Stranger Than Paradise is the result of a collaboration between MeetFactory gallery curator Eva Riebová andindependent curator Tevž Logar, who mostly works with artists and institutions from South Eastern Europe. The exhibition reflects their joint interest in artistic approaches that demand deep personal engagement of the artist, as well as to create parallels among territories that share certain historical, political, and economic circumstances.

In light of avoiding the frame of the “Balkan exhibition”, which has appeared in contemporary art from the latenineties onwards, this exhibition – whilst presenting artistic practices from the region – turns away from creating a specific geo-political narrative, choosing instead to point out specifics that relate to the artworks’ conditionsof production.

The exhibition is conceived as an exploration of the artistic practices of artists who, in one way or another, use aspects of their private lives to mediate their artistic message. The line that divides the spheres of life and art is thus blurred, making the art direct, astonishingly honest, and utterly straightforward. A common feature of allthe works included in the exhibition is the artist’s decision to make a radical decision and directly expose their personal – or even intimate – statements, which are at the same time very precisely grounded in particular political, social or economic conditions.

The title of the exhibition is taken from Mark Požlep’s performance piece, Stranger Than Paradise, which was performed in a real social environment: the project took place as a seven- day concert tour around homes for the elderly in six countries of former Yugoslavia. The musical programme was composed of seven songs which dominated Yugoslavian popular music in the 50s and 60s, and soaked through one particular generation. The project is not only a story about Yugoslavia – it is most of all a story about society and the most intimate relationships between people.

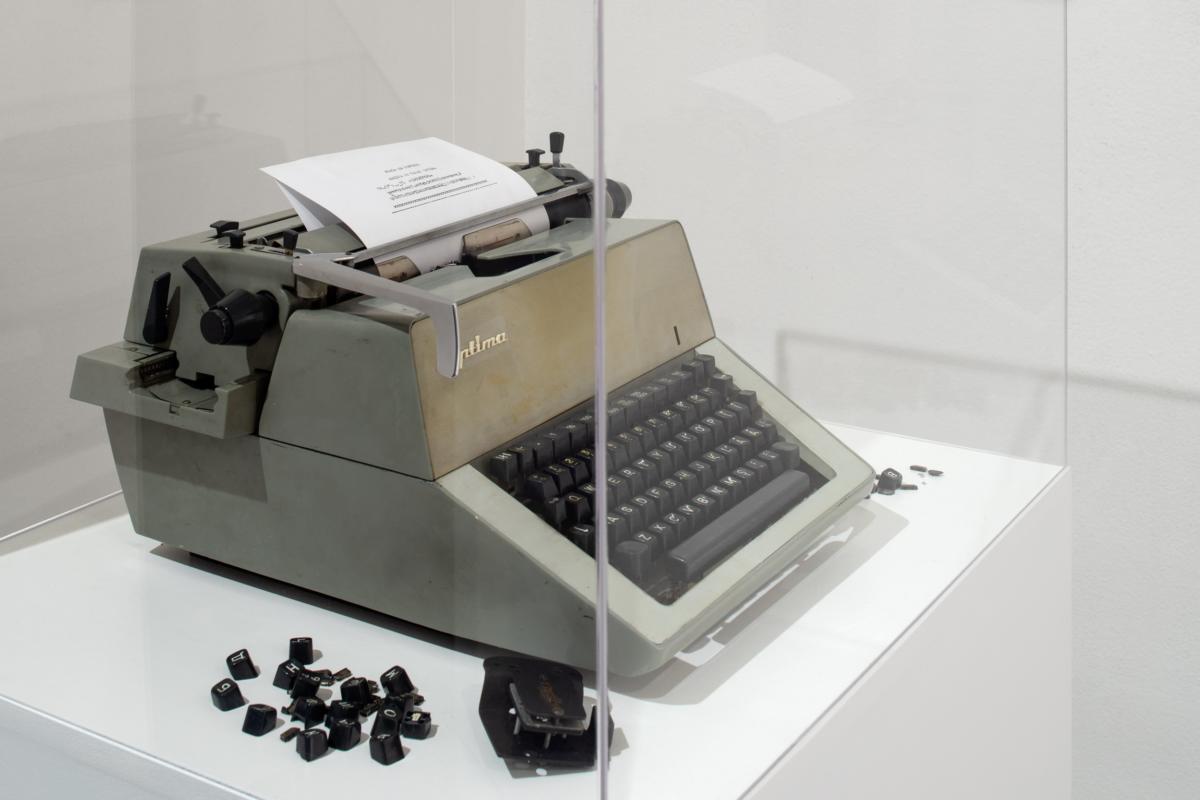

It is no different with the work of Pavel Brăila, who is often inspired by his local environment – Moldova. As the artist himself proposes, Life itself becomes the central artistic project. The artefacts which appear during this process are traces or remains, like fingerprints– they are a sort of by-product of life. Brăila’s minimal but very straightforward observations of his surroundings avoid both nationalism and nostalgia. The work presented at the exhibition, Foaia De Control, is a slow “video poem” in which an elderly man changes a typewriter keyboard from Cyrillic to Latin script. The historical context of this bizarre operation is very closely linked to the complex post-war history of Moldova. Between the wars, the Soviet Union occupied this territory. In order to break all ties to Romania, the “capitalist oppressor”, theoriginal Latin script was replaced by Cyrillic. Until 1989, it was the only official script. One of the first laws passed in Moldova after the fall of the Iron Curtain was a return to the Romanian variant of Latin script. The protagonistof Brăila’s video changed hundreds – or perhaps even thousands – of keyboards at the beginning of the nineties. On the one hand, it is an incredibly poetic gesture that creates a constant tension throughout the duration of the video, but on the other hand, this same gesture reveals a particular historical context and the aggressiveness of political ideologies that are imposed on people.

If Braila’s gesture is minimal and poetic, the works of Jasmina Cibic embody different layers that reveal thestrategies employed for the construction of national culture and identity through the arts, as well as their useon behalf of political ideologies. Through film, performance, sculpture, and installation, Jasmina Cibic’s complex approach explores the instrumentalisation of visual language, which can be understood as one of the basic elements in human communication. Her presentation within this exhibition juxtaposes her video The Nation Loves It and a series of collages and objects from the Spielraum series, which directly confronts the viewer with the investigation of questions which not only speak about the modes of systems of power, but also about the conflicts that are mutually associated to shifts of past and present cultural identities.

Cibic directly challenges the viewer on a visual level, and in a way represents a “haptic opposition” to the work of Lana Čmajčanin, who addresses the viewer through ephemeral means: non- material structures such as light, movement and sound. Unfinished Symphony was conceived as a site-specific installation in Tvrđava Brod (Brod Fortress) in Slavonski Brod, Croatia. The installation initially represented Čmajčanin’s commentary on therepetitive historical practice of violence and wars in the Balkan countries. Like the majority of Čmajčanin’s work,Unfinished Symphony is based in a particular set of geopolitical conditions, but tackles the themes with a precision that enables the liveability of the work out of its initial context. In this particular situation, it is not only about the artist’s position towards a particular topic and how this is formally translated into an artwork, but it is rather about the “void” that is created between these two entities. Čmajčanin creates a “Brechtian” situation, tearing down “the fourth wall” and directly involving the spectator in the conflict that develops between her commentary and the spectator’s personal experience of violence.

The merging of artistic and life experiences mentioned above is expressed in a quote by Tomislav Gotovac: “The thing is, I can’t really differentiate life from art.” Gotovac’s artistic expression was based on a creative andexistential persistence in identifying art and life. With this approach Gotovac demonstrated that subversion and an inclination to experiment with formal visual language leads to solutions for complex and multi-layered artistic visions. As one of the most important experimental film makers in the European historical context, Gotovac pays close attention to procedures of film directing in all of his actions, while being involved with a number of mediasuch as photography, film, and performance. The work presented here, Breathing the Air, is one of Gotovac’searliest happenings based on registering everyday acts and transposing them into public space, thus transforming common daily rhythms into something of a spectacle.

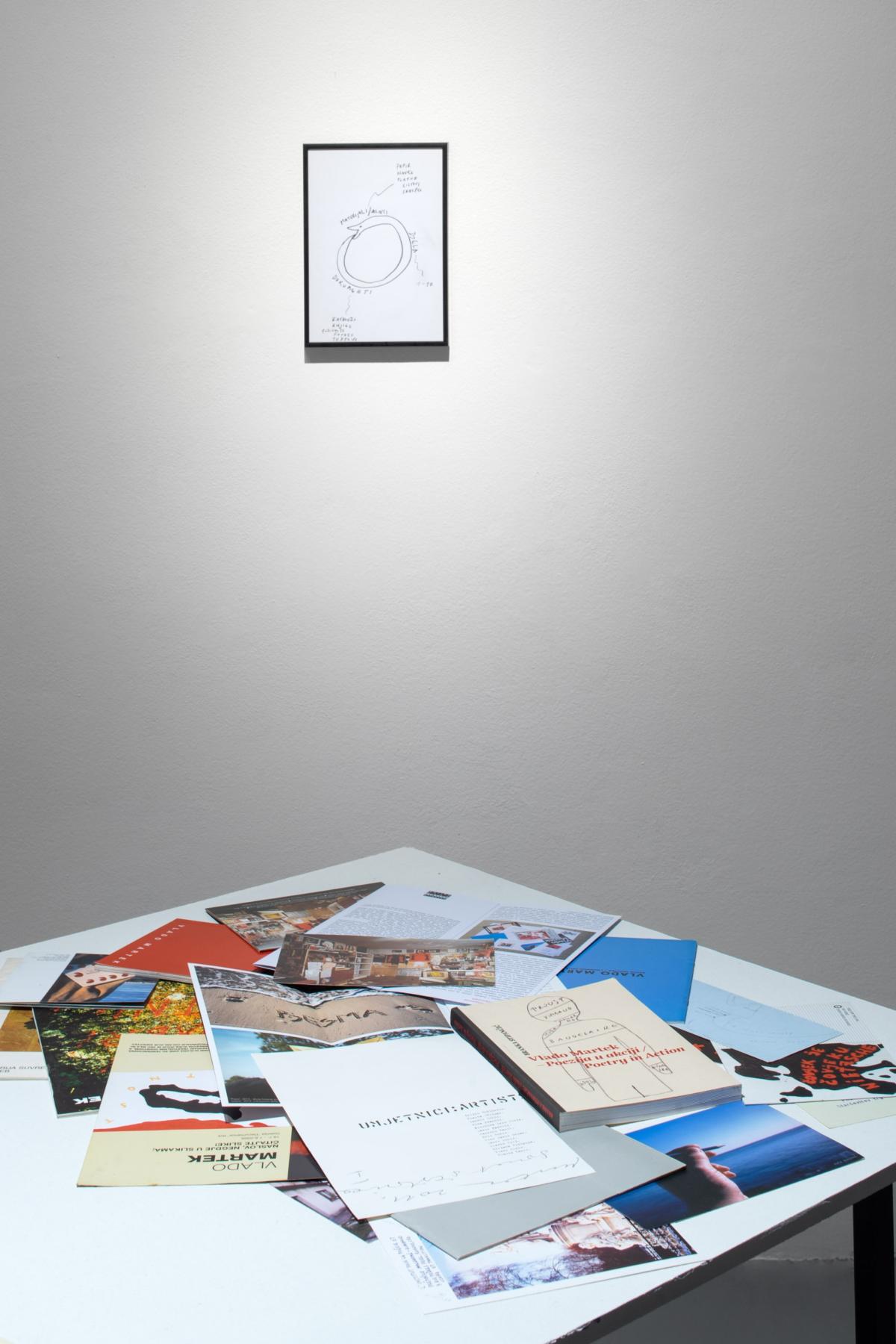

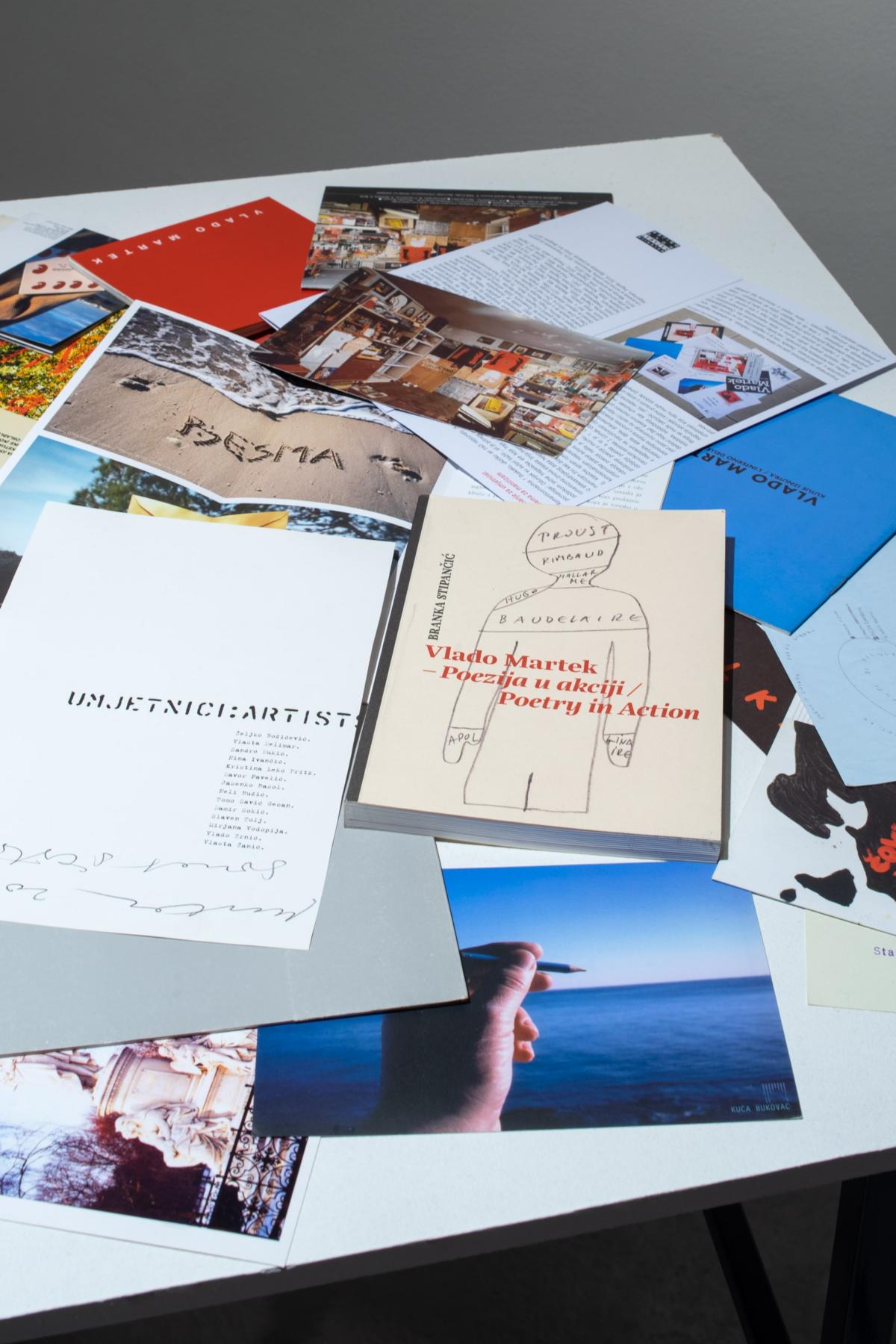

In relation to the work of Tomislav Gotovac, we can also understand the work of Vlado Martek, not just in the frame of the artistic avant-garde of 1970s Europe, but also in the context of his dedication to researching a particular medium. If Gotovac approached his work through the perception of film, with Martek it is about hisengagement with language. Martek calls himself a “pre-poet” and his work “pre-poetry”, which came to definehis artistic practice. The fundamental feature of his work is an – often humorous – crossing of language and the visual arts in drawings, photographs, objects, paintings, happenings, performances and installations, often drawing parallels with the Fluxus movement.

The presented installation evolved from Martek’s drawing, Ouroboros, which represents the artist’sunderstanding of the three phases of his artistic practice – he exposes the tools, the artworks and their documentation. At first glance this gesture can be understood as Martek’s own revision of his artistic activity. But on another level, the installation reflects Martek’s understanding of what art is in general. For him, art is notso much a result of a spray of creativity, but rather an artistic after-effect of witnessing or observing a particular situation and making a decision to transfer it to the spectator.

Witnessing a particular geo-political situation is a good description of Alban Muja’s work, which questionsstructures constituting the public while hinting at different political and social patterns based on arbitrary aesthetic moments. His work points to underlying ideological mechanisms, while directly involving the viewers in this game, thus bringing attention to the significance of their role in society. Muja creates a tension between cultural production and the mechanisms of social ideology and its myths. A very direct example of this approachis Muja’s work Tonys, which can be seen as an artist’s commentary on the conflict that arises between the oldKosovo tradition of evoking family member’s names and the invasion of new political ideologies and theirinterests that have overwhelmed the inhabitants of Kosovo. On the photograph, we see nine Kosovo Albanian children that are named after former British prime minister Tony Blair, who is considered a war hero in Kosovofor his work in ensuring Kosovo’s freedom in the late 90’s.

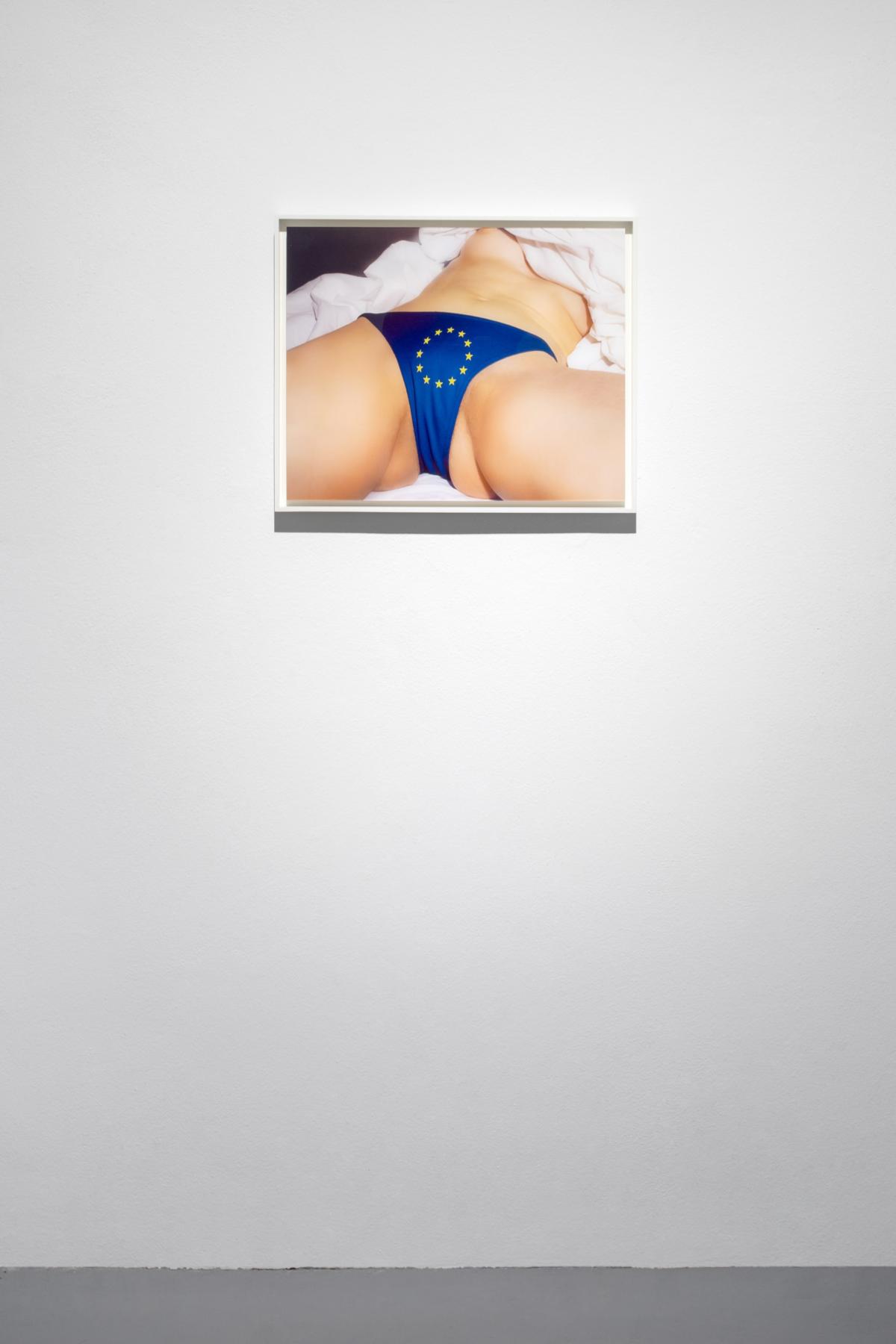

Freedom as the basic human condition is also one of the elements that can be found in the work of Tanja Ostojić.Her complex works and projects constantly confront the spectator with social reality, but they also convey theartist’s own position and feelings, which are never indifferent, but always demonstrate a strong personal opinion on a wider social issue. Ostojić works in performances and uses diverse media in artistic research, therebyexamining social configurations and relations of power. She works from the migrant woman’s perspective and the approach in her works is predominantly defined by her political and feminist positions, humour, and an integration of the recipient.

Ostojić’s work Untitled / After Courbet, L’Origine du monde recreates what was at the time a scandalous work by Gustave Courbet from 1866. Ostojić adds a new layer of controversy by posing in the same position as thewoman in the painting, wearing only a pair of blue panties which display the EU flag. Ostojić’s now seminal workcan be seen as a direct symbolic reminder of the numerous women who are abducted or tricked into illegally crossing the borders of former Eastern Europe to either work in Western Europe as sex workers or as workers earning minimal wage under slave-like conditions.

The selection of works in the Stranger Than Paradise can be seen as a juxtaposition of the artists’ intimateconfessions with which any individual can identify, but also as a frame that reflects specific conditions of production in the geo- political story of the region of South East Europe over the past five decades.

Tevž Logar, Eva Riebová

Imprint

| Artist | Pavel Brăila, Jasmina Cibic, Lana Čmajčanin, Tomislav Gotovac, Vlado Martek, Alban Muja, Tanja Ostojić, Mark Požlep |

| Exhibition | Stranger Than Paradise |

| Place / venue | MeetFactory, Prague |

| Dates | June 10 - September 2, 2018 |

| Curated by | Tevž Logar, Eva Riebová |

| Index | Alban Muja Eva Riebová Jasmina Cibic Lana Čmajčanin Mark Požlep Meetfactory Pavel Brăila Tanja Ostojić Tevž Logar Tomislav Gotovac Vlado Martek |