the image,” which Wróblewski and several other artists represented. “Thus, this direction [in painting]—strongly exacerbating such image-forming factors as weight, color dissonance within the ‘painterly matter’ itself—achieved the emotional coloring contained within the space between detestable dread and affirmative power, fitting the narrative of the image (e.g., in Wróblewski’s Motherhood, where affirmation and trust are expressed via the immense material presence of the mother’s figure).”[3]

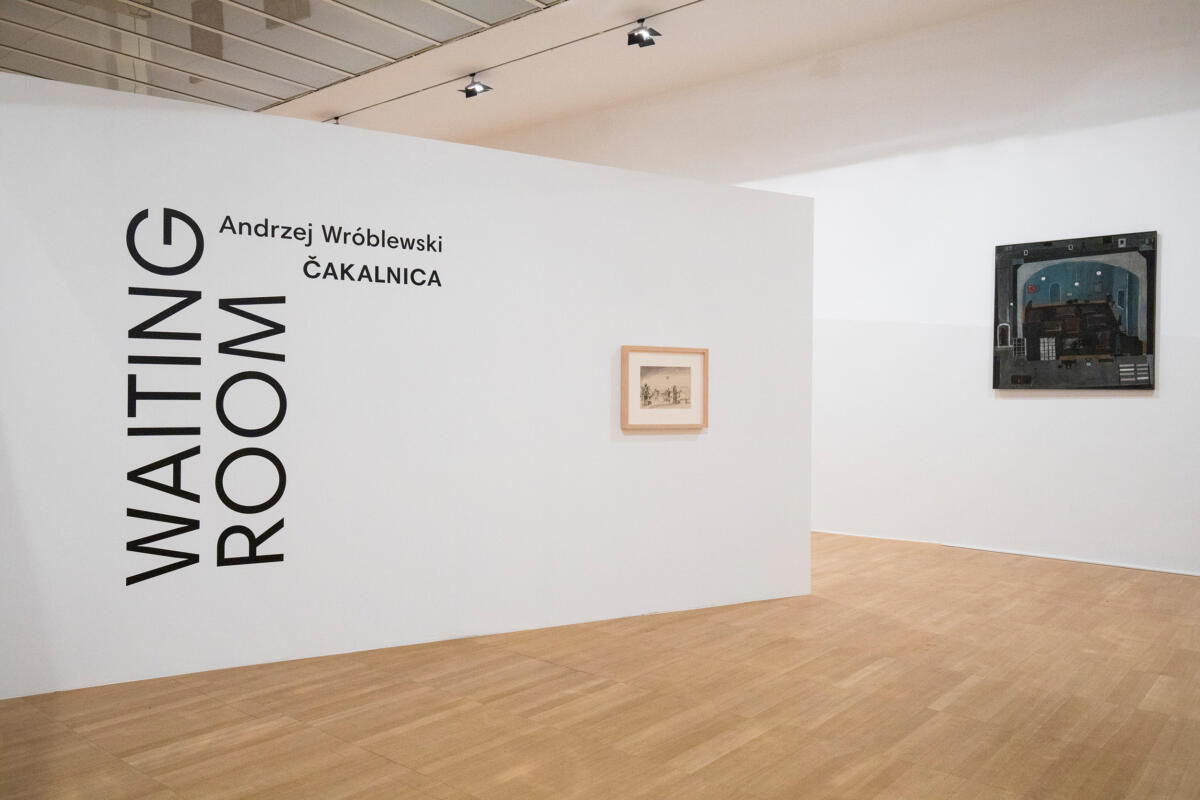

Why do we return to Mothers, Anti-Fascists today, and why does this painting play such a significant part in the exhibition Andrzej Wróblewski. Waiting Room and the accompanying publication? Firstly, because it was the first painting submitted to a nationwide exhibition, in which the artist abandons the language of Socialist Realism. “The organizers of the exhibition … they wanted to create radical, socially engaged art, but also art liberated from the burden of intrusive didactics and the expression of academic realism and post-imperialism’s formal prescriptions that cripple authenticity.” Because of that, according to Bogucki, Wróblewski “was probably the only Polish painter who, in a manner far removed from common literalness, coyness, or exhibitionism, was able to bear witness to the truth of those difficult years, at the time slowly sliding into the past.”[4] Secondly, Wróblewski had so far only portrayed the themes of a nursing mother and everyday motherhood in the intimate form of small ink studies. Thirdly, in Mothers, Anti-Fascists—importantly, the artist added the second part of the title on the eve of submitting the painting to the exhibition, June 3, 1955—Wróblewski introduces figures, to whom he will devote the following months of work—people waiting or pinned to chairs. The eponymous waiting room is much more than just a symptomatic metaphor of the social conditions of the Thaw period. It exposes the inertia of materiality of surroundings and the sterility of mental economy. We understand the waiting room as daybreak—the moment right before the dawn, the harbinger of upcoming changes or transformations. The waiting room—the stage of chairings and expectations—foreshadows that which is yet to come.

The exhibition Andrzej Wróblewski. Waiting Room and its accompanying publication unfold in six parts. The eponymous Delegates of the first section are, of course, Andrzej Wróblewski and Barbara Majewska. In the opening essay entitled Everything That Passed Will Play Out Anew… Magdalena Ziółkowska outlines the artistic, political, and social dimensions, in which—following years of postwar scarcity and Stalinist terror, a period of creative apathy and indifference—the Chairings and Queues of the Thaw period were created. Ziółkowska points to the parallel nature of historical events culminating in Władysław Gomułka’s rise to power and the artist’s work during that period, which was the sum total of the baggage of life experiences and personal challenges that Wróblewski carried with him on the eve of his delegation to the countries of the former Yugoslavia. The essay examines Wróblewski’s identity as an art critic and painter in the early autumn of 1956, and the circumstances surrounding his appointment as the official representative of the political transformations of the Polish October. In Andrzej Wróblewski’s Visit to Yugoslavia and Cultural and Political Preconditions for a Renewed Cultural Exchange Between Yugoslavia and Poland in the Mid–1950s, Ljiljana Kolešnik describes the conditions of cultural exchange between Poland and Yugoslavia and the artistic landscape that Wróblewski and Majewska encountered there. However, it is the reconstruction of the trip to Yugoslavia, which Wróblewski and Majewska took together between October 30 and November 21, 1956 that constitutes the axis of the historical narrative around which the threads of political and artistic relations between the two countries during the thaw interweave. The collected archival material, photographs, documents, and works of art indicate that Wróblewski was directly inspired by Yugoslav contemporary art, the work of Lazar Vujaklija and Ivan Mestrović, but also the country’s landscape, folklore, local architecture, and stećci—carved stone tombstones.

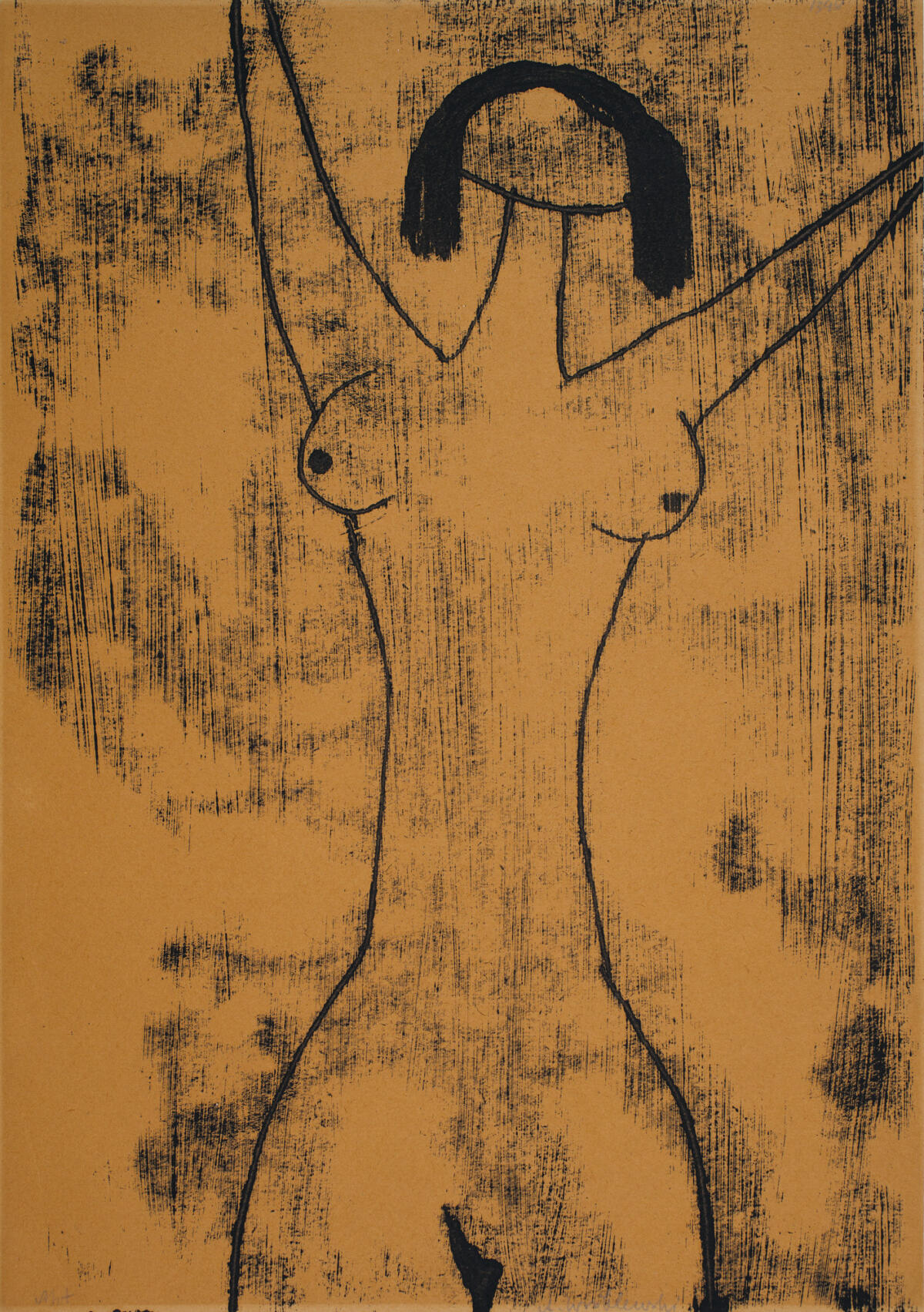

Works created by Wróblewski following his return from Yugoslavia and in the last four months of his life are stamped with a striking atmosphere of anticipation—or, perhaps, a terrifying sense of demise. Some of them focus on the petrification or objectification of the human body—skulls, dismembered, decapitated, and maimed bodies, others on themes for tombstones and funerals. Their complete form is the monumental canvas Tombstone, (Tombstone of a Womanizer), whose protagonist, the Womanizer, is full of contradictions. Dead, and yet he is smiling, constantly wearing a scornful expression. His tombstone is adorned with votive offerings: the slender legs of a woman. Their erotic shape adds piquancy to the typical silhouette of the Bogomil stećak. The moment when a new vision opens up to overcome what had seemed an irreversible choice between historical suffering and the end of history, is described by Ivana Bago—author of Dialectics at a Standstill: Andrzej Wróblewski as a Yugoslav Heretic—as the eponymous dialectic of impasse. She relates this to the presence of South Slavic folk culture, precisely in the form of funerary sculpture attributed to the Bosnian Christian heretical sect, the Bogomils, that could be read as an uncanny, if not ironic, synchronicity, in relation to Wróblewski’s post–Slavic works. The figure of the Womanizer thus constitutes a roadmap to the artist’s iconographic will, i.e., a collection of eighty-six monotypes, probably created at the turn of 1956–57. It is in this technique that Wróblewski evokes themes present in his early work—fish, horses, violins, vehicles, and the chauffeur; but one subject firmly occupying the artist’s attention is the female body transformed in countless ways and depicted with numerous attributes. The woman—stretched out on a cross, transformed into a rose, objectified into a chair, covered with a veil, or wearing lingerie—is the bearer of sexual power.

The figure leading us through the waiting rooms of frozen silhouettes and frozen faces in the third chapter is the Chaired Man. He is more a specter than a hero/protagonist, waiting hopelessly, tormented by the constraints and pathologies of the social system, and so are the heroes of this section—as if they froze for a moment, concentrating, waiting for something to happen, standing next to each other in a world suspended in time, on the brink of an undefined future. They do not talk to each other; they don’t look at each other. Even when Wróblewski portrays a young model—Ola Peterschein—the canvas is permeated with an atmosphere of deaf timelessness, in which he achieves absolute mastery. In the essay East to West: When the Wait is Over, Marko Jenko analyzes the topos of waiting, or the “visual articulation” of what is happening in the waiting room, the scene recalled by Heiner Müller. In it, Jenko asks: “the waiting room—how come? Is it because socialism was, from the outset, so marked by waiting in all aspects of everyday life?[5] Why are people turning into chairs and why is this phantasmagorical event very much a real one, and in painting a realist one?”

Mothers and daughters, nurturers, carers, lovers, and wives possessing a life-giving strength, parental might, and sexual power, are the protagonists of the fourth section, devoted to home life and the everyday events of motherhood. The intimacy of Wróblewski’s portraits of his wife, female nudes, scenes from the interior of his Kraków apartment and the studio of this declared “anti–bourgeois” and non–conformist, sketched daintily in ink, provide a counterbalance to the Mothers, Anti-Fascists and Laundry canvases prepared with the exhibitions at Arsenal and the “Po Prostu” Salon in mind. In her essay Nursing and Reading. Affective Realism in Andrzej Wróblewski’s Painting, Ewa Majewska reinstates privacy to such scenes and interprets them as an element of the socio-political sphere.

A separate section of both the exhibition and publication is dedicated to the figure of the Boy—a teenager, standing against the yellow wall of the artist’s studio. He is now alone, although he once stood among a group of captives and families about to be executed; among the now human-less coats and jackets. He appears at a bus stop, against a wall, next to a statue of Gudea. In We L:ook at These Paintings in Silence … Wojciech Grzybała explains that this is one theme of Wróblewski’s work that has not been widely recognized so far.

In the final section, the Protagonist emerges—a hero with a twofold nature, heading for the unknown, beyond the horizon, somewhere straight ahead, in a timeless vehicle. Sometimes, he is the chauffeur, other times —the passenger. As Branislav Dimitrijević writes in his essay, Wróblewski’s Rückenfigur, this double figure is also the literary protagonist of Różewicz, Apollinaire, and Lorca’s poetry—visually untranslatable, but filled with a suggestive mood.

The text was first publish in Andrzej Wróblewski. Waiting Room, eds. Magdalena Ziółkowska, Wojciech Grzybała (Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, Warsaw: Andrzej Wróblewski Foundation), pp. 29-32.

[1] Elżbieta Grabska, “Sztuka była na pierwszym miejscu. Rozmawiał Waldemar Baraniewski” in Powinność i bunt. Akademia Sztuk Pięknych w Warszawie 1944–2004 (Warsaw: Academy of Fine Arts, Zachęta – National Gallery of Art, 2004), p. 111.

[2] Janusz Bogucki, Sztuka Polski Ludowej (Warsaw: Wydawnictwa Artystyczne i Filmowe, 1983), p. 104.

[3] Marcin Czerwiński, “Uwagi o młodych,” Przegląd Artystyczny, no. 3–4 (1955), p. 35.

[4] Bogucki, Sztuka Polski Ludowej, p. 134.

[5] See Sheila Fitzpatrick, Everyday Stalinism: Ordinary Life in Extraordinary Times, Soviet Russia in the 1930s (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999).

Imprint

| Artist | Andrzej Wróblewski |

| Exhibition | Waiting Room |

| Place / venue | Moderna galerija, Ljubljana, Slovenia |

| Dates | 15 October 2020 – 10 January 2021 |

| Curated by | Wojciech Grzybała, Marko Jenko, Magdalena Ziółkowska |

| Website | www.mg-lj.si |

| Index | Andrzej Wróblewski Magdalena Ziółkowska Marko Jenko Moderna Galerija in Ljubljana Wojciech Grzybała |