The worldwide literature describing research into and commenting upon creative works referring in various ways to the trauma and memory of the Second World War grows in volume with every passing year and probably surpasses the number of such artworks even though that number increases annually as well. Successive generations of artists highlight ever new aspects of the subject and use diverse forms to refresh and sharpen our collective memory, dulled by the intervening decades. Likewise, successive generations of researchers revisit well-known works of art to reveal aspects of them previously missed. One of these aspects is a factor shared by a sizeable group of artists, relating to the fact that the unique phase of life that is adolescence coincided for them with the war.

Without going into psychological, psychiatric, and purely medical considerations on this period in a person’s life, we can say on a general level that it is in itself perceived as something traumatic, and under certain circumstances, occasioned by family life, relations with the peer group, the education system, or the circumstances surrounding sexual initiation, this time can have a decisive impact on the rest of that person’s life. If we add such factors to this handful of variables as the death of one of the parents and confrontation with the day-to-day realities of war, its demoralization and obscenity, we receive a very unique ‘wartime adolescence syndrome’, which entails an equally unique stigma.

The focus of my interest is the ‘war-infected’ work of three representatives of that generation: the sculptress Alina Szapocznikow (1926-1973), the director Andrzej Wajda (1926-2016), and the painter Andrzej Wróblewski (1927-1957). They share not only close birth dates but also similar experiences of adolescence in terms of time and place: the war in Poland began on 1 September 1939 and lasted almost six years, during which every town and village in Poland was the scene of unprecedented crimes inflicted on its populace. What they witnessed and partook of marked in a very singular way both their lives and their work, whose full interpretation was impossible as long as the Polish collective memory was restricted by the political directives handed down from Moscow.

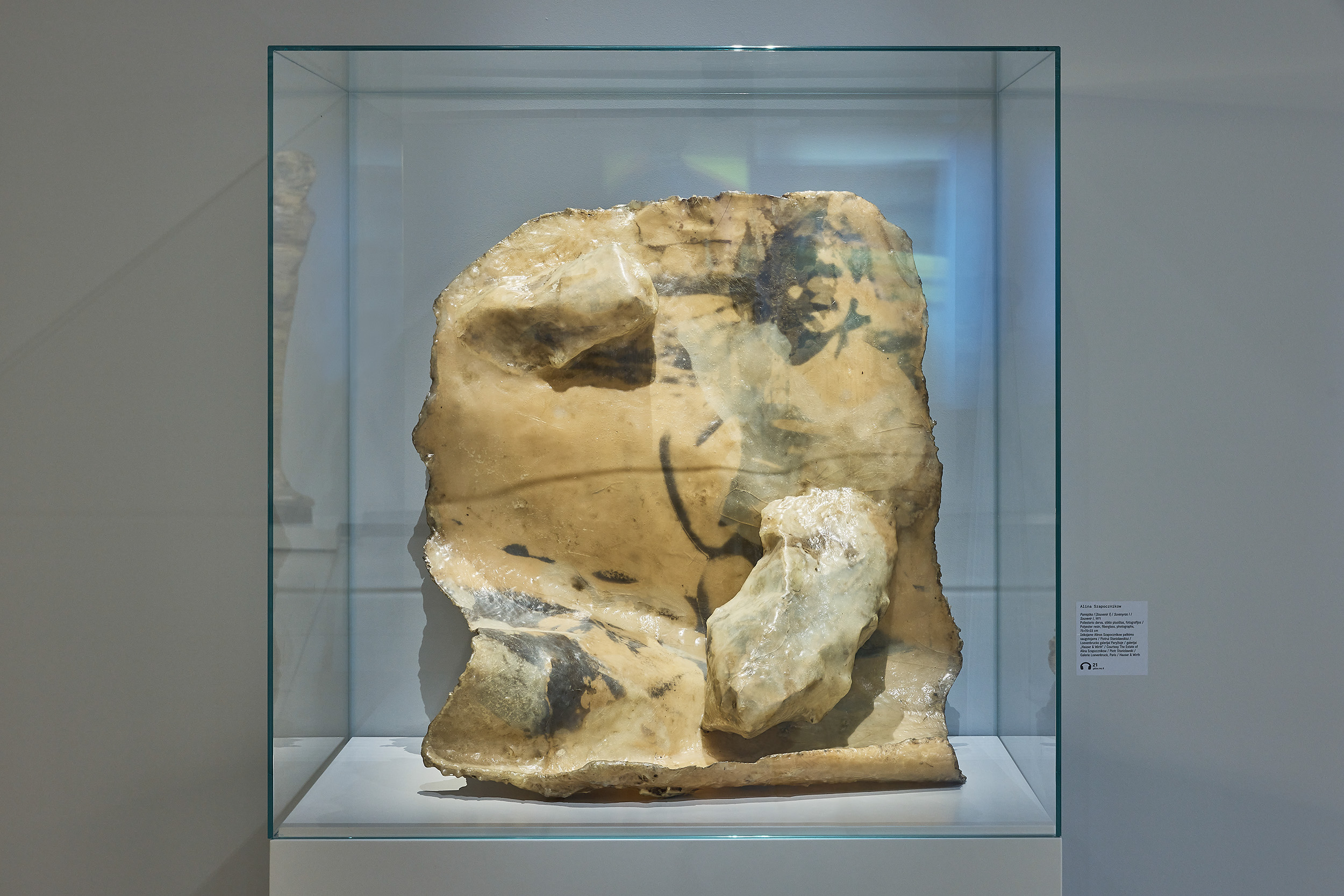

‘A Difficult Age. Szapocznikow – Wajda – Wróblewski’, exhibition view at Mo Museum, photo courtesy of MO Museum / Norbert Tukaj

In 1962 Jerzy Grotowski and Józef Szajna transferred the action of Stanisław Wyspiański’s play Acropolis from the cathedral on Wawel Hill in Kraków to an extermination camp. ‘Hence’, Dorota Sajewska writes, ‘Acropolis becomes a philosophy of theatre recorded in the drama of reconstruction, based on examining the boundary between life and death, organic and non-organic matter, man and object, and, finally, between an event and the process of its documentation.’[1] In this production, the obscenity of war became one with a scene of the perennial ritualistic cult of death, a necro-performance, which was continued by Szajna in his subsequent productions and three-dimensional paintings exhibited in art galleries. Different in form, but similar in essence, necro-performance was also practised by Tadeusz Kantor in his happenings (e.g. An Anatomy Lesson after Rembrandt), and in all his theatrical productions, from The Dead Class in 1975 to Today is my Birthday, staged soon before his death in 1990 and publicly performed just after his passing away. Kantor is constantly present on stage in them, as the mover and conductor of the performance acted out by dead characters ‘summoned back from non-existence’. This ad personam presence is intended to separate clearly the living from the dead, real existence from theatrical fiction. But he himself, as a figure ‘inscribed’ into the suspension of disbelief germane to the stage, is also an actor playing the role of Tadeusz Kantor.

Such a structure, that of a narrative of the artist’s own existence embedded in a work of art, was also used by Andrzej Wajda in the prologue to Pilate and Others, where he interviews a ram that is leading a flock of sheep to the slaughter. What seems more relevant in his work, however, is his references to cultural/tribal substitutive gestures, such as a corpse-mannequin being run over by a car in Everything for Sale, or an effigy representing a wartime ‘German’ being tossed into a fire in Landscape after Battle. This ceremonial reversing of the roles of perpetrator and victim was an overture to the staging of the Battle of Grunwald by liberated and re-interned prisoners of concentration camps.

In his ‘Notes on Gestures’, invoking and referencing other researchers, Giorgio Agamben formulates the thesis that all images can be interpreted as freeze-framed gestures.[2] He writes: ‘Even the Mona Lisa, even Las Meninas could be seen not as immovable and eternal forms, but as fragments of a gesture or as stills of a lost film wherein only they would regain their true meaning.’ The concept used on this occasion, that of a gesture as a sign of being lost in language, leads us to attempt to read the theatrical and film productions referred to above as gestures threaded onto a conventional narrative weft and signifying the powerlessness of worn-out language. It was this powerlessness that Andrzej Wróblewski tried to overcome, as though he had been aware since his youngest days that the necro-performance of real war, acted out on a scale of one to one, could not be translated into a two-dimensional picture. One of the earliest attempts at using an implied gesture of powerlessness was his 1948 painting Blue Chauffeur.

‘A Difficult Age. Szapocznikow – Wajda – Wróblewski’, exhibition view at Mo Museum, photo courtesy of MO Museum / Norbert Tukaj

The chauffeur is indeed blue, just like all the dead figures in his later paintings. The windows of his light blue cabin show an outline of a road drowned in all-embracing white. And a red horizon. At first glance then, it is a phantom bus, a vehicle of the dead heading towards conflagration. We are given a vision of driving facing backwards; we are viewing it, or participating in it, while standing – like the artist himself – immediately behind the dead chauffeur’s back. And travelling with him into the afterworld. Soon afterwards, the artist used a prewar black-and-white photograph as his model for painting a multicoloured car, a spectre from the past, a backdrop for the yellow phantom of a man that may be the artist’s self-portrait, inserted to replace his deceased father. This type of ‘mystical’ identification with the dead brings the act of painting close to an actor’s embodiment of a role while suggesting his own, separate existence ‘outside the frame’, in the stance of an observer.

This duality of vision is characteristic of many of Wróblewski’s paintings. The shadowless victims of the Executions may be what the witness’s eye pupil had retained in its memory before the living became dead. The second Execution, later designated no. VIII, and often referred to as ‘surrealist’, is perhaps the most striking in the series, broken down into the various stages of a living person’s metamorphosis into a dead one. As used in this painting, the left-to-right ‘time lapse’ sequence seems to be meant to extend the ‘afterimage’ of the execution in time: from the moment of anticipation, through the stages of a person’s transubstantiation (impossible to capture from the outside) into a deformed phantom levitating above the ground, and an ‘astral body’ departing into non-existence. It would then have been an attempt to capture in a painting that elusive instant when someone is no longer alive but still not entirely dead. The idea was thus not to portray dead people but to convey the very process of dying, to illustrate the phenomenon of the metamorphosis of organic matter, the transformation of an entity into an object – something that also occupied Alina Szapocznikow’s mind in the final period of her work. Much like Wróblewski in his paintings, the sculptress pointed to the ‘memory’ of garments retaining the shapes of the body that had still been alive just moments previously.

The somewhat later Execution against a Wall depicts two figures extracted from two different realities, even though set against the same redbrick wall. A completely dressed, intact (‘eternally living’?) personage in a red necktie is juxtaposed here with the already contorted, barefooted figure of a dying blue man. This characteristic twisted contortion of the body was to be repeated by Zbigniew Cybulski in the final scene of Andrzej Wajda’s Ashes and Diamonds. In Wróblewski’s work we see the hero and the victim as two different individuals; in Wajda’s film they merge into one tragic hero-victim figure doomed by history, marked by Fate.

‘A Difficult Age. Szapocznikow – Wajda – Wróblewski’, exhibition view at Mo Museum, photo courtesy of MO Museum / Norbert Tukaj

One of the questions prompted by Wróblewski’s oeuvre would be about the position from which we are supposed to view some of the scenes, as this is a decisive factor in the painter’s adoption not only of his own vantage point, but also of the one he intends for the ‘external’ onlooker, on whom he imposes a dual role: that of a viewer of the picture and an observer of the execution. Only in the first Execution (‘with a Gestapo man’) can we see the figure of the executioner; the painter (and the viewer) are standing behind his back.[3] All the other scenes are depicted frontally, from the perspective of the perpetrator, as it were, or someone positioned near him, in the same line. In The Polish Theatre of the Holocaust[4], Grzegorz Niziołek invokes Hannah Arendt’s concept of bystander, an incidental onlooker entangled in the spectacle of death without being involved emotionally. Such an observer does not get close to the victim, remains ‘outside’, and therefore refuses to take any burden on his conscience. Such bystanders have formed the groups traditionally gathered at execution sites since time immemorial, including those during World War II in occupied Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Belarus and Ukraine. Through his pictorial composition, Wróblewski seems to reduce the distance between the viewer and the victims. In this way we land in direct proximity to them, which makes it difficult for us to see the background, and we cannot even quite fit the whole painted figures into our field of vision – as is the case with the first Execution, where the perpetrator’s head is out of our sight, and with both mother-and-child pictures, where the frame truncates the mothers’ heads. This dramatic proximity makes us participants rather than viewers of the tragedy. This means no more than that the artist has placed himself in a similar position. He is neither a detached bystander nor an incidental onlooker. He goes deeper; in some scenes the closeness to the victims is almost palpable, and therefore this palpability should also extend to the viewer looking at the painting. Sucked into the tight frame, we lose both our distance and our sense of security; we become participants of the tragedy and accompany the victims in their process of dying.

Such was the past experience of Alina Szapocznikow: first in her individual private life, when she lost her ailing father, then in the ghettos and camps, where dying and killing were inseparable elements of the everyday; perhaps this is why the sculptress never conveyed her memories, nor did she speak about them directly in her works. Wróblewski, whose only such direct experience had apparently been the sudden death of his father, was probably protected from the sight of executions by his mother and elder brother, but then again the acts of genocide in Reichskommissariat Ostland, which Lithuania was part of, did not take place in public.[5]

‘A Difficult Age. Szapocznikow – Wajda – Wróblewski’, exhibition view at Mo Museum, photo courtesy of MO Museum / Norbert Tukaj

When considering his early paintings, it is worth going back to the first work in this series. Its subtitle (‘with a Gestapo man’ or ‘with an SS man’) was not added by the artist. Using the general concept of ‘Execution’, Wróblewski not only elevated it to a more universal level but also drew attention to the act itself rather than the perpetrator, as though deliberately wishing to marginalize his identity. This supposition emerges only upon a careful expert analysis of the cut and colours of the uniform and the form and placement of the pistol holster. It goes to prove that we are dealing here with neither an SS man nor a Gestapo man. Painted with some precision, the details, such as the green shirt, the navy-blue breeches, or the holster of raw hide tailored to the shape of the Nagant, are the closest to the regulation uniform of a Red Army officer in the military NKVD units known as Smersh. They made themselves known after the German forces were pushed out of Vilnius.

The city was liberated by the joint forces of the Home Army (AK) and the Red Army on 13 July 1944. Just four days later the Smersh units began to arrest and disarm the Home Army troops.[6] The same was done throughout the territory of the prewar Republic of Poland. Some of the combatants were incorporated into the incoming forces or blackmailed into cooperation. Andrzej Wajda devoted his film The Ring with a Crowned Eagle (1992) to one such case. The protagonist, manipulated by Polish officers of the new Office of Security (secret police), which collaborated with the NKVD, ‘delivers’ his underground commanders to them in good faith.

Smersh units did not conduct street executions but its soldiers did kill people during hunts for ‘collaborators with the fascists’ in the streets, courtyards and alleyways of many towns, and in prison torture chambers. There is no knowing whether Wróblewski was an incidental witness to such an act in Vilnius, but he must have been well oriented in the cuts and colours of the uniforms of both German and Russian formations – especially those that brought death to the civilian population and inspired widespread fear. A not so recent memory may have come back to him in 1948, with the increasingly common knowledge of the trials and executions of members of the Polish underground forces conducted in Poland with the considerable assistance of the NKVD and Smersh units. The trials were covered by the state newspapers, which discussed the events from the ‘orthodox’ point of view, but speaking one’s mind about them in free public discourse was out of the question. This may be why the artist gave his painting a title with broader scope, which, ‘just in case’, was assigned a safely narrower interpretation after his death (probably by his mother).

‘A Difficult Age. Szapocznikow – Wajda – Wróblewski’, exhibition view at Mo Museum, photo courtesy of MO Museum / Norbert Tukaj

***

The Academy of Fine Arts, to which Wajda was admitted one year after Wróblewski, did not live up to his expectations or satisfy his ambition. Years later he would reminisce, on numerous occasions, about his visits to his fellow student’s studio and the impression that the Executions had made on him. One of his reasons, as he later claimed, for transferring to the film school was his conviction that he would never surpass his fellow student’s achievement as a painter. It would therefore appear that he largely devoted his directing studies to finding means of expression which would enable him to achieve, in the language of film, a power of persuasion comparable to that contained in Wróblewski’s paintings.

His years of study at the Film School in Łódź coincided with the apogee of Stalinism. His fellow students included a number of the future most prominent Polish directors, credited with creating the so called Polish School. Some of these artists had been soldiers, some members of the underground forces during the occupation. They all reflected upon the entangled complexity of their homeland’s history. Wajda shared with them the same wartime trauma, memory of occupation hardships, and difficult transition into the post-war reality. He was, however, the only one to devote six of the eight feature films that he made during the first decade after his debut to the theme of war, and four of these account for all of his youthful output (1955-59).

His debut film, Generation, was made in 1954, i.e. after Stalin’s death, but still under the close observation of party functionaries. This is why Wajda moved the persuasive qualities of the film from the screenplay to the visual stratum. Tadeusz Janczar, the director’s peer, cast in the role of Jasio Krone, was made-up, combed, and dressed in a light-coloured Burberry-style trench coat, just like Humphrey Bogart in Casablanca. Visually attractive and resembling the idol of the international audience, he represented a world of different values, and the tragic figure of Jasio became a ‘desirable alter ego’ for many of his peers, possibly even for Wajda himself. Krone lost his fight and had to die so that those who survived would speak on his behalf – a message that can be deciphered in that first film already, and one that Wajda was to include in many of his subsequent works.

‘A Difficult Age. Szapocznikow – Wajda – Wróblewski’, exhibition view at Mo Museum, photo courtesy of MO Museum / Norbert Tukaj

Wajda used a similar ploy involving the subliminal influence exerted by the main character’s image in Ashes and Diamonds (1958), whose protagonist was a young Home Army soldier, Maciek Chełmicki. In this case, the intended type was that of a boy resembling James Dean – an American movie star. Tight trousers, unbuttoned shirt, leather jacket, thick-soled boots. This is what defiant boys in the People’s Republic wanted to look like. In Ashes and Diamonds Wajda gave them their own indigenous rebel, Zbigniew Cybulski. Maciek Chełmicki is no longer a Home Army soldier performing his last mission in 1945; he is a modern hero through and through, speaking and acting like young people in 1957. Which is why none of those viewing the film engages in any subtle discourse of consciousness and conflicting reasons; everyone is on one side: that of the doomed lone desperado, torn by dilemmas.

The premiere and tremendous worldwide success of Ashes and Diamonds coincided with a major posthumous retrospective of Wróblewski’s work, prepared with Wajda’s participation, revealing for the first time the painter’s real achievement (even though not all of his oeuvre was shown), which, however, did not result in international recognition. This lack of understanding of the greatness of his friend’s work may have been one of the reasons why, on the tenth anniversary of the artist’s death, the director arranged another exhibition of selected Wróblewski paintings. This time he incorporated it into the narration of his film Everything for Sale[7], otherwise devoted to the memory of Zbigniew Cybulski (who had died a tragic death in January 1967). The auto-thematic formula of this ‘film about filmmaking’ enabled Wajda (epitomized by the director character played by Andrzej Łapicki) to ‘see himself’ as an artist entangled in a memory of war and a memory of friendship with other artists entangled in similar obsessions. Another phantom vision that haunts him are fragments of Wróblewski’s paintings seen in an exhibition. In the final dialogue his wife asks him: ‘Did you go to that exhibition because Wróblewski is dead too?’ A hidden stream of his thought may have also flowed towards Alina Szapocznikow, alarmed by the ‘March events’ of 1968[8], which were something not to be mentioned in public. One of the female characters takes up the sculptress’s widely-known directness in matters of sex and reveals her need for love by exclaiming: ‘Love me, all of you!’ She also takes part in the sequence involving a table with a secret hiding place under a detachable top, pointing indirectly to the possibility of using such ‘hiding places’ again, which is a clear allusion to the contemporary situation of Jews in Poland post-March 1968. Another significant sequence is that depicting the merry-go-round[9], which, in the final shot, is but a phantasmagorical ‘afterimage’ watched from afar by the director character.

‘A Difficult Age. Szapocznikow – Wajda – Wróblewski’, exhibition view at Mo Museum, photo courtesy of MO Museum / Norbert Tukaj

The merry-go-round plays an important role in several Wajda films, starting with Generation, where, in keeping with the facts of the wartime reality, it is set just outside the wall of Warsaw’s burning ghetto. The protagonists and the inhabitants of the ghetto are witnessing the behaviour of the bystanders who, during a visit to an amusement park, become an audience watching the pacification of the Jewish quarter. This sequence points our attention to one of the possible interpretations of Wróblewski’s Executions: we, the viewers (unseen, invisible witnesses to the execution), are looking at the victims but, given that they are also looking at us, we cease to be unseen, incidental passers-by, because our behaviour has been subjected to evaluation by ‘the other party’.

It is also possible to spot here a clear reference to two poems written by Czesław Miłosz in 1943: ‘Campo dei Fiori’ and ‘A Poor Christian Looks at the Ghetto’. Wajda could not cite them as reference, however, because by the time he started work on Generation, the poet had become an outlawed exile. And he omitted the theme in Samson (1961), adopting instead the point of view of a protagonist hiding in a basement on the Aryan side during the liquidation of the ghetto. The director did, however, revisit the motif of the merry-go-round in Everything for Sale, and also, many years later, in Holy Week (1995). Less well known and less popular than others, this film could be considered a contribution to the debate on the visibility[10], or perhaps invisibility, of the Holocaust, and thus the dilemma between getting close to the victim or remaining ‘outside’. The film’s female protagonist goes back to the burning ghetto after receiving no help from any quarter and her temporary protector has died at the hands of unknown executioners. The bottom line is clear: heroes die.

Writing about society’s perception of the war, and in particular the Holocaust, Grzegorz Niziołek introduces the concept of ‘theatre of war’ not only with reference to its conventional representation on stage. Transposing theatrical terminology onto the realities of the actual occupation, he enumerates the roles to be played by a community overtaken by war. On that stage, one person plays the role of executioner, another that of victim. The audience is composed of viewers. Mostly bystanders. Among them, however, is someone who has the desire to give testimony, like a photojournalist capturing the inflicting of death, where the time between the opening and the closing of the lens shutter is sufficient for the living to become dead. It may also be a documentalist performing his duties in a very small, confined space, such as the prison cells and yards where real executions took place. On the ‘stage’ of Wróblewski’s paintings, with one exception, there are only victims. An invisible audience fills the auditorium. The perpetrators are invisible too, as is the artist himself, who directs the audience from the wings, frustrating their ability to assume the position of Hannah Arendt’s incidental bystanders.

‘A Difficult Age. Szapocznikow – Wajda – Wróblewski’, exhibition view at Mo Museum, photo courtesy of MO Museum / Norbert Tukaj

The various Executions and their derivatives do not just represent attempts to find an adequate persuasive visual language for the subject of war and what it entails. The paintings in this series form a sequence of ‘curtain raisings’, or rather gestures, to invoke Agamben, each resembling a frozen scene of a theatre production or a still frame in a film, taken out of a longer narrative and placed before the viewer’s eyes as more significant than all the others.

What is almost certain in the case of many of the characters in Wajda’s films is a matter of guesswork with Wróblewski. We don’t know whether any of the painted figures represents the artist’s imagined alter ego even though he endowed many of his painted figures with his own features, known for example from his Self-Portrait (‘against a yellow background’).[11] We may, however, have the impression that the similarity of the painted victims to their painter is a ploy knowingly implying the eventuality of playing a similar role, or of taking into consideration the possibility of finding himself in the position of those being killed. We also encounter here the same handful of characters; we recognize the men, the women and the boy, but we will not know who they really represent. Besides, they are all dead. They have been summoned from ‘the other world’ so that we can commune with them.

After painting the Executions Wróblewski seldom revisited war-related subjects openly. Starting in 1955, however, he painted several series in which the presence of death was marked in a different way than in his previous works. One such is the painting Mothers – a perfect figural composition with a sophisticated colour scheme, referencing the artist’s private life: there is a small child in the foreground, and a young woman breastfeeding a baby in the background. What is somewhat unnerving is the manner in which the other woman is depicted, placed centrally in the middle ground, seated on a chair with her eyes closed.[12] Asleep? Mortified? A grey-blue shade, applied in distinct impasto on her forehead, enshrouds in light mist and slowly takes possession of the woman in the background as well: it changes the hue of her face, neck and arms, in which she is rocking the baby; as in coffin portraits depicting deceased people as though they were still alive, or balancing on the border of being ‘still alive but also a little dead already’, except that different painterly means are used here.

‘A Difficult Age. Szapocznikow – Wajda – Wróblewski’, exhibition view at Mo Museum, photo courtesy of MO Museum / Norbert Tukaj

In Laundry, the woman figure standing in the centre is truncated by her head being blocked from view by a cloth that she is hanging on a string. The other figure, compositionally situated somewhat further away, though oversized in relation to the ground in which she is placed, is a bulky woman sleeping on a chair – as though transferred here from Mothers. Her face and neck are marked with distinct light-blue shadows; she is ‘touched’ with death, as if she had been pulled out of some other reality and is supposed to represent a phantom crouched in a shaded recess, a phantom of someone who remains only in the artist’s imagination, and of whose presence the headless heroine of this scene, hanging up her washing, is unaware.

Sketched and painted a number of times, the figure of a woman asleep on a chair, or actually grown into the chair, also appears as a materialized phantom from a dream in the script that the artist wrote for the film Waiting Room.[13] Once established and scripted for several characters, the motif also featured in The Queue – a painting depicting motionless ‘chaired’ figures. Transferred into the reality created by the artist, they are devoid of life ‘by definition’, as it were; the arrow that points the direction for the queue leads into the space outside the edge of the picture – to nowhere. The vehicle driven by the phantom driver (Blue Chauffeur) – revisited by Wróblewski in 1956 – is also headed towards nothingness.

This series of large, somewhat programmatic paintings is concluded by Lovers, a reference to his 1949 series. As opposed to those earlier works, in this painting the woman is being overtaken by blue death as well. That the use of blue is again not merely a painterly ploy but a continuation of the designation of the process of departing into non-existence is indicated by the way in which the figures are painted and aligned: the naked blue body of the young woman is outlined clearly under the cursorily and abstractly sketched dress; her left hand is already locked in a dead man’s grip, her right is raised in a gesture bidding farewell to us viewers. We are parading before the picture; they are immobilized in a still frame frozen on the border of life and death. It would therefore appear that only this late painting offers a concluding statement complementing the delicate suggestions on the continual ‘infection by death’ ingrained in the previously mentioned works, showing seemingly peaceful ‘genre scenes in interiors’. The memento of these paintings was to be amplified in the subsequent – final – months of the artists’ life.

‘A Difficult Age. Szapocznikow – Wajda – Wróblewski’, exhibition view at Mo Museum, photo courtesy of MO Museum / Norbert Tukaj

At the very beginning of the political ‘thaw’ in 1956, Wróblewski spent the first three weeks of November travelling around Yugoslavia. He met with local artists and writers, and visited exhibitions, galleries and churches, but his memories of the trip as shown in his paintings focused exclusively on the singular form of local Orthodox tombstones. He rendered them in a great number of sketches, works on paper and on canvas, as though he had been enchanted by this new possibility (and form) of depicting death; one of them features a dual leg disconnected from its torso, which may have been one of Szapocznikow’s inspirations to make a plaster cast of her own leg.

The ‘tombstones’ were made in parallel with the translucent afterimages of Hiroshima victims filling Wróblewski’s canvases and sheets of paper, which were echoed not only in Szapocznikow’s Exhumed but also, years later, in the form of the bandaged mummy into which she turned her sculpture devoted to the memory of the victim of early space flight Vladimir Komarov (Weightlessness. Homage to Komarov, 1967).[14] Even more interestingly, these ‘bodiless’ figures seem to have their own, often quite comical lives in Wróblewski’s paintings, and this makes them a far cry from the customary propagandistic pathos in which artworks commemorating or reminiscing on the Japanese tragedy of 1945 were (and still are) made. One might have the impression that such a swift ‘evaporation’ from the world of the living may have been an attractive eventuality for the painter.

The third theme interwoven throughout those final months of Wróblewski’s life was studies for a male portrait, of which he made several. Only one of them is full length, penetrating the body’s interior.[15] The other ones are busts or heads, at first exercises in the use of colour and purely painting solutions, and subsequently transformed into wraith masks – skulls – as though the painter had come full circle to the point at which his artistic path had begun in 1944.

‘A Difficult Age. Szapocznikow – Wajda – Wróblewski’, exhibition view at Mo Museum, photo courtesy of MO Museum / Norbert Tukaj

As mentioned before, Wajda’s film debut contains the bud of an idea that he developed in many of his later works, as though he could not shake off some fixations and obsessively returned to them, constructing various self-commentaries and subtexts, or perhaps ‘appending’ digressions, much as Marcel Proust did to the manuscripts that formed his seven-volume reflections on lost time. Initiated by Aleksander Ford in Border Street and merely touched upon in Generation, the theme of descending under the ground in order to give freedom to someone or find it for oneself was to evolve into a multilevel allegory in Kanal, where we find not only connections with the phantasmagorical roaming through Dante’s Inferno, but also the whole national exposition of the Polish fate that is present both in Mickiewicz’s Forefathers’ Eve[16] and in the work of Wyspiański, who has already been mentioned here. This is no longer theatre being acted out on the stage of an isolated wartime episode, but total theatre, unfolding on the pages of history. Its main protagonist is the Polish Fate embodied in heroes dying in mazes without exit. The blinded Jacek who dies laid on Stokrotka’s lap, reproduces the form of Michelangelo’s Pietà, becoming the Polish Christ, and like Maciek Chełmicki in Ashes and Diamonds, entangled in blood-soaked sheets – shrouds – and consigned to the rubbish heap of history.

The latter theme became dominant years later, in Pilate and Others (1972). The action is set in Nuremberg – the city of the Nazi Parteitage and the postwar trials of war criminals. Wajda would reminisce years later: ‘This pseudo-Rome was an ideal setting for Pilate, providing an ironic commentary on the brief history of the alleged “thousand year” Reich, whose rapid collapse I saw with my own eyes.’[17] This is where Pilate judges Jesus.

The staging of the way of the cross is not, however, taken straight from Bulgakov’s novel[18]; it is rather a visualization of Father Piotr’s vision in Forefathers’ Eve by Mickiewicz[19], developed by the director in a number of drawings made on the reverse sides of the shooting script pages. Differently, however, than in Forefathers’ Eve, and also differently from Bulgakov’s description, Wajda’s Golgotha is a huge heap of rubbish, an allegory referring no longer merely to Poland, as it did in Ashes and Diamonds, but to the whole of the Euro-Atlantic civilization with its rational manner of meting out justice applied to the dehumanized criminals, who had relapsed into savagery – and also to his personal experience, elevated to the rank of symbol: ‘I remember well two public executions during the Nazi occupation. Both took place at the entrance to the city, near large factories employing thousands of workers; who on their way to work and back had to pass by the gallows standing by the roadside.’[20]

‘A Difficult Age. Szapocznikow – Wajda – Wróblewski’, exhibition view at Mo Museum, photo courtesy of MO Museum / Norbert Tukaj

In this way, wartime memories gain a presence in a film that is not about the war, just as they are permanently present in Everything for Sale. Transferred from that work and reused in Pilate and Others, the narrative ploy that places the action in two-tier quotation marks, in a film about filmmaking, makes it possible to cast in bold relief the overall theatralization of the original spectacle, which in fact refers less to Bulgakov’s prose than to the perennial practice of marginalizing someone else’s suffering. Wajda first draws the stage and proscenium of an ancient theatre at close range, and then pans out to capture the whole panorama of the city with the stadium in the foreground. Another level of the film’s frame of reference is its disturbing prologue, saturated with flash views of an abattoir, in which Andrzej Wajda himself asks the ram – the leader of the flock – about his responsibility for leading others (the sheep) to extermination. The ram’s horns are painted red, which is supposed to dispel any potential analogies to the figure of Jesus and point the viewer’s attention towards the communist regime. But from today’s perspective we may allow ourselves an attempt to read into this scene the iconoclastic intentions of Konrad’s ‘Improvisation’ (‘…you are not God but… czar’) in the same Forefathers’ Eve by Mickiewicz. And, indirectly, a reference to both Gustaw Holoubek’s famous role in Kazimierz Dejmek’s 1967 production of the play, together with its political consequences, and the events of December 1970, after which no one was held guilty of shooting on the defenceless crowd of protesting workers. Which is why the title of the film is not confined to Pilate but there are also unnamed ‘others’ who continue to deliver untried suspects into the hands of a hate-drunk mob or sentence people to death and wash their hands of all responsibility.

The message of the prologue in Pilate and Others was to be amplified by the scenery comprising a bridge over railway tracks and a ramp. This motif was to emerge years later in Korczak (1990), The Ring with a Crowned Eagle (1992), and Katyn (2007). The first gives a panoramic view of the Umschlagplatz in Warsaw during the dispatch of Jews deported to Treblinka; the second shows Home Army soldiers and officers kneeling on the platform waiting for the train that will take them to Soviet prison camps; the third depicts Polish commissioned officers on their way to Katyn. Like the motorcar in Wróblewski’s work, for Wajda the train becomes the 20th century’s horse of the Apocalypse, taking heroes away to meet their Fate.

Images of great persuasive power, which can be seen in as early a film as Generation, also ‘act’ in his subsequent works, on a par with the actors, and sometimes – working against the screenplay, as it were – they convey subliminal messages. Quite often, just like the rubbish heaps and railway ramps mentioned before, they ascend to the rank of symbol, adding strength to selected parts of the film’s narrative. A similar function is fulfilled by scenographic elements accentuating (and in themselves amplified by the position of the camera) the dramatic quality of the ‘no-exit’ situations in which the protagonists find themselves. In Generation it is the grille barring Jasio Krone access to the roof as he tries to escape the enemy’s pursuit, and thus frustrating his chance of survival: his only way out is to jump into the dark abyss of a spectacular staircase. In Kanal, Jacek and Stokrotka, roaming the city’s underground Hades, head towards a light in the distance only to find themselves barred by a metal grate flooded with sunshine, through which the girl can see the other bank of the Vistula – a rescue beyond their reach. By that time Jacek has gone blind and is about to die, believing that their roaming has come to an auspicious end.

***

‘A Difficult Age. Szapocznikow – Wajda – Wróblewski’, exhibition view at Mo Museum, photo courtesy of MO Museum / Norbert Tukaj

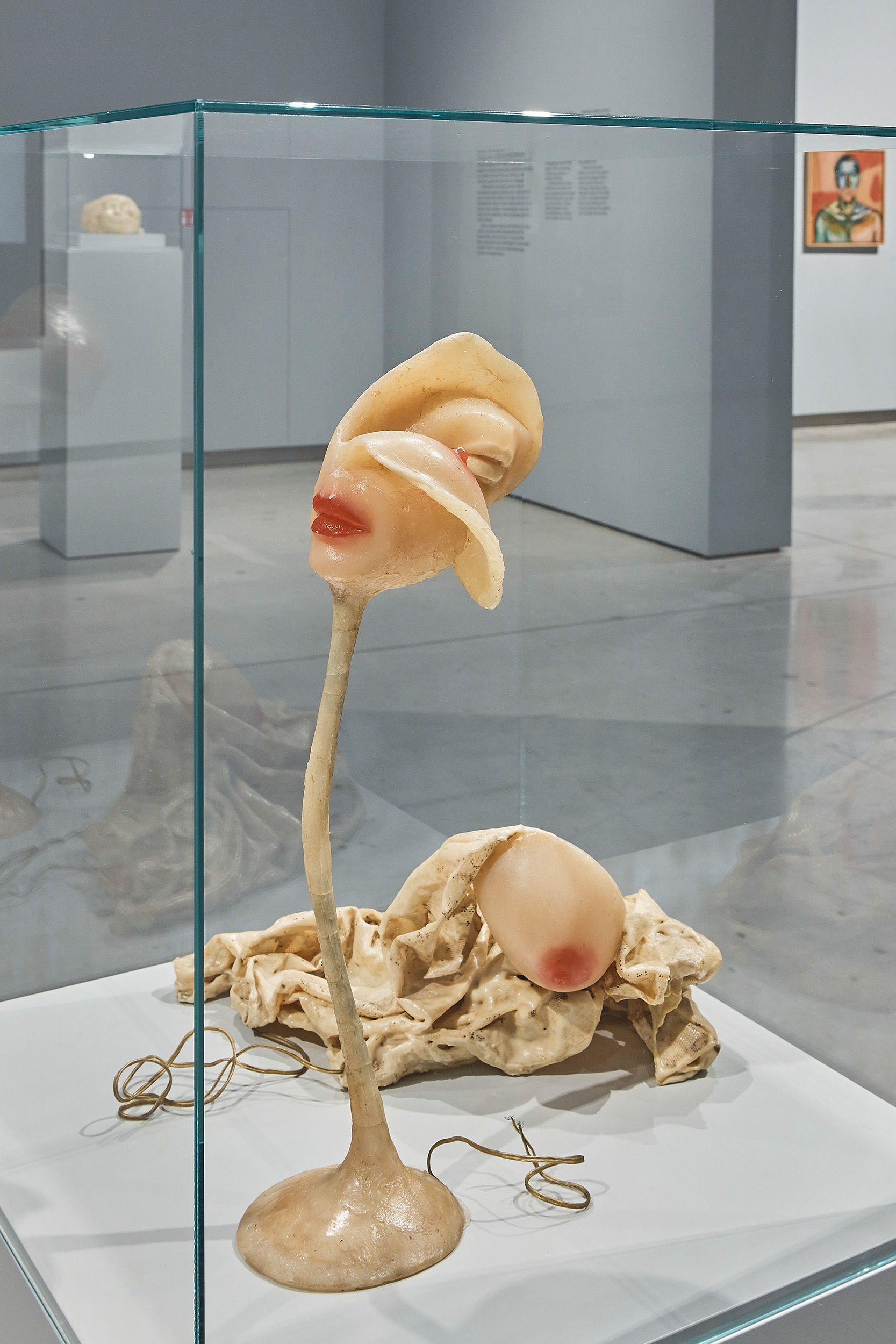

In 1947 Georges Bataille’s booklet L’Alléluiah came out in Paris. Being one of the few of his essays that were published relatively soon after being written[21], it must have attracted considerable interest, especially if we consider the fact that it was illustrated with eighteen female nudes by Jean Fautrier. The work of the French artist and Resistance fighter was beginning to gain popularity at the time; his first postwar exhibition was opened in the prestigious Galerie René Drouin as early as 1945. Such an intimate mode of expression in statements about the war, devoid of any pathos, was a major novelty in postwar Europe and soon became the object of many French critics’ and artists’ analyses. It must have stirred Parisian students as well. Szapocznikow was to recall that series and other works by the French artist – only after 1954. Such works included two almost realistic sculptures relating to adolescence: First Love (1954) and Difficult Age (1954-55), in addition to one fundamentally different in both expression and message – Exhumed (1955-56).

Despite her stubborn silence with respect to her wartime experience, the artist did give vent to her memories. She did so indirectly, invoking supra-individual concepts and more universal forms, for example in the sculptures in the Monster series, which represent crippled, deformed male bodies impaled on metal rods in a manner that makes the latter look not like structural elements but rather like implements of torture. During that time Szapocznikow conducted experiments with new technologies, and also created small sculptural forms made of lead, possibly as studies for later sculptures – more definite in their disintegration and their singular eroticism.[22] Both disintegration and eroticism come to the fore in a series of perversely titled female figures, rendered in increasingly durable materials: Mary Magdalene with a phalloid head, Bellissima I, Bellissima II, and Woman-Rose. The way these figures are approached again betrays similarities to some of Fautrier’s sculptures, although here a more profound, perverse lure of crippledom is intended. Torn apart and sewed back together, as it were, out of remnants of matter, Szapocznikow’s sculptures resemble a female version of Frankenstein’s monster, driven solely by sexual urges. This may be what, in the artist’s mind, the transition from girlhood to adulthood was like in the context of her wartime experience. In the external – i.e. purely formal – perception, these torn, mutilated, and actually dead sculptural figures fitted perfectly into that time’s paradigm of modernity. And this must have also been the line of reasoning followed by Andrzej Wróblewski when he included Bust[23] in his final ‘tombstones’.

In 1964, a position similar to ‘chairing’ was featured in Alina Szapocznikow’s work; it was connected with the concept of ‘personifying’ used by the artist in the context of two of her sculptures that have not survived to our time.[24] Both are made up of fragments of a totalled car, whose exhaust pipes penetrate the mass of plastic cement, forming monstrous fusions of chair and flesh. Such integration of flesh and machine is also a characteristic of several other sculptures made with the use of car parts, fused with formless ‘fleshy’ matter. She followed a similar practice in creating various crippled mutant figures, notably Goldfinger, a sculpture representing gilded female leg stumps growing upwards from a crotch sealed with a car’s suspension spring. If one considers her experience of ‘machine violence’ in day-to-day camp life, one cannot help the impression that the euphemistic or vaguely referential titles of these works were meant to prevent potential associations with her wartime past and conceal their actual meaning. Possibly from herself. The only option left was to view them externally, something to be considered in terms of re-re-presentation: machine-as-sculpture-as-body. This applies in particular to his obsessions relating to the hypersensitive phase in the development of a human being, which, in her specific case, could be described as ‘infection with death’, remembered – and actually even archived – by her body.[25]

‘A Difficult Age. Szapocznikow – Wajda – Wróblewski’, exhibition view at Mo Museum, photo courtesy of MO Museum / Norbert Tukaj

The artist admitted to making a self-portrait only after preparing a cast of her own leg. In this case, her personal presence in her work is marked not only by the cast of her face but also by one of her foot – the part that can be seen on a day-to-day basis, which we do not conceal under our clothes, which we do not shield but which points our mind towards the areas of our body that are hidden from view. Because, in keeping with Bataille’s L’Alléluiah, concealment from view underscores the dark, sinful, ‘filthy’ attractiveness of the intimate parts of the body.

Soon, however, ‘impressions’ were also taken of these ‘sinful’ breasts, buttocks and bellies, thereafter to be multiplied and dispersed, to become objects in themselves, but also building material for other sculptures. A body dismembered, continuously incomplete, pieces taken out of a whole, reduced to the function of gadgets, an object – a fetish in which the artist’s presence, or rather the presence of her body remembered by the material, is multiplied and released into circulation. Displaying fragments, however, revealed the meaningful sphere of shortage and deficiency, and evoked thinking about such concepts as integrity and completeness, which had been removed from view. The work that speaks, or rather screams, of this incompleteness in the loudest voice is the polyester flesh-like Headless Torso, sunk into the formless matter of black polyurethane, a toxic, carcinogenic and impermanent material, in which another sculpture, Plongée, was drowned nearly literally, as was Stéle, with exposed knees and a black-smeared mouth. This series was made soon after the antisemitic campaign by the Polish authorities initiated in March 1968. Marek Beylin claims that the artist decided never to return to Poland after the events of March 1968.

Towards the end of the same year she was diagnosed with breast cancer and started working on the Tumours, Fetishes, and Lamps. She made them alternately. Fetishes and Lamps are built out of casts of her breasts and buttocks, as if the artist desired to extend her existence beyond the edge of life. Draped in crumpled soft fabrics sunken in polyester, these sculptures resemble Wróblewski’s empty garments, ‘remembering’ the shapes of the executed bodies.

‘A Difficult Age. Szapocznikow – Wajda – Wróblewski’, exhibition view at Mo Museum, photo courtesy of MO Museum / Norbert Tukaj

Comparisons with the painter’s work seem obvious even at the level of the most general meaning of trauma and ways in which it can be transposed into works of art. When considering the practice of body fragmentation – involving the use of different means in each case, by the way – it is worth noting one of the major factors shared by these works: both the remnants of the executed in Wróblewski’s paintings and the fragments of a woman’s body, severed from the whole and multiplied in Szapocznikow’s sculptures, have a similar ontological status: they represent not-living. The corpses – which in one case take on the form of phantoms of a living body, obscene in their nude exposure, and whose formlessness in the other is often dressed in decent clothes – take part in a kind of necro-performance.[26] In Szapocznikow’s work, they bedazzle with nudity, rest on erect phalluses as Mad Fiancées, preen themselves with the remnants of the bodies sewn together. In Wróblewski’s pieces, they attempt successive stagings of their passage ‘into the afterlife’; they pose for pictures of real life or simper from their own tombstone effigies; they even become objects of museum exhibitions. All the characters in this theatre of spectres, despite their deadness, repeat the incantation that accompanied the hundreds of the living who tried to leave to posterity a testimony of what they had experienced: ‘Non omnis moriar! Not all of me will die.’

The Tumours – blown-up and multiplied polyester ‘portraits’ of the alien tissue eating up her body and yet dissociated from it, externalized and placed before the eyes of anyone who would wish to view them – are part of a somewhat different regime within Szapocznikow’s oeuvre, but they do contain the same relentless ‘Not all of me will die.’ Going back in some of them, at least to some extent, to the necro-performance of war, the artist sank in them enlarged photographs from the dead victims of one of the extermination camps, taken from an illustrated book. Faces of young, beautiful, living women, also cut out of magazines, are ‘hugging up’ to them. Szapocznikow also made a more personal Souvenir: a small ‘shield’ of polyester into which is sunk an enlargement of a prewar photograph of herself with her father. Placed under the hard coating of the transparent substance, it is one element of a collage which also includes, among other things, one of the most drastic camp photographs. The little Alina’s bare foot is pointed at the open mouth of a dead body.

In this way, for the first time openly and publicly, the artist not only brought up the memory of the camp victims but also made a reference to her personal past, revealing what she probably saw ex post in all its cruelty: her being doomed to a degrading death amidst the nameless mass of many just like her, contaminated, stigmatized, and defenceless. The fact that she had survived did not remove from the horizon of her thoughts the very fact of being condemned too, i.e. of potentially sharing the fate of millions of those whose remnants enriched the soil of hundreds of towns in the bloodlands described by Snyder, somewhere between Babi Yar and Ponary and Bergen-Belsen, Buchenwald and Flossenburg.[27] This is the soil from which the Herbarium grew, her last multi-part work: distorted, almost two-dimensional remnants of what had once been a human being, tossed onto the surface of cheap plywood like withered skin sloughed from a dead body.

***

‘A Difficult Age. Szapocznikow – Wajda – Wróblewski’, exhibition view at Mo Museum, photo courtesy of MO Museum / Norbert Tukaj

Seven of the eight Executions, much like all the ‘mothers with children’, remained hidden in the artist’s studio until 1958, when two posthumous Wróblewski retrospectives were held: first in Kraków, then in Warsaw. The artist’s mother took part in preparing both. It was she who decided what should be the obverse (recto) and what the reverse (verso) with respect to the canvases painted on both sides. She also gave titles or subtitles to most of the paintings on canvas, in addition to annotating and dating her son’s works on paper. The task of reproducing the real chronology of the creation of these pictures, based on the artist’s own notes, was only undertaken by Anna Król as part of her work on a retrospective of Wróblewski’s oeuvre curated by Hanna Wróblewska at Warsaw’s Zachęta Gallery.[28] On that occasion, a number of unclear biographical details were clarified by Marta Tarabuła, who had just published her book Wróblewski nieznany (Wróblewski Unknown)[29], which comprised the first attempts at reinterpreting the artist’s work. While his oeuvre has been the subject of specialist analyses ever since, some aspects of it remain unelucidated. We still know least about the Vilnius period of Wróblewski’s life, which is also the case with regard to the early years of Alina Szapocznikow, and even those of Andrzej Wajda, who lived by far the longest of the three. This is why many interpretations have to rely primarily on the historical events and facts that provided the backdrop to their individual biographies and shaped the overwhelming circumstances of their adolescence.

Vilnius was not spared the atrocities prevailing in all the areas overtaken by war. Much like everywhere else, local Jews were being particularly persecuted during the Hitler occupation. About 13,000-18,000 of these were murdered between the Wehrmacht’s entry into Vilnius on 24 June and early September 1941.[30] The Jewish ghetto was officially established in September 1941; on 1 January 1942 a Jewish partisan organization was formed there, and proceeded to prepare an anti-German uprising. It was scheduled to start in July 1943 but its outbreak was actually prevented by the residents of the ghetto. Some of the partisans managed to leave the city and fight their way into nearby forests. The ultimate liquidation of the Jewish quarter took place on 23-24 September 1943 but the extermination process continued for much longer.[31] Executions were carried out in Ponary (Lith. Paneriai), a summer resort outside Vilnius which the Russians had converted into a military fuel depot. The trenches that they dug were later used by the Germans for mass graves. The Vilnius Sonderkommando had 150 Lithuanian members, mostly Shaulists.[32] They formed the ‘Ponary shooters’ headed by SS-Hauptscharführer Martin Weiss.[33] According to the sources, about 100,000 people died there between July 1941 and July 1944. Stories of these executions can be found in the recently published diaries of Kazimierz Sakowicz.[34] Andrzej Wróblewski was probably not familiar with these accounts, but he may have come into contact with a copy of the periodical Orzeł Biały (‘White Eagle’), published in Rome, which contained a shocking, detailed account by Józef Mackiewicz of the ‘unloading’ of a transport at the Ponary railway station in October 1943.[35]

His reportage covers a unique event, an attempt at rebellion mounted by Jews locked in a rail carriage on a siding, who broke the windows and the doors open and tried to escape. They were massacred on the ramp and the adjacent tracks, soon to be passed by a fast train from Berlin to Minsk via Vilnius.

‘A Difficult Age. Szapocznikow – Wajda – Wróblewski’, exhibition view at Mo Museum, photo courtesy of MO Museum / Norbert Tukaj

The driver released steam to the sides, which hissed in white billows, covering the sight for a moment, and drove over the dead and wounded bodies, cutting through torsos, limbs and heads, and as the train vanished into the tunnel and the steam blew away, all that was left behind was pools of blood and dark stains of shapeless bodies, suitcases, bunches; they all lay there, similar to one another and motionless. And only one head, severed at the neck, which had rolled into the middle of the approach, was clearly recognizable as a human head.[36]

This information probably spread through the grapevine long before its publication, especially when we consider that the whole incident was witnessed by the Polish railwaymen on duty at the station at the time. Consequently, Wróblewski’s Executions should be considered in this context, which makes the depiction of dismembered, headless or bisected bodies more comprehensible. They were not just pure invention but also a product of the artist’s imagination prompted by the graphic, as one may conjecture, stories of the event.

Mackiewicz reports that afterwards the Sonderkommando took preventive measures to make sure that the situation which he described would never happen again. One of them was to tie men’s hands, sometimes using barbed wire. One of such men is shown in Liquidation of the Ghetto in the middle ground, another further in the background. This painting has been traditionally associated with the Warsaw ghetto (as indicated by one of the subtitles), although the title was not given to it by the artist himself, and despite the fact that such methods were not used in Warsaw. Moreover, Varsovian Jews were not forced to wear the Star of David sewn onto the backs of their coats, colloquially referred to as ‘patches’ – clearly visible in Wróblewski’s painting.

The same painting shows a woman holding a dead child in front of her. In Mother with Dead Child, the naked dead infant has a clear bullet mark on its back. In Execution of a Family, the child, still alive, partly shields the mother’s body. Notably, the other measure taken to prevent chaos during the unloading and the executions in Ponary was the order given to mothers to hold their children in front of them. Then they would die first. This order was probably also common knowledge, at least from the autumn of 1943, when the method used to conduct the ‘liquidation’ was no longer any secret. Wróblewski may have not seen it but he was definitely aware of it, and therefore at least a few paintings in this series refer to the artist’s memories of his Vilnius period, when he was still a boy.

‘A Difficult Age. Szapocznikow – Wajda – Wróblewski’, exhibition view at Mo Museum, photo courtesy of MO Museum / Norbert Tukaj

And once he had moved to Poland, in the summer of 1945 he travelled from Kraków to Łódź and Katowice, areas that had been incorporated into the Third Reich during the war, and he must have heard about the fate of the women who had fallen into the hands of the Red Army in those regions. The painting Child with Dead Mother is filled with a frontallyrendered silhouette of a mother and a young boy standing with his back to the viewer, wearing green shorts and a colourful sleeveless shirt in black, yellow and red stripes – the German national colours. In 1949, it was only in this way, through this peculiar use of colours on the shirt, that Wróblewski could note this aspect of the war as well. For him, just as for Wajda, Szapocznikow, and many others, the war did not end on 8 May 1945. It lasted as long as their respective lives.

***

While the work of these three artists has for years been well known to both the public and scholars in Poland, the progress of its reinterpretation remains rather slow.

The renewed insight into Szapocznikow’s oeuvre began with a large retrospective at Warsaw’s Zachęta Gallery (1998), subsequently shown at the National Museums in Kraków and Wrocław. Her return to the world art scene began with the show at the WIELS Contemporary Art Centre in Brussels (2011). Further exhibitions, at such prestigious art centres as the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, MoMA, New York (2012), the Centre Pompidou in Paris (2013), the Bonniers Konsthall in Stockholm (2013), and the Tel Aviv Museum of Art (2014), strengthened her international position.

Similarly, the large Andrzej Wróblewski exhibitions at Warsaw’s Zachęta (1995) and Kraków’s National Museum (1996) paved the way for a better examination of the painter’s work in Poland. Examination on an international scale began at the Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven (2010), which laid the groundwork for the famous exhibition Recto/Verso at Warsaw’s Museum of Modern Art (2015), subsequently shown at the Reina Sofia in Madrid (2016).

‘A Difficult Age. Szapocznikow – Wajda – Wróblewski’, exhibition view at Mo Museum, photo courtesy of MO Museum / Norbert Tukaj

Widely known and studied, Andrzej Wajda’s filmography still awaits a revised insight.

The relatively obvious biographical ‘common denominator’ shared by these three artists and friends did not attract the attention of art historians, critics and curators for decades. The earliest publication to discuss this issue at any length was published in the monthly journal Osteuropa (6-7, 2016). This was the outcome of the comparative studies that I had conducted during my fellowship at the Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin (2015/2016).

My attempts to examine the various works of each of the artists in this triad in more depth came during the preparations for the exhibition at the Silesian Museum in Katowice, which opened on 20 June 2018. In addition to reinterpreting a number of well-known art objects and films, this show aimed to decipher their hidden messages, identify common themes and interests, and also shed some light on the relations between selected works by these three artists overtaken by an obsession with war and death.

This text is an abridged version of an extended essay published in the catalogue to the exhibition Perspective of Adolescence. Szapocznikow – Wajda –Wróblewski, Muzeum Śląskie, Katowice, 2016. It was published on the occasion of the exhibition A Difficult Age. Szapocznikow – Wajda – Wróblewski in MO Museum, Vilnius, 20 March – 18 July 2021.

[1] D. Sajewska, ‘Geschichtsbilder. Prospect(s) for a Theory of Theater’, trans. J. Pytalski, View. Theories and Practices of Visual Culture, no. 10, 2015, p. 12. This is a chapter from D. Sajewska, Nekroperfomans. Kulturowa rekonstrukcja teatru wielkiej wojny, Warszawa, Instytut Teatralny im. Z. Raszewskiego, 2016.

[2] G. Agamben, ‘Notes on Gesture’, in idem, Means Without End: Notes on Politics, trans. V. Binetti and C. Casarino, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 2000, p. 5.

[3] The perpetrators are featured in several sketches; the artist removed them at the painting stage.

[4] G. Niziołek, The Polish Theatre of the Holocaust, trans. U. Philips, London, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2019.

[5] Except for the territory of the Vilnius ghetto.

[6] According to various sources, soon after crossing the prewar Polish border, NKVD units arrested about 20,000 Polish citizens whose attitude, according to the Soviet security apparatus, was hostile towards the USSR and the newly-formed Polish Committee for National Liberation (PKWN). Many of the arrested Home Army soldiers were deported deep into the USSR, where they died in large numbers in Soviet camps. From 1945, special NKVD and Smersh prisons and camps were created in Poland, the most widely known being Special NKVD Camp No. 10 in Rembertów, where the prisoners included arrested Home Army soldiers.

[7] The film was shot in winter 1968, and premiered in January 1969.

[8] The student rebellion of 8 March 1968 became a pretext for an antisemitic witch-hunt and the expulsion of thousands of citizens of Jewish descent from Poland.

[9] During a meeting with viewers occasioned by a showing of a cleaned-up version of the film, Wajda said that the merry-go-round had been cameraman Witold Sobociński’s idea.

[10] This concept is also referred to by G. Niziołek, op. cit., pp. 38-39.

[11] And another, full-length self-portrait, cut in half a few months after its completion.

[12] The eyes of the women depicted in the studies and sketches for this painting are shut as well.

[13] Łukasz Ronduda, ‘Exhibition as film: Exploring Andrzej Wróblewski’s Waiting Room scenario’, in Andrzej Wróblewski: Recto/Verso, Warszawa, Muzeum Sztuki Nowoczesnej, 2015, p. 187.

[14] The circumstances of the cosmonaut’s death and the making of Szapocznikow’s sculpture later inspired Barbara Wysocka’s theatrical production Szapocznikow. Stan nieważkości / No Gravity at the Teatr Centrala in Warsaw (2014).

[15] Existing also as a separate drawing.

[16] A. Mickiewicz, Forefathers’ Eve, Part III, Piotr Wysocki’s statement closing Scene VII: ‘…Our nation is like a lava field…’

[17] Pilatus und andere, wajda.pl (anonymous translation).

[18] The Master and Margarita.

[19] A. Mickiewicz, Forefathers’ Eve, op. cit., Scene V.

[20] Pilatus und andere, op. cit.

[21] This was preceded by the 1945 publication of Madame Edwarda with 32 drawings by Fautrier, who used the pseudonym Jean Perdu for it, while Bataille’s identity was concealed behind the pen name Pierre Angelique. Cf. E. J. de Oliveira, ‘Fautrier and Georges Bataille. The Erotic Touch of Matter’, in Jean Fautrier. Matière et lumière, Paris, Editions Paris Musées, 2018.

[22] It is worth noting here that Jean Fautrier made multiple copies of his Hostages cast in lead in the 1950s and early 1960s.

[23] Bust (Rose-Woman), monotype, 41.8 × 29.7 cm, 1957.

[24] Machine en chaire I; Machine en chaire II.

[25] Cf. D. Sajewska, op. cit., p. 12-13.

[26] See D. Sajewska, op. cit.

[27] T. Snyder, Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin, New York, Basic Books, 2010.

[28] ‘Andrzej Wróblewski 1927-1957’, Zachęta State Gallery of Art, Warsaw, 1995.

[29] J. Michalski (ed.), Andrzej Wróblewski nieznany, Kraków, Galeria Zderzak, 1993.

[30] Some sources refer to 30,000.

[31] A. Bubnys, ‘Eksterminacja Żydów wileńskich i dzieje getta wileńskiego 1941-1944’, Pamięć i Sprawiedliwość, no. 9/2 (16), 2010, pp. 229-272.

[32] The Lithuanian Riflemen’s Union, which provided the manpower for the collaborationist police formation Ypatingasis būrys.

[33] His primary employment was managing a succession of three camps: Neuengamme, Dachau, and Majdanek.

[34] K. Sakowicz, Dziennik 1941-1943, prefaced and edited by M. Wardzyńska, Warszawa, Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, 2014.

[35] J. Mackiewicz, ‘Ponary-Baza’, Orzeł Biały, no. 35 (170), 1945; reprinted in Nie trzeba głośno mówić, London, Wydawnictwo Kontra, 2012.

[36] Ibid.

Imprint

| Artist | Alina Szapocznikow, Andrzej Wróblewski, Andrzej Wajda |

| Exhibition | A Difficult Age. Szapocznikow – Wajda – Wróblewski |

| Place / venue | MO Museum, Vilnius, Lithuania |

| Dates | 20 March – 18 July 2021 |

| Curated by | Anda Rottenberg |

| Website | mo.lt |

| Index | Alina Szapocznikow Anda Rottenberg Andrzej Wajda Andrzej Wróblewski MO Museum |