Performing the Fringe is an artistic and curatorial research process that explores three different contexts in the rural–urban fringe areas of the cities of Stockholm, Pori and Vilnius. It started with inviting artists to undertake research hikes during spring and summer 2019, experiencing three distinct environments that have now materialized into artistic commissions. Exhibition Performing the Fringe at Konsthall C is the first iteration in the series of presentations of those artistic commissions.

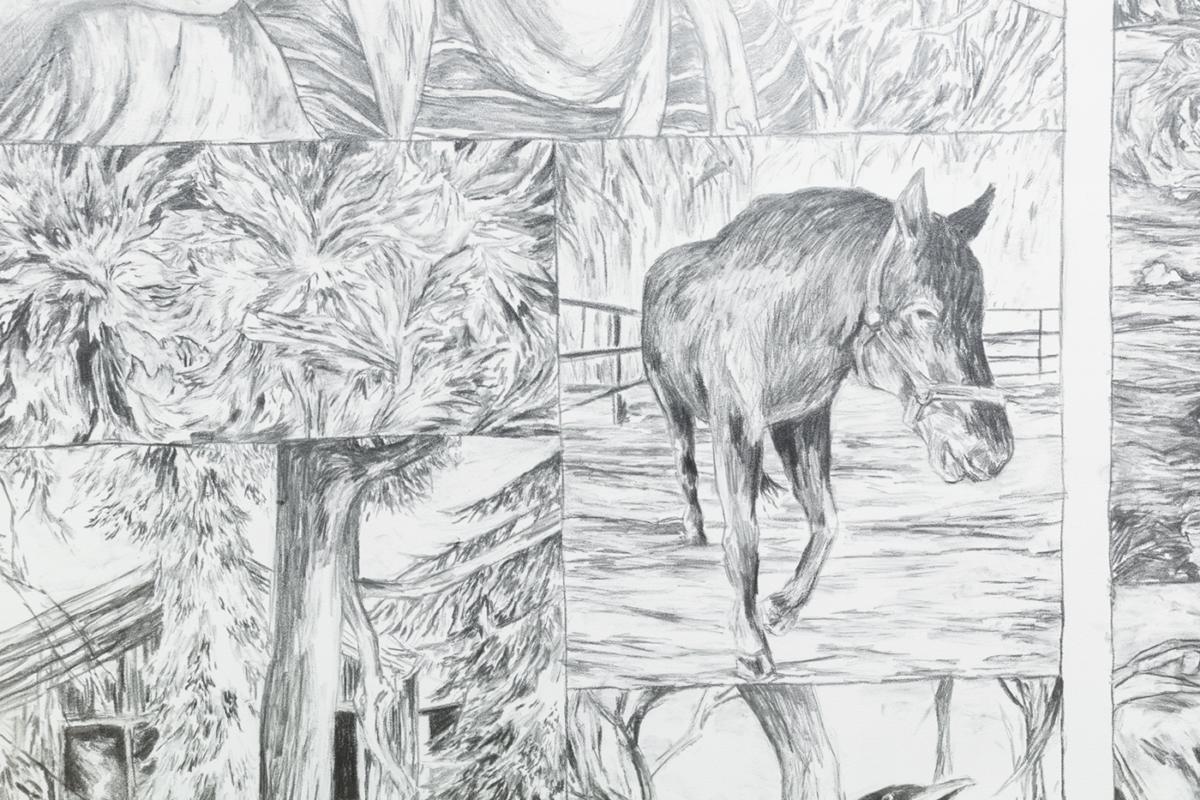

Within these contexts, hiking unfolded as a common activity that combines walking, observation, inquiry, talking, listening, and engaging with regional specificities. Collaborating with guides on site and visiting particular locations, hiking-practice operated as a tool for research and understanding, seeking to change perceptions of the terrains between city and rural areas.

During the last three decades, the harsh neoliberalisation of economies has impacted Nordic and Baltic societies across different registers and timescales. Those developments have manifested changing relationships between the commons and privately owned lands, resulting in ecological and economical abuse of the environment, and the application of capitalist logics to urban-rural areas. Processes of ongoing natural resource overconsumption coupled with growing income gaps have also caused both melancholia and the incapacity to act collectively in productive ways. It has also crumbled beliefs in democratic decision-making, enabling populist voices to gain popularity. The situation demands speculating about new kinds of agencies that could affect understandings of cohabitation; urban and rural spaces; and who and what could be considered active agents within a region’s societal, political and economic level, as well as within the broader cultural field.

There is a certain economic activity described by Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing as “pericapitalist” that exists in the geographic or social periphery of the capitalist gaze; it is both in between, or almost, capitalist. Sometimes inhabiting suburbs or unused spaces in the city centre, it encourages different economic models to meet. There seems to be more and more grey-zones that can be called pericapitalist, always shifting, and thus having the potential to reimagine the current system. The areas of pericapitalist activity both constantly contaminate and operate as sets for negotiations and struggles that are developing and reproducing hybrid zones, where non-capitalist change could prosper. Small Nordic and Baltic cities—and their traditionally active economic and social use of pericapitalsit fringe areas between the city and non-city—can be seen as models for negotiations between the city/rural; human/non-human; and economic, social, and cultural agencies.

The project brings forward artistic practices as ways of exposing and materialising permacultural traditions, non-human histories, post-neoliberal urban activities, non-industrial food producing, allotment garden towns, and other small-scale economic and ecologic activities in the region. Also, it challenges the normalised divisions of function/non-function, human/non-human, built/empty, and productive/non-productive, to open up more hybrid, blurred, and merged notions about contemporary urban and rural spaces, and the agencies forming within them.

Excerpts and Notes from the Research for “Performing the Fringe”

The Right to Roam

The right to roam is a principle that allows everyone to travel the countryside. For example, you might forage, fish with a rod, and enjoy the recreational use of natural areas. The right to roam exists in different forms throughout the Nordic and Baltic countries, as well as Austria, the Czech Republic, Scotland, and Switzerland.

In Finland, you are free to:

- Move by walking, skiing and biking in natural areas

- Ride a horse without damaging the land

- Spend time and stay overnight temporarily

- Pick unprotected berries, mushrooms, and plants

- Use a boat, swim, and move on the ice

- Fish with a rod

There is no clear juridical historical narrative for the right to roam. Sparsely populated areas, a lack of suitable farming land, and large scale land ownership have affected how the right to roam has developed. For example, in Finland there is no single law that grants the right to roam, but a combination of more than 30 different laws that grant and restrict ways of acting in nature. In recent years, the right to roam has been contested within political debates related to the rights of foreign workers who come to pick berries for food companies in summer times.

(Jussi Koitela)

“Pericapitalist” economy

“Capitalism is a system for concentrating wealth, which makes possible new investments, which further concentrate wealth. This process is accumulation. Classic models take us to the factory: factory owners concentrate wealth by paying workers less than the value of the goods that the workers produce each day. Owners “accumulate” investment assets from this extra value.

Even in factories, however, there are other elements of accumulation. In the nineteenth century, when capitalism first became an object of inquiry, raw materials were imagined as an infinite bequest from Nature to Man. Raw materials can no longer be taken for granted. In our food procurement system, for example, capitalists exploit ecologies not only by reshaping them but also by taking advantage of their capacities. Even in industrial farms, farmers depend on life processes outside of their control, such as photosynthesis and animal digestion. In capitalist farms, living things made within ecological processes are co-opted for concentration of wealth. This is what I shall call “salvage,” that is, taking advantage of value produced without capitalist control. Many capitalist raw materials (consider coal and oil) came into existence long before capitalism. Capitalists also cannot produce human life, the prerequisite of labor. “Salvage accumulation” is the process through which lead firms amass capital without controlling the conditions under which commodities are produced. Salvage is not an ornament on ordinary capitalist processes; it is a feature of how capitalism works.

Sites for salvage are simultaneously inside and outside capitalism; I call them “pericapitalis”. All kinds of goods and services produced by pericapitalist activities, human and nonhuman, are salvaged for capitalist accumulation. If a peasant family produces a crop that enters capitalist food chains, capital accumulation is possible through salvaging the value created in peasant farming. Now that global supply chains have come to characterize world capitalism, we see this process everywhere. “Supply chains” are commodity chains that translate value to the benefit of dominant firms; translation between noncapitalist and capitalist value systems is what they do.

[..] Pericapitalist economic forms can be sites for rethinking the unquestioned authority of capitalism in our lives. At the very least, diversity offers a chance for multiple ways forward-not just one”

(Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins, Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2015)

Posthuman Economy

One of the main thought processes that has been shaping the Performing the Fringe project is imagining what a posthuman economy could be like. This has been more like a framework that allows other questions to arise outside of a research framework that demands concrete answers. So how would a posthuman economy work? What kind of value would it produce, and for whom? Is it possible to decentralise human agencies from processes that consider what is valuable and useful? Is there value outside of human imagination?

Research

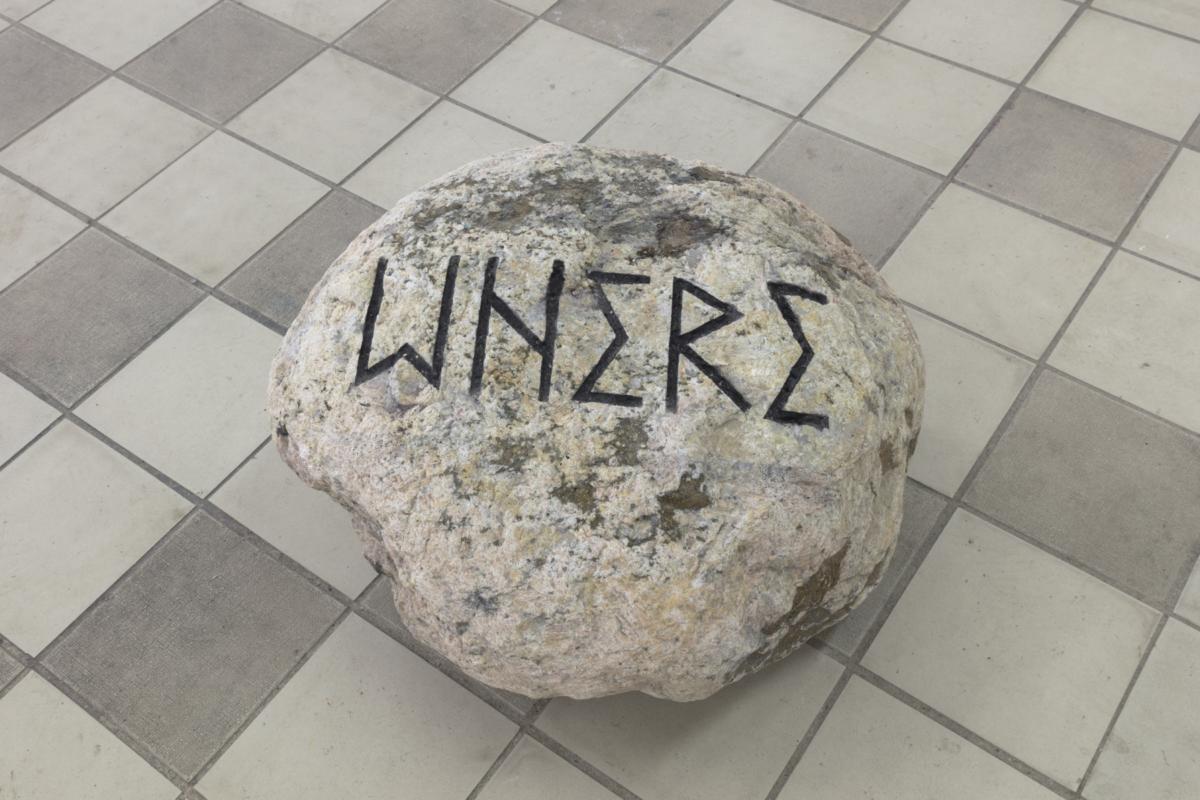

Embodied collaborative research in the form of hiking has for us been a way to situate ourselves (artists, curators, collaborators, our bodyminds) within the environments and contexts that the project is interested in. It offers a starting point for non-extractive research and knowledge production, and is an alternative for a human subject and body that wanders in the world, and makes “sense” of environments to accumulate gain and profit, to extract the value from the ground, from stones, and plants… and turn this value into infrastructures and other vessels of capital.

Collaborative and situated embodiment within a context that is understood as an entanglement of natural, cultural, human and non-human aspects and agencies forms part of a research methodology that offers the first steps for imaging what non-extractive research and knowledge production could and should be. In order to find new ways of understanding the future of democratic urban, rural, and public space, we need knowledge creation that acknowledges a much wider spread of agencies that contribute to its production.

Value

Similarly, value creation is a collaborative effort. As environmental historian and historical geographer Jason W. Moore explains, value emerges in the web of life. Value is not only created by humans arranging and turning land, stones, forests, plants, animals, and minerals… into urban space infrastructures where further speculation can take place and capital can move into new frontiers. Human and non-human agencies are co-creators of value in the shared web of life, so this lens is useful in order to comprehend a more just future in which people think who and what is benefitting from the commonly created value.

Urban/rural…

… and self/others, natural/cultural and other differences and dichotomies that constitute the web of life need to be re-thought and re-practiced. Within the “posthuman economy”, co-production of value cannot simply be about turning “nature” into “culture” by cultivating natural areas to human-build infrastructures, or by human-subject turning natural “others” into objects of abuse. What is needed is an imaginary that emphasises entanglements and dependencies, instead of differences and autonomous actors.

(Jussi Koitela)

Post-Soviet Baltic context: from collective farming to privatization of land

The comparison that the collective embodied research experience of the project Performing the Fringe provided on the Nordic and Baltic countries and their relationship to land, nature, urban and rural development processes, as well as human-non-human relationships, demands some leaps in the history.

During the time of the Soviet Union, all three Baltic countries underwent a different economic organization based on state control of the means of production, centralized planning, industrial manufacturing and collective farming. The kolkhoz (коллективное хозяйство – kollektivnoye khozaystvo, or collective ownership) was both a symptom and a powerful symbol of that change in small towns and rural communities. Collective farms or kolkhozes were important components of the farm sector that began to emerge in the Soviet Union soon after the October Revolution of 1917 as an antithesis both to the feudal structure of serfdom and aristocratic landlords and to individual or family farming.

Massive collectivization set in across the Baltic countries after the Second World War. With collectivization, the Latvian countryside underwent changes for the second time within twenty years. In 1920, the new Latvian government expropriated manor properties and sold them to landless farmers. In 1940, the occupying powers confiscated land and gave it to farmers who still had no land. In addition, the Soviets abolished private property. In 1920, the state nationalized, or confiscated, manors, but created a new landowning class. In 1940, all property was nationalized, and people were forced to set up kolkhozes. A utopian socialist idea, followed by an incredibly inefficient realization.

“In the 1990s following the breakdown of the socialist state and proceeding regression toward capitalism that was prescribed by neoliberal economists as shock-therapy for economically undeveloped and politically unstable countries…the concept of collective emancipation was stripped down and people were left alone to find their ways to survive rapid privatizations of the state-owned enterprises, collapses of the institutional system, commodification of public services, deregulated market competition, and glorified globalization that was promising a speed lane to the instant personal wealth. Following shock-therapy, the post socialist city has been undergoing a radical, paradigmatic reversal: from a space shaped by the socialist state as a focus of public political interest on human wellbeing to a space shaped by unleashed private economic interests; and from a planned city to a city where no urbanistic concepts are required…. A new urban layer created by the scattered singular developments including office buildings, shopping malls, hotels, warehouses, and housing compounds started to dominate over time-worn surroundings.” (Ivan Kućina, Commoning of the Uncommonness: Developing Urban Commons in Post Socialist City, 2016)

(Inga Lāce)

Eco-nationalism

“Once the catalyst for independence movements in the late Soviet period, environmentalism in Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania has become greatly influenced by the processes of social, political and economic transition. With the rise of the schizophrenic response of toleration and repression to liberal reform in an authoritarian Soviet Union, activists in the three Baltic states set out to use the environment as a specific representation for what the Soviet occupation had done to the Baltic republics in general. Each of the Baltic republics had their own environmental issues with which to deal. In Estonia, environmentalists focussed on on the ecological damage from the phosphate and oil-shale mining in the north of the country. In Latvia, the aim was to prevent another hydroelectric dam on the Daugava, a central river splitting the country in two. Finally in Lithuania, environmentalists set out to campaign for the closure of an ageing nuclear power plant and prevent the construction of another plant. Each one of these movements to protect the environment was a move against ecological degradation, while at the same time a challenge against the central planning of the Soviet economy and overall Baltic inclusion in the Soviet Union. In the Baltic republics, the environmental movements and independence movements were inextricably linked, to the extent that Jane Dawson refers to a single movement she calls eco-nationalism.”

(David J. Galbreath, From Phosphate Springs to ‘Nordstream’: Contemporary Environmentalism in the Baltic States, Journal of Baltic Studies, Volume 40, Issue 3, 2009)

Hikes before our hikes: Workshop for the Restoration of Unfelt Feelings and Man in the Living Environment

The artist, trained architect, and musician Hardijs Lediņš (1955–2004) and artist and poet Juris Boiko (1954–2002) were the driving force of the interdisciplinary group Workshop for the Restoration of Unfelt Feelings (NSRD), which did unconventional gatherings, concerts, happenings and performances in Latvia beginning in the 1980s. During the Soviet period, the Latvian art scene was largely disconnected from art processes in Europe; however, Lediņš and Boiko were among the few who worked beyond the institutional system. Their work included avant-garde and underground music, visual arts, absurdist literature and poetry, theories on architecture, performances, and installations. These endeavours opened up a completely new means of expression in Latvia at the time and destroyed the boundaries between artistic disciplines.

Starting in 1980, NSRD went on an annual hike from their homes in the centre of Riga to the suburban area of Bolderāja. The hike included performances during the walking and was documented, initially with images and eventually with video and music. Each year more artists were invited to join.

Another example of their interest in the urban environment is reflected in their first film, Cilvēks Dzīvojamā Vidē (Man In A Living Environment), which was released in 1986. It documented Soviet apartment blocks and their effects on inhabitants, including music, critical voice-over commentary, and footage of NSRD members performing during the walk.

(Inga Lāce)

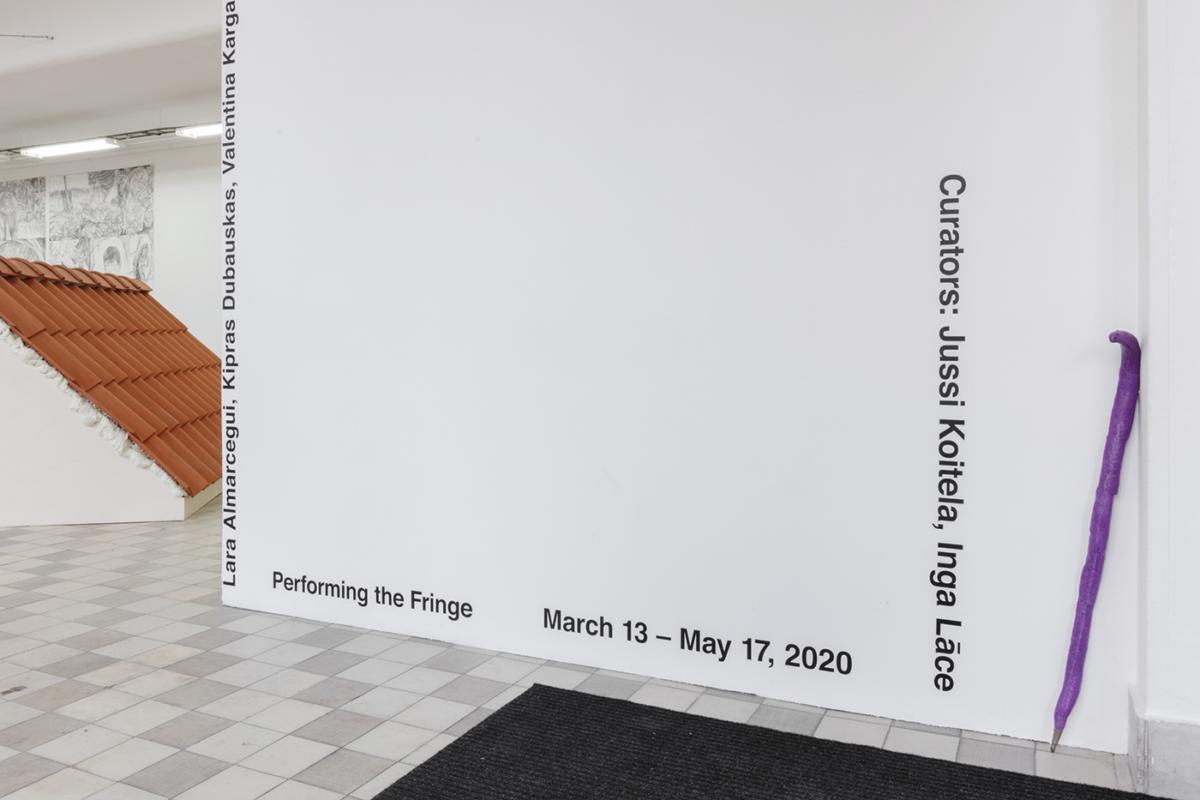

Imprint

| Artist | Lara Almarcegui, Kipras Dubauskas, Valentina Karga, Flo Kasearu, Michèle Matyn, Andrej Polukord, Asbjørn Skou, Urban Fauna Lab, Jon Benjamin Tallerås, Eero Yli-Vakkuri |

| Exhibition | Performing the Fringe |

| Place / venue | Konsthall C, Farsta |

| Dates | 13 March – 14 June 2020 |

| Curated by | Jussi Koitela, Inga Lāce |

| Website | www.konsthallc.se |

| Index | Andrej Polukord Asbjørn Skou Eero Yli-Vakkuri Flo Kasearu Inga Lāce Jon Benjamin Tallerås Jussi Koitela Kipras Dubauskas Lara Almarcegui Michèle Matyn Urban Fauna Lab Valentina Karga |