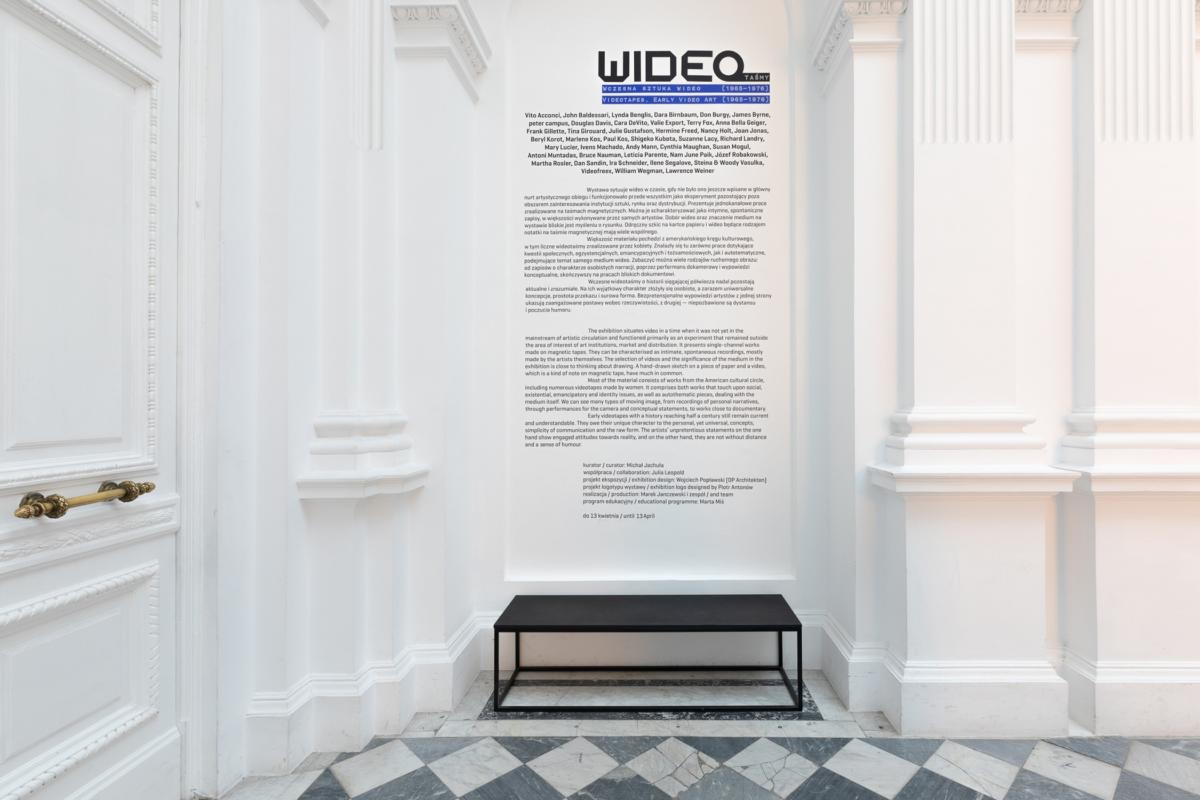

‘Videotapes. Early Video Art (1965–1976)’ at Zachęta – National Gallery of Art

text by Michał Jachuła

Video, an art form with little tradition and no ritual grounding . . ., is the perfect medium for conceptual artists whose work questions the nature of art itself.[1]

David Ross

The beginnings of video art in the mid-1960s coincided with the flourishing of conceptual practices, performance, dematerialisation of art and activities, in which the process was often more important than the final work. Its existence in circulation of art is, on the one hand, connected with the exhaustion of the formula of ‘old’ media, mainly painting and sculpture, on the other hand, with technological possibilities opening new perspectives for creativity. From the beginning, video art was not limited to the playback of recorded material on TV screens, but evolved towards video sculpture, video installations and activities taking place in real time, including the use of TV cameras. It is linked to television by technology — the signal recorded by the camera is transmitted and then played on a TV set as picture and sound, and VCRs and analogue image recording tapes have been used by television for several decades. At the same time, however, the development of video has been accompanied from the very beginning by critique of television as a mass medium serving the viewers a picture of the world built on consumerism. As an artistic medium and, more broadly, as a means of expression employing a moving picture with sound, it was used in cable television channels that served as an alternative to public broadcast television. It became a democratic, grassroots voice of activists and self-organising communities who wanted to talk about important issues from a different perspective than mainstream media, including television entangled in different political and other interests.

Researchers unanimously claim that there would not have been video art if not for the introduction of portable video equipment to the American market in the 1960s and its large-scale popularisation. The biggest role in the story was played by the Sony Portapak camera — portable, affordable, relatively lightweight and easy to use, it quickly became a new tool for artists in their creative work. Thanks to the use of cheap reusable tapes, it was possible to easily record images along with sound. Hermine Freed explains why visual artists took to the technology so eagerly: ‘. . . the Portapak would seem to have been invented specifically for use by artists. Just when pure formalism had run its course; just when it became politically embarrassing to make objects, but ludicrous to make nothing; . . . just when it began to seem silly to ask the same old Berkeleyan question, “If you build a sculpture in the desert where no one can see it, does it exist?”; . . . just when we understood that in order to define space it is necessary to encompass time . . . — just then the Portapak became available.’[2]

The current exhibition, in accordance with the title, situates video in a time when it was not yet in the mainstream of artistic circulation and functioned primarily as an experiment that remained outside the area of interest of art institutions, market and distribution. It includes works by 42 authors (including those considered to be video art pioneers) — single-channel recordings on magnetic tapes. It thus focuses on an ‘orthodox’ and narrow understanding of the medium, omitting other image records classified as video art in the literature on the subject (such as 16 mm, 35 mm, Super 8 film or broadcasts). Most of the presented material is works from the American cultural circle, including numerous videotapes made by women. They can be characterised as intimate, spontaneous recordings, mostly made by the artists themselves. The selection of videos and the significance of the medium itself in the exhibition is close to thinking about drawing. ‘The camera is a pencil’,[3] Douglas Davis wrote. A hand-drawn sketch on a piece of paper and a video, which is a kind of note on magnetic tape, have much in common. In the works shown at the exhibition, interference by means of editing is slight or completely absent, when the recordings were made in one shot. What we can see here are above all works that have not been computer-processed and which have not undergone procedures that distort the image.

Watch a video guided tour of the exhibition Videotapes. Early Video Art (1965–1976)

For creators of early video works, the ability to record and see themselves on a TV screen was important. As in the case of self-portraits created using traditional media, this was not only due to the desire to immortalise their image, but also for practical reasons — the availability of a ‘model’ at any time. Many artists thus played the roles of actor, director, camera operator and narrator simultaneously, weaving their tale in completely different conditions than costly productions using celluloid film. The issue of the difference in approach to working in both technologies recurs in artists’ statements, including Japanese artist Shigeko Kubota: ‘I always thought video is very organic, like brown rice. . . . Compared to film. Because film is very chemical. The whole process is chemical. . . . But video is very organic. You play back and you see it.’[4]

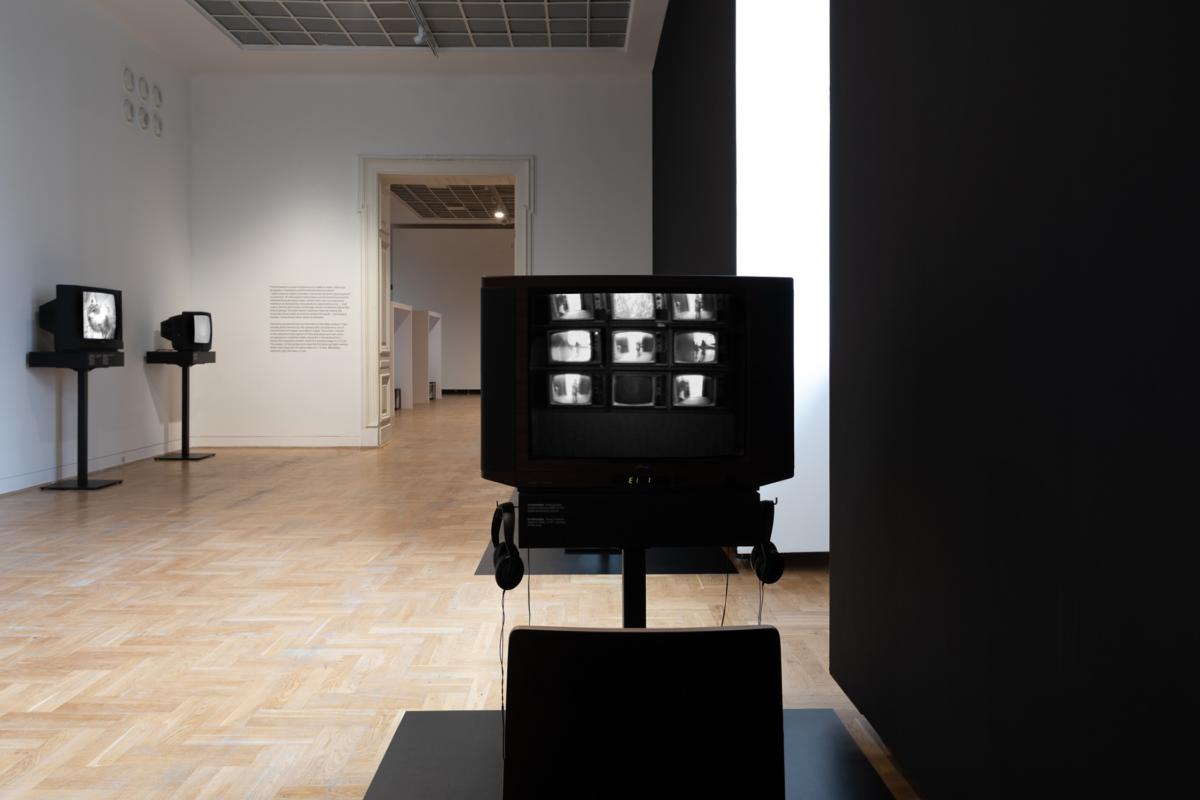

The exhibition presents works touching upon social, existential, emancipatory and identity issues, as well as autothematic ones, dealing with the medium itself. One can distinguish here many types of moving image: from recordings of personal narratives, through performances for the camera and conceptual statements, to works close to documentary. The tapes have been divided into four groups. In the first room are those in which the artists’ fascination with the ability to work with the moving picture, also present on the screens of TV sets recorded on tape, is clearly visible. The moving picture within the moving picture appears in works such as Joan Jonas’ Left Side, Right Side (1972), Linda Benglis’ Now (1972), as well as James Byrne’s Translucent and Both (both from 1974). Others are an expression of interest in the illusory nature of time and space, as well as real reality as opposed to mediated reality. In Beryl Korot’s Lost Lascaux Bull (1973), the drawing of the bull appears against a background of flames and ultimately vanishes in the fire, only to reappear a moment later in an analogous situation on a TV screen. Ira Schneider’s TV as a Creative Medium (1969) is a documentation of a 1969 exhibition of the same title at the Howard Wise Gallery in New York, in which the artist participated alongside Nam June Paik and Frank Gillette, and which became one of the key events in the history of the video scene. Artists also devote attention to the Sony Portapak camera itself — The Portapak Conversation (1973) made by the Videofreex collective and Douglas Davis’ The Cologne Tapes (1974) — and to the phenomenon of the perception of the image using simple technical tricks, such as Dan Sandin in the video Triangle in Front of Square in Front of Circle in Front of Triangle (1973).

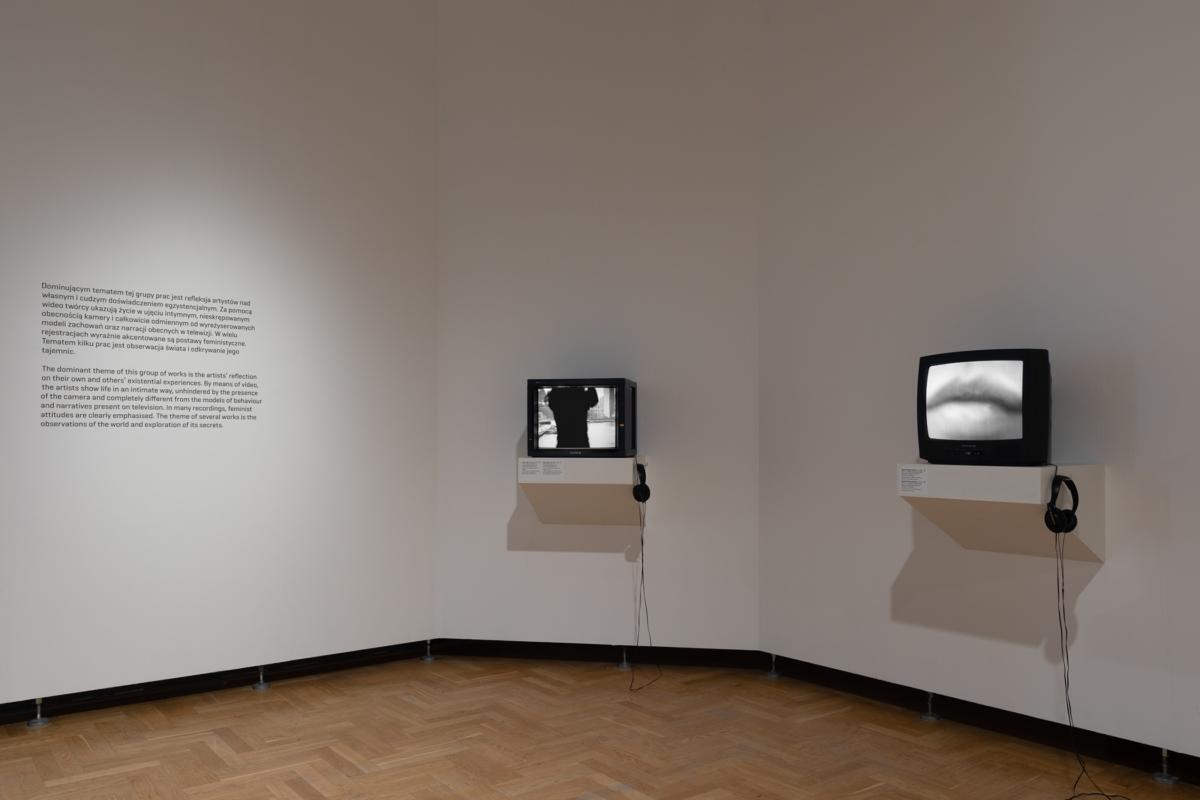

The next group is composed of videotapes with the dominant theme of reflecting on one’s own and others’ existential experience. In many of them, feminist attitudes are clearly emphasised. Julie Gustafson’s video The Politics of Intimacy (1972) presents ten women of various ages talking about their own sexuality, feelings and behaviour related to their intimate life. Hermine Freed’s work Family Album (1973), a kind of retrospective journey, confronts the author’s memories of childhood and adolescence with her adult life. Cara DeVito’s dramatic video, Ama l’uomo tuo (Always Love Your Man) (1975) is a portrait of the artist’s grandmother. In turn, Shigeko Kubota’s My Father (1973–1975) is a personal record of mourning. The observation of the world and its mysteries has become the subject of contemplative works Attention, Focus, and Motion (1975) by Mary Lucier, Lightning (1976) by Paul and Marlene Kos, and Let It Be (1972) by the duo Steina & Woody Vasulka.

In the next room, we can see works created by classics of conceptualism and artists theoretically and practically exploring the issues of language and the various systems they construct, including John Baldessari’s I Am Making Art (1971), Terry Fox’s Children’s Tapes (1974), and Valie Export’s Visual Text: Finger Poem (1968–1973). In his April 21, 1973, Don Burgy walks through a forest and talks about the analogy between it and the system of art, in which artists function like trees. In Semiotics of the Kitchen (1975), Martha Rosler demonstrates the daily life of a woman in a household using kitchen utensils, while Lawrence Weiner defines the conditions for creating art in Beached (1970). Together with the tapes of American artists, the work of Józef Robakowski — a key artist in the development of video art in Poland — is shown in this room. In the conceptual-performance action On the Line (I’m Walking, I’m Jumping, I’m Running) (1976), Robakowski illustrates a story in which the video camera has become an extension of the artists’ body.

The last set includes tapes with recordings of a broad range of artists’ activities. They resound with the issues of the characters’ carnality, identity and individuality in situations arranged in front of the camera. Many of them are an expression of feminist views, such as works by Letícia Parente, Suzanne Lacy, Tina Girouard, Cynthia Maughan and Susan Mogul. Also presented here is a selection of William Wegman’s videos from 1970–1976, made with a great sense of humour. Next to them, we can see several works featuring a clothing motif. These include Scar/Scarf (1973–1974), Razor Necklace (1975) and The Way Underpants Really Are (1975) by Cynthia Maughan, short sequences in which the artist tries to cover the scar on her neck, wears the titular necklace and underwear with holes in it. Susan Mogul’s Dressing Up (1973) — which may be called a reverse strip-tease — is accompanied by the artists’ monologue about clothing purchased at a great price. And finally, there is Nam June Paik’s Button Happening (1965) — the artist’s oldest known and preserved video tape documents the action of buttoning and unbuttoning a coat. The artist, associated with Fluxus, jokingly expresses here a distrustful attitude towards the elite art world defining what is ‘real art’. The piece by the ‘father of video art’, created 55 years ago, is also the oldest work presented in the exhibition.

Early video tapes, although they are now historical works, still seem fascinating. They owe their unique character to the personal, yet universal, concepts, simplicity of communication and the raw form. The artists’ unpretentious statements on the one hand show engaged attitudes towards reality, and on the other hand, they are not without distance and a sense of humour. And that is why they are still timely and understandable.

[1] David Ross, untitled text, Video Tape Review 83, 1983 (Video Data Bank).

[2] Hermine Freed, ‘Where Do We Come From? Where Are We? Where Are We Going?’, in Ira Schneider, Beryl Korot, Video Art: An Anthology, New York and London: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1976, pp. 210.

[3] Douglas Davis, ‘Manifesto Exhibition at the Everson Museum’, Syracuse, New York, December 1972, from the text ‘The End of Video: Vapor (1978)’, in Video Writings by Artists (1970–1990), ed. Eugeni Bonet, Milan: Mousse Publishing, 2017.

[4] Shigeko Kubota in conversation with Jeanine Mellinger, in Shigeko Kubota: An Interview, video tape, Chicago: Video Data Bank, 1983.

Imprint

| Artist | Vito Acconci, John Baldessari, Lynda Benglis, Dara Birnbaum, Don Burgy, James Byrne, peter campus, Douglas Davis, Cara DeVito, Valie Export, Terry Fox, Anna Bella Geiger, Frank Gillette, Tina Girouard, Julie Gustafson, Hermine Freed, Nancy Holt, Joan Jonas, Beryl Korot, Marlene Kos, Paul Kos, Shigeko Kubota, Suzanne Lacy, Richard Landry, Mary Lucier, Ivens Machado, Andy Mann, Cynthia Maughan, Susan Mogul, Antoni Muntadas, Bruce Nauman, Letícia Parente, Nam June Paik, Józef Robakowski, Martha Rosler, Dan Sandin, Ira Schneider, Ilene Segalove, Steina & Woody Vasulka, Videofreex, William Wegman, Lawrence Weiner |

| Exhibition | Videotapes. Early Video Art (1965–1976) |

| Place / venue | Zachęta – National Gallery of Art, Warsaw |

| Dates | 15 February – 13 April 2020 |

| Curated by | Michał Jachuła (collaboration: Julia Leopold) |

| Photos | Anna Zagrodzka |

| Website | www.zacheta.art.pl |

| Index | Andy Mann Anna Bella Geiger Antoni Muntadas Beryl Korot Bruce Nauman Cara DeVito Cynthia Maughan Dan Sandin Dara Birnbaum Don Burgy Douglas Davis Frank Gillette Hermine Freed Ilene Segalove Ira Schneider Ivens Machado James Byrne Joan Jonas John Baldessari Józef Robakowski Julia Leopold Julie Gustafson Lawrence Weiner Letícia Parente Lynda Benglis Marlene Kos Martha Rosler Mary Lucier Michał Jachuła Nam June Paik Nancy Holt Paul Kos peter campus Richard Landry Shigeko Kubota Steina & Woody Vasulka Susan Mogul Suzanne Lacy Terry Fox Tina Girouard Valie Export Videofreex Vito Acconci William Wegman Zachęta – National Gallery of Art |