Ewa Borysiewicz: One of the things that struck us most during the ceremony of the Igor Zabel Award in Ljubljana in November 2022, was its familial atmosphere. One could genuinely feel the difference compared to other similar art world related events.

Bojana Pejić: I was quite surprised as well. These corona years I mostly felt very physically isolated and did not have many opportunities to meet people. So I was a little bit afraid to be in a crowd again. But it was so warm, friendly, and amazing. I did some kind of a pathetical speech, but most importantly, I felt like I was coming home. This was also twelve years after the “Gender Check” exhibition[1] and during this time we continued to keep an exchange with colleagues involved in the show, but not in the form of physical contact. So I was really touched by the response of the people and their presence.

EB: It seems that friendship plays a key role in your professional practice as well?

Absolutely! In the summer of 2022 I was invited by a young curator, Dejan Vesić, to talk about my curatorial work in the Center for Cultural Decontamination in Belgrade – it is an anti-Milosević, anti-nationalistic place of historical importance. I was planning on mentioning “Artist-Citizen”, a very important show for me personally, which was organized during the October Salon in 1998 and was my attempt to highlight artist’s gestures towards undoing nationalist ideologies in every possible context. And when preparing for this talk I realized that in fact, my projects were all about friendships. Artists and colleagues that were invited to take part in each project were always crucial. But it’s also about mutual understanding and respect – not fascination. And our friendship with Edit András and Piotr Piotrowski – whom I loved incredibly – and so many more, were both based on our work and formed during our working together. And once more, I am so grateful to Anetta Mona Chişa, one of my dear friends whom I exhibited many times, who suggested me for the Igor Zabel prize. In this sense, I’m a rich, rich person.

Vera Zalutskaya: Do you think that the topic of the so-called post-communist or Eastern European art is what connects people so much?

There’s no simple answer to this question. When we started to work on the “After the Wall”[2] exhibition in 1999 in Stockholm (the show later traveled to Budapest and its last stop was here, in Berlin, in 2001) it was important for me to connect colleagues who probably never worked on one common project. From my point of view, this was somehow a gesture of offering a platform. But this platform, the exhibitions, including “After the Wall” and “Gender Check”, were offered to me as well. I was given the chance and I opened the access to many other colleagues. I always remember that I didn’t walk alone in all this. And I’m really grateful for their cooperation. Nevertheless this issue of what I call “East-Centric Art”, it was something that brought us all together.

VZ: I am curious to know where this interest originally comes from and when did you begin to work with this topic?

Until now I’m living in Berlin – it’s been 30 years – but the first years in Berlin I did write a lot about Western artists and did a lot of reviews and articles for Artforum in New York. In the 90s, Germans were not so concerned with our Eastern stories because they had their own problems: there was the German unification and so on. It was more about, let’s say, local art. But the fact is, if I had stayed in Belgrade I don’t believe I would have established this kind of interest, for the art of my neighbors. Yugoslavia was a country under a different kind of state socialism, in contrast to Albania or even Estonia, because it was an open country and we had foreign artists coming there. We could travel, we could buy foreign books. It was the flow of information which constituted us as art critics and then art historians in Yugoslavia. When living in Belgrade, I started to write reviews of local exhibitions and also foreign exhibitions like Documenta, Kassel, the Biennale in Paris or the Venice Biennale. I was working in the Student Cultural Center in Belgrade, which in fact acted as the Institute of Contemporary Art, having a gallery, theater, film program, lecture program and so on. In addition, it was completely internationally oriented since its opening in 1971. So when I came to Berlin I was equipped with this openness towards other parts of the world. Previously I curated small projects, but I never before was involved in such a huge project like “After the Wall” in 1999. This was the idea of David Elliott, a British art historian who was the director of the Museum of Modern Art in Oxford for 20 years. He exhibited the Soviet avant-garde and also did one exhibition with Socialist realism. When he became director of the Moderna Museet in Stockholm, he manifested his interest in contemporary art in Socialist, post-communist Eastern Europe, and what was happening there ten years after the fall of the wall. And he invited me to curate such a show. So “After the Wall” was somehow offered to me by a colleague with whom I didn’t work closely before.

EB: How did the preparations look for a show on such a scale?

As you know, the fall of the wall in Berlin in 1989 was not really an event that affected Eastern Europe immediately. The research for this project in the end of the 90s was a bit easier because at that time the Soros Centers for Contemporary Art, a part of the Open Society Project by George Soros, had already been working in the capitals of 20 Eastern European countries. So they collected the documentation, followed the activities of contemporary artists, made annual exhibitions, etc. The starting point for us was to visit these Eastern European countries. We started in 1997 and the exhibition opened in October 1999. Of course we could not rely exclusively on the materials from the Soros Centers, they had their own policy. I knew that in each country there were other so-called “marginal artists” who were not in the focus of the Soros Centers. I was talking to people whom I knew from catalog texts and so on. During this research many artists proposed other artists, because at that moment, there was still no competition between them because the capitalist art market in the Western sense was not yet functioning. And it was wonderful because apart from the exhibitions we had symposia, presentations… And many people with whom I worked later, like Piotr Piotrowski and Edit András, my dearest colleagues, they really met in Stockholm and then after that, continued to cooperate. At that time I was not so interested in what the so-called “Western audience” would think about the exhibition, whether they would understand it or not. I was really afraid about the opinion of my Eastern colleagues, because it was the first exhibition of contemporary art of post-communist Europe in Europe. I was wondering how they would judge this de facto patchwork-readymade.

EB: How did you approach the structure of the show so it would not be perceived as a “patchwork-readymade” as you put it?

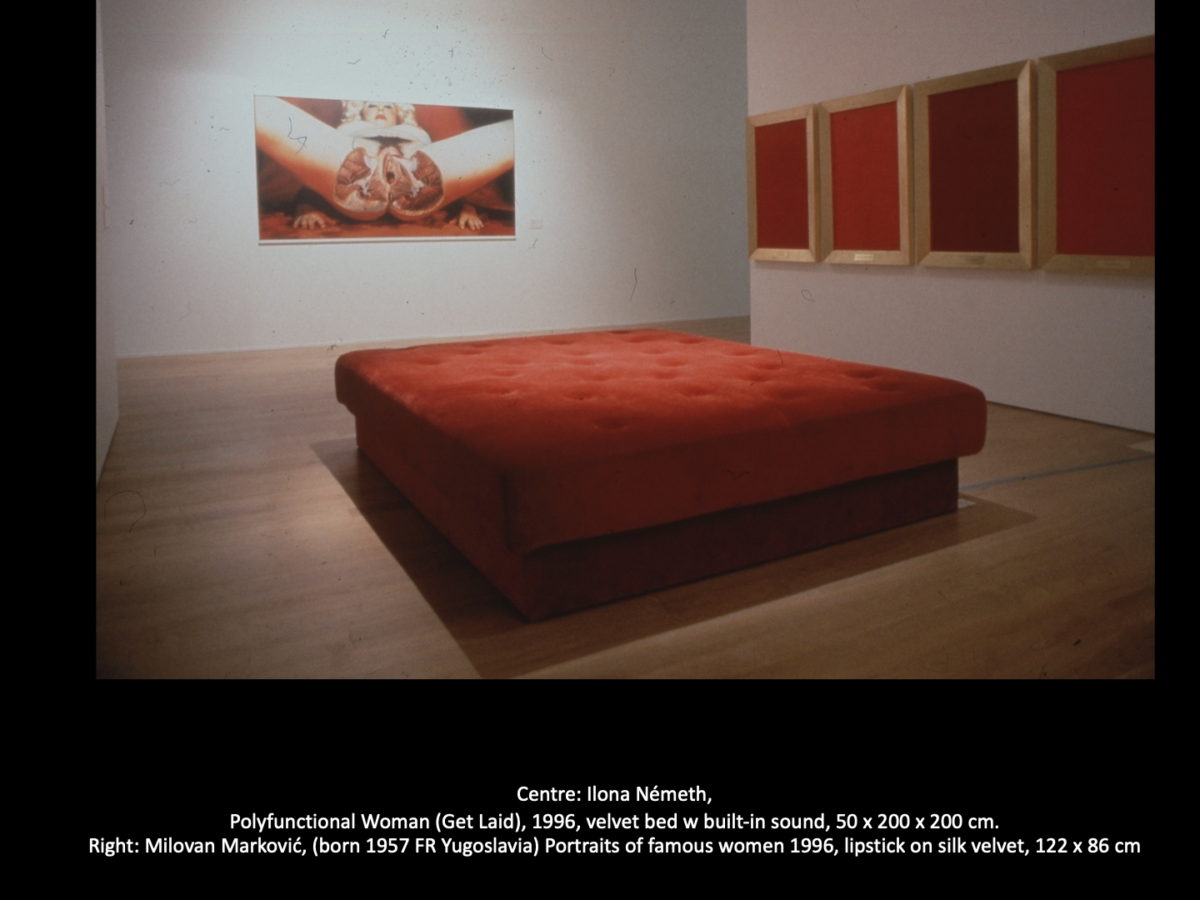

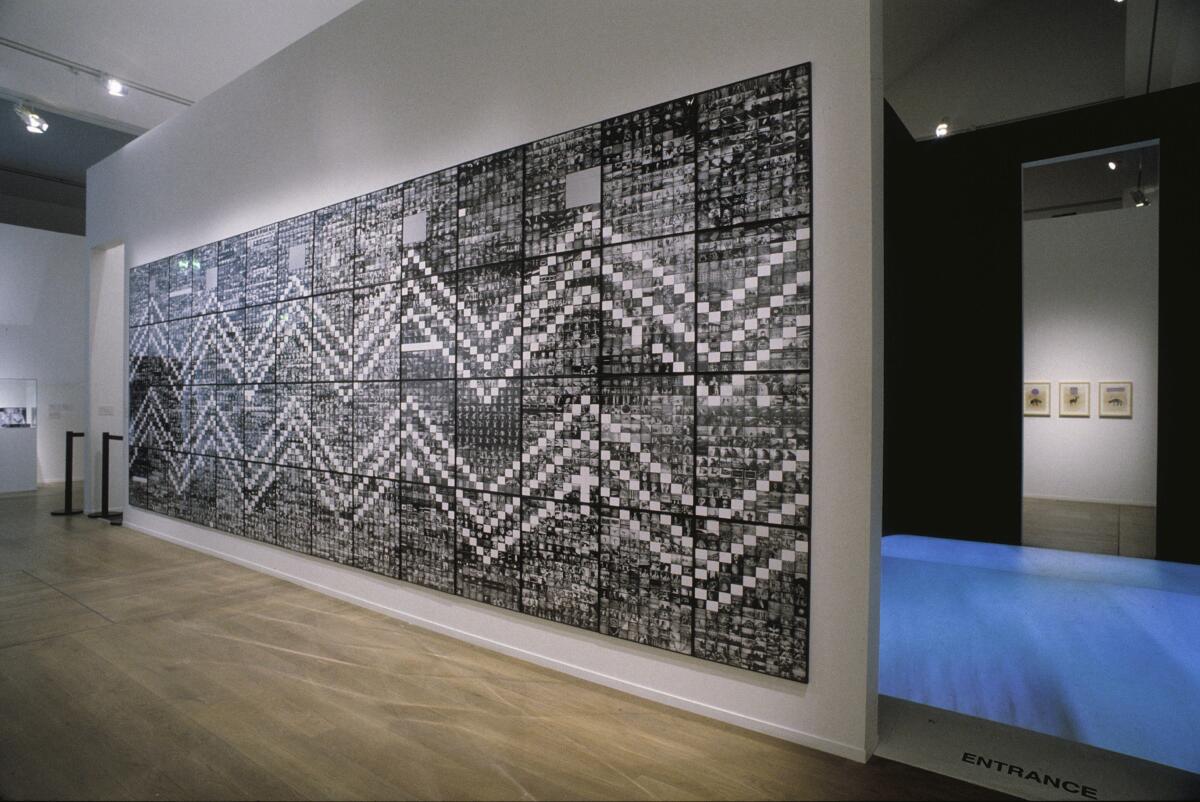

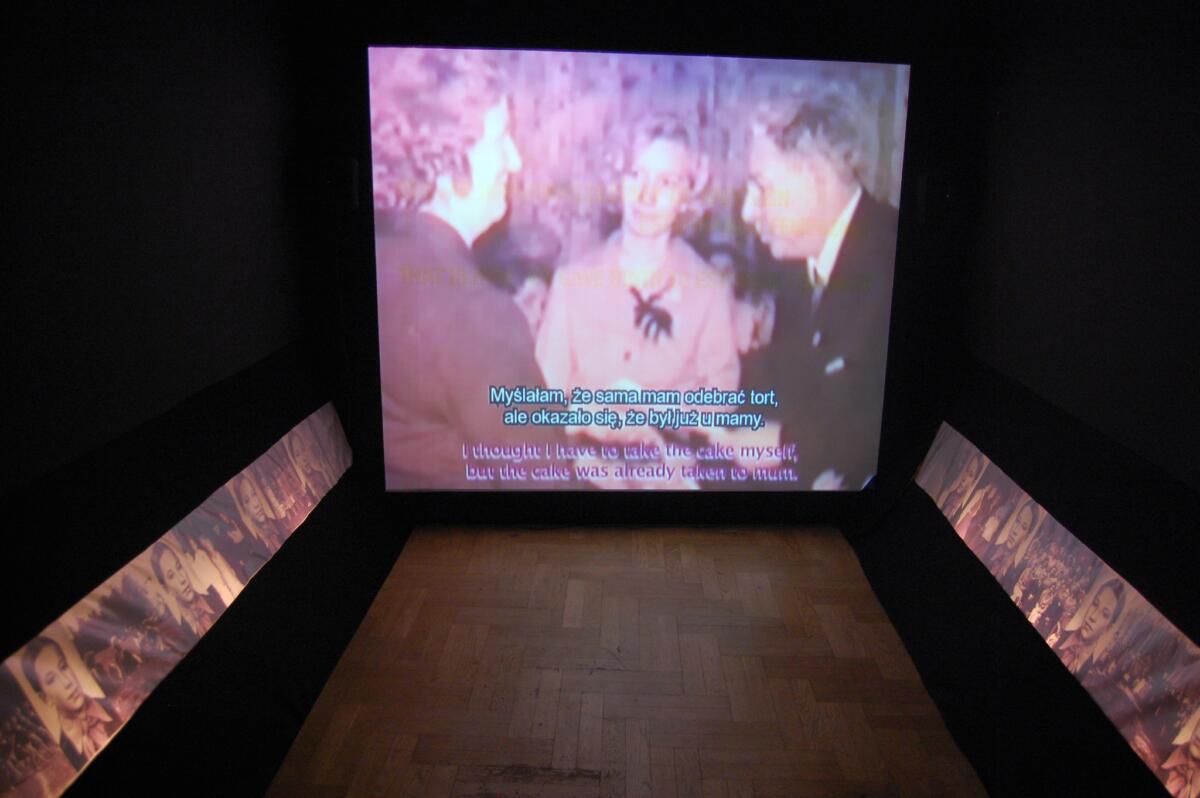

We managed to escape defining the show through a national lens, so there was no such thing as a “Polish corner” or “Estonian corner”. We attempted to present the contemporary art of this part of Eastern Europe in the 90s in a dialogical way. Perhaps it’s not the best word here, but what’s important is that it was not a “comparative” approach. There was no national representation in the exhibition, but individual, artistic representation. After we did the research, we opted for four thematic chapters instead. We didn’t seek artists who were interested in a critique of consumerism or who were approaching sexuality in a particular way. We selected about 120 artworks, which we thought first of all, that were good artworks. I believe they’re all masterpieces. We photographed each piece of art that was to be in the exhibition. And I remember the summer of 1999, I was sitting in the museum library – I didn’t have an office – and I put all the works on the floor and was trying to find a connection between them. And this is how these themes emerged. I named the first chapter “Social Sculpture”, after Joseph Beuys, where the critique of the present was the main focus. The second chapter was “Re-inventing the Past”. The 90s were a period when so many state archives – like the KGB archive in the Soviet Union – became open and there was a trend to deal with these documents. Not only the state ones, but the private, family archives as well started to enter the art discourse. There were wonderful works in this chapter. The third chapter was called “Questioning Subjectivity”. I don’t need to explain the term. And then the fourth – “Gender Scapes”- was the most surprising for me. I was shocked, after traveling and seeing so many catalogs and meeting artists, that so many of them dealt with the issues of femininity and masculinity.

VZ: So how was the exhibition finally perceived by your Eastern European colleagues?

There were some little resistances concerning the following issue. I was born in Serbia and in the 90s, my homeland did start this war in former Yugoslavia. And each knew that I was a Serbian citizen, which was at the moment, a sort of a disturbing factor. I don’t like to talk about it, but then I heard the rumors and then there was the Soros Center annual meeting in Skopje where all the directors and staff of the centers had gathered to discuss what they were going to do, also with the staff from New York and so on. So I was invited to present to them the idea of “After the Wall”. So I started my presentation with a nasty sentence. I said: “Ok, I’m Serbian, but nobody’s perfect”. So this relaxed the situation a little bit.

VZ: Do you think of a definition of Eastern Europe today? When you are talking about “After the Wall”, I understand that the geographical scope of the show was defined by this post-communist condition. But the definition of Eastern Europe changes all the time and sometimes it even seems that it is not relevant anymore. But again, at some point, like now, after the escalation of the Russian war in Ukraine, we immediately realize that indeed, we are living in Eastern Europe. Maybe you have some ideas on how to define this region. What is the common element?

No, I don’t. I cannot give you any definition, but I have an anecdote. When Gorbachev died, the only person from The European Union who went to his funeral was Viktor Orbán. And the BBC commentator said something incredibly interesting: “There was only one representative of Western Europe attending the Gorbachov funeral”.

So, coming back to Eastern Europe as a term, it has its own history. It was different during the Cold War, it’s different now. So I don’t know what this “Eastern European essence” could be. You notice it when you read different authors. You take an anthology about film in Eastern Europe, or socialist and postsocialist Eastern Europe,and there are authors who still defend this term. Then you take another publication which opposes the term Eastern Europe entirely. I also did not have an explanation when working on “Gender Check” or “After the Wall”. I addressed this in the “Gender Check” catalog: do we have the right to still call what we do Eastern European art, Eastern European theory? Who has the right to create Eastern European art? We refuse the Western gaze and so on, but none of us ever knew what that “Eastern European essence” may be. Art history is not a science about truth. It is a field where we discuss conflicting meanings. I like this expression by the writer Salman Rushdie from his wonderful text “Imaginary Homelands”. When he was staying in Great Britain, he thought about his native India and realized that he was reinventing his country, which in fact never existed. Describing the people who are not living in their native country he said: “We are all translated people”. All of us were translated into English. You know, since I came to Berlin, the most important people were not my partners or lovers, but the proofreader, the copy editor, a native speaker. Because through him or her, my voice is heard.

VZ: But you transmit the voice of artists in your writings as well.

I think in a way I’m a victim of art because I see the world around me through an artist’s eyes, you know? And I think this is what we do as art historians. This doesn’t mean that I am telling the truth. For me, the truth in art, regardless of Derrida, are the facts: the medium of the work, dimensions of the work, duration of the video, the title, if the artist gives it, and so on. But we are going to read the artwork with all our burden of literature, the books we read, and try to stay open to what artists want to say at the same time. This is not the truth. Whenever I write an individual essay or text about an artist and I send it to him or her, I’m dying of fear. Did I miss the point? Will the artist accept my interpretation? Some do, some don’t. Mostly they do. And then I was writing a text about Dalibor Martinis. I wrote about his art since the 80s and now he does incredible things. So I wrote to him: “Dalibor, I was dying while you were reading the text”. Then he immediately answered: “Don’t you think that I’m dying of fear when I ask you for the text?” So both sides are taking a risk. This was the first time I was aware of this other perspective. And this was an incredible experience. Now, when I have to summarize, you know, I see that I learned a lot through the process of writing because that’s how some ideas come to you. It’s what I said at the award ceremony: letters and words are our material, but this material is not pregiven, it is shaped through writing or through making exhibitions.

EB: You often mention, also during our interview, your admiration for artists. Can you give us some examples of the contemporary artists that have this courage and dedication you were talking about?

At the moment I’m into Šejla Kamerić. It’s also linked to the history of post-Yugoslavia. She deals with these remnants of the past in the most beautiful way. It really gives some hope, the way that Šejla deals with trauma. Not only national trauma but also her personal trauma; her father was killed at the beginning of the war in Sarajevo. You know, one day this bloody war in Ukraine will be over. This post-war period for artists will also be a traumatic period, because so much death and destruction has happened and there is always a question of how to embed this in an artwork.

EB: You noted that an exhibition is a very important personal learning tool – I suppose both for the audience and the curator. I remember when we were in Ljubljana with Vera in November, we went to the Moderna Gallerija and saw the show “Art at Work”[3], whose main subject was artistic reflection on labor in the art of former Yugoslavia. And I remember us discussing how there is a lot of text in the works themselves, but also on the museum walls. And we agreed that it was a very different way of experiencing an exhibition as compared to what we are used to in Warsaw. I mean, that it’s a learning experience and not only an entertaining one, since many – not all – shows in Warsaw are more object-, not text- or context-oriented. The works from ex-Yugoslavia conveyed a very different understanding of agency.

About the agency of art, I would say there are waves, tendencies. I was formed in the 70s, which was a period of this so-called “post-object art”– new media, video, performance and so on. And I was terribly fond of Dada, particularly Dada in Berlin. In the 70s, our hero was Marcel Duchamp on one end, on the other was Malevich. And we always liked to quote Duchamp. In one interview he said that someone was “stupid as a painter”. He didn’t want to be like this, he had other means to produce his art. The 70s were totally against classical media, painting, sculpture and so on. And in 1975, when members of Art and Language came to Belgrade to do a seminar in our Student Cultural Center gallery we did an exhibition and a publication. After this exhibition I was sure painting as medium is dead. I was hoping that nobody will start to paint again. The 70s were against art market-friendly attitudes.

Then the 80s came and everybody started to paint again. It was the male artist, ego, genius all over again. The 80s were a conservative period with Thatcher, Reagan, and in addition, they were about the market. During that time I didn’t know how to deal with painting, I didn’t know the difference between the many techniques, oil, acrylic and so on. I didn’t know how to relate to these stories which were sometimes intimate stories too, relating to, let’s say, the politics of sexuality and so on. On the other hand, the 90s were a period of curating. In the 90s and the beginning of the 2000s there were so many publications about curating important exhibitions. So if you follow this history, you understand that it changes.

EB: What do you feel the 2020s are or will be about? Certainly this is just speculation, but I’m curious to know if you have an idea, a hunch perhaps? Does something feel different?

I don’t know. It’s a difficult question because, you know, there are so many biennales all around the world. And there are so many curators. I think that this “star curator” figure of the 90s is in recession. You know, there are so many young colleagues. But then there is always this idea of the center, it’s always the peripheries that are busy with this idea. The center is not so interested in peripheries despite the so-called globalization. So this center/periphery dichotomy is still functioning. You know, we are all global, but some of us are more global than others. But I am thinking now of one of Piotr Piotrowski’s ideas, of his concept of “horizontal art history”. And today, unfortunately, this globalization is killing us with the all-encompassing market. But there is still resistance. I would be interested in individual resistances and very personal answers.

VZ: Where do you propose to look for them?

When we were developing the “Gender Check” project – the preparations started in 2007 – Laima Kreivytė[4], who was in charge of Lithuanian art, said something interesting: “When I did my selection, I was interested in the margins”, and this comment stayed in my mind. The margins of national art histories. There are so many artists whose work is still unexplored. You know, the global era is so shockingly aggressive. In the end we also come back to national art histories. And if somebody has a chance again to make a publication or an exhibition to compare these national art histories, this would be my dream for the future. How would such an endeavor look, how would one approach it? In the end it’s a question about when we can meet again.

Edited by Ewa Borysiewicz and Katie Zazenski

[1] “Gender Check. Femininity and Masculinity in the Art of Eastern Europe”, MUMOK, Vienna 2009/2010, Zacheta National Gallery of Art, Warsaw 2010, http://gender-check.erstestiftung.net/

[2] “After the Wall. Art and Culture in Post-Communist Europe”, Moderna Museet, Stockholm, 1999/ 2000, Ludwig Museum, Budapest 2000, Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin 2000, https://www.modernamuseet.se/stockholm/en/exhibitions/after-the-wall/

[3]“Art at Work At the Crossroads Between Utopianism and (In)Dependence”, Museum of Contemporary Art Metelkova (+MSUM), Ljubljana 2022, https://www.mg-lj.si/en/exhibitions/3552/exhibition-art-at-work-at-the-crossroads-between-utopianism-and-independence/

[4]Inteview with Laima Kreivytė on her research in Lithuania: http://gender-check.erstestiftung.net/lithuania-laima-kreivyte/