What if things could speak? What would they tell us? Or are they speaking already and we just don’t hear them? And who is going to translate them?[1]

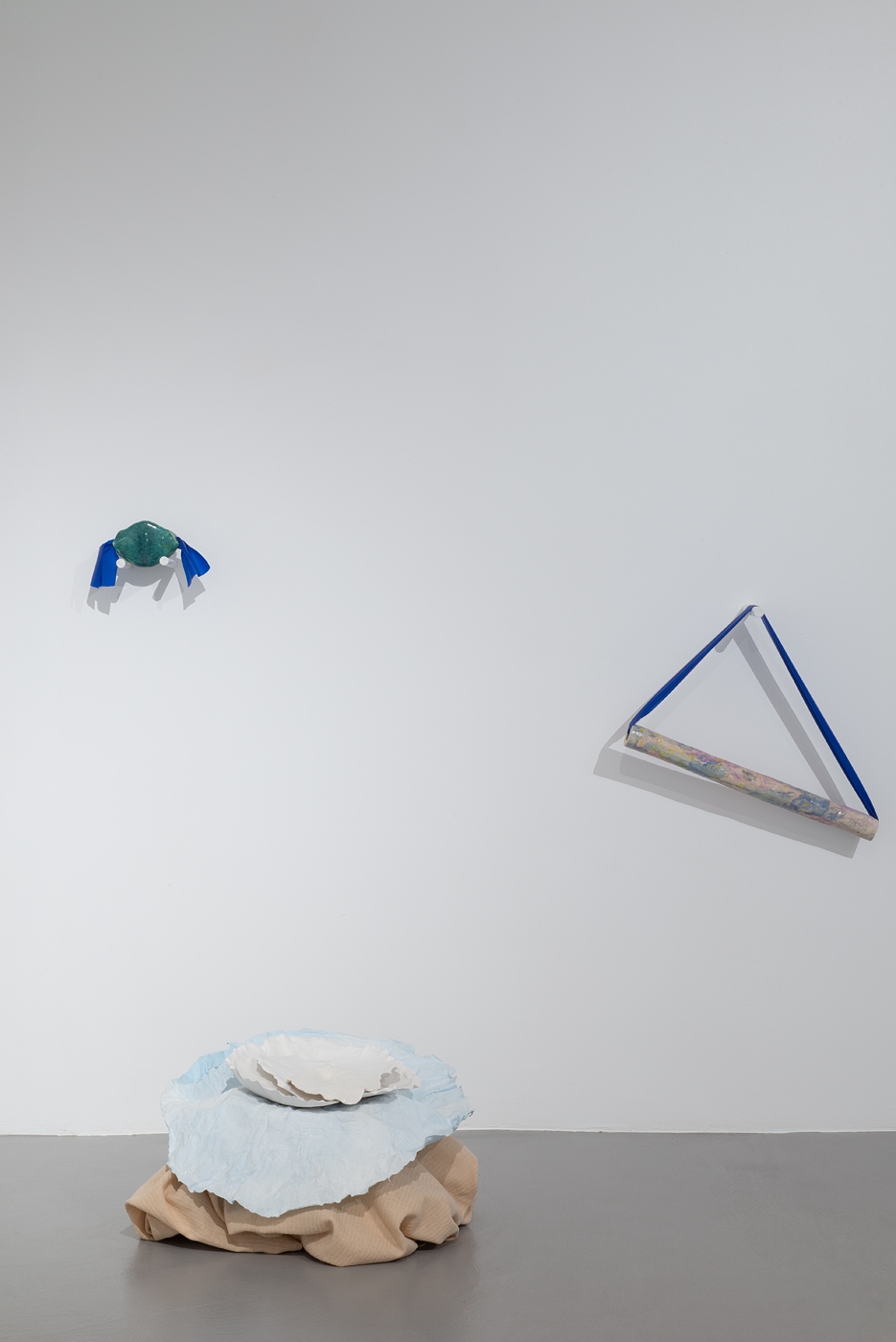

In the broadest sense, this exhibition looks at the material culture and the stories, meanings, and transformations that lie in it. There has been a long tradition in society to admire objects of tangible culture from the past, but how do we connect with objects in ourcontemporary society that surround us daily? This exhibition explores the social stories, hopes, and desires that have settled in the matter around us. Artists are like anthropologists who study the different meanings of things through form, materials, usage functions and socio-cultural histories.

What kind of expectations, and meanings tie us with things around? And how does one influence his own perceptions, understandings, and habits through the material things he constantly creates around him? In our daily lives, things play an important role in both material and immaterial ways. We fetish their utilitarian or aesthetic qualities, but rarely think about their possible additional meanings and hidden potentials. “Chatty Matter” is based on a visual and tactical research on things that have lost their function, or which function is unknown or yet undiscovered. What purposes, meanings, and ways of being manifest in things that surround us every day, when we remove the ideological meanings and utility functions that are attributed to them by humans? Furthermore, what (social) agency could these things possess in addition to their exchange value?

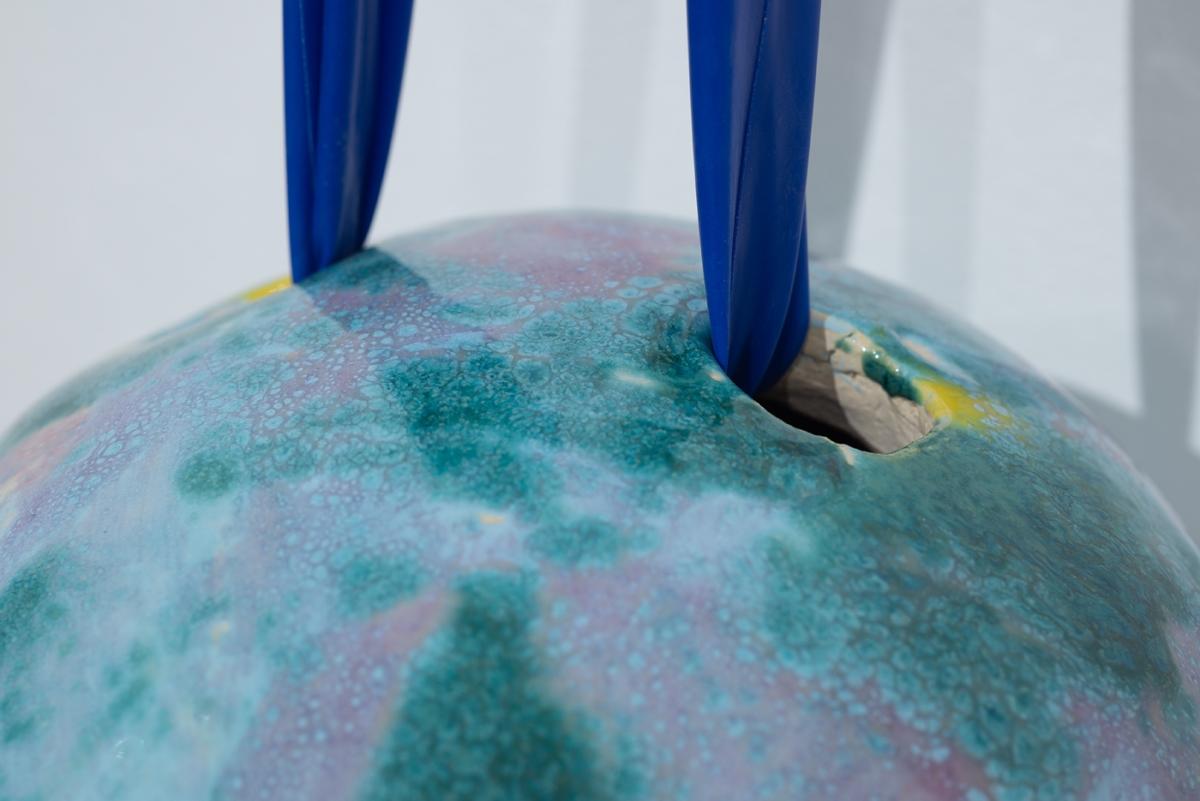

Artists are fascinated by situations where objects have lost their purpose or commute between function and aesthetics. Through the study of decorative semi-functional things, Saarits investigates objects in which the social desirability of success and dreams of consumerism have materialized. By observing the origin stories of different things, she alsoanalyses the topic of “thingliness” and the ontological meanings of things in a wider context. Mertes however, combines special types of materials and parts of commodities and is engaged in rethinking the perceptions and everyday habits related to things around us. Emphasizing on the material presence of the work of art and the desire to remove the semantic baggage of different objects and materials, she thus opens up their new possible meanings and uses.

The art practices of Saarits and Mertes are framed by a new materialistic thought, according to which matter and things have a certain self-sufficiency, agency, and hidden potentials. In this sense matter is an autonomous entity: it is the man who attributes it to different meanings and uses. At the beginning of the 21st century, one of the main socio-cultural causes for the development of the new materialist philosophy was the dematerialization of art, economy and bureaucracy that began in the West. Starting from the center of the social model which mass-produces images, and which operates primarily on digital technologies; where more personal and direct experience with objects and materials was increasingly disappearing, it came to an understanding of the autonomy of objects and the material world. This philosophical way of thinking derives from a speculative realism and, more specifically, from object-oriented ontology, and is based on a belief that objects around us are independent of human perception. In the practice of contemporary artists, it primarily took the form of thorough and conceptual object and material studies. Through the direct study of everyday objects and materials, their histories and context of their creation were deciphered, while there was also a clear ambition to rethink the meanings and values associated with a particular object or material.

Saarits and Mertes likewise draw attention to the material presence of the work of art, while they are interested in the ontological meaning of things and materials. Working often according to the material, artists are interested in new interpretations of material culture. In the context of this exhibition, however, there has been added an exploration of the topic of things and thingness[2] as such. According to thing theory, if a thing loses its usual function, e.g. it breaks or is misused, it loses its socially encoded value and appears to us in new ways. Bill Brown, the founder of the thing theory, is convinced that we begin to confront the thingness of objects when they stop working for us: when the drill breaks, when the car stalls, when the windows get filthy; when their flow within the circuits of production and distribution, consumption and exhibition, has been arrested, however momentarily.[3]

By placing things in unusual roles, shifting our usual ways of thinking and acting, and deconstructing the meanings and exchange values attributed to things by man, Saarits and Mertes also hope to highlight the potentials and the yet undiscovered values of everyday objects. By studying things, artists are able to interpret more broadly the reality surrounding us: the objects of everyday life as the material reflection of the human world can tell us something new about the transformations taking place in the society.

Walter Benjamin has created a theory of the language of things (in “On Language as Such and on the Language of Man”, 1916), further developed by Hito Steyerl in her text “Language of Things” (2006). For Benjamin, the language of things is productive, full of potential and forces; it is mute, it is magical and its medium is material community. Thus, we have to assume that there is a language of stones, pans and cardboard boxes. Lamps speak as if inhabited by spirits. Mountains and foxes are involved in discourse. High-rise buildings chat with each other, Steyerl insists cleverly.[4] The respective form of translation (between humans and things) will decide, if and how the language of things with its inherent forces and energies and its productive powers is subjected to the power/knowledge schemes of human forms of government or not. It decides, whether human language creates ruling subjects and subordinate objects or whether it engages with the energies of the material world. To start listening to them again would be the first step towards a coming common language, which would not be rooted in the hypocrite presumption of a unity of humankind, but in a much more general material community.[5] Perhaps it is the artist’s role to actualize what the surrounding matter wants to tell us – to decode the language of things – which, in turn, can become productive especially in the transformation of social power relations.

[1] H. Steyerl, The Language of Things. – EIPCP.net. June, 2006.

[2] According to Martin Heidegger: quality of being a thing; also related to thingness (das Dingsein).

[3] B. Brown, Thing Theory. – Critical Inquiry, Vol. 28, No. 1, Things. (Autumn, 2001), pp 4.

[4] H. Steyerl, The Language of Things. – EIPCP.net. June, 2006.

[5] H. Steyerl, The Language of Things. – EIPCP.net. June, 2006.

Imprint

| Artist | Kati Saarits, Nora Mertes |

| Exhibition | Chatty Matter |

| Place / venue | Kogo gallery, Tartu |

| Dates | 09 February–23 March 2019 |

| Curated by | Brigita Reinert |

| Website | www.kogogallery.ee/en/ |

| Index | Brigita Reinert Kati Saarits Nora Mertes |