As with every edition of Manifesta, the 14th “European Nomadic Biennial” is discussed in terms of its relevance, how it performs on a local level, as well as how many local institutions and artists it engages. This years’ edition, hosted in Kosovo’s capital Pristina, just in terms of numbers must seem like a success for all those who were critical – with 37% local artists and another 23% from the Western Balkans, as Manifesta counts them. I try to remain humble in judging this statistic since I don’t know the country well enough to develop my own perspective on it. After conversations there, I also feel it necessary to mention criticism about spending more on commissions from established artists from the region and investing less in the new generation of artists that live in Kosovo, as well as a lack of engagement with local cultural agents. Still, from an outside perspective, and despite a lack of support from the biennale, there were many initiatives from Kosovo that could be discovered. Judging by the relatively small size of the art scene, it is actually surprising to hear about the missed opportunities for engagement since any involvement would have also opened possibilities for younger generation artists and maybe engaging more different voices in the production of the biennale and, as the title implies, would have enabled the telling of stories, otherwise.

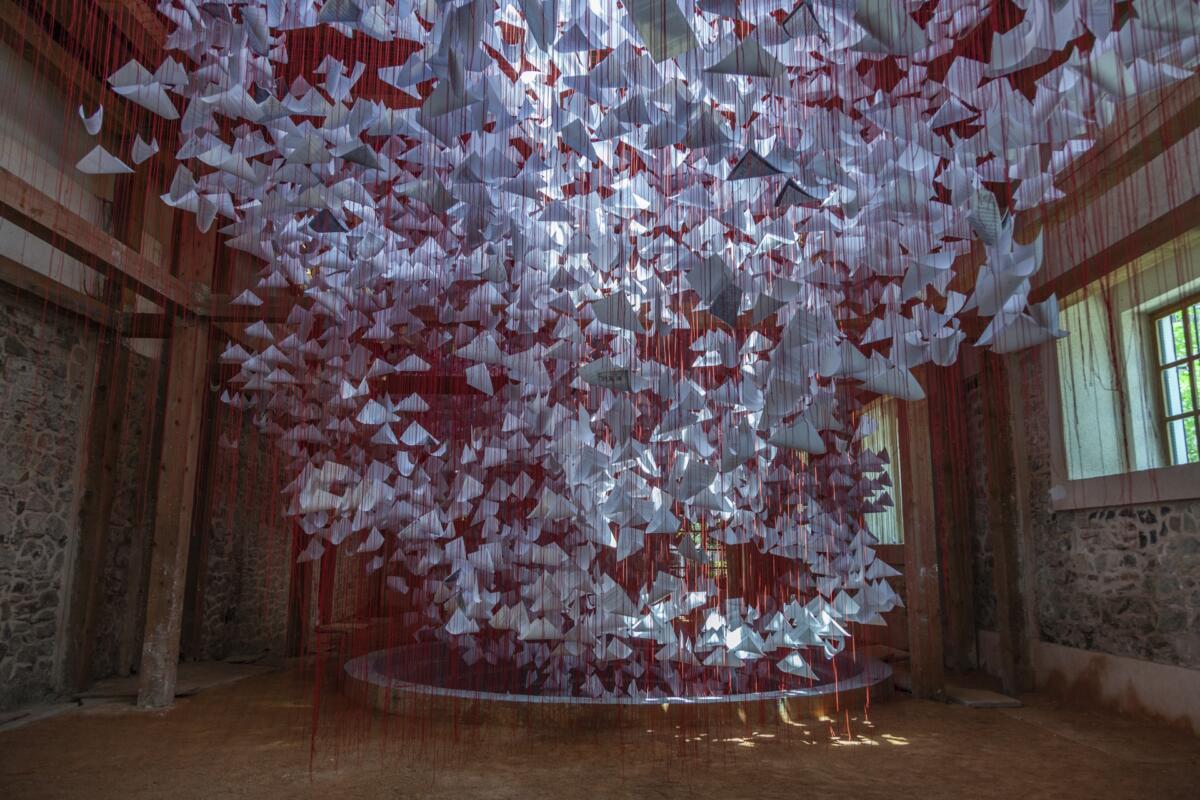

Having said all that, it shows that this is a biennale made for an international art audience, and most interestingly tries to act as an introduction to the art scene of the Western Balkans, without mentioning this as an explicit goal. The title and concept of the artistic program – It matters what worlds world worlds: how to tell stories otherwise – conceived by Manifesta 14 Creative Mediator Catherine Nichols, conjures a much larger discourse that cannot be narrowed down to such a local or regional question. The concept, which references Haraway’s idea of worlding rather than Heidegger’s human exceptionalism, tries to put storytelling in the center. With the exception of the artworks by Mette Sterre and Laureta Hajrullahu, who both offer stunning ways of thinking through materiality and media, the exhibitions remain fixed in narration from a human perspective – therefore emphasizing more the conflicts of the region and how they could serve as an alternative in thinking also in global politics. By bringing local and international artists together across venues, the exhibition bridges political and geographical contexts and narrates conflicting histories as a metaphor for other conflicts. This also sets the stage for the roles of love, ecology, or water – to name only a few of the sub-themes – and how they might inhabit these narratives, which is the most convincing part of the curatorial approach.

Among the most memorable works was that of Abi Shehu. Located in the Grand Hotel, the largest venue of Manifesta, Shehu’s work Sahara (2021) features wall engravings from the infamous Albanian prison Spaç, a labor camp for political dissidents during the Communist regime. Reviving them in a video sculpture made up of 15 old TV sets, Shehu thereby questions a dark part of the country’s history and its commemoration, in the exhibition. A more abstract way to deal with trauma conferred in images is seen in the presentation of Christian Nyampeta’s works – beautifully matched with the location of an unused cinema – which brings together different pieces– Sometimes It Was Beautiful (2018), A Long Trailer for a Film about Lovers in a Dangerous Spacetime (since 2021), and A Communion of Spirit (since 2016) – and goes through many layers of historical footage that have been blurred with conversations on postcolonial discourse, all the way to an imaginary meeting in which Swedish director Sven Nykvist, who shot a film about Congo in 1949, is confronted with the critique of the dehumanization of the subjects depicted through the violent gaze of othering. At the same time, one could say that a less metaphorical approach, such as Jelena Jureša’s Aphasia (act three) (2019) is more accessible. It takes its departure from the story narrated by journalist Barbara Matejčić, who identified a well-known Belgrade DJ, Srđan Golubović, one of “Arkan’s Tigers,” as the protagonist in an image of a man kicking the head of a dead Bosnian woman. By linking this narration with a choreography that makes one feel the connection between DJ Max’s music as well as to his violence, Jureša’s video truly conveys an emotional understanding of a complex context that is still relevant today.

While some works might also have connection with other topics and not only the subtheme that they’re part of, in every exhibition space one can sense that the curatorial approach was always to balance different artistic approaches and media, as well as different narrations and backgrounds. Mercedes Matrix (2019) by Selma Selman shows her and members of her family dismantling a Mercedes, a practice of making money by reselling valuable parts – that could easily be misread (and sometimes is described) as an act of violent destruction. The addition of Selman’s performance You Have No Idea (2022), therefore is a smart move. Performed several times for a “Western” context, it might have been read there as generally addressing the lack of understanding for the post-socialist background, but in Pristina the question of the other layers of identity that we might not be aware of comes to the foreground.

Even though many venues of Manifesta are repurposed, run-down buildings, as we’ve seen a lot over the past decades, the post-socialist context of the buildings in Kosovo for this kind of presentation actually adds another critical layer. Igor Zabel wrote in his text We and the Others (1998) that “a certain regional art phenomenon or idiom is first appropriated by Western interpretations, institutions, and capital, and subsequently ‘relocalized’ or ‘projected back’ into its original context.” With this in mind we can see that it is not the same post-industrial style of exhibitions from the 90s and 2000s, but rather another visual regime that produces a contradictory reading of this Manifesta. Namely, reinforcing the idea that this country reproduces its past over and over again, allowing only the artists who deal with that past to be included in the cycle of shows. While this paradigm luckily is not visible in the selection of artists’ works for Manifesta, it shows in the selection of venues: used as mere background for this type of post-industrial exhibition-making, embodying a kind of prejudice that traps many countries and their art scenes in a made-up image of some non-existent past.

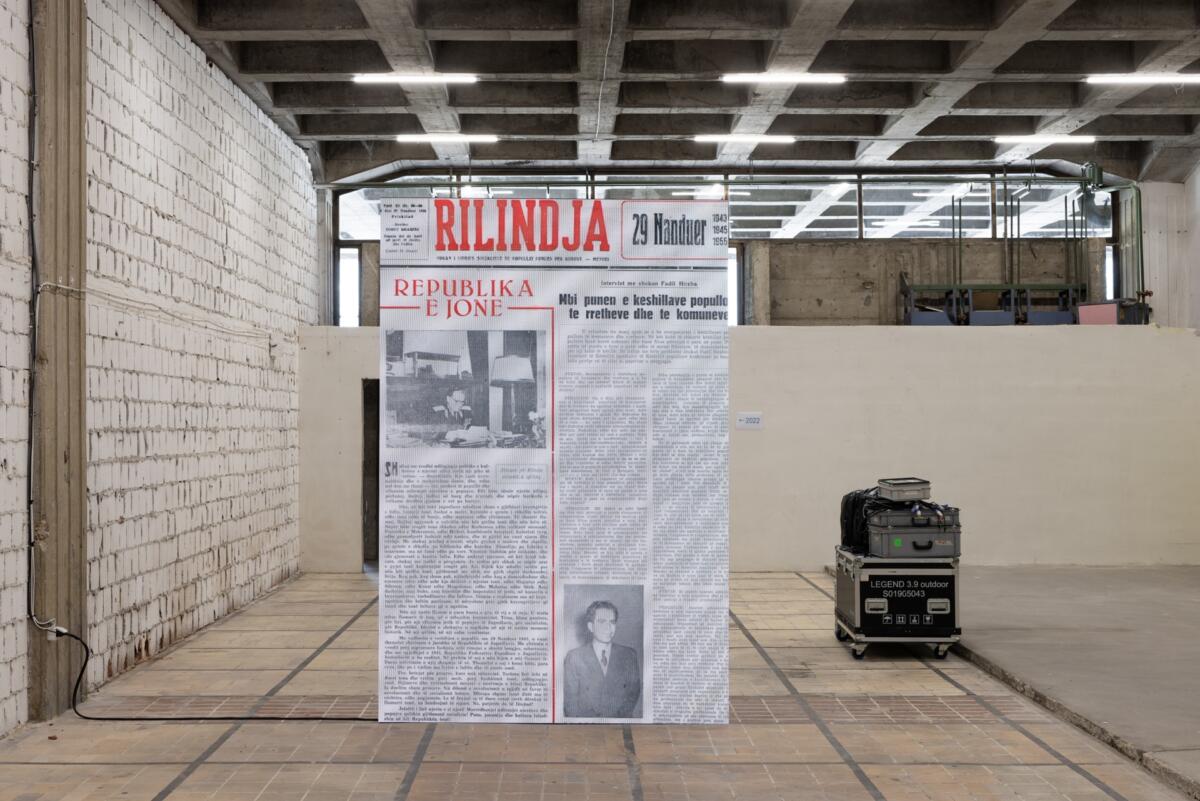

With this in mind, it is worth taking a look at parts of Astrit Ismaili’s performance LYNX (2022), featured in the opening event. The songs, written by Ismaili, deal with the ambiguity between attraction and decay within the same subjects and objects. While on the surface questions of gender stereotypes or self-destructive behaviour within queer communities are discussed, we could also translate this dialectic to the perception of, in this case, Kosovo – where local artists know the toxicity of making art based on their own unique, precarious stories to be desired by curators and audiences, and at the same time actually having the need to communicate their situations, which many people in the country also find themselves in. This, for example, also led to a huge number of reviews speaking extensively about the visa issues for Kosovars, demonstrating the benefits of an international biennale coming to this place, while at the same time revealing the symbolic acts that limit what this institution is actually able to do. The artwork Brutal Times (2022) by Cevdet Erek commissioned for the Rilindja building, the former newspress of Pristina, tells this story in maybe the most striking way, platforming the interweaving pasts of the building both as the headquarters of the newspaper with all its influential front pages and of the techno parties that happened there after the newspaper was shut down. In the space, a large screen shows the past front pages of Rilindja, and we only hear the distant echo of techno beats and the keystrokes of a typewriter from the inaccessible basement where we can also spot some lights, too. Despite the beautiful connection of the sounds of these two pasts, neither the work nor the curatorial decision of using this space open up something more than the very different pasts of this building. Even a new party recently held in that space in the framework of Manifesta’s program just invokes the past spirit of its alternative use for electronic music events but doesn’t create a vision for its further use.

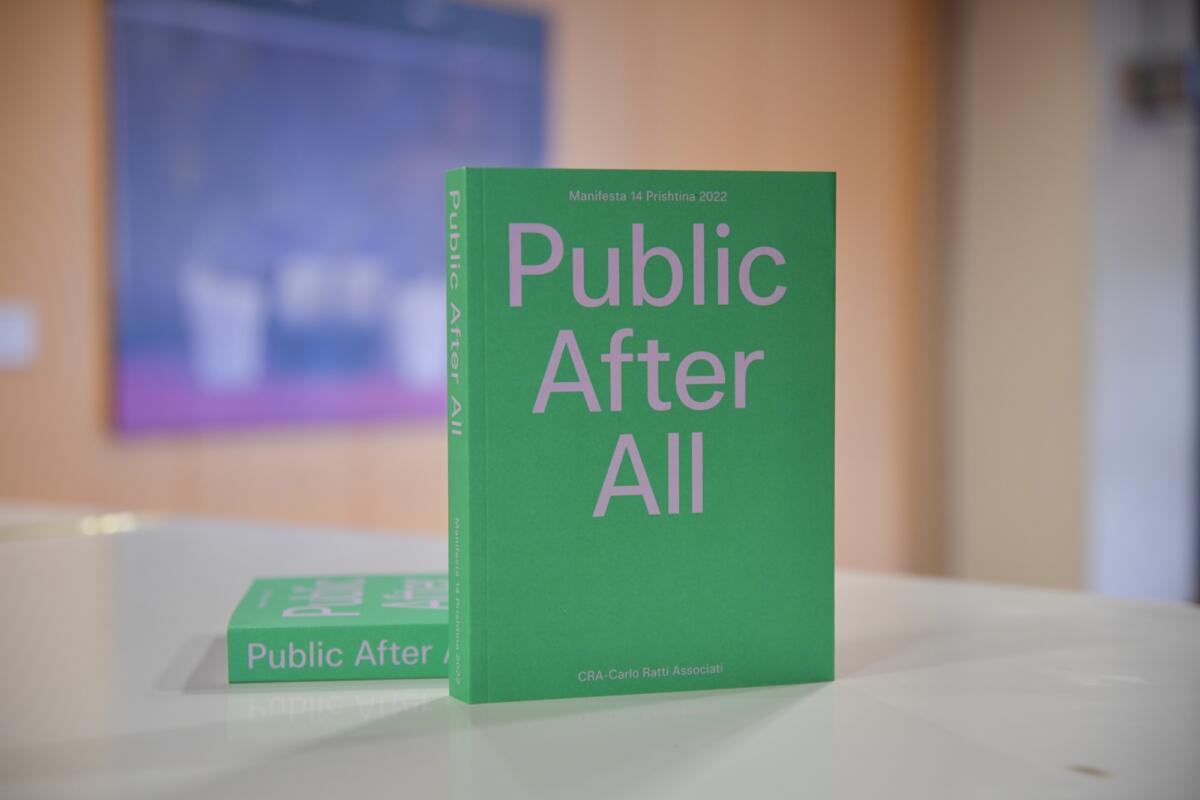

Manifesta 14 did manage to implement one project with a foreseeably lasting effect; the renovation of the Hivzi Sulejmani Library, which became the Center for Narrative Practice for the biennale and continuing forward, will remain a cultural center for future use. Despite this example, overall, the beautifully conceived exhibitions of Manifesta turn into symbolic acts that don’t try to actually tackle the problems of the local art scene or of the local people. While it is good to create potential, it seems hypocritical when it is done by an institution that is criticized for this exact move in every edition. And despite the “urban vision” realized by Carlo Ratti Associati, dealing with the right topics and sites within the city, I got the feeling that the interventions with yellow wooden architecture to create public spaces could have been more powerful if they would have surpassed this style of temporary DIY interventions.

While the artists and programming tackle many different narratives, as a whole, this edition of Manifesta seems to boil down to a conversation between the works by Flaka Haliti and Petrit Halilaj. Haliti’s Under the Sun – Explain What Happened (2022), placed on a part of the Palace of Youth and Sports complex, is a stand-in for a sunrise or sunset, or maybe just a fire behind a camouflage-like structure. Halilaj’s When the sun goes away we paint the sky (2022), with the eponymous line and stars, echoes the old signage on top of the Grand Hotel. They could stand for the two poles of the country, of history and utopia, and speak about their need to be addressed in new ways. But while providing an alternative is something these artworks seem to be able to do, the heavy context of the biennale brings them back to stand-ins for these simple, hackneyed oppositions and offers a solution to neither of them.

Edited by Ewa Borysiewicz and Katie Zazenski

Imprint

| Exhibition | Manifesta: European Nomadic Biennial |

| Place / venue | Pristina, Kosovo |

| Dates | 22.07-30.10.2022 |

| Index | manifesta Maximilian Lehner |