Nhớ: Space Between One End and the Other

Grandma, know that I miss you very much! I have longed for several years to be able to visit the Vietnamese countryside, to feel the smell of home, to see your face, to meet the rest of the family, and perhaps to see if I have outgrown you. Did you know that I am already taller than all the women in my family here?

I wrote my grandmother a letter 10 years ago. On an old computer, I typed the words without Vietnamese punctation marks with plenty of mistakes. I printed it out on my father’s printer and gave it to my mother to fill in the marks. Without them, the words wouldn’t make any sense. Only I could read them that way. I was about 17 at the time and had a great love for the person, even though I had met her only three times in my life. I was three, then five and finally fifteen when we met. And every time we were apart, I felt a huge affection for her. For it is with my grandmother’s story that all other stories begin.

Without her, there wouldn’t be my mum, and without my mum, I wouldn’t be here.

Without her idea of going to a better place, my parents wouldn’t have gone to Europe.

Without it, I would have lived a different life, maybe had a second child on the way.

I often ask myself who I would have been,

if I hadn’t been born in Slovakia.

For myself, it is a curiosity that a letter written to my Vietnamese grandmother can be read in Slovak. What coincidence of circumstances must arise for such a situation to occur at all?

Although I put my grandmother in the role of the original actor who plays out the whole story of our family, my father was the one who made everything happen. As children of our parents, we tend to forget that they have lives of their own. Ones without us. Or at least carry they imagine these lives. That they have or had their own ambitions, dreams, silly experiences, mistakes and we were equally full of doubts. I imagined what it was like to be my father when he became a migrant.*

This is the first exhibition of art of the Vietnamese diaspora in Slovakia. It is a sensory space and an invitation to dialogue, where personal memories can be shared and (re)discovered. The space contains words, both written and spoken. It contains stories, both told and silenced. The design of the space references the Vietnamese tone marks that indicate the six different tones of the Vietnamese language, a very subtle intervention into the space, but it’s the details that count when we want to communicate, connect, and share stories with others. It is a space where ideas of home can grow and where histories can be told, both personal ones and national ones, those cruel ones of war and forced migration. This exhibition, while basing its examples and stories on the second generation of the Vietnamese diaspora, wants to tell a more complex story about identity, culture, belonging, and how we are shaped and influenced by our families, as well as the society around us. It is a story about a heterogeneous group of the Vietnamese diaspora with different histories and contexts. The socialist experience of the Vietnamese in Czechoslovakia was different than in France, Germany or the US. While the exhibition does not aim to retell the story of French colonization, the Vietnam War, or American involvement in Vietnam, all of these events are nevertheless intertwined in the (hi)stories, personal family memories, and transgenerational traumas of the exhibiting artists. There are glimpses of trauma and loss in the works on display, but what unites these works overall, and what this exhibition focuses on, is our relationship to families. It looks for personal stories. What generational traumas do we carry within us? How does our relationship to family history inform and shape who we are? How do we preserve memories and how do they influence our present emotions? Memories can become a form of resistance; remembering can act as a way of presenting a diasporic, otherwise non-linear history.

When crossing borders, do you think about

what you will become on the other side?[1]

The word nhớ here is a metaphor for how a person living in the diaspora shapes their own story composed of memories and various longings for home. The exhibition explores diasporic experiences of communities who have often been forced by adverse circumstances to leave their place of birth in search of a ‘better’ home. Stuart Hall provides us with an important prompt when talking about the Caribbean diaspora: “How are we to conceptualize or imagine identity, difference, and belongingness, after diaspora? Since “cultural identity” carries so many overtones of essential unity, primordial oneness, indivisibility, and sameness, how are we to “think” identities inscribed within relations of power and constructed across difference and disjuncture?”[2]

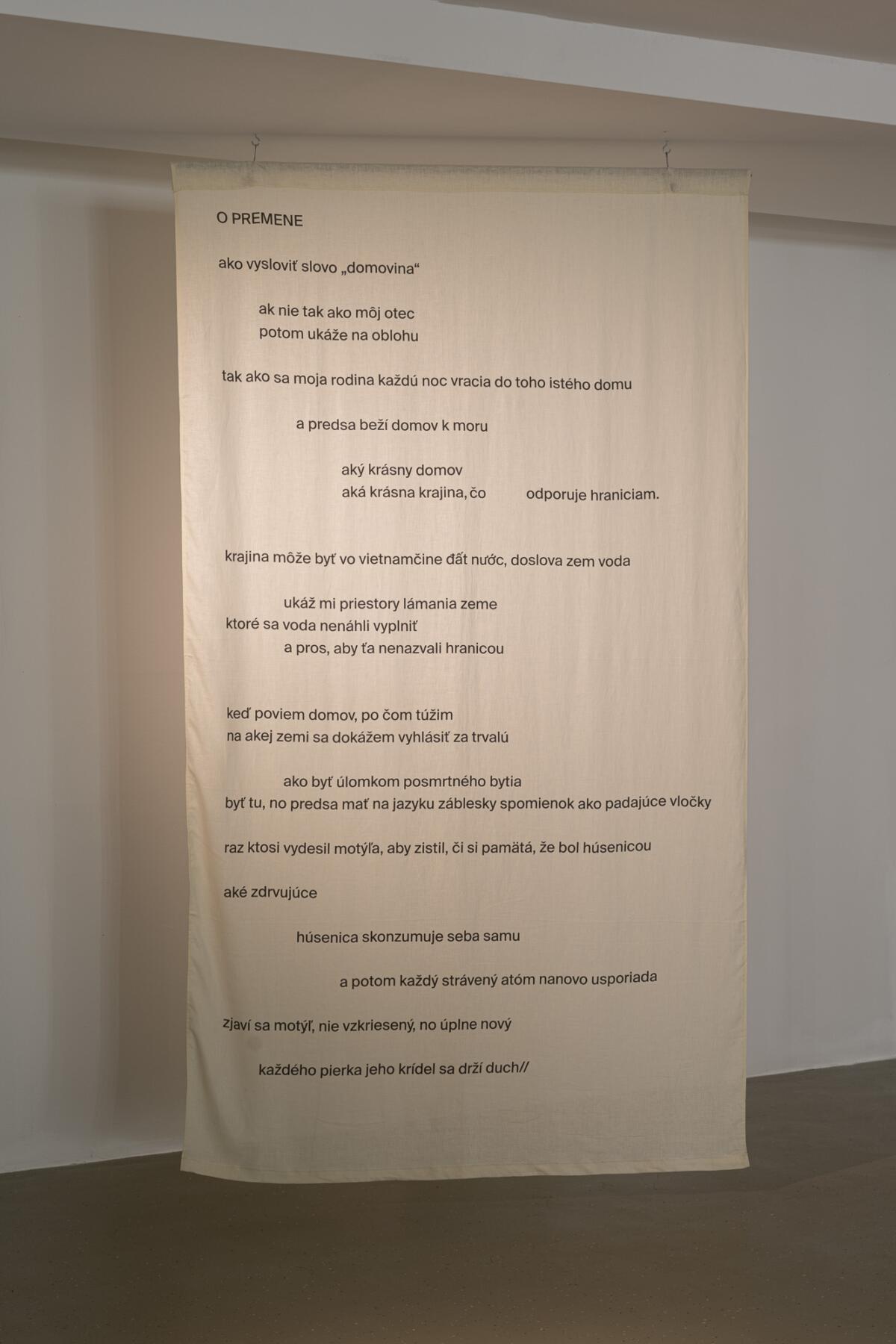

Upon entering the exhibition space, the voice of poet Kimberly Nguyen contemplates what home country is: “how beautiful a home. how beautiful the country that defies a boundary.” We are reminded that home is more than just a piece of land in the world where we were born, it is a feeling, it is a sense of belonging, even a process in transition, even when we cross borders…

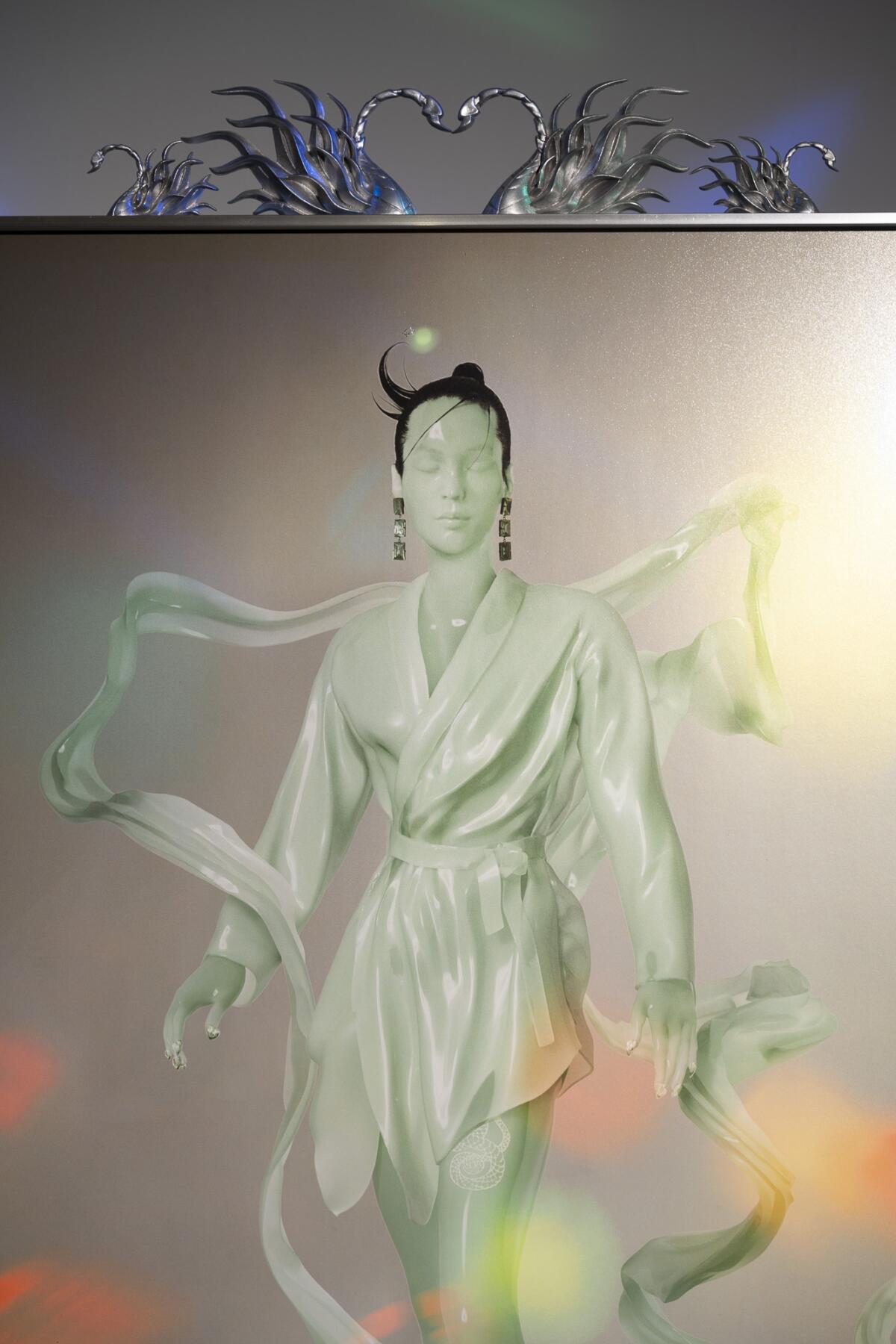

For most of us, our most vivid family memories are of family gatherings and celebrations. In her installation, Nhu Xuan Hua puts on a wedding party to recall all of these memories. “Wedding Room” from the series Hug of a swan, reminds us that often our most special memories emerge when we get together, when we sit down and share a meal. The installation consisting of karaoke lights, a stage and meticulously set tables would be the perfect backdrop for a great party, but wait, the tables are halved, the cutlery and plates are folded. The scene is at once close to reality, but also not at all. It is a rather surreal space. We are challenged by our own memories; Nhu Xuan reminds us of how elusive our memories are. Similarly, Nhu Xuan’s Family Portrait, from the series Tropism, consequences of a displaced memory, depicts a family at a wedding where the bride and groom and all of the wedding guests have blurred faces. They are morphed into their surroundings. How do we reconstruct our memories? Do they shape who we are? Or do we retain the feelings connected with moments rather than the exact details and facts?

In his video performance, entitled Performance with my father (II), Minh Thang Pham and his father talk about their relationship, which is affected by his son’s inability to communicate fluently in Vietnamese and his father’s lack of Czech. In the video, they look for connections and ways to communicate outside of language. Are we only able to fully understand each other through our ability to speak the same language? Or can we feel a deep connection through gestures, body language, eye contact, facial expressions and every day care and affection? As the artist’s dad explains, it is the tình cảm, the everyday gestures of love, that remind him of the love they share.

The child-father relationship is also the theme of the film Love, Dad, which is presented in the exhibition space A Black Box. It is an animated documentary about the lost connection between a daughter and her father. Diana Nguyen was separated from her father for a year as a child when he ended up in prison. However, during this period, paradoxically, they developed an even closer relationship, with the distance easily bridged by the letters they wrote to each other. Separation came again later in her life when her father left the family for good. The film is a mechanism through which Nguyen copes and rediscovers the lost connection and love with her father.

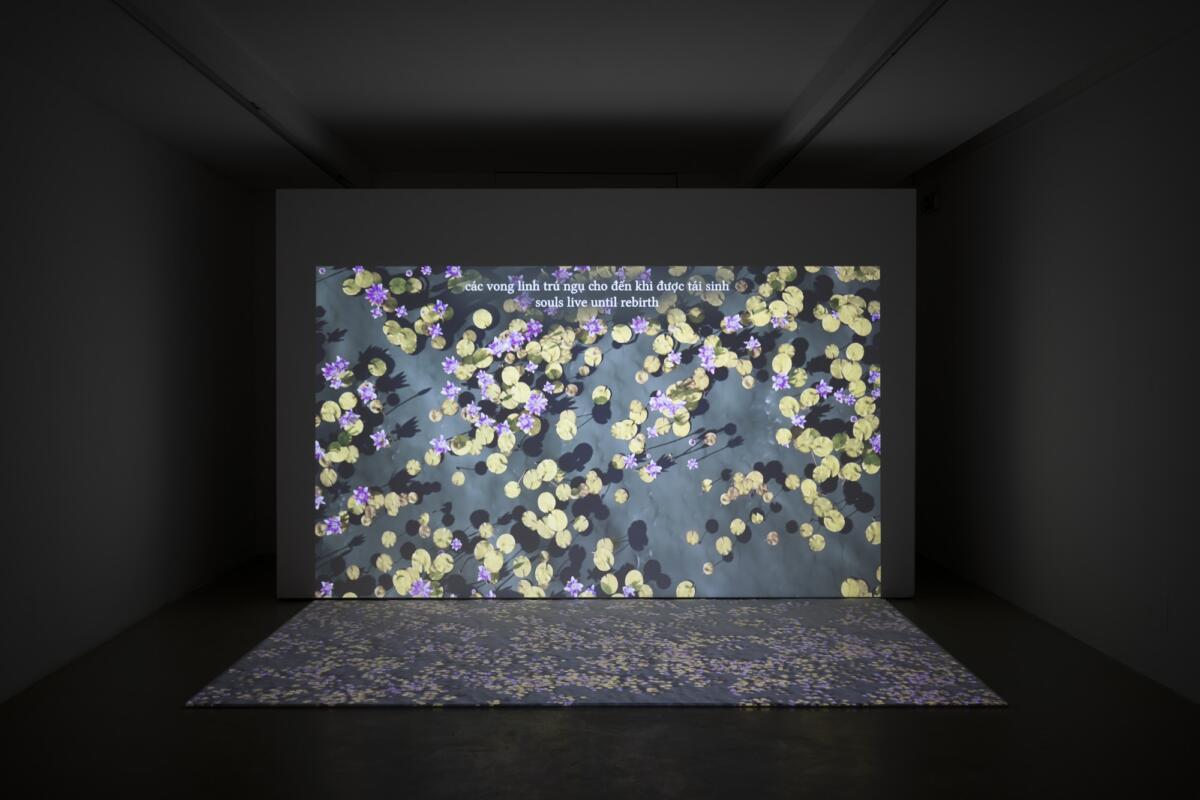

After the Fall of Saigon, the largest migration of Vietnamese, the so-called “boat people,” came to Europe, including France, West Germany, and the United States. Maithu Bùi’s two channel video installation, entitled Mathuật – MMRBX, aims to reveal the troubled past of survivor diasporas. “Mathuật” is a combination of the artist’s name, Maithu, and the Vietnamese word for magic, ma thuật, while MMRBX is an acronym for the memory box. Acting as a memory box, the video tells stories of Japanese occupation, American bombing, French colonial exploitation, and the intergovernmental agreement with the GDR. Filled with memories of colonization and decolonization processes, the video begins with a Vietnamese water puppet show. This ancient method of storytelling and dissemination of knowledge is a great tool for preserving past stories. Personal memories are mixed with the collective history of transgenerational traumas, allowing a new narrative of the Vietnamese diaspora to take shape.

This exhibition also encourages us to reflect on the fact that Slovakia is much more multicultural and vibrant than we often think. We often refer to former socialist countries as nationalist or xenophobic because they have lived in isolation for so long. But that is simply not true. There is an ‘often overlooked circulation of people, goods, knowledge and capital that took place between the state-socialist states and between these states and a number of developing countries.’[3] During the period of state socialism, from the 1950s to the 1980s, the mobility of university students and migrant workers was an important aspect of economic and political state-building in Central and Eastern Europe. Nearly 3,000 Vietnamese found a home in Slovakia and between 60,000 – 100,000 in the Czech Republic. Czechoslovakia offered roughly 500 scholarships to students from ‘developing countries’ annually, and among them, Vietnamese comprised the largest group.[4]

Kvet Nguyen’s work The Archive of Returns is an open archive of memories of her family. This repository of memories contains recollections captured by photographs of her parents’ arrival to Slovakia. From the installation object you can pull individual archival or preserved photographs capturing images of everyday life and family events. The box contains images (found, gathered or created by the artist), photographs from celebrations, family gatherings, and trips. What you choose to uncover and interact with from the series of memories is up to you. Our memory is a selective process, full of random processes and complicated overlaps with fabricated ideas. How do we archive our personal stories and what is worth preserving?

Imagine you are only 19 and you have decided to leave your home country with one small bag and just a few pieces of clothing. In her ceramics, entitled New Hope, Quynh Trang Tran traces the story of the journey of her parents as they emigrated from Vietnam to Czechoslovakia. Her goal was to create an object that would evoke the complex conditions that accompanied the journey, without knowledge of language, cultural and political customs and with only a few of the most basic pieces of clothing. Her mother was only 19 years old and her father was 22. Both came here under different circumstances and in different years. They only met once here, even though they both came from the same village in Vietnam.

The common thread in the migrant story is transportation, moving from one place to another. Fashion designer Anna Tran works with the theme by using the element of the checkered pattern, which she took from the checkered plastic raffia bags. For the artist, these bags, associated with migration,[5] are the symbol of memories of her childhood, of the nomadic way of life that accompanied her childhood in Moravia. In the bags her and her mother carried not only their personal belongings, but also items for sale, which later became their source of income. Anna’s abstract installation, created especially for this exhibition, in the shape of a cloud, is an instrument of transformation back in time, into her own family story. After the exhibition, Anna will use the fabric for her new fashion collection.

I imagine I’m 25 and I’m leaving my whole family behind. I’m going to a place where there are people I’ve called Westerners for years, a critical term for those who destroyed my homeland. They’ve done it repeatedly and now I’m going to become one of them. At least I will try to be. They are all counting on me. I am the chosen one of the family who has been given the privilege to leave, and this is the first time I have known the feeling of privilege. I probably would have stayed, too, if it weren’t for the poverty. We’d have enough of those rice paddies and small crab hunting if it wasn’t all collapsing. There are too many mouths to feed. That leaves the responsibility on me.

I may be going to a developed part of the world, but I’m going to live like the lowest class to send money home. There’s a lot more of it needed there. I heard about Czechoslovakia on the news. It’s supposedly a nice country with nice women, so says a neighbour who gossips all over the village. I also leave my own wife and first-born daughter, who doesn’t know me because she was born during the Sino-Vietnamese War, in which I fought. I am leaving behind a language that was probably not meant for me. My wife believes in destiny, but this Vietnamese one didn’t work out for us. I don’t know how I will learn another language that breaks my heart with its hardness and unfamiliarity.

I’ll forget the contortions of my own lineage, but I won’t even realize it. I break all friendships. It’s as if I’m erasing my past. I trade my own life for someone else’s. It seems to me sweetly distant. Will it still be me? The unknown and the strange are my new home. And whenever I return, I will be the one who left.*

In Vietnamese, the word for missing someone and remembering them is the same: nhớ. Sometimes, when you ask me over the phone, Con nhớ mẹ không? I flintch, thinking you meant, Do you remember me?

I miss you more than I remember you.[6]

Hall claims that the sense of a cultural identity, tradition, its truth to its origins, this “authenticity” is a myth – “with all the real power that our governing myths carry to shape our imaginaries, influence our actions, give meaning to our lives, and make sense of our history.”[7] In this world of multiculturalism and liquid modernity[8], we all have some sense of diaspora within us. “This is the familiar, deeply modern, sense of dislocation which—it in-creasingly appears—we do not have to travel far to experience. Perhaps we are all, in modern times—aſter the Fall, so to speak—what the philosopher Heidegger called “Unheimlichkeit”: literally, “not-at-home.”[9] In the context of former socialist countries, the Vietnamese community is considered an “unintended diaspora”, “those students, trainees and workers who were expected to return home.”[10]

The line between the concept of one true home and nationalism is very thin. Hall reminds us that this is precisely the issue, that we cannot live without hope, but at the same time there is a problem when we take it too literally. “It is, aſter all, precisely this exclusive conception of “homeland” that led the Serbs to refuse to share their territory—as they have done for centuries—with their Muslim neighbors in Bosnia and justified ethnic cleansing in Kosovo. It is a version of this conception of the Jewish diaspora, and its prophesied “return” to Israel, that is the source of Israel’s quarrel [sic] with its Middle Eastern neighbors, for which the Palestinian people have paid so dearly and, paradoxically, by expulsion from what is also, aſter all, their homeland.”[11]

We, the second generation of the Vietnamese diaspora, have been in the West since birth or early adulthood. We are the children of those who came here but were not born here. This generation is the generation that receives much of the legacy of intergenerational trauma. The complicated emotions of uncertainty and the disconnectedness of two worlds. Like our parents, we ask ourselves the questions “what would it have been like if we had stayed in Vietnam?” But at the same time, unlike them, we are free from the direct influence of political events in Vietnam. This hybrid position drives us to understand our roots – all the more so when they are uprooted and planted in a new land. It allows us to operate on the margins, to balance and grasp the ambiguous tendencies of a blended identity.

The space between one end and the other. We are like constantly oscillating molecules that encounter limits but also openness in a new land. They are bumps in the contrasts we have been brought up on. Is there a right answer in fluidity? How does integration and assimilation enter into the process of recognition? Where does our memory end and another one begins?*

Perhaps we shall give up altogether or rather expand the idea of home. Just as Sophie Lewis teaches us to “abolish the family,”[12] we should abandon the idea of homeland. Not to lose something, but to expand it widely. Home can be a complicated, multi-layered, intricate sense of belonging to this world with overlapping influences, languages and memories. The two curators of this exhibition, one born to Vietnamese parents in Slovakia, the other a Slovak who spent her entire adulthood outside of Slovakia and completely lost her sense of “homeland”, invite you to contemplate the theme of belonging and home.

A stroke on the cheek for a re-membering combat against forgetfulness.

By exposing all of this I am talking to my father and I am holding the hand of my mother.

With the countless languages that I have been given to speak.

Whether out loud or in silence Most of the time in silence.[13]

Denisa Tomková

*Kvet Nguyen, some of these excerpts will appear in the upcoming Kvet’s book (N Press, 2024)

[1]Kvet Nguyen, 2021. Is the edge of the world a place from which to speak the world?

[2]Stuart Hall in Catherine Hall and Bill Schwarz (eds). 2018. Stuart Hall: Essential Essays, Identity and Diaspora. Volume 2. Duke University Press, p.208.

[3]Alena Alamgir. “Mobility: Education and Labour” in James Mark and Paul Betts (eds). 2022. Socialism Goes Global. The Soviet Union and Eastern Europe in the Age of Decolonisation, p. 290-291.

[4]Ibid, p. 312.

[5]They were already used by other artists from the region of Central-Eastern Europe, e.g.: Yulia Kostereva, Yuriy Kruchak and Ghenadie Popescu. See: Amy Bryzgel. 2016. “Street appeal: a decade of socially engaged performance art from the former East” in New East Digital Archive: https://www.new-east-archive.org/articles/show/5393/performance-participatory-art-new-east

[6]Ocean Vuong. 2019. On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous: A Novel. Vintage. Penguin Press, p. 186.

[7]Stuart Hall. 2018, p. 209.

[8]Zigmund Bauman. Liquid Modernity. Polity Press. 2013.

[9]Hall, p. 208.

[10]Christina Schwenkel. 2017. “Vietnamese in Central Europe: An Unintended Diaspora” in Journal of Vietnamese Studies (2017) 12(1): 1–9, p. 2.

[11]Stuart Hall, 2018, p. 210.

[12]Sophie Lewis. 2022. Abolish the Family: A Manifesto for Care and Liberation. Verso.

[13]Nhu Xuan Hua: https://huismarseille.nl/en/exhibitions/nhu-xuan-hua/

Imprint

| Artist | Maithu Bùi, Diana Cam Van Nguyen, Kimberly Nguyen, Kvet Nguyen, Minh Thang Pham, Anna Tran, Quynh Trang Tran, Nhu Xuan Hua |

| Exhibition | Nhớ: Space Between One End and the Other |

| Place / venue | A RING & A BLACK BOX, Kunsthalle Bratislava |

| Dates | 06.09. – 13.10.2023 |

| Curated by | Kvet Nguyen, Denisa Tomková |

| Photos | Adam Šakový |

| Index | A RING & A BLACK BOX Adam Šakový Anna Tran Bratislava Denisa Tomková Diana Cam Van Nguyen Kimberly Nguyen Kunsthalle Bratislava Kvet Nguyen Maithu Bùi Minh Thang Pham Nhu Xuan Hua Quynh Trang Tran Slovakia |