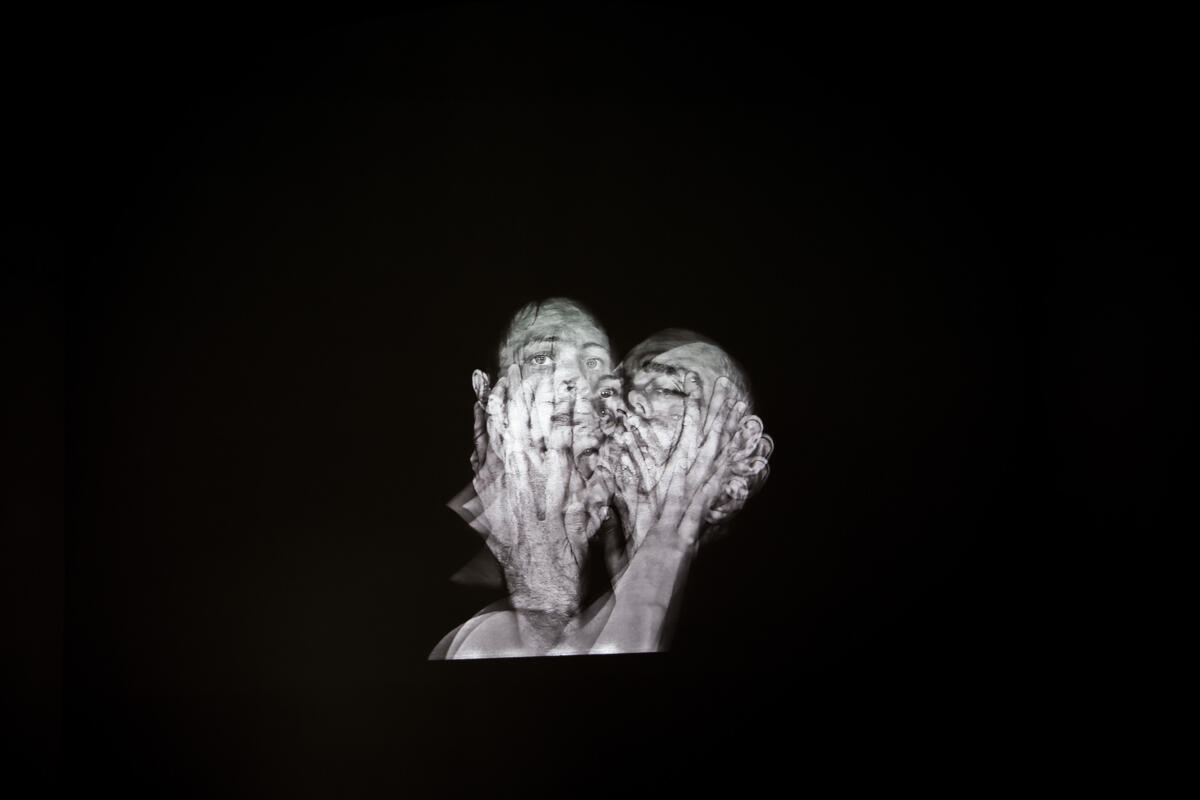

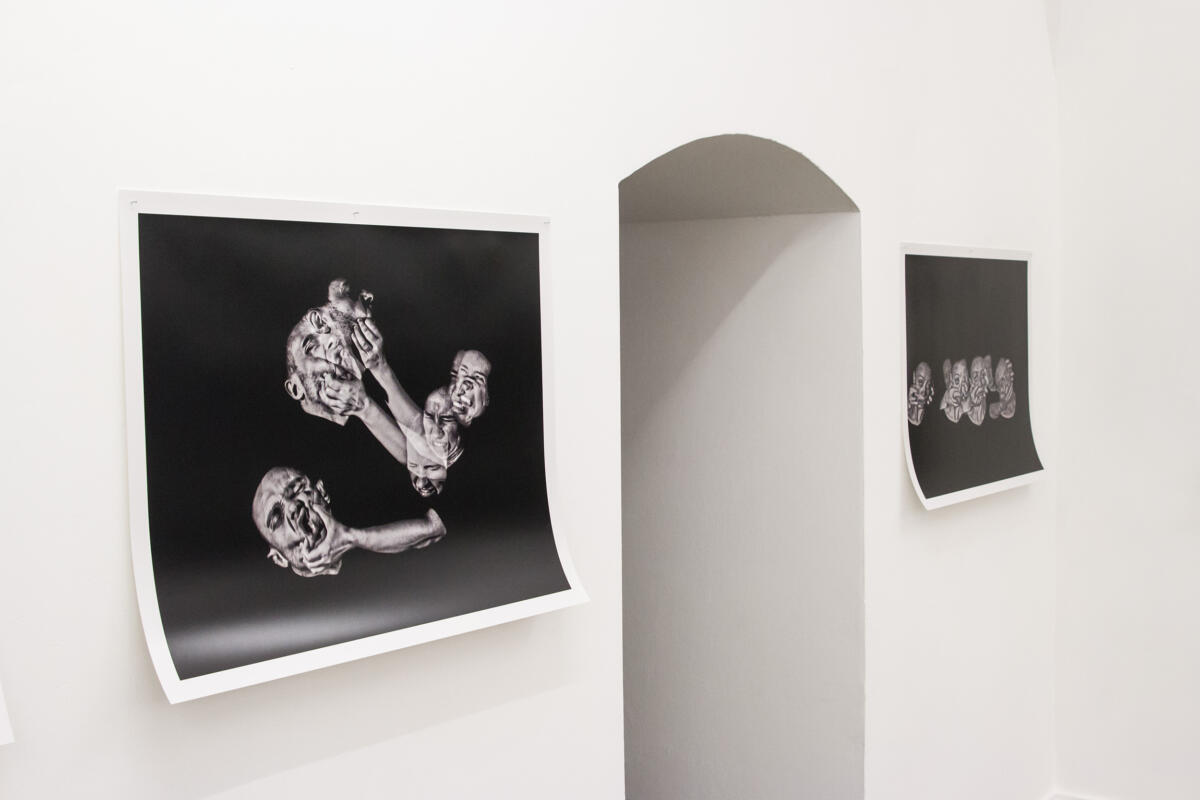

[EN/PL] ‘The Pleasures of Ordering Evil’ by Artur Żmijewski at City Art Gallery of Kalisz

![[EN/PL] ‘The Pleasures of Ordering Evil’ by Artur Żmijewski at City Art Gallery of Kalisz](https://blokmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/jns-201015-165709-9630-1200x800.jpeg)

[EN]

Violence is committed all around us – we can see its traces everywhere, its permanent and temporary effects. Everywhere, i.e. in the visual landscape that surrounds us. Human violence against people, violence against things – against the material world created by the human – and violence against nature: the earth, animals, plants.

Watching the effects of this violence, the damage and the distortions it causes, is the beginning of the work. From industrial destruction, coercion of people, to the effects of violence in war and the destruction of nature. Human actions leave traces – transformed landscapes, deformed items, mutilated bodies, deformed nature.

My artistic activity would be to “abstract” a visual formula from these acts of destruction, certain shapes which, although abstract, would carry the trauma of devastation.

I am thinking of something like a mathematical formula or pattern of violence, abstracted, distilled from the shape of things and bodies and endowing it with a visual form.

During a walk around Warsaw’s Muranów, I found fragments of metal structures in the dug up ground. I am absolutely certain that they came from the burnt and demolished ghetto. They were small fragments – I was looking at them and I had the feeling that their twisted form carried a record of destruction. Undoubtedly, it is a trace of violence, but also that the violence continues to exist in this object. It was not erased by time, it has not been forgotten – this object is a victim of unburied, unforgettable violence. It comes out of the ground and retains the event that deformed its shapes. I thought that this piece of metal clamp, some structural element of the house, looked today as it looked 70 years ago, when the house was on fire and then collapsed. There is only more rust on that piece of metal. At the same time, the shape of the object was not dramatic – it was twisted and damaged, but not frightening. It was not a mutilated body – although at the same time it was a mutilated body.

This duality intrigued me, I tried to guess the purpose of this piece of metal, maybe its location in the structure of the building. I thought about the fire in which it was bending until the structure collapsed. It was all in this object – and yet, because I couldn’t quite see how it was destroyed – there was something abstract about it. As if violence reduced to a symbol of violence, an act of destruction that talks about itself through an object yet still hides a lot. So much that the violence itself is reduced to an abstract form, a suggestive shape.

These meditations led me to ask if I could do something like a study of violence, the matter of which were objects and bodies that had been subjected to violence. By escaping realism or literal representation, could I reduce the act of violence to a recognizable shape – to a legible symbol that would also be something more than a symbol? A symbol, which would be, and simultaneously would not be, a mutilated body, a devastated object. A witness and a symbol of his own harm. There are objects that are at the same time a “body that suffered violence,” a witness to the violence that was perpetrated on it, and a symbol of violence. Take for example the tower of the Memorial Church on Breitscheidplatz in Berlin. What remains of the church, which was destroyed by bombs, is a ruined tower, standing to this day and not rebuilt. However, it is not abstract – it tells too much and reveals too much. I, however, would be striving for a kind of symbolized form that is completely out of context, be it wars or catastrophes, or human meanness.

It is as if I am looking for a certain universality or repetition in the forms which violence leaves behind. Something, which could be read when made universal. Something, which the viewer could see and understand from the pictures and objects. And which would contain a certain generality – and the singularity of trauma and fear.

I am also thinking of nature – raped and exploited – about the traces of destruction within itself. About how violently we treat nature, plants, and animals. It is also the nature that is being destroyed that could become a matrix for looking for a certain universal formula of violence against her, against Earth.

Is it getting anywhere? What is the point of doing this? It seems to me that it is just considering it, remembering the violence and constantly recalling its effects so that it does not elude us. So that the traces are not obliterated. Invoking the presence of what is extremely threatening, though overshadowed, questioned, ignored. Meditation and showing – one more way, by one more person.

I think we already live in a world deeply traumatized by the pervasiveness of rape and violence. It permeates reality and is present everywhere with varying intensity. Its traces – above all, helplessness towards it – for example, when violence is used by the most important politicians – stay with us and increase the stress. Violence has become naturalized and universal. Dealing with it is definitely dealing with one‘s own helplessness.

[PL]

Przemoc dzieje się wokół nas – wszędzie widzimy jej ślady, jej trwałe i nietrwałe skutki. Wszędzie tzn. w otaczającym nas krajobrazie wizualnym. Przemoc ludzi wobec ludzi, przemoc wobec rzeczy – wobec materialnego świata stworzonego przez człowieka – i przemoc wobec natury: ziemi, zwierząt, roślin.

Przyglądanie się skutkom tej przemocy, zniszczeniom i zniekształceniom jakie czyni, jest początkiem pracy. Począwszy od zniszczeń przemysłowych, gwałtu na ludziach, do wojennych skutków przemocy i do zniszczeń w przyrodzie. Ludzkie działania zostawiają ślady – przekształcone krajobrazy, zdeformowane rzeczy, okaleczone ciała, zdeformowana przyroda.

Moje działanie artystyczne miałoby polegać na „wyabstrachowaniu” z tych zniszczeń jakiejś wizualnej formuły, pewnych kształtów, które choć abstrakcyjne, to jednak przenosiłyby traumę dewastacji.

Myślę o czymś w rodzaju matematycznej formuły czy też wzoru przemocy, wyabstrachowanego, wydestylowanego z kształtu rzeczy i ciał i nadania mu wizualnej formy.

Na spacerze po warszawskim Muranowie, w rozkopanej ziemi, znalazłem fragmenty metalowych konstrukcji. Na 100% pochodziły ze spalonego i wyburzonego getta. Były to niewielkie fragmenty – przyglądałem się im i miałem poczucie, że ich pogięta forma przenosi zapis zniszczenia. Niewątpliwie jest śladem przemocy, ale też że przemoc wciąż trwa w tym obiekcie. Że nie zatarł jej czas, nie została zapomniana – że ten obiekt jest ofiarą przemocy, która trwa niepogrzebana, niezapomniana. Wychodzi z ziemi i zatrzymuje w sobie zdarzenie, które zdeformowało jego kształty. Myślałem, że ten fragment metalowej obejmy, jakiś konstrukcyjny element domu, wygląda dziś tak, jak wyglądał 70 lat temu, gdy dom płonął, a później się zawalił. Jest na tym kawałku metalu tylko więcej rdzy. Jednocześnie kształt przedmiotu nie miał w sobie dramatyzmu – był pogięty i zniszczony, ale nie przeraźliwy. Nie było to okaleczone ciało – choć jednocześnie było to okaleczone ciało.

Ta dwoistość zaciekawiła mnie, starałem się odgadnąć przeznaczenie tego fragmentu metalu, może jego umiejscowienie w konstrukcji budynku. Myślałem o ogniu, w którym się wyginał, aż konstrukcja runęła. Wszystko to było w tym obiekcie – a jednocześnie przez to, że nie mogłem dokładnie rozeznać się w tym jak został zniszczony – było w nim coś abstrakcyjnego. Jakby przemoc sprowadzona do symbolu przemocy, akt zniszczenia, który opowiada się poprzez przedmiot, a jednocześnie wciąż wiele zakrywa. Tak wiele, że sama przemoc sprowadzona jest do abstrakcyjnej formy, sugestywnego kształtu.

Te medytacje doprowadziły mnie do pytania, czy mógłbym zrobić coś w rodzaju studium przemocy, którego materią były przedmioty i ciała, które przemocy doznały. Czy uciekając od realizmu, czy od dosłownego przedstawienia, mógłbym sprowadzić akt przemocy do rozpoznawalnego kształtu – do czytelnego symbolu, który też byłby czymś więcej niż symbolem. Który byłby i nie byłby jednocześnie ciałem okaleczonym, przedmiotem zdewastowanym. Świadkiem i symbolem własnej krzywdy. Istnieją obiekty, które są jednocześnie „ciałem, które doznało przemocy”, świadkiem przemocy, jakiej na nim dokonano, i symbolem przemocy. Niech za przykład posłuży wieża Kościoła Pamięci na Breitscheidplatz w Berlinie. Ze zniszczonego bombami kościoła pozostała zrujnowana, stojąca do dziś i nie odbudowana wieża. Ona jednak nie jest abstrakcyjna – zbyt wiele opowiada i zbyt wiele odsłania. Ja jednak zmierzałbym do czegoś w rodzaju zsymbolizowanej formy, która jest całkowicie oderwana od kontekstu, czy to wojen, czy katastrof, czy ludzkiej podłości.

To tak, jakbym szukał pewnej uniwersalności, czy powtarzalności w formach jakie zostawia za sobą przemoc. Czegoś, co zuniwersalizowane, dałoby się odczytać. Co widz mógłby zobaczyć i pojąć z obrazów i przedmiotów. A co zawierałoby w sobie i pewną ogólność – i pojedynczość traumy, lęku.

Myślę też o naturze – gwałconej i eksploatowanej – o śladach zniszczenia w niej samej. O tym, jak przemocowo traktujemy przyrodę, rośliny, zwierzęta. To również niszczona natura mogłaby stać się matrycą do szukania pewnej uniwersalnej formuły przemocy wobec niej, wobec Ziemi.

Czy to do czegoś zmierza? Jaki jest sens takiego działania? Wydaje mi się, że jest nim samo rozważanie, pamiętanie przemocy i ciągłe przywoływanie jej skutków, żeby to nie umykało. Żeby ślady nie zostały zatarte. Przywoływanie obecności tego, co niesłychanie zagrażające, chociaż usuwane w cień, zagadywane, lekceważone. Medytacja i pokazywanie – w jeszcze jeden sposób, przez jeszcze jedną osobę.

Myślę, że już żyjemy w świecie głęboko straumatyzowanym wszechobecnością gwałtu i przemocy. Ona przenika rzeczywistość, jest obecna wszędzie z różnym natężeniem. Jej ślady – przede wszystkim bezradność wobec niej – np. gdy przemocy używają najważniejsi politycy – zostają w nas i pogłębiają stres. Przemoc się znaturalizowała, zuniwersalizowała. Zajmowanie się nią, na pewno jest zmaganiem się z własną bezradnością.

Imprint

| Artist | Artur Żmijewski |

| Exhibition | The Pleasures Of Ordering Evil / Miłe złego porządki |

| Place / venue | City Art Gallery of Kalisz, Poland |

| Dates | 15 October – 28 November 2020 |

| Website | tarasin.pl |

| Index | Artur Żmijewski City Art Gallery of Kalisz |