The interview was conducted in Polish and was originally published at Szajnmag.com. BLOK thanks the authors and the team at Szajnmag.com for their permission to publish the piece in English on Blokmagazine.com.

On a sunny Saturday afternoon, I head out to meet the artist Liliana Zeic. Before I reach the Artivist_Lab gallery, I walk by Powder Gate in Prague’s old town. I turn onto Hybernská Street and here I am on the patio, facing the entrance to the exhibition entitled “Group Practices”. Around me, people sitting at tables are talking, drinking wine and smoking cigarettes. The spring evening promises to be nice and pleasant.

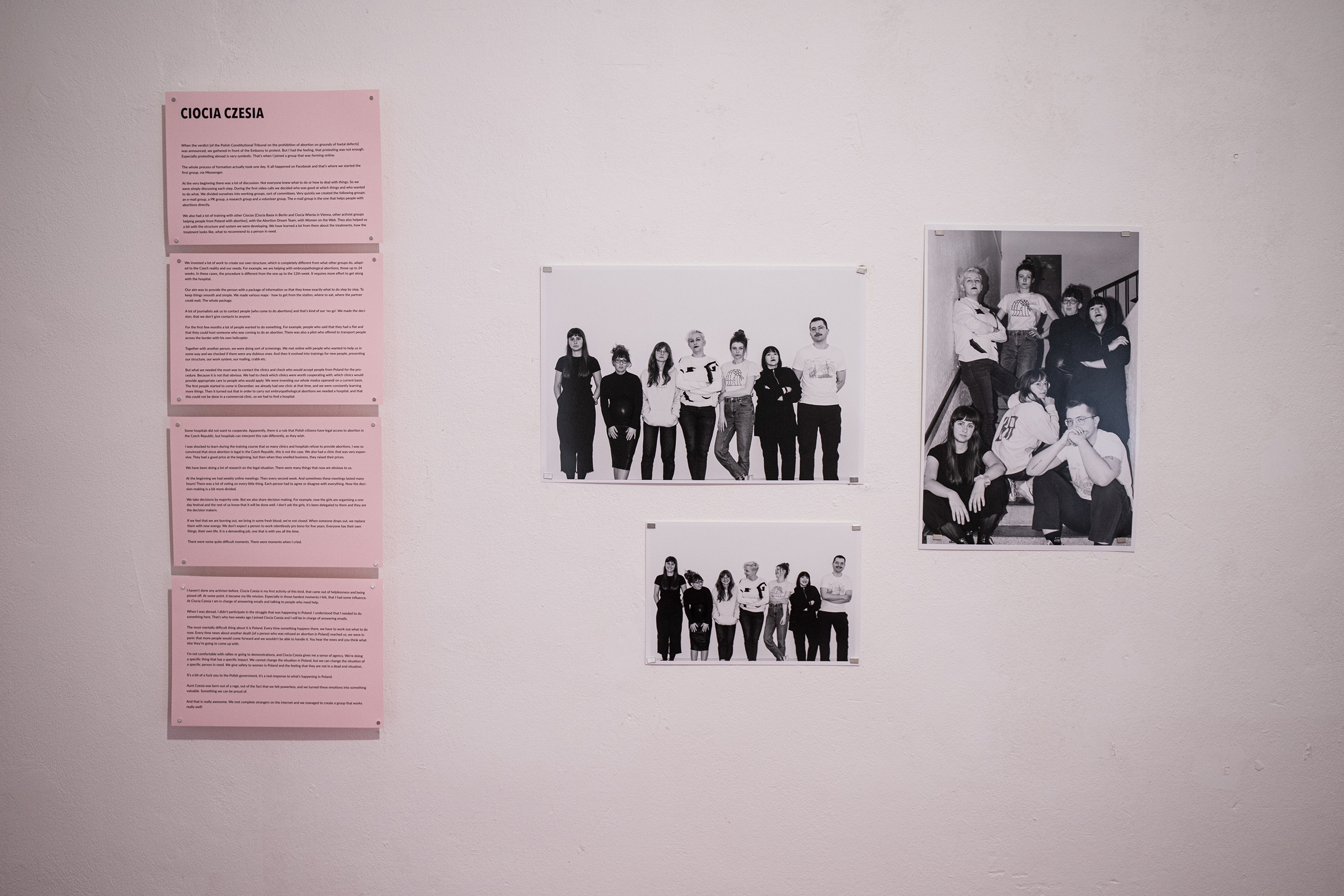

The viewers are introduced to the show with a curatorial statement: The project, started in 2019, contains a series of conversations and photo portraits of feminist activist groups operating in different cities in Poland that are connected to the Black Protests or Women’s Strikes – the nationwide movement responding to the attempts to restrict the abortion law in Poland. During the meetings with the groups from cities like Bydgoszcz, Toruń, Kłodzko, or Poznań, Zeic focuses on the experiences, challenges, and goals of the interviewed activists as well as the ideas of collectivity they are practicing. Therefore the cycle reveals the backstage of activist work, reflecting on the invisible labor, precarious infrastructure, and personal relations as the core of resistance practice”[1].

Aleksandra Łukaszewska: How long did it take you to collect the material? How did this process commence?

Liliana Zeic: I completed this project in a very short time – it took me six months – about three years ago. I haven’t come back to it since. Back then I was still part of Manifa, a group that advocates for women’s rights, active in my hometown. Out of a huge fascination with collective practices and feminist collectives, an idea emerged to capture their work in a very simple and unmediated way, without focusing on the most public, loud and perceptible manifestations of activism, such as demonstrations or press headlines. I wanted to show the other, mirror side of activism. The invisible work that is done so that certain actions may be possible. That was the source for my idea. At that time I had more contact with activist spaces. I was learning to be a trainer and facilitator who helps activist groups. I have always been interested in the ways and tools that allow us to transcend the hierarchical and patriarchal structures and norms we are used to. While working on an exhibition in Poznań at the time („Side Effects”, 10.05 — 16.06.2019, Arsenal Municipal Gallery in Poznań[2]), I had to confront myself with the double role of being an artist and an activist. That’s why I proposed that the groups meet and talk in order to get to know their ways of being together. I mainly used photography and interviewing tools, sometimes I focused more on one, and at times, more on the other. The result of the meetings is what you can see in the exhibition, this very tiny piece of the landscape that is the Polish activist movement. I added another part to my exhibition in Prague – my meeting with Ciocia Czesia (eng. Auntie Czesia).

Was it you who invited Ciocia Czesia to cooperate?

Curator Tomek Pawłowski-Jarmołajew suggested it. I was very happy about that. I know Ciocia Czesia and I respect her for offering Polish women help with abortion. I thought it was a great idea not only to do an interview and take photos, but to offer to share the exhibition space with the people from the activist group. For the duration of the show, for two months, the activists can use the gallery space for their own purposes. I think it’s important to connect these two areas. To get used to one another.

Why did you choose Prague?

The decision stems from the profile of the gallery, which focuses on minorities who live in Prague. This is another exhibition from the gallery’s series about the margins of Czechness. The entire collective of Ciocia Czesia have lived in Prague for many years. They are rooted in the context, quite well recognized in Prague, while being migrants at the same time.

You show a very interesting perspective. I’ve been watching Ciocia Czesia for some time. I imagined their work as a large and efficient organization. Here I can see their faces. And it turns out that this is a small group that does great work.

Absolutely. They met on the internet, gathered over Facebook messenger and started working together. At this point they are helping up to a hundred people a month. The girls, migrants, realized that they are not able to participate in the struggle in Poland every day, and so decided that they will help in the place where they live. They are doing something very important: they bring concrete help to people in a situation of crisis, which is especially crucial since in the Czech Republic, only abortion due to embryopathological conditions is legal until the 24th week of pregnancy (counted from the first day of the last menstrual cycle). [3]

It was not difficult for me because I am not an outsider. I come from two worlds: art and activism. But it is, indeed, a challenge because these two worlds often don’t trust each other. They use very different definitions of feminism or queerness. What I find very interesting is the multitude of ways that activist groups operate on a daily basis. You encounter closed and open groups, hierarchical or not, different ways of making decisions, thinking about making decisions. We are used to thinking that whoever is louder or whose position gains more support, wins. And yet there are more ways of deciding. One of them, for example, is consensus. This is not an easy way, because it means that the decision that is made in the group, is made with consent of each participant. In the very end, you reach an agreement that is satisfactory to all members.

Do you consider yourself an artist or rather an activist?

I feel more like an artist. I refer to myself as an artist with an activist background. Art is my job. It is a profession from which I make a living. I am an artist who reflects on the hierarchies in the system in which I have come to function, including the art world system. I am definitely an artist, although this exhibition is not that „artistic”! It is different compared to what I do every day. There is little metaphor and mediation here, simplicity dominates.

Where does this austerity in the narrative of the exhibition come from?

We adjusted the project to the gallery’s profile, which is to combine activism and art, and to the desire to share the space with an activist group. That’s why I didn’t add any metaphors, any other projects, I went for a simple juxtaposition.

Do you think it is possible to be apolitical in art?

It’s not possible. It is impossible to be apolitical in life. People who think they can make apolitical art have privileges that they don’t acknowledge. They don’t notice that they are acting from a political position, even as normative, heterosexual, white men – perhaps even more so. I think that – as a queer lesbian from Poland – my very existence is political.

You collected materials for the exhibition three years ago. Does it have any meaning?

Yes, the only works produced now are the photographs and a conversation with Ciocia Czesia. These images are a timestamp. Only now do I see what a tiny fragment of reality this is, all that was happening in Poland at that time. Ciocia Czesia emerges in a completely different political moment, in a different context of the fight for reproductive rights. The group was formed about a year and a half ago, that is, when the Constitutional Tribunal in Poland banned abortion due to fetal defects, further limiting the already restrictive law. In doing so, it created one of the most radical reproductive laws in Europe. Ciocia Czesia arose out of an even bigger anger.

In retrospect, do you think that activism has changed?

Definitely. Looking back at those conversations I had three years ago, now, I notice that a lot has changed. There has been an increased acceptance for what is illegal. There is also more acceptance for civil disobedience. Activism is less polite, it has become more everyday. It is a structure, a base, that cannot be taken away. They’ve been around for a while and it’s very easy to spur them into action when the need comes.

As an artist, what interests you most in the process of forming such groups?

I remember when I first met with Women’s Strike Wrocław. At the time, it was a nucleus of the National Strike. In Wrocław in 2016, a movement was created that had an impact on a huge scale. It was touching and beautiful for me to visit the home of Marta and Natalia, who were creating its structures in their living room, over coffee and tea. These meetings were very homey. The fact that they were – and still are – held in apartments, in workplaces, is very important. Toruń’s Dziewuchy (Tough Girls) met in the furniture showroom owned by one of their own members. These are places that are very different from demonstrations.

Are you interested in the contrast of those two worlds?

Absolutely, I love that contrast. On the one hand, there is this warmth and domesticity, on the other: demonstrations taking place on the streets. I am fascinated by the feminism and radicalism that is born in the kitchen.

Is that what you wanted to show in the photos?

Yes. That’s why these are pictures of people meeting over tea and cake. These are not pictures of masses, thousands of people protesting in the streets, they are not “sexy” in a media-friendly way. These are moments of effort and togetherness. In my view, this is the underbelly of demonstrations, the other side of activism that usually remains invisible. Hours of work, setting up, getting along, making decisions, writing texts and sharing responsibilities. And afterwards, the visible actions are generated by the few loud people who can speak up. This is why I believe that the media and roles of visibility should not end up in the hands of only a few leaders. I think they should be rotating. Many groups don’t think so. It’s very easy to hijack the spotlight and think that this one person who speaks created the movement, and that’s not the case. The movement is created by the people who do the hard work that you don’t see.

Would you like to think of it as collective work?

Yes, exactly.

Was it important to you in this exhibition to show that being an activist is work?

Yes, it is many hours of work that you do for free. A chunk of your life that you devote to activism. It is also an emotional effort.

Edited by Ewa Borysiewicz and Katie Zazenski

Liliana Zeic (formerly Liliana Piskorska) – born 1988, visual artist, holds a PhD in Fine Arts, queer feminist. In her artistic practice she analyses social issues from the perspective of radical sensibility, deals with the subject of queerness and non-heteronormativity and draws on her experiences of growing up in the region of Central and Eastern Europe.

Text: Aleksandra Lukaszewska – a graduate of cultural studies with a specialization in art criticism at the University of Wrocław. Currently an intern at the Artists-in-Residence program at MeetFactory in Prague. She is interested in cultural and artistic activities that address important social issues.

The exhibition “Group Practices” was on view at the Artivist_Lab gallery in Prague until 31.05.2022.

[1] https://www.artivistlab.info/1012/group-practices, last accessed: 14.06.2022.

[2] https://arsenal.art.pl/en/exhibition/side-effects/, last accessed: 14.06.2022.

[3] Abortion in the Czech Republic is legally allowed on request up to 12 weeks of pregnancy, with medical indications up to 24 weeks of pregnancy, in case of grave problems with the fetus at any time. See: https://abort-report.eu/czech-republic/, last accessed: 20.06.2022.

Imprint

| Artist | Liliana Zeic |

| Exhibition | Group Practices |

| Place / venue | Artivist_Lab |

| Dates | 23 April - 31 May 2022 |

| Curated by | Tomek Pawłowski-Jarmołajew |

| Photos | J.Rabara |

| Website | www.artivistlab.info/ |

| Index | Aleksandra Łukaszewska Artivist Lab Ciocia Czesia Liliana Piskorska Liliana Zeic Tomek Pawłowski Tomek Pawłowski-Jarmołajew |