Learning from Minecraft – Zuzanna Skurka

‘What do you want, brick?’––Louis Kahn instructed his students to ask the material for advice if they are ever stuck for inspiration. If a brick desires to become an arch, he taught, it shouldn’t be replaced by cheaper concrete, but rather one should listen to the material and follow its lead. But what if the brick doesn’t want to be an arch, or a load-bearing wall, or a dome, or any other standard architectural element it has been for millennia? What if it wants to become a thermal insulation, a flexible, semi-transparent screen, or even a garment? Kahn’s architectural language evolved from the universality of international style to the monumentality and expression of form inspired by ancient architecture, influenced by his travels through Italy, Greece, and Egypt. In Kahn’s interpretation of functionalism modern technologies and materials were meant to merge with formal lessons drawn from historical architecture. But let’s go a step further and ask what ancient technologies can teach us.

As one of the oldest, most widespread, and versatile building materials, brick has served as the cornerstone of Sumerian ziggurats, gothic cathedrals, Indian stupas, the Great Wall of China, countless public and residential buildings in London during the industrial revolution, the first skyscrapers; the list could go on and on. The history of architecture is largely the history of brick, its manufacturing methods, and its refinement. Brick doesn’t have a single identity. It can be sun-dried or fired, cubic or decoratively shaped, raw or glazed, it could bear the mark of a craftsman’s hand or be industrially standardized. As a processed piece of clay, it’s both natural and artificial.

In the 18th century, brickmakers evaluated the potential of new clay sources by literally tasting the local soil––taking a clump in their mouths to assess its composition. Shortly after, the industrial revolution completely changed the traditional methods of brick production. Its local allure is now merely a romantic myth––over three-quarters of all bricks produced worldwide are currently manufactured in Southeast Asia. In the fulfilled dystopia of late capitalism, is it possible to have a different approach to materials? The post-war rebuilding of Warsaw was conducted with many bricks recovered from so-called Regained Lands. Its ‘rising from rubble’ was made partly possible by the post-German ruins. In a sense, the architectural tradition of spolia was once again resurrected. In Latin, ‘spolia’ means spoils, loot taken in plunder. They have symbolic, mnemonic, and political functions, serving to emphasize cultural continuity and power legitimacy, but it doesn’t end with that. Builders of the early Christian era used a different, less militarily charged term – ‘redidiva saxa’, meaning literally renewed or reborn stones.

Today, renewal of previously used materials is one of the fundamental challenges of architecture. Brenda and Robert Vale in their 1991 book ‘The Green Architecture. Design for a Sustainable Future’ listed limiting new resources among the six principles of sustainable design. ‘A building should be designed to optimize existing materials by minimizing the use of new materials, which at the end of the building’s life can be reused to form other architectural structures,’ they wrote. William McDonough echoed them a year later in the ‘Hannover Principles’, advocating for the ‘elimination of the concept of waste’ and ‘evaluating and optimizing the full life-cycle of products and processes, to approach the state of natural systems, in which there is no waste’. Although the era of starchitects and architectural spectacle luckily seems to be coming to an end, the technocratic and capitalist logic underlying it does not die, deceptively masquerading as sustainable design. But does extending the life cycle of building have to mean engineering ‘smart’, nanostructural, self-healing materials? Ongoing research into bricks, mortars, and concrete used in ancient Rome indicates physicochemical properties of these materials that are akin to today’s smart technologies, allowing them to adapt to atmospheric conditions and not only self-heal but even reinforce in spots where they cracked.

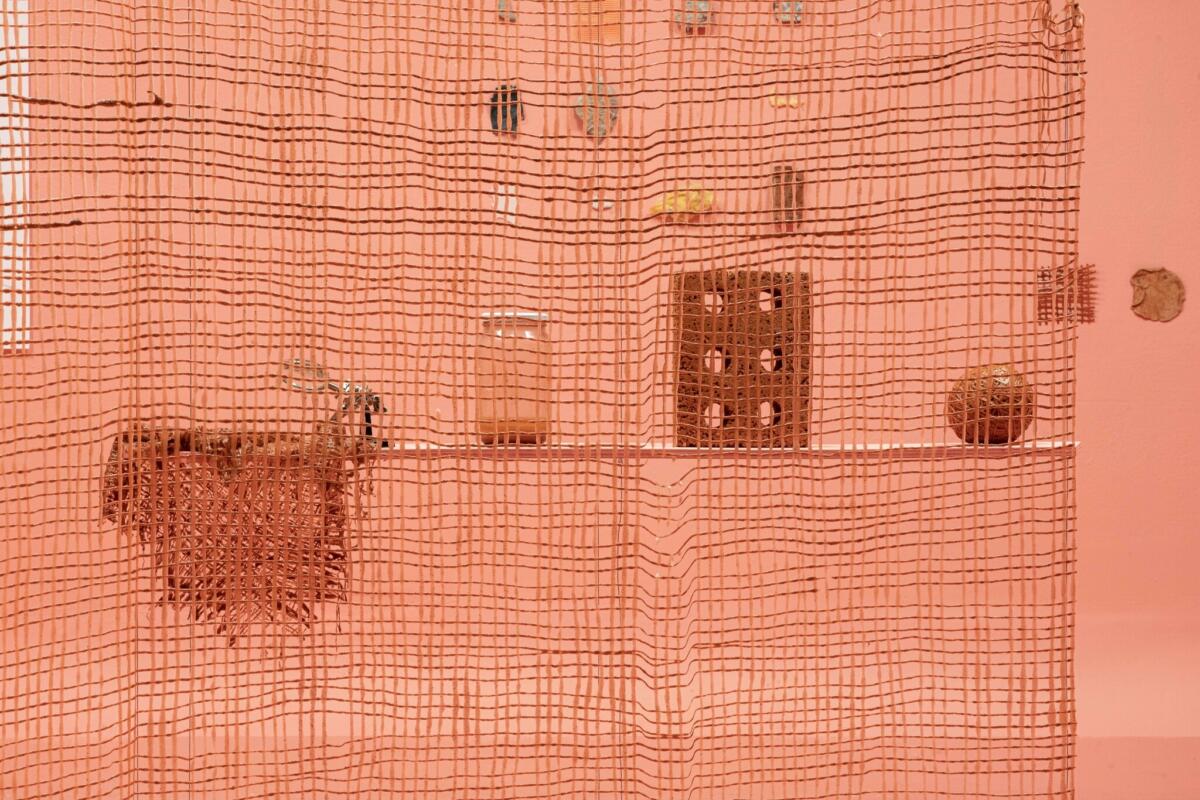

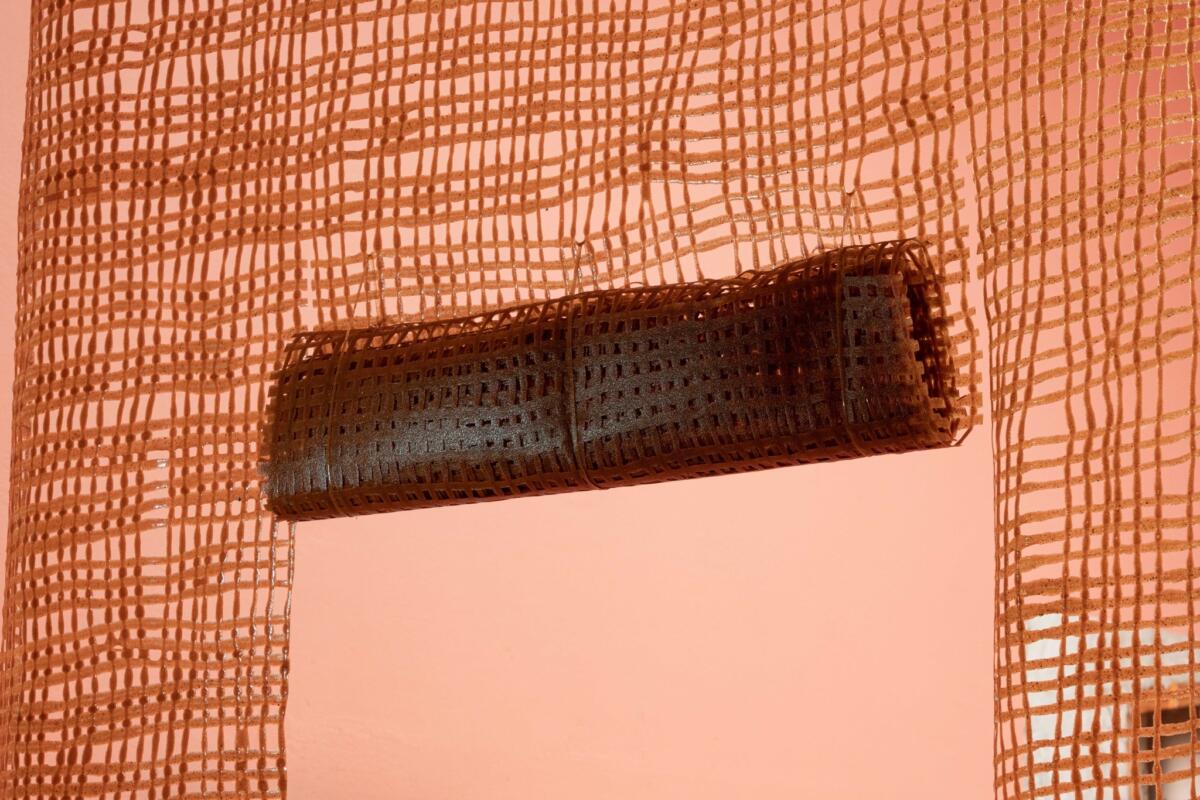

None of the objects in this exhibition is art, even though they might appear as such. They are all, essentially, bricks, even though none of them resembles one. Zuzanna Skurka, in her interdisciplinary research, examines the potential of brick. She explores how new, locally produced bricks can look like today, based on a wide range of materials rather than exploitation of the Earth’s resources. She also investigates what forms and properties the material obtained from brick remnants can take. Its potential seems almost unlimited – it can become hard or soft, brittle or flexible, replacing both styrofoam and concrete. As in preindustrial utopia of ‘Minecraft’, where there’s no synthetic materials, only crafted and enchanted natural elements, the brick gains new, unexpected forms, prompting a rethinking of the principles of design itself.

Imprint

| Artist | Zuzanna Skurka |

| Exhibition | Learning from Minecraft. All The Things You Can Make With Bricks. |

| Place / venue | Art Industry Standard Gallery, Kraków |

| Dates | 25.08 – 17.09.2023 |

| Curated by | Piotr Policht |

| Exhibition design | Bartek Buczek; Marcel Kaczmarek |

| Photos | Michał Maliński |

| Index | Art Industry Standard Gallery Bartek Buczek kraków Marcel Kaczmarek Michał Maliński Piotr Policht poland Zuzanna Skurka |