Make it to Spring

What are our ancestors to be hailed for? Our, namely, the Poles’. And I certainly do not have in mind those who scuttled from insurrection to insurrection, fighting for an independent existence of “the nation”. For their goal, indeed, was an independent functioning of their mansions, and the very nation was restricted to residents of those mansions. I mean a decision taken around the 6th-7th century of the common era by the moustachioed proto-Januszes[1], when they drove their spears into the ground and made up their minds to stay here. They could have moved on. Where the other Slavs – Serbs or Croats – went, for example. Those slackened no pace and concluded that if they were going, they were going – all the way, in the direction of the Mediterranean. They did not really manage to get there, but their very idea deserves respect. I have no idea what motivated the latter hordes, but at least with respect to the climate, they made a better choice.

The proto-Januszes stayed here. And since then the defining feature of our fate, thinking and behaviour is winter crop. Yes, indeed, precisely. In a region where temperature ranges from minus 30 degree Celsius during winter to plus 35 in summer, life is hard to get used to. A hundred years ago, when transition periods from winter to summer were longer, and when early spring had not year become The Coming Spring, an assigned school reading, it might have been slightly easier. However it might have been, the basic problem remains the passage from the extreme heat of summer to the extreme cold of a few months later. Leaving aside the fact that the very ‘housing infrastructure’ they occupied – dugouts shared with goats, rams and hens – ought to have encouraged our forefathers to flee as far south as they could. Where the climate is gentler, the transitions between seasons – not as violent, temperatures in winter are bearable, and the summer air – less humid. Whether the supposed Slavic sloth, or a plain weakness, it nonetheless made them stay here and decide to be getting used to it. No to get, but be getting used to. Twice a year, routinely, for several hundreds of years. First, the mental and biological thawing after winter, the wait for sunrays and the curious leaping up from the dugout to feel if it was any warmer. And after a few months, the slow freezing, closing in, going into survival mode, endosporous. Neither this, nor that. Neither cold, nor warm. In a constant state of transition. It surprises no-one that the Romantic prophet, Mickiewicz, said the nation is like lava, cold and hideous stuff, and crusted, on the outside, crackling only within. Time and again, it sprouts, but for no more than a brief while, only to follow the call to retreat within bounds.

As much as we wear the badge of big-city young talents. Everyone readily forgets – of which we were reminded a few years ago by Andrzej Leder in his Dreamt-through Revolution – that around three fourths of contemporary Poles hail from the countryside, country men and women all. But it was precisely there, in the countryside, that the forms of custom and rituals in line with natural cycles have survived the longest. There, nature, climate, weather conditions were most painfully felt and determined, still determine rhythms of labour and celebration. Our big-cityness, our worldliness are still, in fact, nothing but aspirations, as no more than two or three generations ago our forebear jumped out of his thatched hut into the frozen snow to relief himself or took off his papakha before his master. Being aspirations, they are as parochial as our un-worked-through origins. And together with the origins we so carefully hide from ourselves, we must be carrying the survival, endosporous mentality as well. In line with the change of seasons, it made us either open, or close up, but never for good, due to our firm conviction that things would soon be different.

Ostensibly, waves of peasant-mania are threaded through indigenous arts and culture. The Young Poland took up the thread of the peasant, fronting a focus on folklore and taking marriages with country girls as fraternising with the people; the People’s Republic propaganda, in spite of its declared adoration for the country, bequeathed nothing but “Cepelia” – the Central of Folk and Artistic Industry; and even the activities of the Lucim Group[2] – unique and deserving of in-depth analyses – also celebrated, rather than assimilated, the countryside; while the rural theme, recently ‘discovered’ by curators in young Polish visual arts, was handled superficially at best, if not folkloristically. No-one wanted to delve into the character of the peasant, deeply rooted in the Pole. The character which makes us so similar to the winter crop.

The obviously tongue-in-cheek outlined metaphor of – a changeable and extreme temperature which affects people’s perception of reality – does, indeed, have quite serious connotations. The Polish visual arts have overlooked them completely. Another chance to take a closer look at them is the vogue, spreading from Sankt Petersburg through Minsk and Warsaw to Prague, for the Slavic. And although it may seem that its oversaturation with post-Soviet themes is a mere expression of a historic nostalgia or, at any rate, the cyclically recurring popularity of retro-styles of previous decades, it can produce interesting effects in at least two dimensions. First, employing (post)Soviet motifs, a generation born in the 1990s does not only nostalgically draw on childhood memories. Confronting the brutality and uncouthness of appearance of the then working class, the small town and village residents, with the current Western standards, they raise questions concerning not only whether and at what cost the economic transformation has succeeded in the Eastern Bloc. They also demand that we consider effects of rampant industrialisation of the areas east of the Elbe. Reasons why the ‘civilisational leap’, extending throughout several generations, has been so superficial and why the upward social movement of vast swathes of population migrating from the countryside to industrial centres has been so fragile. Second, expressly affirming their own past and the previously marginalised (as unbefitting Western aspirations) motifs, they penetrate identity and asks questions about relationships between this region of Europe and its Western section.

Then, perhaps, the metaphor of the winter crop, however too roughly hewn and raunchy to be true, might not be entirely missing the point? Perhaps, the endosporousness is a rather elegant way to describe us – the Slavs, the Poles, the locals? Constantly in-between the East and the West, neither colonies, nor empires, neither industrialised, nor underdeveloped. Neither cold, nor hot. That is one aspect of the winter crop. Another is its immediate consequence. It has been brilliantly captured by Ziemowit Szczerek, who often underscores the ‘endosporous’ elements of Polish identity in his texts. Primarily, the constant shifting of responsibility for the fate of the country onto others, larger ones, who are restrictive or insufficiently supportive – just like the overlord who molested the peasant with serfdom. Besides, a lack of care and attention to the public sphere, including a propensity for makeshift solutions and provisionality in architecture. If the master owns it, let him care. What matters is to rig things up. What matters is to survive. To make it to spring.

Text: Łukasz Białkowski

[1] Janusz – a derogatory term for a ‘civilisationally rearward’ Pole. used by other Poles; originally, a male name.

[2] Cf. http://cejsh.icm.edu.pl/cejsh/element/bwmeta1.element.desklight-41e3fc6f-0556-42de-802b-584c8064ae6f

Imprint

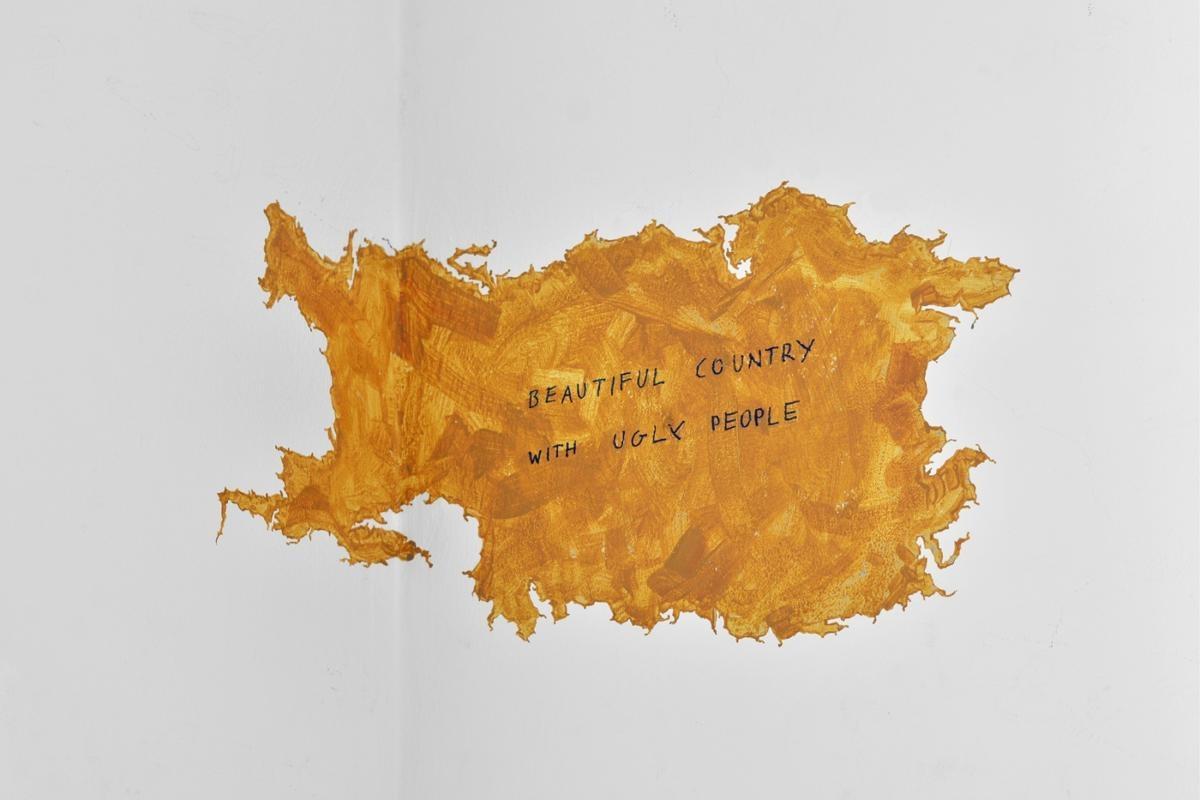

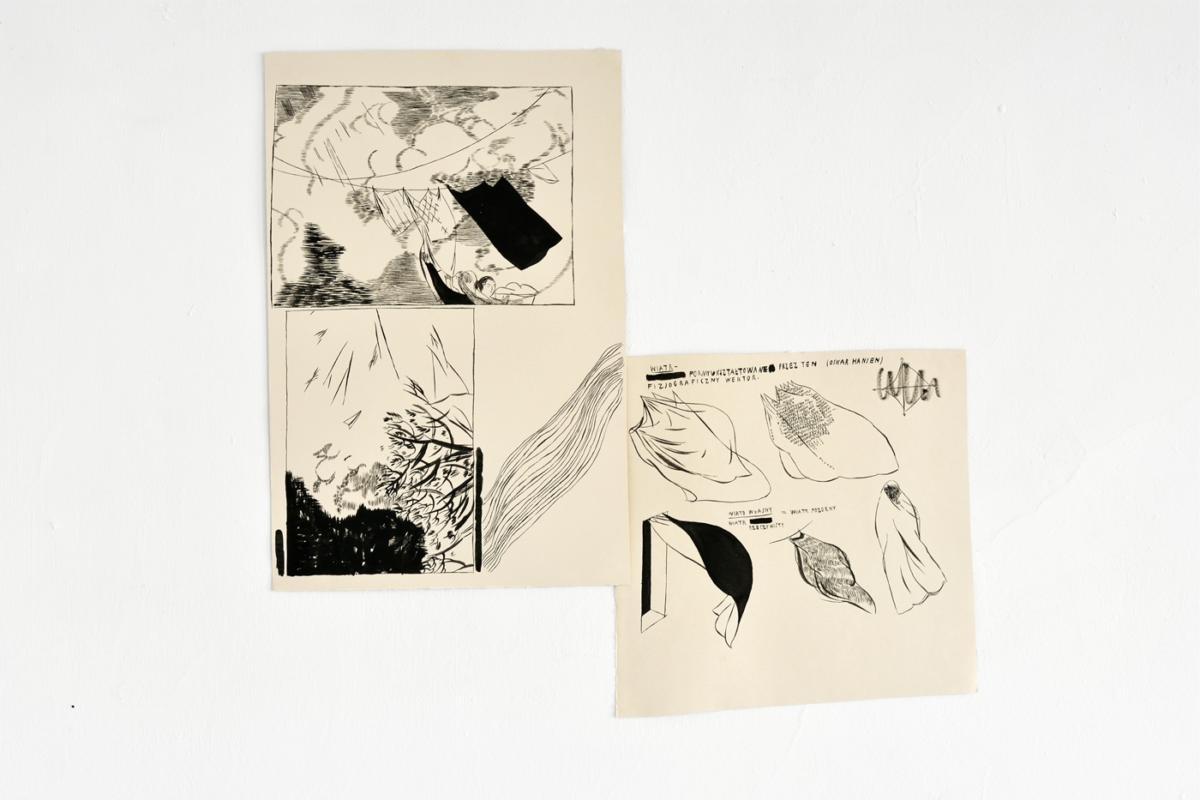

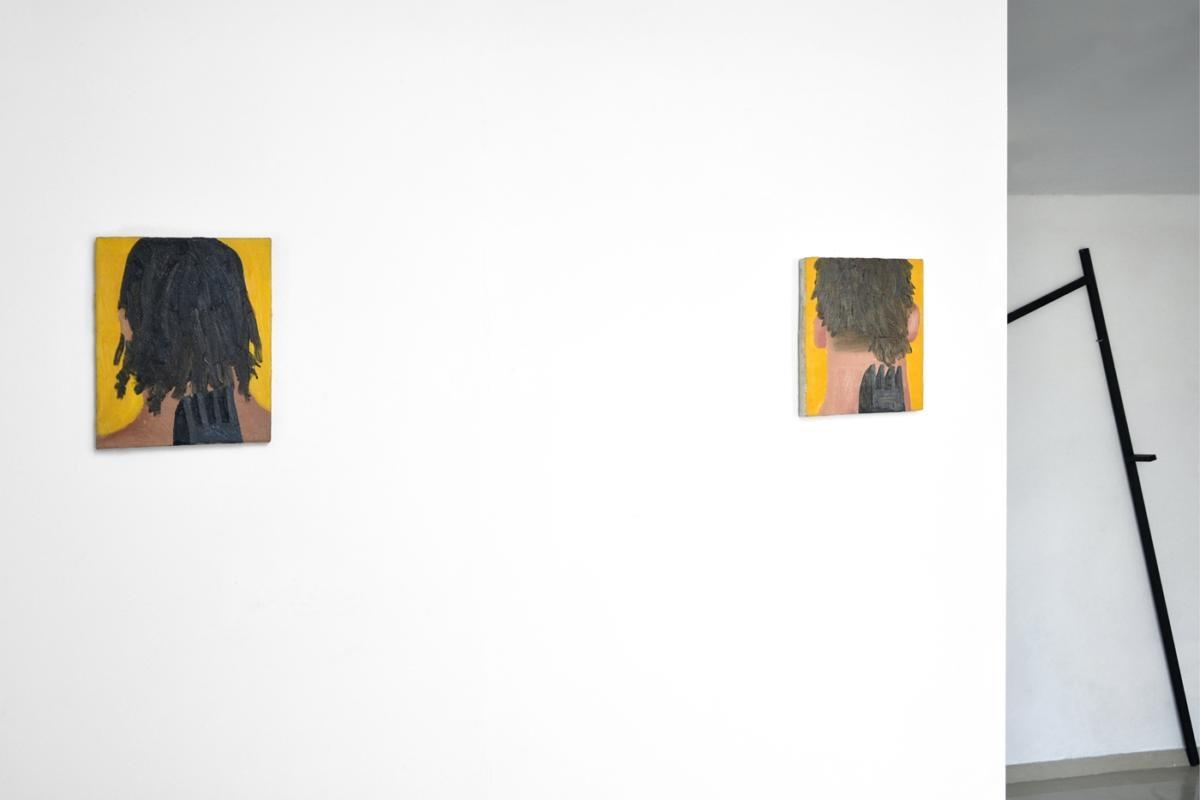

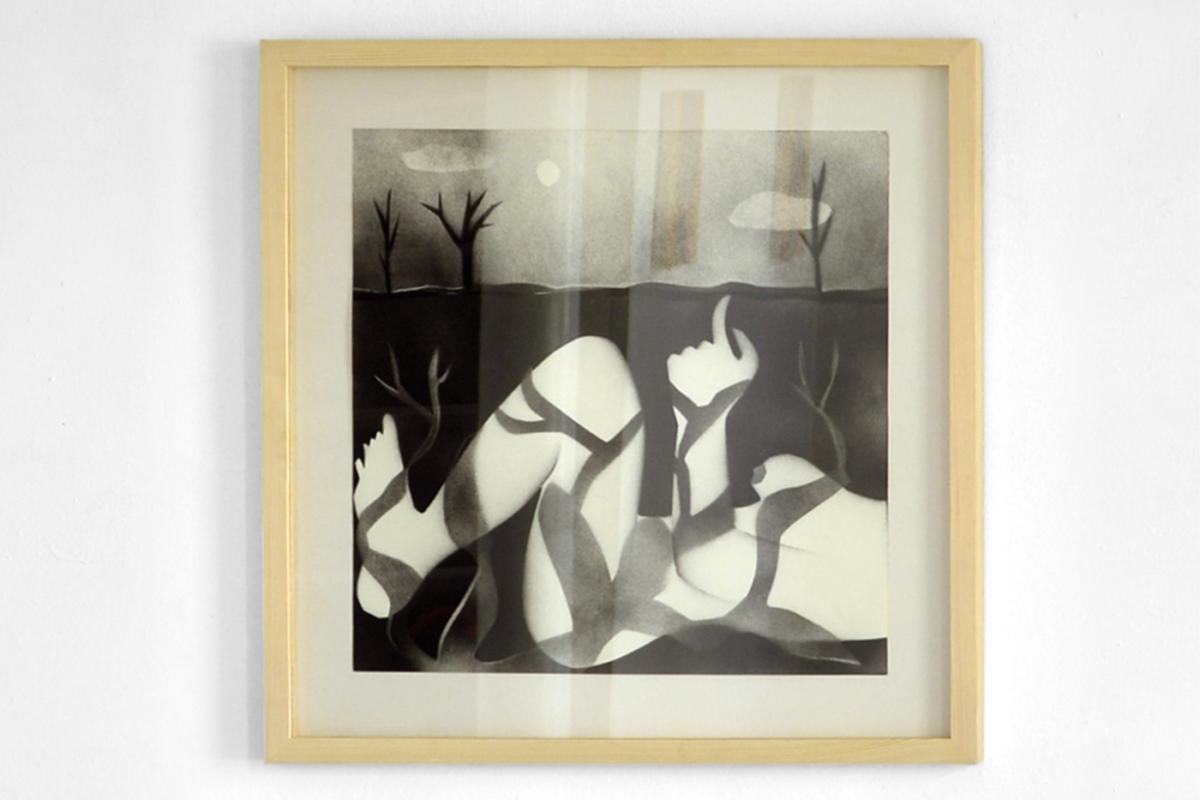

| Artist | Karolina Jabłońska, Kornel Janczy, Tomasz Kręcicki, Krzysztof Maniak, Agnieszka Piksa, Cyryl Polaczek, Magdalena Sawicka, Marianna Serocka, Ludmiła Woźniczko, Michał Bratko |

| Exhibition | Winter Crop |

| Place / venue | Widna Gallery, Cracow |

| Dates | 24 March – 17 April 2018 |

| Curated by | Agnieszka Piksa, Michał Bratko |

| Website | widna.pl |

| Index | Agnieszka Piksa Cyryl Polaczek Karolina Jabłońska Kornel Janczy Krzysztof Maniak Ludmiła Woźniczko Łukasz Białkowski Magdalena Sawicka Marianna Serocka Michał Bratko Tomasz Kręcicki |