Ibrahim Mahama (1987, Tamale, Ghana) is no stranger to large-format exhibitions. You’ll find Documenta 14 in Athens and Kassel (2017) and three editions of the Venice Biennale (2015, 2019, 2023) in his dazzling portfolio, while his representation is managed by the prestigious White Cube gallery. Due to this, Mahama is sometimes slightly enviously called a star artist, and is perhaps most famous for the large-scale installations of jute sacks, stitched together and draped over buildings. Despite (or because of) his popularity, Mahama is tired. During our first meeting, I finish half of my meal in the time it takes him to list the destinations he’s travelling to in the coming months, and he tells me he feels his energy receding – “I’m not as young as I used to be”, he says light-heartedly. He works all over the world, but lives and is most at home between Accra, Kumasi, and Tamale, Ghana.

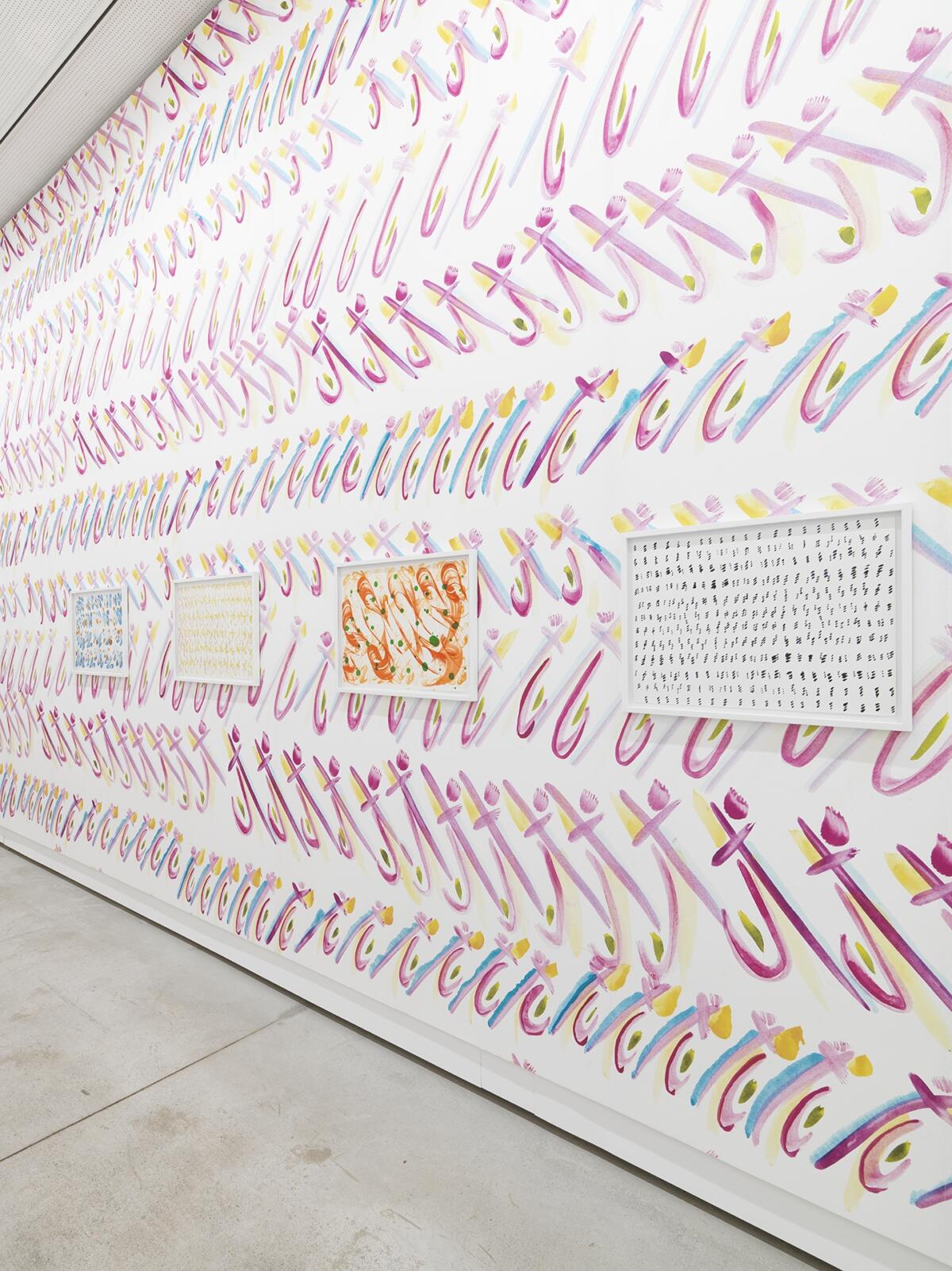

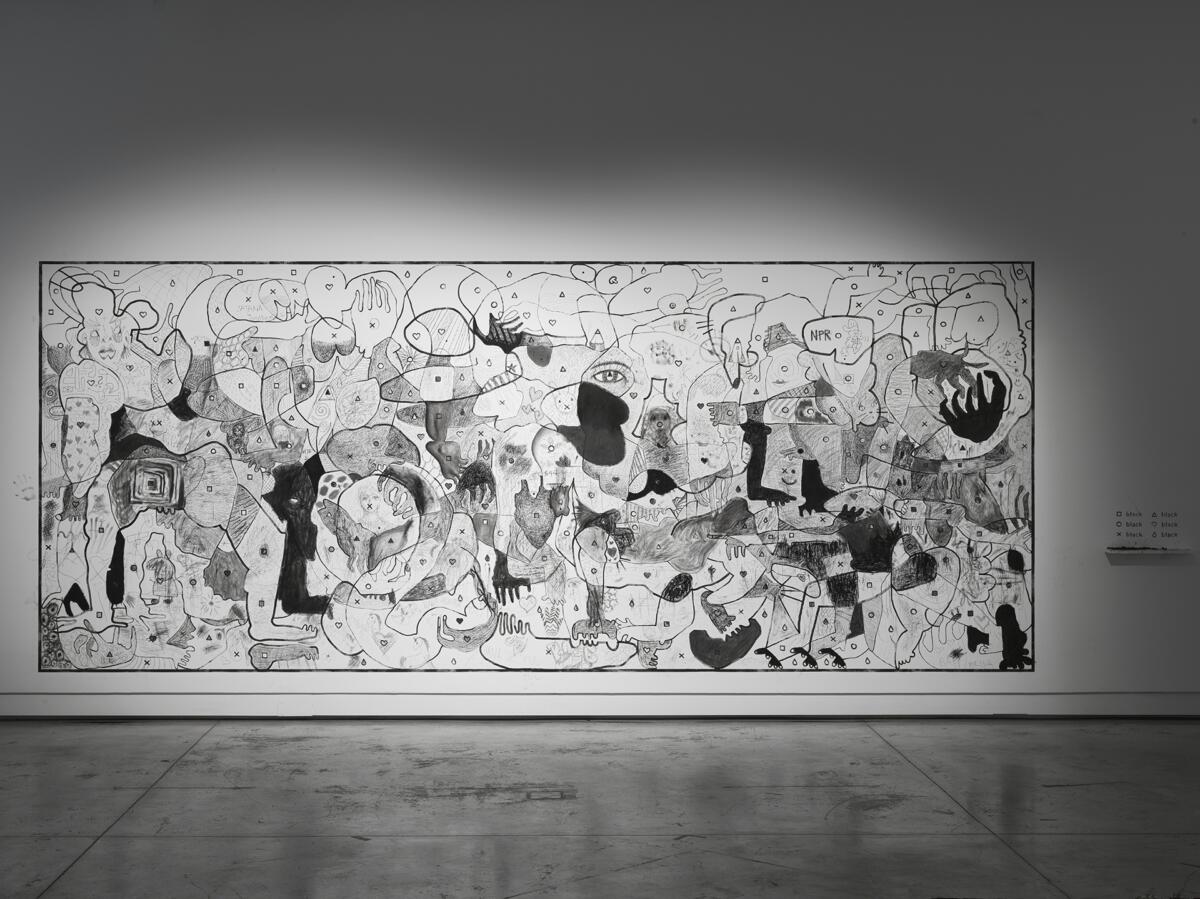

Recently, he took on the role of curating From the Void Came the Gifts of the Cosmos, the 35th Biennial of Graphic Arts in Ljubljana. It is structured around seven different venues, from main exhibitions in the International Centre of Graphic Arts and Cukrarna, to Švicarija, Plac, Krater, the Wednesday Group, and others, with six curators and curatorial collectives by Mahama’s side choosing the exhibited works. Over 55 artists and collectives presented their work at this year’s edition, where they decided to look back to the 1950s and 60s, to the beginnings of the biennial itself, analysing the emancipatory and utopian visions of both then-Yugoslavia, and Ghana under its first president Kwame Nkrumah, as well as their connection through the Non-Aligned Movement.

Even though we meet to discuss the biennial, Mahama’s eyes truly light up when he’s discussing his latest plans for Tamale, new energy entering into his gestures as he passionately begins to outline his future projects. He lived and studied in Ghana, at the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology in Kumasi, and is now dedicated to opening new educational institutions there – in 2019, he opened the artist-run project space Savannah Centre for Contemporary Art (SCCA) in Tamale, followed by the opening of a vast studio complex, Red Clay, in nearby Janna Kpeŋŋ in 2020. Most recently, Mahama opened a renovated silo, Nkrumah Volini, in Tamale (2021), where artistic interventions, performances and educational activities take place.

Mahama’s artistic and curatorial practice feels vibrant and necessary in Slovenia’s capital – it not only offers a unique perspective on the Non-Aligned Movement from a Ghanaian viewpoint but also considers the principles of community, emphasizing solidarity and care. The Graphic Biennial had, after all, historically been an institution that has exhibited Ghanaian (and other Non-Alinged countries) artists since the late fifties, in line with the Cultural Convention Yugoslavia signed with Ghana in 1961. Today’s resonance with the values found in socialist Yugoslavia, which manages to be both historic and contemporary, adds an intriguing layer to the theme.

In a time of ever-growing critiques of biennials, their extractivist operational frameworks and focus on instant visitor gratification, it’s easy to become cynical when considering the purpose of art and its far-reaching impact. We (or at least authorities who allocate the funds we work with) tend to expect art to deliver immediate results, akin to our on-demand online orders and streaming services. Yet, Mahama’s perspective challenges this notion, encouraging us to view art and its relationship with society from a broader perspective. Artistic endeavor, unlike our quick-fix expectations, doesn’t yield instant outcomes. Mahama’s approach shows that it can reach across time, culture and space – and while that might be immeasurable in its immediate form, it could have lasting consequence for a time and place removed from our own.

The following interview is the edited version of two conversations with Ibrahim Mahama in April and September, 2023, respectively. The Ljubljana Biennial of Graphic Arts is on view until January, 2024.

HČ: The title of this year’s biennial is From the void came gifts of the cosmos. Where does it come from?

IM: This is something that stems from a personal initiative. In Ghana, I often visit villages and communities, collecting objects that are becoming increasingly rare. Modernization has led people to favor new and beautiful items, much like the constant desire for the latest iPhone. However, I noticed that these remote areas rarely benefit from development projects. I began thinking about the significance of these remote places, where food is produced and traditional beliefs are upheld, yet are often excluded from the cosmopolitan experiences. It became apparent that to find original textiles and other artifacts, one must venture into these villages, where people treasure and preserve the old ways. When I’d collect these items, individuals would guide me to their rooms, where these treasures were stashed away, often beneath the bed or in a wardrobe. Initially, I had chosen the title From under the forgotten bed came the gifts of the cosmos.

I contemplated this in relation to the silos from the 1960s, built after Ghana’s independence by the country’s first president Kwame Nkrumah for the storing of food. They were built with engineers from Yugoslavia, Poland, the Soviet Union, different places in Africa, and later abandoned. The silo and the space under the bed shared a certain darkness, a void. It struck me that this void could serve as a portal for traveling back in time and revisiting past collaborations. It was like a new void, one that allowed us to reexamine these connections. Yet, as I pondered these matters, the conflict in Ukraine unfolded, introducing multiple troubling realities in global politics. The relationship between Russia and African countries, such as Nigeria, Burkina Faso, Mali, and South Africa, became increasingly complex. It raised questions about Western influence and interference, even in the natural world.

The EU’s central role in creating extreme debt in many global South countries, who were then compelled to supply raw materials, added to the complexity. Many nations questioned the effectiveness of this new colonial form, criticizing the decades of foreign aid that had not led to progress. There was a growing sentiment that self-reliance might hold the key to a different future on the world stage. The intersection of historical facts, imaginative thinking, and philosophical perspectives in politics became evident. Examining the world from an imaginative and philosophical standpoint could offer solutions to current problems, extending our responsibility beyond the present into the distant past and future. It’s a thought-provoking concept, especially when we consider applying these ideas artistically on a global scale.

In summary, this project is a reflection on the changing dynamics of global politics, exploring how the past, present, and future can be reshaped through imaginative and philosophical lenses, a compelling idea when considering the intersection of art and the broader world.

HČ: It appears your focus in this biennial is shifting from the International Centre of Graphic Arts (MGLC) into the city. Can you clarify how this transition will take place?

IM: To move away from a single exhibition space was my initial proposal for the biennial. I come from very Marxist training and wanted to share certain pedagogical approaches from my background, where we analyzed how capital influences art, both formally and politically. I wanted to discuss the artist’s choices in creating art, not just in the context of galleries, but as a political decision. Why choose option A or B, and what are the associated political implications? Museums often attract only the usual suspects, leaving out many others. Most [Western] art audiences go to museums and talk about art over their wine glasses. It’s absolute nonsense. I will sometimes go to openings just to see how people behave towards art, and observe that sense of pretence, of trying to be sophisticated, to understand everything. This raises questions about why certain groups engage with art while others don’t. Museums are claiming they can’t attract certain audiences, especially the less affluent – but why do they think that is? Why do they attract only the middle class and the rich? It means that fundamentally, there is a glitch in the system, a systemic issue that art can address. Architecture also plays a crucial role, and while I’m not a fan of white cube spaces (though am, ironically, represented by White Cube gallery), they served an ideological role in the 20th century and moved art away from the academy. At the same time, this was a disastrous century of pure extraction, with too many wars fought and too little learned from it (as seen over and over again today). Art should also consider its role in sustaining life and shaping future generations, breaking free from the cycle of endless wars and profiteering.

HČ: There is definitely a common denominator connecting the participating artists in the Graphic Biennial. Dealing with space seems to be a recurring theme, especially public space.

IM: The selection of artists and projects was a collaborative effort involving all the curators [Exit Frame Collective, Alicia Knock, Selom Koffi Kudjie, Inga Lace, Beya Othmani, and Patrick Nii Okanta Ankrah]. Alicia and Inga, both serving as the artistic directors for the Kaunas Biennial and Survival Kit in Riga, have been engaged in exploring the theme of the Non-Aligned Movement, collaborating with artists to create work intended for public spaces. Exit Frame Collective has played a pivotal role, bridging artists from various continents and facilitating initiatives like workshops and critical discourse programs. They’ve also been instrumental in helping artists realize their projects. Patrick Nii Okanta and Selom Koffi Kudjie, both artists themselves, primarily focus on mentoring and collaborating with emerging artists, which aligns with our interest in the student community here. Additionally, Beya Othmani brings a wealth of experience in working with artists from North Africa and other parts of the world, particularly in the realm of public art projects.

So it was somehow clear to me that these curators approached their work from a political position. While some curators lean towards visual and aesthetic aspects, seeking spectacle, these curators showed a strong interest in the form, materiality, and the production system. When they were invited to work on this theme, they immediately began seeking artists locally and elsewhere who could expand upon the topic. This expansion was a central objective: to move beyond the established confines of the biennial, breaking out of traditional spaces and exploring new possibilities. To some extent, we faced challenges, as we couldn’t secure all the spaces we had hoped for, particularly for site-specific works. However, this experience served as a valuable learning opportunity, not a final destination. It motivates me to return, as I am eager to witness the activation of these spaces in the future. Maybe through independent projects and collaborations with others, we can achieve what we couldn’t this time.

HČ: The biennial is presenting mostly contemporary works in all sorts of mediums, but also historical graphic prints, like those of Malle Leis (1971–1973) or Aldona Skirutyte (1966). How did you choose the artists while oscillating between the historical and contemporary perspectives?

IM: I based my selection on the theme, some projects I chose already and the students’ works. I also invited curators from Latvia, France, Tunisia, and Ghana, as well as a collective of artists. They have been developing these ideas for some time. The Exit Frame Collective will primarily handle pedagogical projects within the exhibition. My goal was to allow local students to propose works for the exhibition since many biennials focus on superstar artists and overlook the potential of collaborating with students and art schools, which are centers of creative production. It’s essential to include the diverse range of ideas that emerge during the formative stages of artists’ careers. Some of their ideas might not work or be immature, or the projects don’t finish on time. But at least it’s important to include that within the grand narrative of, let’s say, what exists within the contemporary.

HČ: I think it’s great that you’re incorporating younger artists, including students, as they often face limited opportunities in Slovenian public institutions. There is a hesitation among curators and museum directors to embrace younger artists, especially students. How will they be integrated with other artists in the exhibition?

IM: Students were commissioned to create new work, both from Slovenia and Ghana, which is displayed alongside historical works. We are also including some historical works on loan in the exhibition. The concept is to involve students who may not physically showcase their work but contribute through their labor to the exhibition. They can collaborate with established artists to create their work within the show. Joint projects between artists and students are possible.

Reflecting on my personal experience, I, too, was a student when I was invited to exhibit at the Venice Biennial. I was invited in 2017 over Facebook Messenger. At first, I didn’t believe the invitation, thinking it was a scam. After some time, I sent my portfolio, and to my surprise, I received an official invitation. And it was shocking because at the university that I had studied in prior to that, the professors and the program were very conservative. They had gone through a lot of transformation themselves to make this new faculty that would inspire artists to think about artistic production differently. Most students in the school didn’t even know that Venice existed, and suddenly, one of us was going to exhibit there. I have since exhibited in Venice multiple times and am now participating in the upcoming Architecture Biennial in Chicago. It’s a testament to the importance of providing opportunities for dedicated students, despite the existence of some who may lack motivation.

HČ: There are also some who won’t continue working in art.

IM: Exactly. Even if some students don’t pursue their ideas further, it’s valuable to explore them during their studies. However, you can often discern those who are only looking for shortcuts from their work. On the other hand, when you come across the work of certain artists or students, you can see the potential in their ideas, even if they seem impractical. These ideas hold promise for the meaning of art and are worth trying, even if they don’t succeed in the short term. What matters is the proposal’s potential, even if it’s based on utopian ideals. Let’s give it a shot.

HČ: How do you engage the community in your work? Do you often draw on your experiences from projects in Ghana?

IM: Yes, I collaborate with a diverse community of people in Ghana, and we’ve been working together for years. They have assisted me in collecting archives and creating new ones, among other tasks. Each of us plays a specific role. My responsibility is to use the capital generated from my work [abroad] and to be responsible in how I exercise my rights and freedoms. In turn, they have the right to be generous and collaborate with me, creating additional opportunities. Within this community, we’ve been constructing a greenhouse that also incorporates a train. We have residency spaces, an archaeological museum, a parliament, and more.

I’m currently involved in various projects in Ghana, and I’m particularly excited about the upcoming phases. I’ve acquired old trains, which I’m transforming into residencies, music studios, and classrooms. My city hasn’t had a railway line for over a century, and I purchased decommissioned trains from the South. They were still functional; the government simply wanted to retire them. I transported these trains to the North, where I’m now working on a new building that will house a school and more. The unique concept is that a railway line will pass through the architecture, entering the building and then exiting it. People can sit in the train, which will travel through the museum, with a part of the train serving as a classroom. This allows students to study, for example, mathematics while experiencing artworks and other educational spaces within the train.

We’ve also acquired several decommissioned planes, some of which were used historically and their unique technologies mark different eras. I found it intriguing to expand the conversation, especially since children are highly fascinated by these aircraft. What would happen if they could occupy this historic void? I decided to remove the seats from the plane’s interior and transform it into a classroom where we teach coding and various subjects. Just imagine the excitement this generates among the kids. For me, it’s an exploration of the imaginative possibilities. This endeavor provides an opportunity to involve children in the process of transportation, allowing them to engage with these objects within the space.

So what does it mean to show this in its entirety? Exposing the process is a departure from the norm, as such endeavors are usually concealed and isolated from public view. Whether it’s creating a railway through a forest or building institutions, these hidden processes are typically known only to workers. However, our institution and environment magnify labor’s historical context, turning schoolchildren into time travelers who witness both the past and future unfolding. We involve them in tours during construction, as they will inherit these spaces. This departure from the usual practice raises the question: What if people could see how these spaces were built, including historical archives and memories? Would it change your perception of the institution if you witnessed its building?

HČ: Do you think that using solidarity as a focus of the exhibition is one of the ways to translate it into tangible actions?

IM: Yes, I guess so. There are many forms in which this can be done. One way is to establish a system that fosters a continuation of dialogue beyond the exhibition. I’ve been discussing with artists ways to extend their practice beyond the current context, such as in Ghana or other places. The question of ownership is also very important to me, because when you work in a capitalist world, you can lose a lot if you don’t own the means of production or the space where you operate. Ownership of spaces like the biennial locations is crucial. I intend to utilize resources from my work in museums, the capital they produce, to purchase forested areas and reactivate them, not just for humans but also for existing ecosystems.

Some discussions concerning solidarity are more critical now than ever. Artists are dealing with a loss of spaces. The creative lab Krater, for example, still working in precarious conditions, they could lose their place overnight. And yet, ideas conceived in a Ghanaian village might have relevance elsewhere. The challenge is dealing with the diverse needs and perspectives of artists from various backgrounds.

The biennial does have limitations, economically and otherwise. For us, the major goal is not about visibility, although some artists are showing their work for the first time. We aim to establish cultural and political dialogues, especially for young artists facing their first major exhibition. It’s about creating a collaborative environment rather than pitting artists against each other for resources. Despite limited resources, we allocated them thoughtfully. I mostly work with resources that I have, no matter how little they are, and think about what form they could take. And if the resources are even smaller, then we make decisions based on them and we can learn from it. Sometimes, having very little can mean having so much power because it allows you to make precise judgments and decisions, whereas when you have so much, you’ll likely just be all over the place.

Edited by Ewa Borysiewicz and Katie Zazenski

Imprint

| Exhibition | 35th Ljubljana Biennale of Graphic Arts |

| Website | bienale.si/en/ |

| Index | Ghana Hana Čeferin Slovenia The Ljubljana Biennial of Graphic Arts |