Memory is like an always-departing body with its own history and timeframe, its own delimiters and politics, deeply sensual, personal, like a moving vehicle propelled by paper documents, images, ephemera, realia, and other physical and nonphysical remains.

The notion of “cultural memory”—that is, a culture (i.e., a people) presided over by a governing body (i.e., the state), which maintains jurisdiction over written accounts, activities that are helpful for storing and retrieving information (i.e., memory)—is either going through a renewal or extinction in contemporary art, depending on who you ask.

In Slovenia, a small central European country known just as much for its mountains and ski-resorts, as well as being the home of Slavoj Zizek, the idea of attending a show about memory and migration seemed a curious choice.

Concomitant with the rise of cultural memory, the so-called “end of history” has been predicted for decades, if not centuries—from Hegel to the French philosopher and mathematician Antoine Augustin Cournot. As early as 1861, Cournot referred “to the end of the historical dynamic with the perfection of civil society.” While more recent accounts by those such as Francis Fukuyama, the acclaimed American political philosopher, prophesied the “end of history” — a belief that, after the fall of communism, free-market liberal democracy had won out and would become the world’s “final form of human government.”

However such predictions have been challenged in recent years with the rise of ethno-nationalism and a far-right resurgences, particularly in Europe, where the European Union has been forced to come to terms with an emergent, populist, illiberal wave, challenging Europe’s long-standing socialist democratic traditions.

In Slovenia, a small central European country known just as much for its mountains and ski-resorts, as well as being the home of Slavoj Zizek, the idea of attending a show about memory and migration seemed a curious choice. For one, Slovenia remains a welcoming place for refugees. Although the population is not homogeneous, the majority is Slovene, the country has fared relatively well with integrating refugees, while many of its neighbours like Hungary and Austria, face the emergence of a growing wave of identitarian politics, fearful, it not outright antagonistic to refugees.

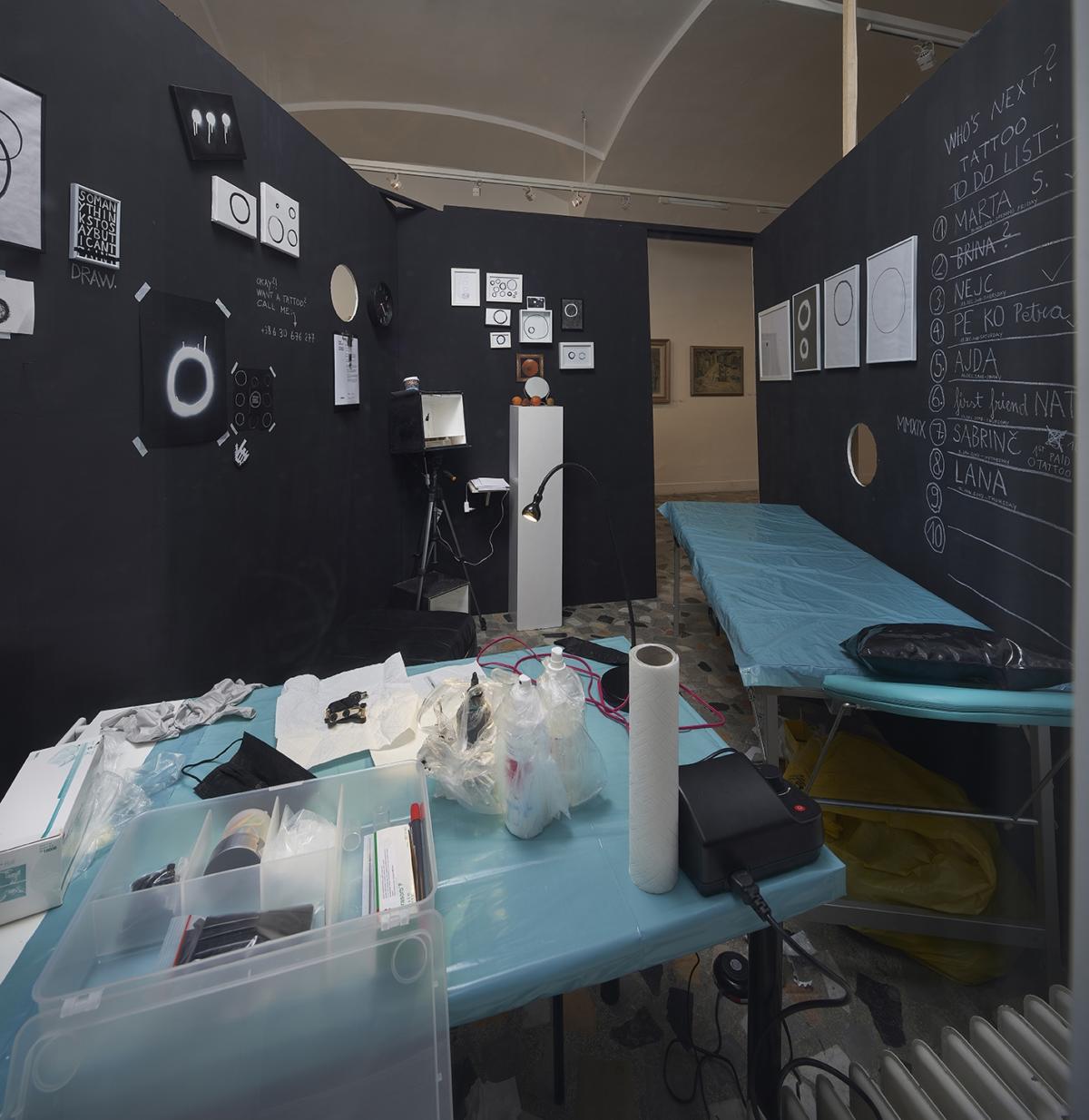

It is against this backdrop that the exhibition “No Looking Back, Okay?”, at the UGM Maribor Art Gallery, aims to tackle the manifold ways in which the past is increasingly politicized today. Curated by Simona Vidmar (together with curatorial assistant Jure Kirbiš), the exhibition includes 18 artists and duos, organized according to definitions of memory with many numerous adjacent themes to today.

In Adel Abdessemed The Sea (2008), for instance, a single channel projection video projection documents the artist’s absurd efforts to spell out the phrase “politically correct.” While balancing on a wooden dingy at sea, the inanity of this gesture lies in the fact that it is an almost impossible task. With waves crashing around him, the 10 second loop touches on the brutally enforced, and often failed immigration policies that, in the last several years, have begun to take shape in Europe. Touching on themes like exile and displacement, Abdessemed’s work references the idea of memory as an identitarian project, one that is often used by right-wing groups in Europe who promote fear of the Other as a means of stirring ethnic-nationalism.

While in Homesick (2014) by Hrair Sarkissian, the lived memory of architecture and its power to construct a sense of belonging is given scale. In a two-channel video projection, the artist recreates and subsequently destroys an architecturally exact model of the apartment building in Damascus where his parents live.

As a counterpoint to some of the more serious and politically charged works in the exhibition, humour is also another feature. Case in point being Francis Alÿs’s Lada Kopeika Project, St. Petersburg (2014), which documents being behind the wheel of a Lada, the famous brand of car produced during the Soviet Union, while speeding through the courtyard of the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg, eventually crashing into a tree.

As a symbol, the car references progress and modernity, but in Saudi Arabia — where until last year women were barred from driving — the car also symbolizes a markedly contested space. In Sarah Abu Abdallah Saudi Automobile (2012), for instance, the artist imagines a new interior for a depilated car. However, rather than fixing it and restoring its original functionality, the artist instead envisages it almost as a domestic, inhabitable space.

In Allora & Calzadilla’s How to Appear Invisible (2009), memory is treated with reference to well-known political symbols of the former GDR. The video takes place around the former GDR headquarters in Berlin, albeit shown from the perspective of German Shepard dog walking around the ruins wearing a collar fashioned from an American fast-food container. As the camera follows the dog trekking happily through the rubble, the political symbols of the former Soviet empire are laid bare, in sweeping, iconoclastic shots, the video seems to comment on the idea of memory as a contested space.

Al Solh’s work reminded me of Tolstoy’s famous maxim that he wanted to write fiction because he thought it would allow him to get closer to the truth. Today, in an era arguably marked by post-truth dichotomies confusing fact and fiction, a nonlinear aesthetic has seemingly emerged.

In art and politics, iconoclasm is a frequent subject of debate. Iconoclasm, if taken at face value, harbours an incisiveness towards objects and their symbolic value, which are then destroyed or altered to suit the ideology of an incoming party (or, in some cases, a single fascist leader). In contemporary art, as in politics and history, the act of discombobulating an idol, physically speaking, by destroying it, rejects the values or established beliefs that the object or image is thought to embody.

Historical fiction and satire is also a theme in the exhibition. In Mounira Al Solh’s large-scale paintings, by far my favourite work in the exhibition entitled Reclining Man with Sculpture 1−5 (2008−2017), the artist combines real political figures from the Middle East and places them in ludicrous, oftentimes humous situations. The large-scale paintings employ healthy doses of irony and camp, poking fun at political leaders depicted in moments of excess, surrounded by the trappings of plunder and wealth.

Al Solh’s work reminded me of Tolstoy’s famous maxim that he wanted to write fiction because he thought it would allow him to get closer to the truth. Today, in an era arguably marked by post-truth dichotomies confusing fact and fiction, a nonlinear aesthetic has seemingly emerged.

Here, with distinctions between fact and fiction blurred, the limits of memory—and with it the expansive concept of history—underscored by the exhibition’s title: “No Looking Back, Okay?”, asks us to look forward, rather than back, formulating a new prospectus of history and memory, but not in the Fukuyamaian sense (i.e. ‘an end of history’), but rather as a kind of counter-position to the seemingly endless feedback loop of history and memory as a narrated aphorism on stage with the dwindling concept of the nation state.

The exhibition, as such, attempts to construct a nonlinear trajectory of history and memory, a post truth form perfectly calibrated to a post truth era. Indeed, it is, like Mark Fisher writes in Capitalist Realism, “what is left when beliefs have collapsed at the level of ritual or symbolic elaboration, and all that is left is the consumer-spectator, trudging through the ruins and the relics.”

Imprint

| Artist | Adel Abdessemed, Sarah Abu Abdallah, Allora & Calzadilla, Mounira Al Solh, Francis Alÿs, Nika Autor, Morten Barker, Nataša Berk, Ana Dana Beroš, Jasmina Cibic, Cao Fei, Vadim Fishkin, Tanja Lažetić, Nina Mangalanayagam, Emeka Ogboh, Agnieszka Polska & Witek Orski, Hrair Sarkissian, Massinissa Selmani |

| Exhibition | No Looking Back, Okay? |

| Place / venue | UGM Maribor Art Gallery |

| Dates | 30 November 2018 – 17 March 2019 |

| Curated by | Simona Vidmar |

| Website | www.ugm.si/en/ |

| Index | Adel Abdessemed Agnieszka Polska & Witek Orski Allora & Calzadilla Ana Dana Beroš Cao Fei Dorian Batycka Emeka Ogboh Francis Alÿs Hrair Sarkissian Jasmina Cibic Massinissa Selmani Morten Barker Mounira Al Solh Nataša Berk Nika Autor Nina Mangalanayagam Sarah Abu Abdallah Simona Vidmar Tanja Lažetić UGM Maribor Art Gallery Vadim Fishkin |