‘Welcome to the Country Where the Gypsy’s Been Hunted’ by Krzysztof Gil at Henryk Gallery

Anti-Roma legislation as well as specific legal acts directed against the non-sedentary Roma population, justifying and legalizing the previously customary aversion towards the people and their prosecution, started to be drawn up and enacted in Western Europe in the early Modern era. Adam Bartosz in his book, Nie bój się Cygana. Na dara Romestar [Do Not Fear the Gypsy], lists only a few of these. According to the scholar and expert on Roma history, the first anti-Gypsy and anti-Egyptian – as they were known at the time – laws were issued in Lucerne in 1471 and barred the Roma from presence on the territory of Switzerland. At the close of the 15th century, the Roma were forbidden to follow their itinerant life style on pain of corporeal punishment and enslavement. In turn, the early 16th century was marked by anti-Roma legislation of the Habsburg Holy Roman Emperor, Maximilian I, in the light of which the Roma captured on the imperial territory were subject to torture and extermination. In 1530, they were legally banished from England, and ten years later – from Scotland. Expulsion acts kept been issued in the 16th century, among other countries, in Denmark, Finland and France.

Persecution of the Roma in the light and majesty of the law reached its apogee in the following – the 17th and the 18th – centuries. These, indeed, were the times when German lands and the Dutch Republic were home to the so-called Heidenjachten, the Gypsy hunts. The hunts for the Roma travelling to their misfortune through areas under the prohibition of their presence, or hiding from prosecution, assumed the shape of a battue, a non-infrequent source of pleasure to their hunters. A proof of evidence quoted by Adam Bartosz is an excerpt from a 17th-century German chronicle, containing the following report of one such hunt: “one beautiful stag was slain, five does, three sizeable wild boars, nine smaller boars, two male gypsies, one female and one baby gypsy.”

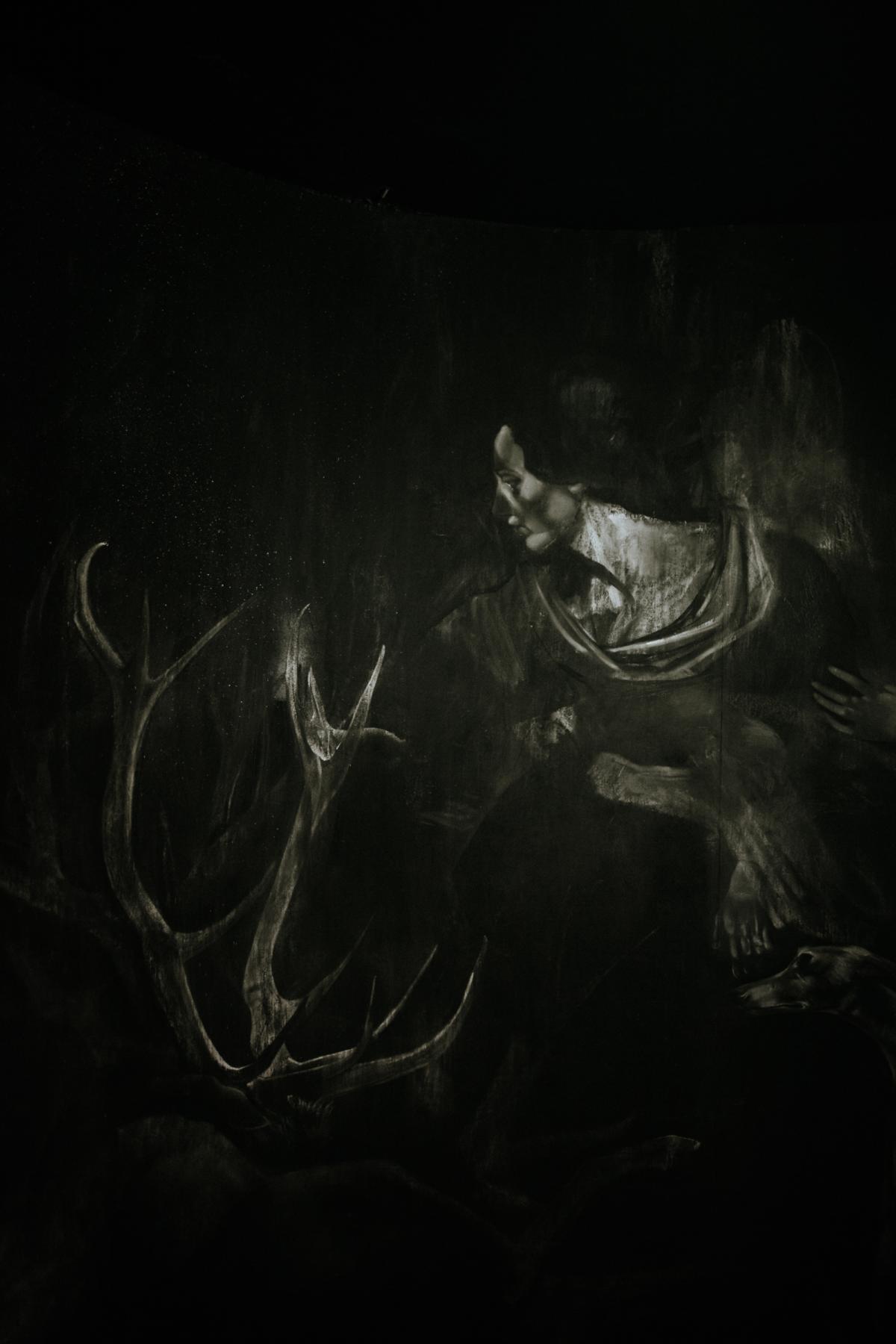

It is exactly this chronicle record as well as reports of aristocratic collections of severed limbs, noses and ears of the Roma captured during such battues, subsequently exhibited in cabinets of curiosities or in palace rooms alongside hunting trophies, recoverable from the sources as late as mid-19th century, which has inspired the work of Krzysztof Gil.

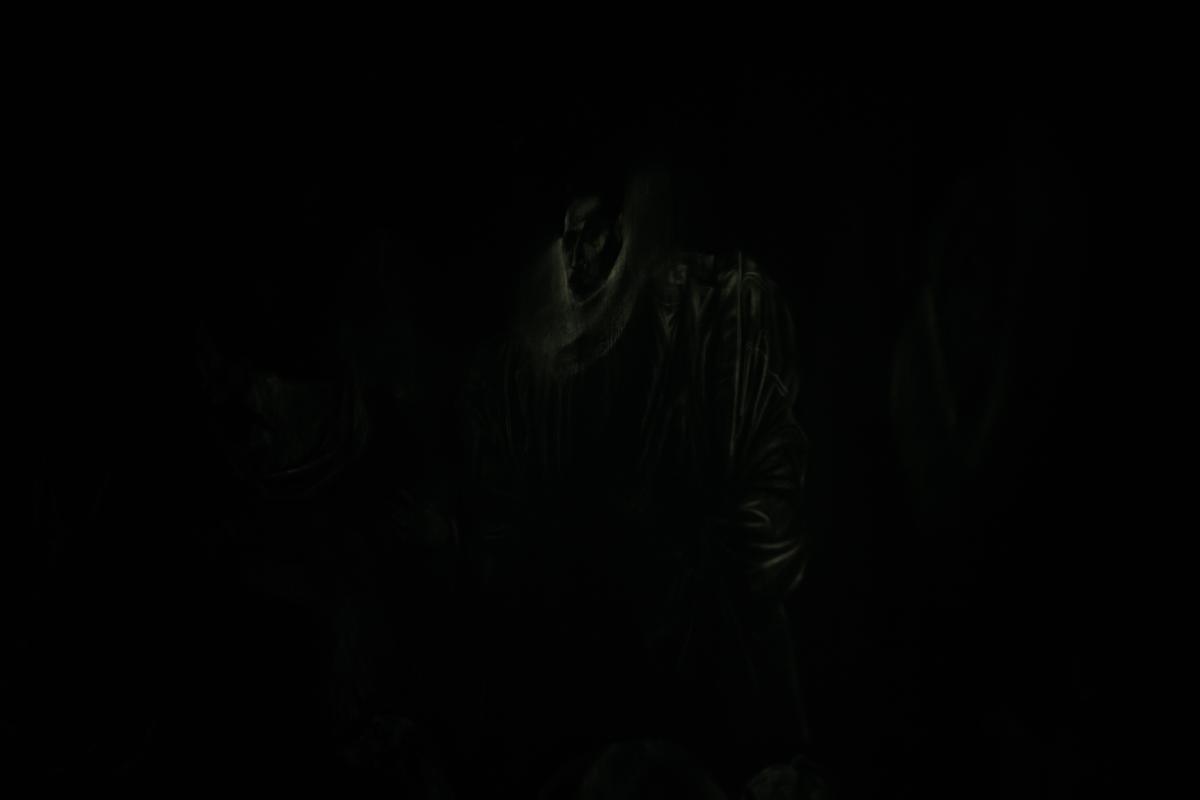

The Polish-Romani artist has produced a species of installation, composed of a cubical room of his design and making, and of sound. In its form, dimensions and execution technique, the cubic shed put together from accidental pieces of wood and fabric alludes to traditional, humble, temporary houses erected by the legally and socially marginalised Roma. On the other hand, repeating the paradigmatic form of a gallery white cube, it constructs a literally Chinese-box situation, whence it positions the audience. Since the cubical installation, upon entrance, turns out to a self-contained exhibition space, whose darkened interior appears to be a dialectical antithesis of the space of a gallery.

Inside the one-chamber room, Krzysztof Gil installed a panoramic painting. The cylindrical panorama consists of a majestic and monumental, white-crayon drawing on black background, representing a scene of game display. The image, which follows the representational convention for hunting trophies, is composed of likenesses of genteel women and men, clothed in modern hunters’ and their female companions’ apparel. All images used by the artist have been appropriated from painting of the old masters. In the surrounding darkness, the light rhythmically reveals characters, whose prototypes become identifiable as members of the surgeons’ guild depicted by Rembrandt, for example, or as St. Irene attending to the body of St. Sebastian from Georges de la Tour’s painting. The composition centre holds, amidst hunted game, a de-faced – as profil-perdu painted – torso of an anonymous, shut-down Roma.

Krzysztof Gil’s use of the convention of appropriation, historicising his piece, is at once a sarcastic comment, in the spirit of Reger from Thomas Bernhard’s Old Masters, on European art as a history painted in bright colours, and an accusation levelled against it. On the other hand, thanks to the sound accompanying the visible, a remote history becomes juxtaposed to the contemporary and to the artist’s private, family history.

The sound-track accompanying our viewing of his panorama is fragments of a record of a conversation Krzysztof Gil conducted with his grand-mother. She tells the story of her father – a musician and a brick-layer – murdered after WWII in the Podhale region, because he had had the audacity to make a remark about a poorly executed work to his Polish co-workers. Upon arrival on the scene of crime, the militiamen and doctors found the event to be a misadventure. The perpetrators went unpunished.

The artist’s family history, which has been combined here with an event described in a 17th-century chronicle, demonstrates that the ritual Heidenjachten are not really a closed chapter of history, and that anti-Roma violence remains a notorious occurrence. It is confirmed also by the exhibition title, which we have borrowed from a contemporary photograph found on the Internet, representing a caption on a wall of a Polish city. The paint appeared to still be wet.

Imprint

| Artist | Krzysztof Gil |

| Exhibition | Welcome to the Country Where the Gypsy’s Been Hunted |

| Place / venue | Henryk Gallery, Krakow |

| Dates | 1 – 25 June 2018 |

| Curated by | Wojciech Szymański |

| Photos | StudioFILMLOVE, all images copyright and courtesy of the artist and Henryk Gallery, Krakow (Poland) |

| Website | henrykgallery.com/en/ |

| Index | Henryk Gallery Krzysztof Gil Wojciech Szymański |