Let us begin by looking at who Zygmunt Rytka (1947–2018) was. Born in Warsaw, Rytka was one of the most celebrated artists of his generation. And yet he remains overshadowed by his better-known contemporaries, representatives of the Polish neo-avant-garde such as Józef Robakowski, Andrzej Lachowicz, Natalia LL, Zbigniew Dłubak, and the KwieKulik duo. Rytka came onto the scene in the 1970s, a breakthrough period in contemporary art.

Art was increasingly becoming stuck in its fossilized conceptual formulae, and this coincided with the beginnings of an acceptance of film and photography as artistic media in their own right. This placed Rytka in a group of post-conceptual artists associated with photomedialism who had, since the mid-1980s, been searching for their own creative direction. As Krzysztof Jurecki has noted, they were also laying the foundations for the Polish postmodernist art of the 1990s.[1] Although many of Rytka’s works are known to critics and considered to be cult pieces, for example S.M. Catalogue, Continual Infinity or Contact, it remains the case that both the artist and his work have been undervalued.

Could this be because of the discontinuous nature of his work? Or perhaps because he didn’t join the mainstream? Rytka certainly situated himself ahead of the mainstream, or simply avoided it, focusing instead on the sociology of art or topics associated with ecology and spirituality or the Anthropocene, which are so fashionable today. This was before his art found a wider audience as well as critical attention. During his lifetime, Rytka was actively involved in the art scene. As a member of the Polish neo-avant-garde of the last quarter of the 20th century, his work was included in the programmes of the most important cultural institutions, including Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź,[2] which presented a retrospective of his artistic output.

Zygmunt Rytka, ‘To Whom Does the Cosmos Belong?’, exhibition view, Krakow Photomonth press materials, photo: Kamil A. Krajewski / www.kamilkrajewski.com

After his death, Rytka’s context as an artist was unclear. Despite numerous critical works, publications and exhibitions, both critics and curators seem to find it hard to know how to deal with his oeuvre. His works are not included in permanent collections in the major museums. Since his death, none of the principal Polish museums and centres for contemporary art have shown interest in his legacy. There has not been a single retrospective, major or minor, of Rytka’s oeuvre. The only exception was a tribute to him in the form of several simultaneous exhibitions organized by the prestigious Association of Polish Art Photographers,[3] of which Rytka was a member.

It is significant that this survey was presented in various locations, as if to convey the multiplicity of the artistic strands that Rytka explored. In addition to the main part of the exhibition at Stara Galeria ZPAF, where masters such as Edward Hartwig and Jerzy Benedykt Dorys exhibited their work, and also the site of a monument commemorating Jan Bułhak, the father of Polish art photography, Rytka’s exhibition was also presented at Obok Galeria, located next door, the gallery formerly known as Mała Galeria ZPAF. It was here that Rytka held one of his most important exhibitions, Continual Infinity.

Certainly, the decision to locate this posthumous exhibition here places an emphasis on Rytka’s photographs. During his lifetime he was often described as a multimedia artist, thus almost denying the medium of photography, turning instead to object-based work and even performance art. This photographic turn in the reception of Zygmunt Rytka’s work prompts reflections on the artist’s legacy. Perhaps the time has come to start a discussion about Rytka: who was he, and what remains of his art for posterity? Can he hope for a life after life and the kind of immortality enjoyed by truly outstanding artists, or will he be forgotten? This is not about the involvement of friends and family who remember and who want to publicize an artist’s oeuvre. It is about treating Rytka as a symptom, or maybe even a problem for art history.

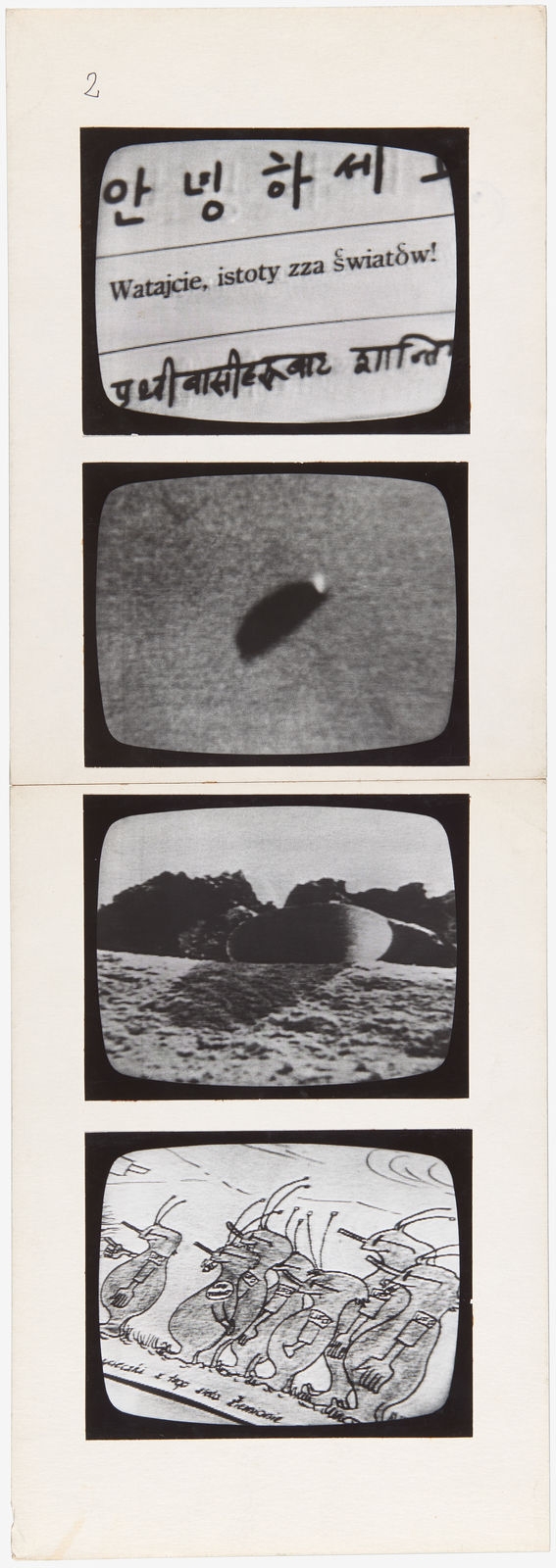

Zygmunt Rytka, ‘1980/1981’, 1980-1981

© Fundacja Sztuki Współczesnej In Situ

It seems entirely justified to place Rytka at the heart of the discourse on the art of the last quarter of the 20th century and early 21st century. After all, when we read his bios in the catalogue of the Muzeum Sztuki exhibition, there is no doubt that he was an extremely prolific artist. One from the late 1990s begins with the words: “Since 1972, he has participated in almost 100 exhibitions. Since 1974, he has had 16 solo shows”. Over time, the updated text changes, emphasizing the significantly increased interest in Rytka’s art from national and international institutions: “Since 1972, he has participated in nearly 150 exhibitions. Since 1974, he has had 32 solo shows”.[4] The importance of the artist’s work is also emphasized by a fascinating interview with Anna Maria Leśniewska in the Łódź exhibition catalogue, reprinted in the first posthumous study.[5]

S.M.

S.M. Catalogue is one of Rytka’s most interesting works, securing him an important position within the Polish neo-avant-garde classic art scene before the age of 30. It consists of panel-portraits of men and women signed with their first and last names, providing a typology that takes the viewer into the art world of the late 1970s.

Rytka situates himself at the centre of the art world, closely observing its social relationships. Some of the photos are documentations from openings at leading galleries of the day, including Remont Gallery, Foksal Gallery, Bogucki Gallery and the recently launched Mała Gallery. Rytka takes photographs as if he were a professional photographer hired to document openings. It appears to be the most non-artistic kind of commissioned photography, performed purely for a fee, demonstrating that the photographer taking the shots has no chance to be a “somebody” in this elite environment. Rytka creates a kind of atlas of artistic types, describing the network of relationships which generate artistic life. Who talks to whom, who arranges an exhibition with whom, who creates a group, collective, or a set of informal alliances. The number of combinations turns out to be limited, and the social relationships – however subjectively captured – are predictable. Rytka goes a step further and develops this somewhat sadomasochistic catalogue in an unexpected direction, juxtaposing portraits of people who never talk to each other, who avoid each other, who have no time for each other, either personally and artistically, and whose relationships are antagonistic. S.M. is an extraordinary document of that time, but also a story with a key that shows what was happening and what was unthinkable.

Zygmunt Rytka, ‘To Whom Does the Cosmos Belong?’, exhibition view, Krakow Photomonth press materials, photo: Kamil A. Krajewski / www.kamilkrajewski.com

It is the perspective of an insider – one who is looking for a place for himself in this world, asking who he gets on with and who rejects him. It is a non-artistic catalogue, although entirely dedicated to the art of the 1970s. Rytka’s atlas constitutes the foundations of his further work and explains his connections with the neo-avant-garde circles at its epicentre on the Łódź–Warsaw–Lublin axis: Strych–Mała Galeria ZPAF–Galeria Labirynt. Rytka did not stop his documentation, although he was critical about its post-conceptual framework, and redirected his focus onto punk neo-Dadaist expression. The photographs of exhibition openings and informal artistic events taken in the 1980s are a genuine document of the authentic relationships, sense of engagement, friendship and warmth which characterized Polish underground art circles during martial law.

As a work which marks the maturing of Rytka’s practice, S.M. Catalogue is intriguing when his later work is taken into consideration. It is true that Rytka continues his chronicle, but he gradually loses interest in this kind of recording as an art form. His artistic quest directs him towards new areas of reflection, serenity, contact with nature and the world. What is the explanation for this change? Why is Rytka so discontinuous, reflexive and surprising? How can we keep up with him, and how can his discontinuity be interpreted? These are key questions in the context of understanding who the artist was.

The line continuously broken

An art historian would be advised to begin any encounter with Rytka by determining whether there was any consistency in his work, or whether his development as an artist was jerky and uneven, taking place on different, often incompatible, levels.

In the introduction to the dispute concerning the exhibition and catalogue curated and produced by Krzysztof Jurecki at Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź, the artist’s friend Krzysztof Wojciechowski writes: “This exhibition is also a testimony to Zygmunt Rytka’s genuineness, his refusal to follow trends and fashions, as well as his faithfulness to the Białka River flowing rapidly in the Tatra Mountains and its sun-bleached stones”.[6] Marek Gygiel shares Wojciechowski’s opinion; the first sentence of his essay published in the 2008 exhibition catalogue reads: “The path the artist has travelled is difficult and complex, but extremely consistent”.[7]

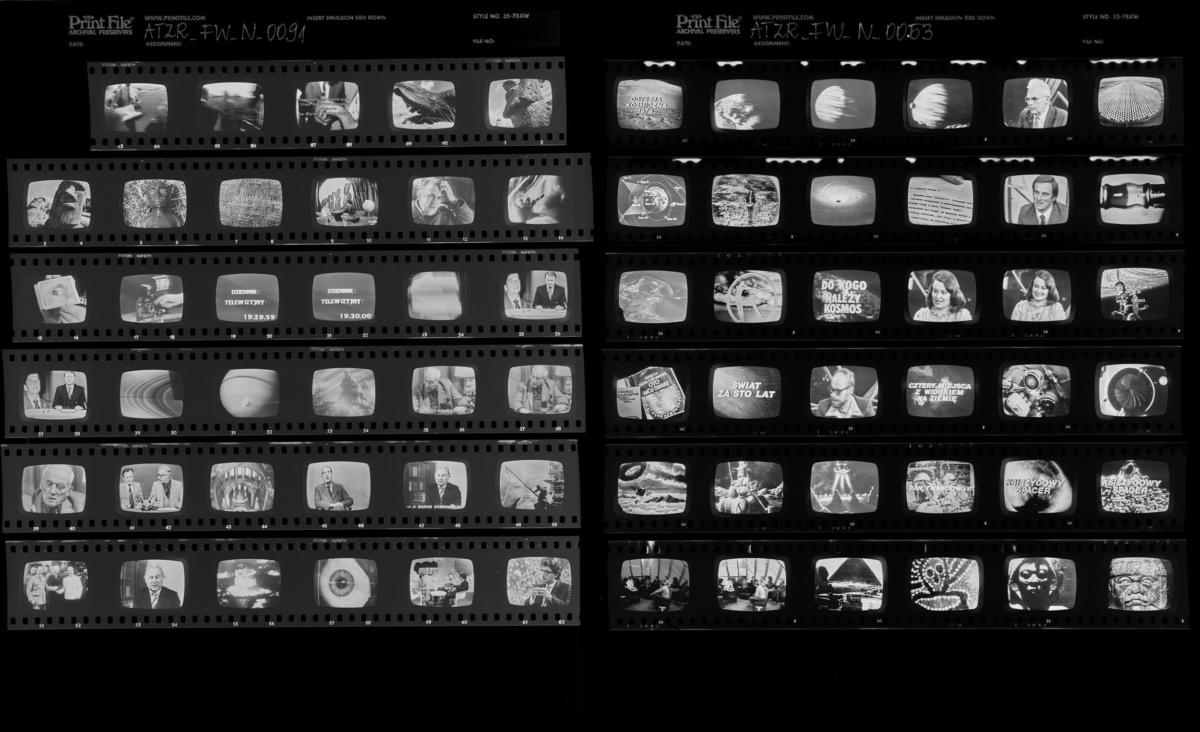

Zygmunt Rytka, ‘Fotowizja’, 1979

© Fundacja Sztuki Współczesnej In Situ

Even if we focus on the intermedia aspects of his oeuvre (the exhibition at Muzeum Sztuki) or consider the “time issue” (the exhibition at Galeria 65) as the axis of his work, it is difficult to classify Rytka as an “extremely consistent” artist. Not only does he employ a variety of media (photography, video, objects, performance art), combining several representational conventions (documentation, artistic creation), but he returns to subjects after many years.

Time Units (1971–1973) and the untitled photographs of whirlpools of water from 2005 serve as good examples here.[8] We do not need to compare Rytka with Roman Opałka – whose principal area of enquiry is the issue of time – in order to come to the conclusion that the author of Continual Infinity poses a problem for potential researchers of his work because of his lack of consistency. Where does this extraordinary cognitive error come from? The interview with Anna Maria Lesniewska mentioned above gives a hint: “All of your artistic work is linear. There are no elements in it that differ significantly from its general character. Even works created slightly outside of it function in one common line. In all your works you ask one basic question – why?”[9] Certainly, reading the texts accompanying Rytka’s work, future researchers should also ask themselves this simple, but immensely consequential question: “why?” Jerzy Busza is one critic who noted Rytka’s dynamic transformation and development early on. Rytka is the first artist whose work Busza discusses in The Twilight of Art-Photography.[10] In the essay Zygmunt Rytka – the Art of Extreme Relativity, Busza analyzes the first 15 years of Rytka’s oeuvre, emphasising the artist’s peculiar concentration. Only a friend of the artist could have written in this way. The critic presents Rytka as a young, experimental artist who succumbs easily to current trends, attempts to compete with neo-avant-gardists, loses, but keeps on trying.

This continuous questing makes Rytka an extreme relativist, which –strange as it may sound today – is a kind of perverse compliment coming from Busza. In the last paragraphs of his essay, written in the late 1980s, there is an interesting intuitive remark: “Zygmunt Rytka can be accused of extremely ruffled cognitive horizons and the implementation of activities for which the critic cannot easily find a binding element belonging to the world of traditional ‘critical tricks’. And yet, all his projects are bound together not by an arbitrary but by a dialectical attitude to the world”.[11] In Busza’s interpretation of Zygmunt Rytka’s art, it is a dialectical and not imaginary continuity. It is the opposites, not the similarities, that seem to be more cognitively interesting: the analysis of time units in relation to the search for total synthesis and understanding of the universe; the showiness and superficiality of the artistic world of the Polish neo-avant-garde of the 1970s and ‘80s contrast with his solitary meditation in Bukowina Tatrzańska; beautiful black-and-white photography versus ephemeral actions bordering on performance art and land art; superficial sociological notations in contrast to seeking the essential in Socratic philosophy and attempts to formulate his own philosophical approach… Rytka is discontinuous in his finitude. He remains outside the reach of critics and curators. Let us add to this flickering portrait of Rytka his works for the theatre, his documentations of performance art and social interactions, and even his commercial works. Rytka’s heterogeneity is not only due to his intermediality and fascination with new media – photography, film, digital recording – but also his uncertainty about the nature of artistic expression.

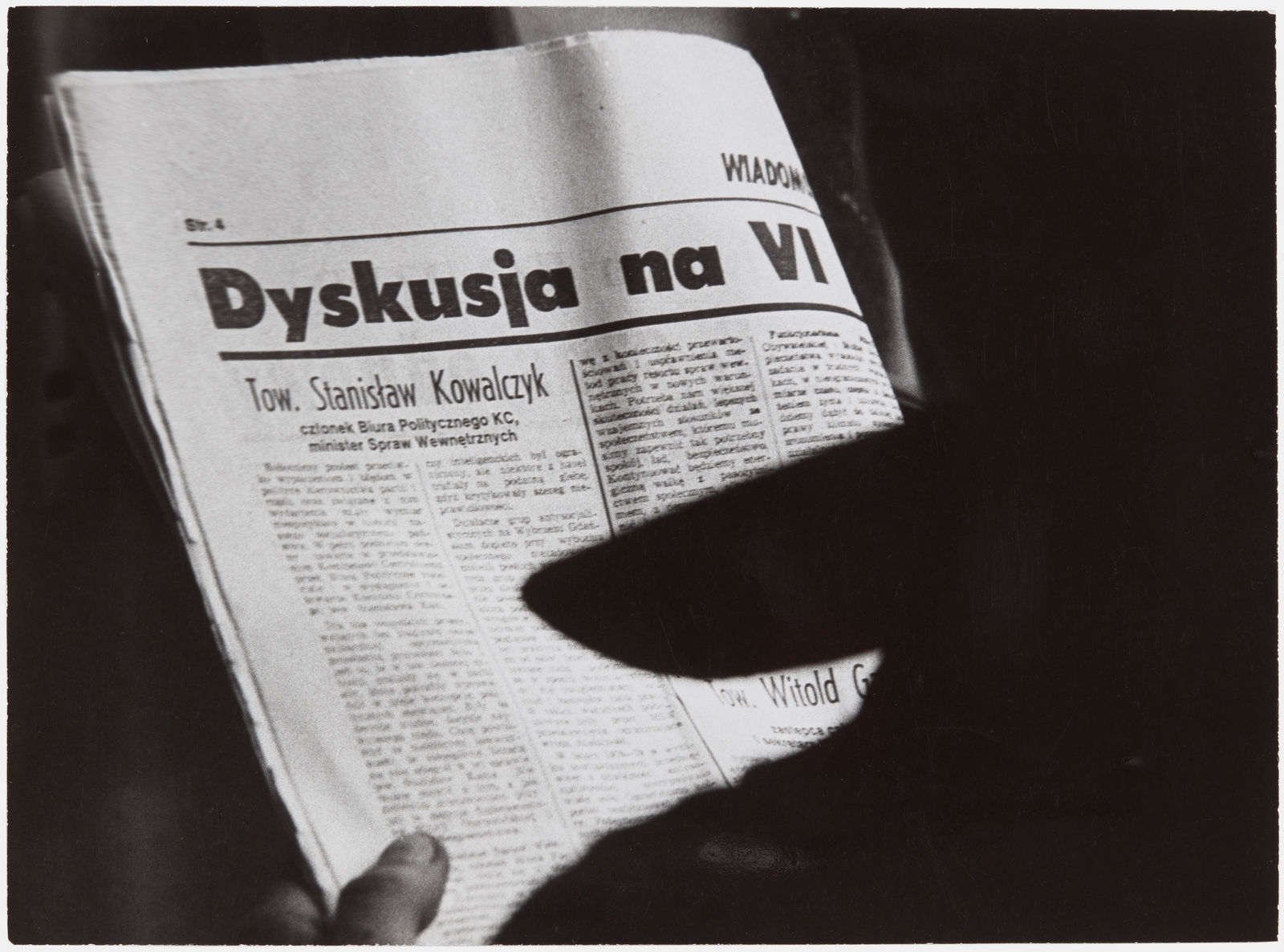

Zygmunt Rytka, ‘Bluff’, 1975-1979

© Fundacja Sztuki Współczesnej In Situ

If, in his early works from the 1970s, Rytka is analytical and seeking to be contemporary, aspiring towards a post-conceptual, cool approach to the world, then at the end of the decade, in his work on Bluff, among others, he is as ironic as Zdzisław Sosnowski. And then, a moment later, during martial law, he becomes as reflective as Roman Opałka and Władysław Strzemiński rolled into one. This does not prevent him from creating work in the punk and off-art aesthetic from the Łódź milieu of Strych and Kultura Zrzuty, or producing coloured portraits of friends and acquaintances in Private Collection. And it does not stop him from competing with the minimalism of Koji Kamoji in the 1990s. Which is the real Rytka? Which one should we trust, which should act as our guide to lead us through this rich, but incoherent oeuvre? As Jerzy Busza writes, “Zygmunt Rytka sought certain values, encountering relativism everywhere, and thus depriving us of the actual, reliable support upon which we could organize our ideas. And it seems that he has found that sacred value in the silence of stones, in the silence of everlasting nature”.[12]

Rytka seemed to be of the same opinion as Busza. This is clearly demonstrated in the covers of his catalogues, the works featured in his exhibitions, and the photographs and texts he selected for photocopying and printing. Rytka’s preference was to exhibit stones and his works using stones from the 1980s. These constituted the core of his oeuvre. On the other hand, as the years pass by, Jerzy Busza’s opinion needs updating: when he writes, for example, of Bluff that the artist “loses the contest” with Sosnowski’s Goalkeeper. Is this really “losing”? Sosnowski is known only for his Goalkeeper, while for Rytka Bluff was just one of many episodes.

And this episode arouses enthusiasm among critics exploring the foundations of modernity in the 1970s. There is no point in trying to compare Rytka’s numbered stones with Opałka’s paintings, or his spatial objects with Kamoji’s installations. And there is one more thing to say about Busza’s essay: that it poses a question every critic researching Rytka’s work is confronted with. What is most important in the artist’s oeuvre? As Busza’s essay shows, the answer should perhaps take the form of a cognitively creative criticism which re-evaluates existing interpretations of Rytka’s oeuvre. It might be the case that Rytka is more interesting and intermedial than, for example, Stefan Wojnecki. Does he not “win” over Józef Robakowski, as far as humour and distanced irony are concerned? Is it not the case that his dialogue with nature is more developed and more interesting than that of Tatiana Czekalska and Leszek Golec? Is the self-reflection presented by Rytka not more profound than that of Andrzej Lachowicz and Natalia LL? Is his spirituality not more present and authentic than that of Paweł Kwiek? Are his videos not better than those made by the Film Form Workshop and others?

Zygmunt Rytka, ‘To Whom Does the Cosmos Belong?’, exhibition view, Krakow Photomonth press materials, photo: Kamil A. Krajewski / www.kamilkrajewski.com

Certainly, the multifaceted nature of Rytka’s activities means that we must select the most important works and define the most important directions. There is something for everyone here. As far as I am concerned, the photographs from the Some Meetings cycle, later developed in the Private Collection cycle, are fundamental. Sociology in Polish conceptual reflection has never been a very strong presence, and Rytka shows us which way reflection on the neo-avant-garde could have gone. It is the key milieu – as Łukasz Ronduda described in his book – for Polish art around the turn of the 21st century. It is a pity that Ronduda ignored Rytka, rather than following Busza in seeing him as an artist important for the breakthrough era and, more broadly, the last quarter of the 20th century. Perhaps this type of omission is partly due to the artist’s attitude of hesitancy, and even an increasing underestimation of his own oeuvre towards the end of his life. One example is the case of his documentation of artistic life: S.M. and Private Collection were perhaps unintended as works of art, but they are wonderful – as is his documentation of the Polish art scene and his performance art, both of which are of significance for the Polish and international artworld alike.

An attempt at systematization

The same problem remains as far as the choice of Rytka’s best works and the inevitable process of evaluation and hierarchization are concerned, because we do not have a full catalogue of his works, or even his exhibitions and texts. Future detailed studies should therefore focus on specific areas in which Rytka was active, as well as shedding new light on already known works. One should bear in mind that the artist himself did not make life any easier for critics, curators and researchers. Not only did he not care about the systematization of his oeuvre and its development, but he more or less consciously agreed to dispersion, and even allowed all sorts of genuine errors to be made by art institutions working with him.

He also removed from his oeuvre those elements he considered to be less interesting at any given moment. Therefore, the widely known works featuring the Fiat 126p did not actually see the light of day in the 1980s and ‘90s, and were only discovered in the early part of the 21st century, when Łukasz Ronduda initiated the interest in and peculiar fashion for the neo-avant-garde of the 1970s.[13] Unlike Józef Robakowski, who documented all of his works, even the least significant ones, Rytka omitted entire sequences from his oeuvre, such as the cycles with ants from the 1990s. At the end of his life, they seemed to have lost any particular meaning for him. One should read Busza’s essay to learn about the number of artistic facts, exhibitions and works from his early period which have not been discussed since then.

Zygmunt Rytka, ‘To Whom Does the Cosmos Belong?’, exhibition view, Krakow Photomonth press materials, photo: Kamil A. Krajewski / www.kamilkrajewski.com

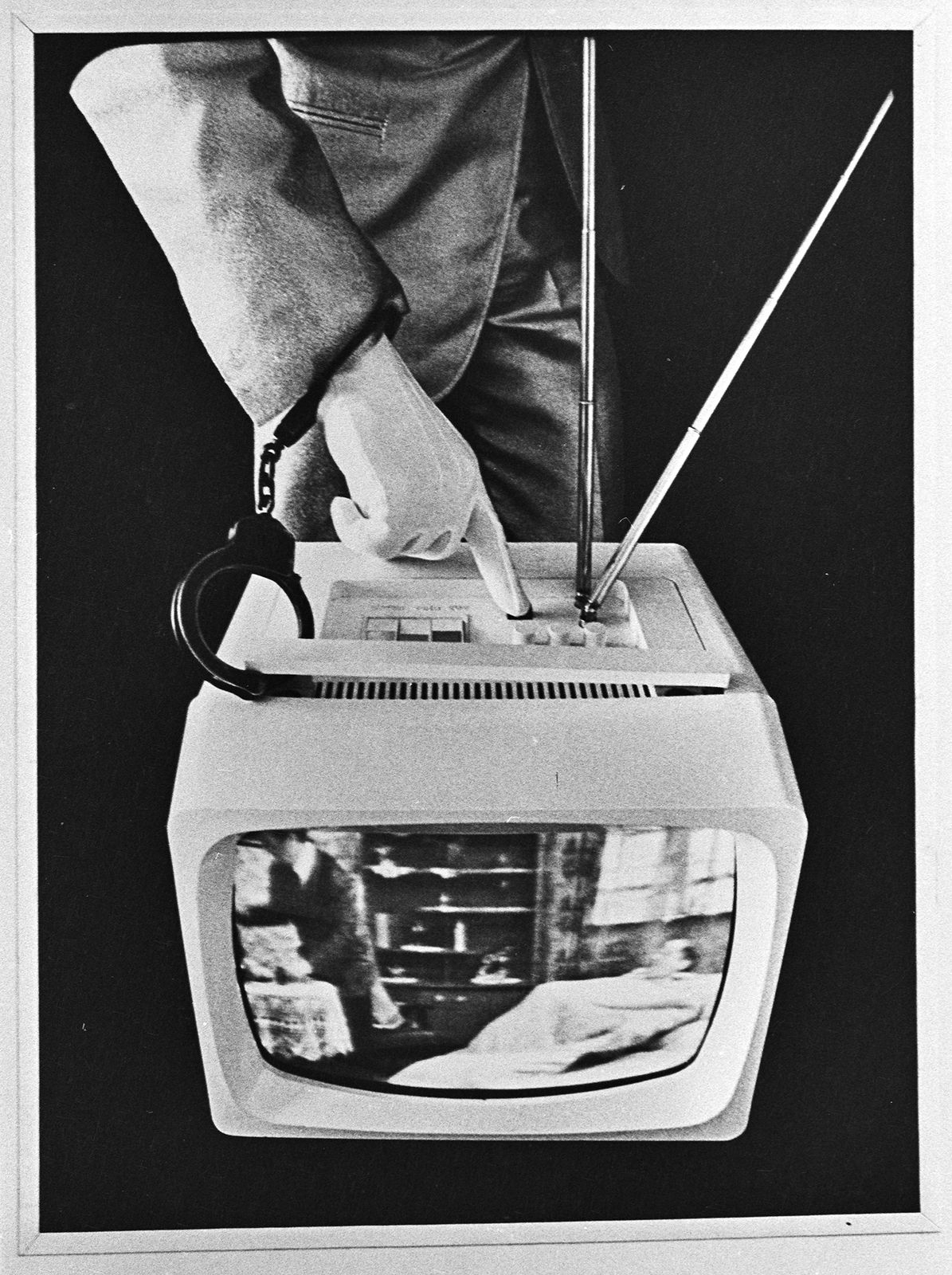

In An Introduction to Objective Photography (1976–1978), Busza writes about the holograms and TV recordings of the early 1980s.[14] Rytka did not treat photographs and films made at the request of his friends as works of art. He also considered the works from S.M. Catalogue as secondary, and did not sign or annotate them in any way. A generous man, he would give them away. At the end of his life, this kind of behaviour irritated the galleries and collectors working with the artist. A telling example of Rytka’s attitude towards art institutions is the dispute over the catalogue accompanying his exhibition at Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź curated by Krzysztof Jurecki.[15] Despite his strong and friendly relationship with Mała Gallery and Marek Grygiel, Rytka accepted the omission of this gallery in Jurecki’s publication. When asked directly about it, he replied that “he was not interested in art politics”.[16] Source materials such as the Łódź catalogue are therefore full of errors and misrepresentations, including the artist’s date of birth. This means that each catalogue, essay, exhibition list and publication concerning Zygmunt Rytka would require critical verification by art historians.

At this point, one should attempt to begin to compile even a basic chronology and classification of Zygmunt Rytka’s oeuvre. This should be divided into his early, mature and late periods. The early period might begin with his debut in 1972 and end with the imposition of martial law in December 1981, culminating in S.M Catalogue. The mature stage takes in the 1980s, with his most important cycle, Continual Infinity. The exhibition with the same title organized at Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź in 2000 concluded this period. The last decades of his life were overshadowed by his struggle with incurable illness. He participated in group exhibitions and presented his work at solo shows, but his active life was severely limited. This was also an important period, as Rytka lost nothing of his sensitivity and his intellect became even more acute. At this stage in his life, he clearly defined what was most important in his art. The classification of Rytka’s oeuvre needs to be seen from the perspective of place as well as time. For Rytka, particular places (Bukowina Tatrzańska, Białka River) and social circles (associated with Remont Gallery and Mała Gallery in Warsaw, Labirynt Gallery in Lublin, Strych in Łódź, Wschodnia Gallery, Exchange Gallery and FF Gallery) are of equal importance. His theatres, his collectors and his places were all constituents of his world. Towards the end of his life, Rytek stopped travelling, but he had many visitors in Podkowa Leśna, and then in Sokołowsko. Certainly the collectors who supported him and later became his friends – Wojciech Jędrzejewski, Dariusz Bieńkowski and Tomasz Niewiadomski amongst others – played an increasing role in his life.

Zygmunt Rytka, working on the series ‘Ciągłość nieskończoności’ Jurgów 1988, author unknown © Fundacja Sztuki Współczesnej In Situ

In terms of the specifics of Rytka’s oeuvre, various research tools can be applied to support and guide possible interpretations, starting with those provided by Krzysztof Jurecki, Piotr Krajewski, Ryszard W. Kluszczyński and others who emphasized its intermedial character. Unlike this aspect of the work, there has not yet been discussion of his philosophical themes, the existential and spiritual dimension of his art, or any post-anthropocenic intuitions. An exception might be some general references, such as those in Joanna Szczepanik’s text published in Obieg.[17]

The fact that Rytka was not included in Ronduda’s book also results in missing research on the artist’s role in Polish neo-avant-garde art. In his curatorial essay accompanying the exhibition at Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź, Krzysztof Jurecki attempted to position Rytka in a broader international context. This important attempt needs to be verified and brought up to date in relation to Rytka’s contribution to contemporary art, both in Poland and on the international scene. The dialectic proposed by Busza encourages us to look at the contrasting emotions or moods accompanying not only the creation but also the reception of Rytka’s works. Humorous and mocking actions like Bluff or the nonsensical behaviour characteristic of people associated with Strych in Łódź stand in contrast to more serious, existential and reflective actions. In looking at Rytka’s oeuvre, we become aware that man and his physical manifestation become less and less visible. In the photo of him standing in the rapidly flowing water of the Białka River holding stones in both hands, it seems that the current is about to carry him away, but he is still there, just for a moment. Or maybe he has already been carried away by time and the Białka River? Only fleeting memories, film cassettes, a pile of photographs and stones remain. This is the continual infinity explored by Rytka, revealed to us in the form of discontinued finiteness.

This text first appeared in an extended version in a publication accompanying Zygmunt Rytka’s exhibition To Whom Does the Cosmos Belong?, Krakow Photomonth 2020.

[1] Zygmunt Rytka, Ciągłość nieskończoności, ed. E. Fuchs, Łódź 2000.

[2] Zygmunt Rytka, Ciągłość nieskończoności, Muzeum Sztuki w Łodzi, 3.10.–19.11.2000, curator: Krzysztof Jurecki.

[3] Zygmunt Rytka, Moje formy zapisu, Warszawa 2018.

[4] Zygmunt Rytka, Moje miejsce, Warszawa 2008.

[5] A. M. Leśniewska, “Pomiędzy… Z Zygmuntem Rytką rozmawia Anna Maria Leśniewska, Podkowa Leśna, 16 stycznia 2000 roku”, in: Zygmunt Rytka, Moje formy zapisu, op. cit., pp. 20-128.

[6] K. Wojciechowski, untitled in: Fototapeta, fototapeta.art.ok/2001/rytkakatalog.php, access: 1.09.2019.

[7] M. Grygiel, “Moje miejsce”, in: Zygmunt Rytka. Moje miejsce, op. cit., p. 18.

[8] Cf. Zygmunt Rytka, Moje miejsce, op. cit. pp. 8-11.

[9] A. M. Leśniewska, Pomiędzy…, op. cit., p. 128.

[10] J. Busza, Wobec fotografów, Warszawa 1989, pp. 153–160.

[11] Ibidem, p. 159.

[12] Ibidem, p. 159.

[13] Ł. Ronduda, Sztuka polska lat 70. Awangarda, publication concept by P. Ukłański, Jelenia Góra–Warszawa, 2009.

[14] J. Busza, op. cit., p. 155.

[15] M. Grygiel, Nierzetelne informacje w katalogu and K. Jurecki, Odpowiedź na tekst Marka Grygla z Fototapety, Fototapeta, fototapeta.art.pl/2001/rytkakatalog.php [access: 1.09.2019].

[16] A. Mazur, Wynik doboru naturalnego. Z Zygmuntem Rytką rozmowa o Małej Galerii i nie tylko…, Fototapeta, fototapeta.art.pl/2003/zrt.php [access: 1.09.2019].

[17] J. Szczepanik, “Czasoprzestrzenne projekty Zygmunta Rytki”, Obieg, https://archiwum-obig-ujazdowski.pl/prezentacje/ [access: 1.09.2019].

Imprint

| Artist | Zygmunt Rytka |

| Exhibition | To Whom Does the Cosmos Belong? |

| Place / venue | former Cracovia Hotel, Cracow |

| Dates | 26 June – 26 July 2020 |

| Curated by | Karol Hordziej |

| Website | www.photomonth.com |

| Index | Adam Mazur Karol Hordziej Krakow Photomonth Zygmunt Rytka |