Martyna Nowicka: Why, in a small city on the Danube, do we find a riverbank park

full of steel abstract sculptures?

Annamaria Nagy: Those sculptures have close ties with both the history of this place and the biennale which used to be held here over almost thirty years. At first, their presence may seem surprising, especially if we enter the park having walked through the socialist realist part of Dunaújváros, but in fact their origin can be traced back to the very same socialist guidelines as in the case of this entire city.

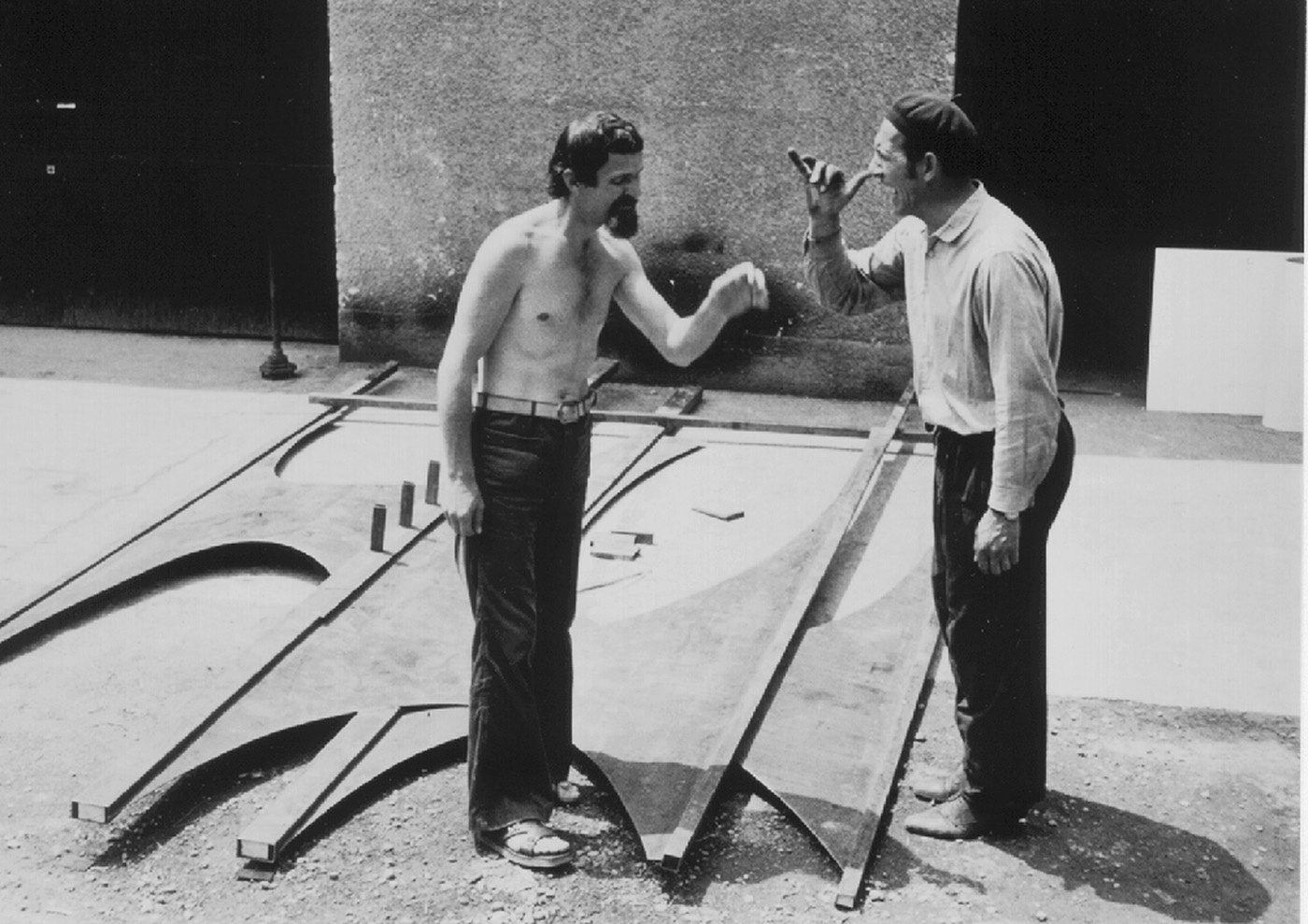

Dunaújváros sculpture biennal, 1975

Everything here started with the idea that Hungary needed a steelworks. Before the Second World War it was predominantly a rural country: it had favourable climate and fertile soils, so crops had been good here for ages. After 1945, however, a decision was made to turn the People’s Republic of Hungary into a coal and steel tycoon. Trouble was we barely had any deposits of those resources. According to the original vision, the steelworks itself and the perfect city surrounding it, the capital of metallurgy, were supposed to be located much closer to the Yugoslavian border. Due to strategic reasons, they were eventually established here, right in the middle of the country. Resources were meant to be transported over from the mountains down the Danube, but that idea soon proved rather dubious. The water level in the river was almost always either too high or to low, and the current too brisk or too slow. All in all, the plans only looked good on paper.

There were attempts to encourage artists to move to Dunaújváros. Painters and sculptors would be given flats and workshops here apart from being offered regular salaries. In return they created for the city and were obligated to engage in community life, e.g. through running art clubs.

Not all of Dunaújváros looks socialist realist. There are more locations which, like the sculpture park, come from a different aesthetic reality.

That is true. The first architect who took charge of urban planning and construction around here was Tibor Weiner. He had been trained in the Bauhaus, worked in the USSR, in Basel, and in Paris; spent the war years in Chile, and only came back lured by a chance to build a new city from scratch. The first designs here were truly modernist, but the communist party soon gave up on those aesthetics. Modernism was not compatible with Stalin’s idea of a city. What they did not give up on was their approach towards the people who would live here. From the very beginning it was a wealthy place: a model for all the other socialist towns and cities. Even though it was originally meant to only have 20 thousand inhabitants, those people were given not just hospitals and canteens, but also cultural community centres, a cinema and a theatre. Next to the plant, a city began to grow: one that was supposed to be a model, and whose inhabitants would live perfect socialist lives.

Dunaújváros sculpture biennal, 1975

Does that mean culture was always meant to be important here? Which artistic discipline was most emphasised?

From the start, the authorities focused on high culture. That was why not only works of art were brought over and cultural infrastructure was built, but there were also attempts

to encourage artists to move to Dunaújváros. Painters and sculptors would be given flats and workshops here apart from being offered regular salaries. In return they created for the city and were obligated to engage in community life, e.g. through running art clubs.

The plant was also engaged in cultural life, for example, via its scholarship system that anyone who wanted to study could benefit from. And by ”studying” I do not just mean studying engineering: the program applied to artists and humanists too.

Where would such clubs operate? At the community centres?

No! In most cases in neighbourhood after-school rooms, in the very blocks of flats. Those were not top-down ordered obligatory classes, but an opportunity to talk about art and specific works, also the things particular artists were working on at that moment. The artists would come here for something similar to a residency, but their stay would last their whole life.

Still, at the very heart of the city was the steelworks, not art.

Of course, but that does not alter the fact that the plant was also engaged in cultural life, for example, via its scholarship system that anyone who wanted to study could benefit from. And by ”studying” I do not just mean studying engineering: the program applied to artists and humanists too. Also the origin story of the sculpture park is, just like almost anything in Dunaújváros, connected to the steelworks. Istvan Birkas, artist and engineer who used to work at the plant, came up with an idea to take advantage of the city’s great technological assets and invite sculptors over for a workshop. The first workshop took place in 1974. It was then held at the local collage, but the supplies obviously came from the steelworks. A year later, in 1975, the invited artists would move to the very plant, where regular workers would help them in working the metal. That year a decision was made to make the event cyclic. By the way, the very idea was born in Elbląg [Poland] where the local plant organised the Biennale of Spatial Forms. Its last edition took place one year before the first workshop in Hungary.

Dunaújváros sculpture biennial, 1975

What were those workshops like? Who could apply for a stay in this model socialist city?

In the first years of the biennale, it would be attended by committee-selected artists.

As of 1977 you could submit your project, and the jury consisting of members of the Young Artists Association would choose the most interesting designs. Since 1983 the event has had international character, so today we also have works of Scottish or American sculptors in Dunaújváros. Every two years, selected artists would come and spend several weeks here. They were given per diems, accommodation and boarding, just like artistic residents. All those who were accepted could use the material provided by the steelworks, in which they worked during their stay. Every participant was also assigned their own crew. Sometimes, there were funny situations, since those crews, as was customary in socialist countries, were named after Lenin, Stalin, Gagarin, etc. One crew, having worked with György Galántai, applied for their name to be changed in his honour.

Was their request granted?

Regrettably, no. Galántai, founder of the Budapest Artpool research centre, was frowned upon. In Hungary, artists were divided into three categories: those who were generously subsidised by the state, those who were not, and those were even deprived of chances to exhibit their work. He was a member of the latter group, and therefore could not apply for any scholarships or donations. Still, he was able to come here six times, which is more than anyone else.

How did that happen?

It is like in the proverb: you can’t see the wood for the trees. And so, here, in this model city, a little more then elsewhere could be tolerated. On the other hand, let us not fool ourselves: we are still in the peripheries, not in Budapest. It now takes an hour to get here, but back then the trip was much longer and less comfortable. Also, the artists’ works would stay in Dunaújváros, so the Young Artists Association could pick them based on quality, not policy.

Dunaújváros sculpture biennial, 1975

It seems being in the peripheries was good for everybody.

The steelworks was, of course, state-owned, but certain rules could be omitted. It was

a niche where not all the regulations were strictly enforced. Actually, it stayed that way for long, and even after 1989 little changed. Up until the year 2000, when the steelworks was privatised and sold to a Ukrainian company, the scholarship system and the biennale were kept alive. That way, it was possible to maintain the event until the end of the 1990’s. In that decade it was only held in 1993, 1996 and 2000, but at least it survived the political shift. Once the steelworks got privatised, municipal funding was also withdrawn.

Not all the inhabitants know the story and why the sculptures are even here. But even so, the park is very present in the local collective consciousness: teenagers like to come here, they party and take pictures.

Were the biennale sculptures always created with the Sculpture Park in mind?

Not in the least! It is one of many things which happened by chance. The objects created during the workshops were stored in a warehouse. Once, when some high-rank official visited Dunaújváros, they were displayed on the river bank just so the city could boast of them. And there they are (albeit arranged differently) still today.

Dunaújváros sculpture biennial, 1975

Back then, it had already been three decades since the times of Tibor Weiner and his modernist ambitions. Did the locals like the abstract steel sculptures?

No, not at all. Both the city dwellers and the local politicians were very sceptical at first. They were used to socialist realism designs, and did not care much for avant-garde. On the other hand: many of them worked for the steelworks, some had even been directly involved in the production of the works. The latter were enthusiastic from the very beginning, because they saw the sculptures as something to be proud of. Today, views are divided. Some do not like the sculptures, because they would like socialism as such to be wiped out from the city’s history, as if they really did not understand that was not feasible. Not all the inhabitants know the story and why the sculptures are even here. But even so, the park is very present in the local collective consciousness: teenagers like to come here, they party and take pictures. The most characteristic sculptures even have their nicknames, sometimes several, each used by a different generation.

Still, we cannot not notice that the sculptures do not look like new anymore. In places, there is rust. They could use a renovation.

That is why at the Dunaferr-Art foundation we are trying to renew both the sculptures themselves and the tradition of the event. The first thing should be achieved next year: we’ve been applying for funds for some time now, but since the sculptures are supervised

by the Ministry of Human Capacities the procedures have taken a few years to commence. Another thing is the biennale. Already in mid-November, after a fifteen-year interval, another edition will be held in Dunaújváros. This time the scale will be more modest, but still we managed to secure funding and invite three young artists to collaborate. They are Péter Szalay, Kitti Gosztola and Tamás Kaszás. Once again, the Young Artists Association helped with the selection. We’ve also been able to once again convince the steelworks to take part. The times of free-of-charge steel may be over, but we are still thrilled that history will come full circle.